Byte L10

Entering the uncertain ground of older (often antique in bones) architectural matter to adapt it to contemporary operational demands requires courage and determination. This is especially true when it comes to a seemingly simple, yet always extraordinarily complex genre of housing. To ensure that the outcome of such adaptive efforts does not appear toothless, additional factors are desirable: a cohesive authorial opinion on one hand and trust in it (not blind, but critical) on the other. In the case of a comfortable apartment on one of the pedestrian streets of old Bratislava, fortunately, all the aforementioned conditions met in a favorable intersection. From the synergy between the clear design concept of Bratislavian architect Martin Skoček and the investors' generosity of a young family with two children arose a sympathetic piece of work. A home that primarily delights its owners, but subsequently also the public – whether more specialized or lay – by being able to convey another proof of the right course in the development of contemporary architectural efforts.

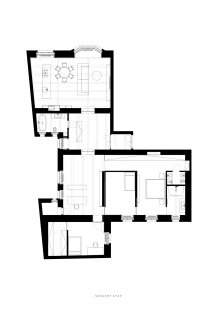

The favorable circumstances of reconstructing the apartment in the Old Town, which this year was developed by architect Martin Skoček, were primarily met by the fact that he could work with two original residential "units". The owners had acquired a smaller and larger apartment in two wings of one floor of a proto-modernist residential building. By merging them, thoughtfully abstracting from archaic typological remnants (such as rooms for servants), and especially by deconstructing senselessly arranged, age-deformed floor plans, he cleared the spatial field for a new arrangement of the dwelling. He follows the proven logic of room arrangement and current strategies of the residential genre. With a clean cut of communication, the architect separated the living zone facing the street from the private "suite" part with a bedroom, two children's rooms, and a nook for a study/game room with views into the courtyard. Both halves are essentially "single-space" halls, which the architect skillfully articulated with built-in furniture components. In the case of the private zone, the rectangular hall area is further complemented by one separate teenage room.

A semi-public hallway lined with a strict row of oak cabinets hanging on the wall leads into the entrance vestibule of the apartment. Its carefully arranged "scenography" hints at the overall mood of the rest. In it, a sincere first-republican "school of nobility" meets contemporary opinions. The intimate entrance vestibule opens into the central hall that connects both halves of the apartment. The architect stripped it down in an expression of formal restraint. He had the concrete ribs of the ceiling cleaned and the beautifully delineated shallow arches restored, had the oak flooring and the historic double-leaf doors restored, and highlighted their charismatic charm against the backdrop of bright white walls. To prevent the result from being burdened by the necessary wardrobe cabinet, he installed a "disembodied" version of it directly in the middle of the hall: a box wrapped in mirrors. In this ethereal expression, the cabinet literally disappears from sight. At the same time, it articulates the forefront of the bathroom and the side niche with a replica of wooden paneling.

"Archaeological" methods of revealing original building structures continue in other parts of the apartment. The concrete ceiling defines the living part of the private zone, that is, the place for the game room, study, and library. In the living room, the ceiling area belongs to a wooden beam ceiling with steel girders. Its soft expression finds a counterpart in the mentioned oak floor; together with the surrounding snow-white walls, they delineate a modest yet practically furnished living space. In the light pouring in from the bay window, the simply arranged layout stands out. The living room with spacious seating is followed by the dining zone and finally, at the very end, the kitchen. It is designed as a simple block of stainless steel island and a side assembly of cabinets, partially embedded in the depth of the walls to accommodate necessary kitchen appliances as well as an exhibition showcase for the sideboard. Because the kitchen lacks a "backstage" – instead, it is just a blank wall with a dominant canvas by painter Ivan Csudai – it seamlessly blends into the relaxed living atmosphere of the room. The straightforward situation is thus outlined by just a handful of elements, yet it still conveys a friendly "lived-in" impression.

Martin Skoček applied a bolder spatial concept in the sleeping quarters. The space is divided by sliding doors, enabling the individual rooms to blend into a homogeneous whole. Instead of oak panels, a white woolen carpet serves as an unifying element here. It gives the rooms a pliable touch, softening the concrete ceiling. White plaster walls, smoothed to nearly "jeweler's" quality in craft virtuosity, also play an important role here. The material palette is further complemented by oak veneers in the built-in furniture, neutral textiles, and colorful terrazzo on the bathroom floor; together they form the final expression of modest peace.

Behind the seemingly simple interior solution limited to just a few ingredients lies a demanding realization drama. The architect knows very well that the devil is in the details. That is why he took great care, almost fundamentally, in thoughtful little things that require precision in execution. Thanks to these, he built an apartment where detailed interest penetrates down to the smallest atoms and, in this "strong interaction", holds together the authenticity of a truly honest work.

The favorable circumstances of reconstructing the apartment in the Old Town, which this year was developed by architect Martin Skoček, were primarily met by the fact that he could work with two original residential "units". The owners had acquired a smaller and larger apartment in two wings of one floor of a proto-modernist residential building. By merging them, thoughtfully abstracting from archaic typological remnants (such as rooms for servants), and especially by deconstructing senselessly arranged, age-deformed floor plans, he cleared the spatial field for a new arrangement of the dwelling. He follows the proven logic of room arrangement and current strategies of the residential genre. With a clean cut of communication, the architect separated the living zone facing the street from the private "suite" part with a bedroom, two children's rooms, and a nook for a study/game room with views into the courtyard. Both halves are essentially "single-space" halls, which the architect skillfully articulated with built-in furniture components. In the case of the private zone, the rectangular hall area is further complemented by one separate teenage room.

A semi-public hallway lined with a strict row of oak cabinets hanging on the wall leads into the entrance vestibule of the apartment. Its carefully arranged "scenography" hints at the overall mood of the rest. In it, a sincere first-republican "school of nobility" meets contemporary opinions. The intimate entrance vestibule opens into the central hall that connects both halves of the apartment. The architect stripped it down in an expression of formal restraint. He had the concrete ribs of the ceiling cleaned and the beautifully delineated shallow arches restored, had the oak flooring and the historic double-leaf doors restored, and highlighted their charismatic charm against the backdrop of bright white walls. To prevent the result from being burdened by the necessary wardrobe cabinet, he installed a "disembodied" version of it directly in the middle of the hall: a box wrapped in mirrors. In this ethereal expression, the cabinet literally disappears from sight. At the same time, it articulates the forefront of the bathroom and the side niche with a replica of wooden paneling.

"Archaeological" methods of revealing original building structures continue in other parts of the apartment. The concrete ceiling defines the living part of the private zone, that is, the place for the game room, study, and library. In the living room, the ceiling area belongs to a wooden beam ceiling with steel girders. Its soft expression finds a counterpart in the mentioned oak floor; together with the surrounding snow-white walls, they delineate a modest yet practically furnished living space. In the light pouring in from the bay window, the simply arranged layout stands out. The living room with spacious seating is followed by the dining zone and finally, at the very end, the kitchen. It is designed as a simple block of stainless steel island and a side assembly of cabinets, partially embedded in the depth of the walls to accommodate necessary kitchen appliances as well as an exhibition showcase for the sideboard. Because the kitchen lacks a "backstage" – instead, it is just a blank wall with a dominant canvas by painter Ivan Csudai – it seamlessly blends into the relaxed living atmosphere of the room. The straightforward situation is thus outlined by just a handful of elements, yet it still conveys a friendly "lived-in" impression.

Martin Skoček applied a bolder spatial concept in the sleeping quarters. The space is divided by sliding doors, enabling the individual rooms to blend into a homogeneous whole. Instead of oak panels, a white woolen carpet serves as an unifying element here. It gives the rooms a pliable touch, softening the concrete ceiling. White plaster walls, smoothed to nearly "jeweler's" quality in craft virtuosity, also play an important role here. The material palette is further complemented by oak veneers in the built-in furniture, neutral textiles, and colorful terrazzo on the bathroom floor; together they form the final expression of modest peace.

Behind the seemingly simple interior solution limited to just a few ingredients lies a demanding realization drama. The architect knows very well that the devil is in the details. That is why he took great care, almost fundamentally, in thoughtful little things that require precision in execution. Thanks to these, he built an apartment where detailed interest penetrates down to the smallest atoms and, in this "strong interaction", holds together the authenticity of a truly honest work.

Michal Lalinský

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment