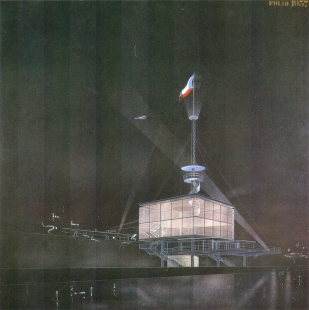

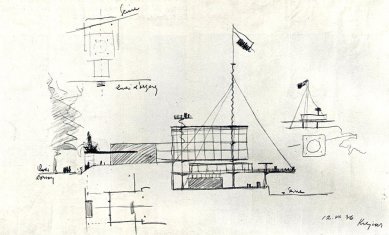

Czechoslovak Pavilion at the International Exhibition of Arts and Techniques in Modern Life

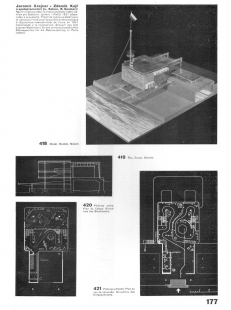

Accompanying report for the project by architect Jaromír Krejcar and collaborators (architect Z. Kejře, Professor L. Sutnara, B. Soumara).

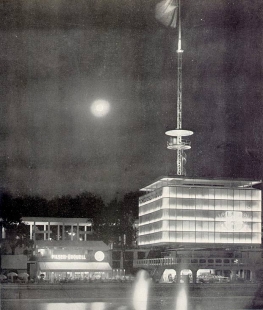

In the architecture of the pavilion, the designers were guided by the idea that while strictly adhering to the requirements of modern Czechoslovak architecture, the pavilion should represent Czechoslovakia in Paris in a way that satisfies international taste, yearning for a softer form than is usually found in our country. This effect was partly achieved by the division of surfaces and the rounding of edges, without breaking the impression of architectural coherence of the exhibition pavilion. Fragmentation of space inside is a necessary variation, not a program. The exhibition spaces should be as large as possible, though not monotonous. The visitor must enter a space where they can take a break from the intimate installations that had to be created for the overall impression and for enclosing the areas for a specific exhibition. Observing the development of world exhibitions in the post-war period, we find that glass is increasingly being used as the façade of modern pavilions. For example, last year's Brussels exhibition only confirms this assertion. The modern architect's desire is to bring as much daylight into the exhibition pavilion as possible, and it is much more advantageous to soften the light obtained this way and achieve intimacy than to construct a dark pavilion and illuminate it artificially.

Full walls are used in pavilions mostly by department stores, which normally utilize solid walls for advertising purposes, but this is not the aim of the state pavilions' architecture. Only Oriental and Southern nations build solid pavilions as a showcase of their old historical southern culture. Last year in Brussels, France had a pavilion with opaque walls. However, the pavilion measured about 12,000 m². Therefore, it was a necessity to use lighting from the ceiling. Italy used opaque walls only for the large state pavilion and in the reproduction of the old Roman pavilion; otherwise, special pavilions were almost all glass. Pavilions where more than half of the façade was made of glass included those from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, Austria, Finland, and Lithuania, thus pavilions that were architecturally the most pleasing, pavilions of countries considered the most progressive in exhibitions.

Most of the exhibited items in the pavilion do not require any special intimacy; on the contrary, excessive intimacy often has a suffocating effect on the audience in the exhibition and can only be used in certain exhibition sections. This was addressed by the use of Heraklit, and then by the use of Thermolux, a truly ideal façade glass that absorbs 80% of thermal rays. Perhaps only because ordinary glass has so far been a good conductor of heat were materials like this not used at exhibitions as much as all exhibitors would wish. Everyone desires to achieve vertical daylight lighting for exhibition spaces. Thermolux provides the exhibition spaces with light in such a way that the audience is concentrated on viewing the exhibited items with very good lighting. The use of this material (Thermolux) certainly has a great future, especially in exhibitions.

As we progress through the exhibition spaces of the pavilion, we observe that only the glass and jewelery sections require artificial lighting, as do the cinema, theater models, and partially tourist traffic (dioramas, etc.).

This requirement was fully met. Semi-intimacy for textiles, total fashion, and modern living is achieved with lighter or heavier fabrics like curtains, which are also suitable exhibition goods. Other spaces, for example, the heavy industry hall, the exhibition of the social structure of the state, urbanism, etc., require good lighting, although subdued in nature by Thermolux, but still quite lively lighting.

Use of construction materials.

In selecting construction materials, attention was paid to meet the interests of the Czechoslovak export industry as much as possible. It is almost a necessity that we use our materials that can be exported for the exhibition pavilion. The exhibition is not made solely for France, but for the entire educated world, and experience teaches that especially the visits of rare foreigners at exhibitions have brought much benefit to our industrial promotion in any direction. By using a combination of steel and Thermolux, we arrive at the exhibition with new, groundbreaking materials that are technically very advanced. This combination would highlight the new great possibilities in the selection of modern materials. The steel structure, executed by Vítkovické železárny, is also a good promotional Czechoslovak material. The basic materials include flooring from Slovak marbles, or other flooring materials, especially ceramic and glass, and the use of Zlinolith. By using construction materials capable of export, there is a possibility that for advertising purposes, companies would provide these materials more cheaply than at normal market prices, and would consider the used construction materials as their own exhibition.

In solving the façade and all spaces of the pavilion, influence has to be exerted on the psychology of the exhibition audience. The psychology of visitors to world exhibitions is quite different from that of visitors to smaller and special exhibitions held in certain museums, etc. It can be said that 90% of people, who are neither exhibition professionals nor have higher cultural demands, dedicate a very limited time to viewing exhibition pavilions. Even if, for instance, a Parisian comes to the exhibition ten or twenty times, they always scan only a small section of the exhibition pavilions quickly and spend the rest of their time on entertainment and pleasant observations. Therefore, the content of the pavilion should be such that it captivates the masses of these normal visitors while also satisfying the demands of the culturally advanced visitor.

Visiting the pavilion.

The aim of the designers was to arrange the pavilion so that its interesting architecture and entrance would invite the visitor inside. The entrance hall should invite further exploration of the pavilion through its views, and the end of the pavilion should leave a favorable impression on the visitor with the interesting solution of the "Prague street" — the tourist traffic section. It is the endeavor of every exhibitor to first attract the visitor into the pavilion, then ensure that the visitor is satisfied with the content of the pavilion, and above all that the last impression when exiting the pavilion is positive and vivid.

Opinions have often been expressed that pathways should guide the visitor so that they do not miss any exhibition space, nor are led into the exhibition space twice. In doing so, attention should be paid to ensuring that, as far as possible, the more important exhibition areas are installed on one side only so that the visitor does not overlook more important exhibited items. This corresponds more to the needs of special exhibitions, where the attendance is too small, so that normally if the visitor remains on the left side of the pathway, they are only shown exhibitions that remain on their left-hand side. At the World Exhibition in Chicago, where the Czechoslovak pavilion was so suitably placed as it will be at the World Exhibition in Paris, the pavilion was visited by 6.5 million people. It was the first exhibition where attendance in individual pavilions was also counted. The Colonial Exhibition in Paris in 1931 had 27 million visitors. The exhibition next year, which is in the middle of Paris, could very easily have 30 million visitors. Of these, 8 million visitors could visit the Czechoslovak pavilion. Thus, the average daily attendance could be 50,000 people, which means that there will continuously be a great flow of visitors in the Czechoslovak pavilion as at other exhibitions.

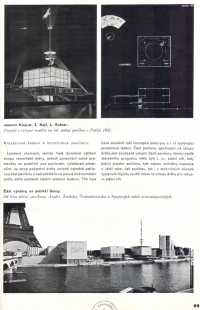

At the International Exhibition of Art and Technology in Modern Life

Jaromír Krejcar: Czechoslovak State Pavilion in Paris 1937

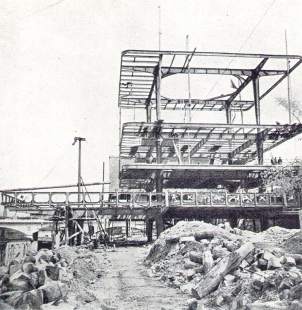

Construction site of the pavilion.

There has already been much discussion about the suitability or unsuitability of the site selected by the Ministry of Public Works for the Czechoslovak pavilion. Proponents of the view that the exhibition pavilion needs to be no more than an as cheaply acquired shelter for the exhibited items — which is itself completely unimportant — found the site completely inadequate. They pointed out that the site has significant height differences and requires complex technical solutions for construction. According to them, the only suitable place for the exhibition pavilion would be a completely flat area without height differences.

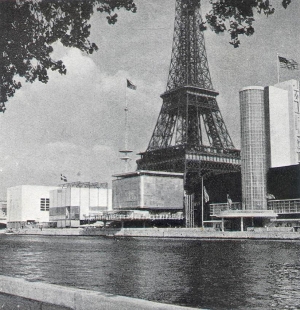

Today, when the exhibition is completed and we have the opportunity to practically compare the internal layouts and external impressions of the pavilions built on flat ground — and pavilions for which height differences in the terrain were overcome, we see that it is precisely by utilizing these differences that the layouts of the most interesting pavilions at the exhibition, such as those of Japan, Switzerland, Sweden, and the Netherlands, were created.

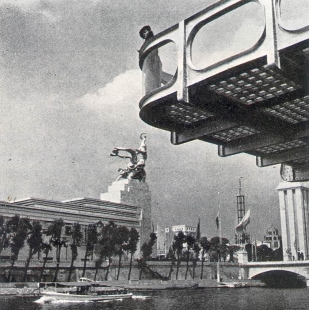

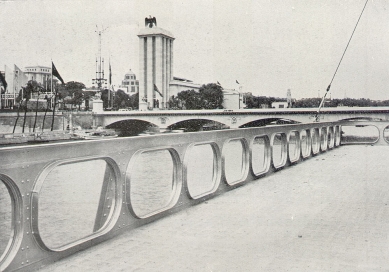

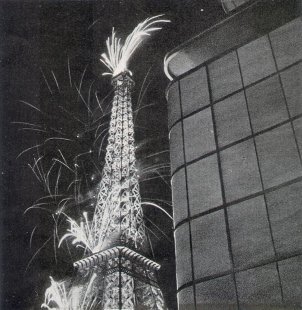

The site of the Czechoslovak pavilion — maximally expressed — actually does not have a fully usable area. It is a certain defined cubus in space, resting approximately one third on a very lightly loadable ceiling of the underground railway (1100 kg/m²) and the rest is placed above the waterfront promenade, which must remain free. Therefore, from the perspective of so-called exhibition practitioners, this is certainly a terrible case when they realized that we have a site on which it is practically forbidden to build. From a technical standpoint, however, it is a beautiful task to overcome the given difficulties and utilize them for the internal and external solutions of the building. Considering the entire exhibition, it is noteworthy that the spots on the left bank of the Seine, where the Czechoslovak pavilion also stands, are among the most beautiful and exhibitionally advantageous. The pavilions are placed here between two main exhibition promenades, the waterfront Quai d'Orsay and the riverside promenade along the Seine. In an overview image of the right side of the exhibition from the Jena Bridge (the main axis of the exhibition), starting from the bridge, the pavilions are: English, Swedish, Czechoslovak, and the United States of America. The second half of the waterfront promenade under the Eiffel Tower, roughly symmetrical to the Jena Bridge, is occupied by the pavilions: Belgian, Swiss, and Italian.

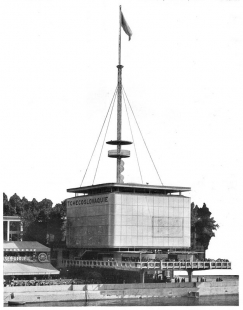

Spatial solution and construction of the pavilion.

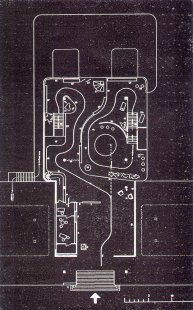

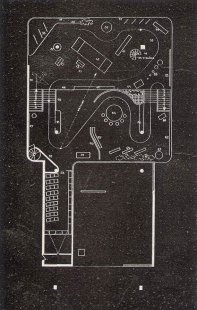

The mentioned circumstances, both the small allowed load on the ceiling of the Versailles railway and the retention of a free promenade on the riverside under the pavilion, primarily required: to place the least loaded part of the pavilion on the ceiling of the railway and to build the actual exhibition building above the waterfront on as few pillars as possible. This fundamentally determined the entire concept of the floor plan and the resulting spatial solution. The part of the pavilion resting on the railway ceiling is simultaneously the entrance portion of the pavilion, which, according to the construction program, was to be the so-called state hall, thus the only space in the pavilion where heavier exhibitions are not placed. Both by location and for technical reasons, the logical use of the place on the railway ceiling for the entrance state hall came about.

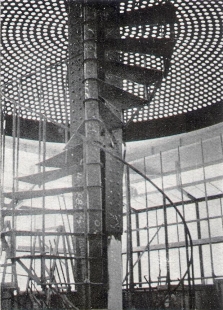

Because a load allowance of 650 kg/m² was required for the actual exhibition building resting on pillars above the waterfront promenade due to the significant weight of the exhibited items, it was advantageous to use a steel skeleton for its construction. The benefits of the steel skeleton constructed by Vítkovické železárny (Dr. Ing. Wagner, Dr. Ing. Klír, Ing. Förster) were maximally utilized here. The three-story exhibition building with a square floor plan of 20.5 m x 25.5 m and a height of 20 m rests on four columns spaced 12.10 m apart. The cantilever overhangs 4.20 m. The terrace over the Seine is cantilevered 6.5 m.

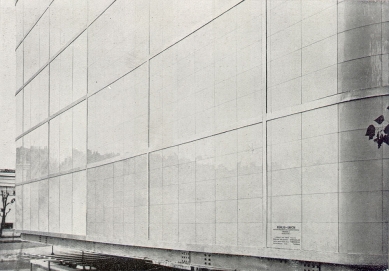

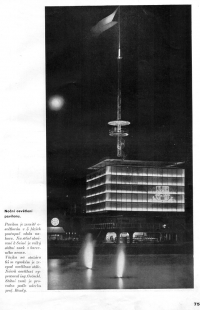

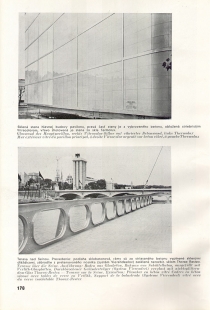

The walls of the pavilion were made exclusively of glass. The walls of the main exhibition building are entirely of Thermolux glass, the walls of the state hall are made of hollow glass bricks, and the ceiling is composed of Thermolux panels.

The ceilings of the pavilion are dry-assembled from 6 cm thick Hourdis plates of French manufacture. (During a load test, a plate of size 60 cm/100 cm deflected by 3 cm under a load of 2000 kg!)

Approximately 30,000 kg of steel was used for the steel frame, about 1100 m² of Thermolux glass for the walls and ceilings, and about 200 m² of hollow glass bricks.

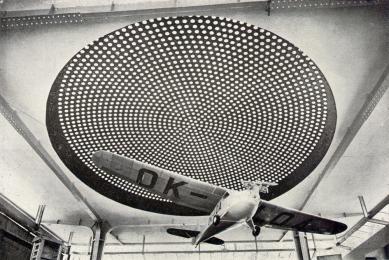

The ceiling of the industrial hall on the first floor of the pavilion is glazed with a glass-concrete dome with a diameter of 12 m and a constructive height of 1.5 m.

Architecture of the pavilion.

Utility here is a multifaceted concept. Naturally, as with any construction, it is primarily about achieving perfect functionality for a specific purpose, in this case, for exhibition purposes. It is true that through the intensification of purely functional demands for the given purpose (the freest possible space), I arrived at a minimum of four constructive supports, but consistently, I pursued the goal of demonstrating the manufacturing capabilities of Czechoslovak industry; for example, with the rounded corner panels made of Thermolux glass, which in the dimensions used in the Czechoslovak pavilion are produced for the first time in the world. There is no doubt that square corners would have been equally functional as rounded ones, just as smaller glass panels would have sufficed.

Therefore, it was not just about function in regard to the perfect operation of exhibiting various products inside the building — but also about fulfilling that exceptional function of the Czechoslovak pavilion building in the midst of the World Exhibition. This purpose eliminates otherwise one of the most important components of contemporary architecture — the component of technical and economic efficiency. Likewise, there is no doubt that for the perfect lighting of the state hall, a glass ceiling would have sufficed — and the walls could have been made of Heraklit panels. But again, the purpose was not only to achieve a well-lit hall space but to apply, on an unusually large scale, the use of our special glass product, hollow glass insulating bricks. (Incidentally, during the construction of the pavilion, America made a significant order for this material.)

The architecture of the pavilion emerged from the demand to demonstrate not only the perfection and advancement of Czechoslovak glass and steel industries through its construction, but also its greatest technical possibilities.

Interiors.

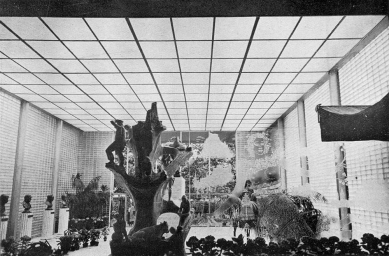

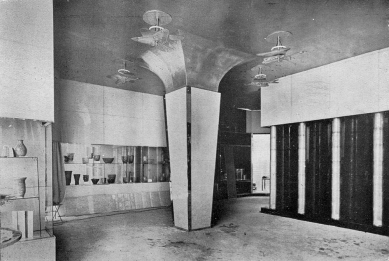

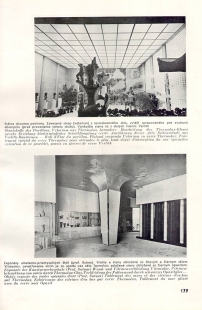

The internal solution of the pavilion is in complete contradiction to its spatial concept and construction. Why was it designed this way? — It was not designed — it arose. It arose from the fact that our exhibitors or their representatives do not yet comprehend that a state exhibition as a coherent whole would mean much more for individual fields than a series of small rooms into which the internal space of the pavilion is fragmented. Therefore, compared to the Swiss, Swedish, Japanese, and English pavilions, which appear unified in a large space where the state and its products are simply presented, the interior of the Czechoslovak pavilion creates a fair-like impression. The debates over m² of exhibition space are immediately noticeable here. Likewise, it is an incomprehensible matter for most visitors that inside a pavilion that is entirely made of glass, artificial lighting is necessary. The authors of the glass and porcelain exhibition were convinced that neither glass nor porcelain could be exhibited in natural light. Therefore, the rooms where glass and porcelain are on display were artificially darkened and are artificially lit. This is detrimental to the exhibitions, as evidenced by the fact that in the Swedish pavilion it is clearly shown how splendidly glass exhibitions can operate in natural light.

Another striking feature of the exhibitions in the Czechoslovak pavilion is at first glance the apparent fear that someone might steal something. Thus, all items are behind glass. In the other pavilions, such as the English, Swedish, Swiss, etc., it is quietly possible to touch the items. Our textiles hidden behind glass before the visitors' hands feel somewhat awkward. Elsewhere, textiles are touched, examined in detail, while here visitors pass by indifferently. The only somewhat cohesive space was maintained in the so-called industrial hall, where daylight was saved only by the glass-concrete dome, otherwise it would similarly have been necessary to illuminate there — because the glass walls are built all around inside to full height.

It is rumored that the exhibition will be extended into next year. Over the winter (December, January, February), it would be closed. If the extension of the exhibition is realized, then certainly the states that participate in the extended exhibition will make some new adjustments to their exhibitions.

I would recommend that the internal arrangement of the Czechoslovak pavilion be fundamentally changed, that a new unified plan for the adjustment of all exhibitions be developed, which would truly utilize the exhibition possibilities that the all-glass pavilion provides. We can find lessons on how to modernly install exhibitions in the Swiss, Swedish, English, Japanese pavilions, etc.

But primarily, the pavilion should be installed from a national perspective, subordinating the interests of various companies to the whole so that our industrial products imprint in the memory of visitors as — made in Czechoslovakia.

Others are capable of doing this too; we know Swedish steel, Japanese porcelain, English textiles, Swiss clocks, etc. Do we know the manufacturers? No. The name of the country is sufficient.

In the architecture of the pavilion, the designers were guided by the idea that while strictly adhering to the requirements of modern Czechoslovak architecture, the pavilion should represent Czechoslovakia in Paris in a way that satisfies international taste, yearning for a softer form than is usually found in our country. This effect was partly achieved by the division of surfaces and the rounding of edges, without breaking the impression of architectural coherence of the exhibition pavilion. Fragmentation of space inside is a necessary variation, not a program. The exhibition spaces should be as large as possible, though not monotonous. The visitor must enter a space where they can take a break from the intimate installations that had to be created for the overall impression and for enclosing the areas for a specific exhibition. Observing the development of world exhibitions in the post-war period, we find that glass is increasingly being used as the façade of modern pavilions. For example, last year's Brussels exhibition only confirms this assertion. The modern architect's desire is to bring as much daylight into the exhibition pavilion as possible, and it is much more advantageous to soften the light obtained this way and achieve intimacy than to construct a dark pavilion and illuminate it artificially.

Full walls are used in pavilions mostly by department stores, which normally utilize solid walls for advertising purposes, but this is not the aim of the state pavilions' architecture. Only Oriental and Southern nations build solid pavilions as a showcase of their old historical southern culture. Last year in Brussels, France had a pavilion with opaque walls. However, the pavilion measured about 12,000 m². Therefore, it was a necessity to use lighting from the ceiling. Italy used opaque walls only for the large state pavilion and in the reproduction of the old Roman pavilion; otherwise, special pavilions were almost all glass. Pavilions where more than half of the façade was made of glass included those from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, Austria, Finland, and Lithuania, thus pavilions that were architecturally the most pleasing, pavilions of countries considered the most progressive in exhibitions.

Most of the exhibited items in the pavilion do not require any special intimacy; on the contrary, excessive intimacy often has a suffocating effect on the audience in the exhibition and can only be used in certain exhibition sections. This was addressed by the use of Heraklit, and then by the use of Thermolux, a truly ideal façade glass that absorbs 80% of thermal rays. Perhaps only because ordinary glass has so far been a good conductor of heat were materials like this not used at exhibitions as much as all exhibitors would wish. Everyone desires to achieve vertical daylight lighting for exhibition spaces. Thermolux provides the exhibition spaces with light in such a way that the audience is concentrated on viewing the exhibited items with very good lighting. The use of this material (Thermolux) certainly has a great future, especially in exhibitions.

As we progress through the exhibition spaces of the pavilion, we observe that only the glass and jewelery sections require artificial lighting, as do the cinema, theater models, and partially tourist traffic (dioramas, etc.).

This requirement was fully met. Semi-intimacy for textiles, total fashion, and modern living is achieved with lighter or heavier fabrics like curtains, which are also suitable exhibition goods. Other spaces, for example, the heavy industry hall, the exhibition of the social structure of the state, urbanism, etc., require good lighting, although subdued in nature by Thermolux, but still quite lively lighting.

Use of construction materials.

In selecting construction materials, attention was paid to meet the interests of the Czechoslovak export industry as much as possible. It is almost a necessity that we use our materials that can be exported for the exhibition pavilion. The exhibition is not made solely for France, but for the entire educated world, and experience teaches that especially the visits of rare foreigners at exhibitions have brought much benefit to our industrial promotion in any direction. By using a combination of steel and Thermolux, we arrive at the exhibition with new, groundbreaking materials that are technically very advanced. This combination would highlight the new great possibilities in the selection of modern materials. The steel structure, executed by Vítkovické železárny, is also a good promotional Czechoslovak material. The basic materials include flooring from Slovak marbles, or other flooring materials, especially ceramic and glass, and the use of Zlinolith. By using construction materials capable of export, there is a possibility that for advertising purposes, companies would provide these materials more cheaply than at normal market prices, and would consider the used construction materials as their own exhibition.

In solving the façade and all spaces of the pavilion, influence has to be exerted on the psychology of the exhibition audience. The psychology of visitors to world exhibitions is quite different from that of visitors to smaller and special exhibitions held in certain museums, etc. It can be said that 90% of people, who are neither exhibition professionals nor have higher cultural demands, dedicate a very limited time to viewing exhibition pavilions. Even if, for instance, a Parisian comes to the exhibition ten or twenty times, they always scan only a small section of the exhibition pavilions quickly and spend the rest of their time on entertainment and pleasant observations. Therefore, the content of the pavilion should be such that it captivates the masses of these normal visitors while also satisfying the demands of the culturally advanced visitor.

Visiting the pavilion.

The aim of the designers was to arrange the pavilion so that its interesting architecture and entrance would invite the visitor inside. The entrance hall should invite further exploration of the pavilion through its views, and the end of the pavilion should leave a favorable impression on the visitor with the interesting solution of the "Prague street" — the tourist traffic section. It is the endeavor of every exhibitor to first attract the visitor into the pavilion, then ensure that the visitor is satisfied with the content of the pavilion, and above all that the last impression when exiting the pavilion is positive and vivid.

Opinions have often been expressed that pathways should guide the visitor so that they do not miss any exhibition space, nor are led into the exhibition space twice. In doing so, attention should be paid to ensuring that, as far as possible, the more important exhibition areas are installed on one side only so that the visitor does not overlook more important exhibited items. This corresponds more to the needs of special exhibitions, where the attendance is too small, so that normally if the visitor remains on the left side of the pathway, they are only shown exhibitions that remain on their left-hand side. At the World Exhibition in Chicago, where the Czechoslovak pavilion was so suitably placed as it will be at the World Exhibition in Paris, the pavilion was visited by 6.5 million people. It was the first exhibition where attendance in individual pavilions was also counted. The Colonial Exhibition in Paris in 1931 had 27 million visitors. The exhibition next year, which is in the middle of Paris, could very easily have 30 million visitors. Of these, 8 million visitors could visit the Czechoslovak pavilion. Thus, the average daily attendance could be 50,000 people, which means that there will continuously be a great flow of visitors in the Czechoslovak pavilion as at other exhibitions.

Stavba XIII, 1936-1937, s. 175-176.

At the International Exhibition of Art and Technology in Modern Life

Jaromír Krejcar: Czechoslovak State Pavilion in Paris 1937

Construction site of the pavilion.

There has already been much discussion about the suitability or unsuitability of the site selected by the Ministry of Public Works for the Czechoslovak pavilion. Proponents of the view that the exhibition pavilion needs to be no more than an as cheaply acquired shelter for the exhibited items — which is itself completely unimportant — found the site completely inadequate. They pointed out that the site has significant height differences and requires complex technical solutions for construction. According to them, the only suitable place for the exhibition pavilion would be a completely flat area without height differences.

Today, when the exhibition is completed and we have the opportunity to practically compare the internal layouts and external impressions of the pavilions built on flat ground — and pavilions for which height differences in the terrain were overcome, we see that it is precisely by utilizing these differences that the layouts of the most interesting pavilions at the exhibition, such as those of Japan, Switzerland, Sweden, and the Netherlands, were created.

The site of the Czechoslovak pavilion — maximally expressed — actually does not have a fully usable area. It is a certain defined cubus in space, resting approximately one third on a very lightly loadable ceiling of the underground railway (1100 kg/m²) and the rest is placed above the waterfront promenade, which must remain free. Therefore, from the perspective of so-called exhibition practitioners, this is certainly a terrible case when they realized that we have a site on which it is practically forbidden to build. From a technical standpoint, however, it is a beautiful task to overcome the given difficulties and utilize them for the internal and external solutions of the building. Considering the entire exhibition, it is noteworthy that the spots on the left bank of the Seine, where the Czechoslovak pavilion also stands, are among the most beautiful and exhibitionally advantageous. The pavilions are placed here between two main exhibition promenades, the waterfront Quai d'Orsay and the riverside promenade along the Seine. In an overview image of the right side of the exhibition from the Jena Bridge (the main axis of the exhibition), starting from the bridge, the pavilions are: English, Swedish, Czechoslovak, and the United States of America. The second half of the waterfront promenade under the Eiffel Tower, roughly symmetrical to the Jena Bridge, is occupied by the pavilions: Belgian, Swiss, and Italian.

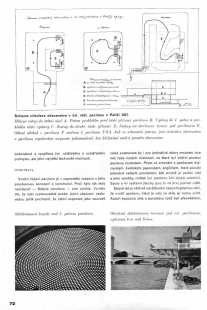

Spatial solution and construction of the pavilion.

The mentioned circumstances, both the small allowed load on the ceiling of the Versailles railway and the retention of a free promenade on the riverside under the pavilion, primarily required: to place the least loaded part of the pavilion on the ceiling of the railway and to build the actual exhibition building above the waterfront on as few pillars as possible. This fundamentally determined the entire concept of the floor plan and the resulting spatial solution. The part of the pavilion resting on the railway ceiling is simultaneously the entrance portion of the pavilion, which, according to the construction program, was to be the so-called state hall, thus the only space in the pavilion where heavier exhibitions are not placed. Both by location and for technical reasons, the logical use of the place on the railway ceiling for the entrance state hall came about.

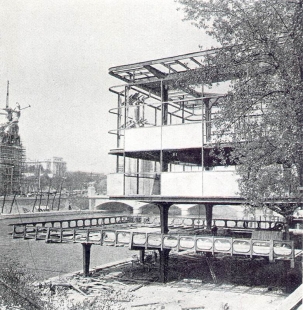

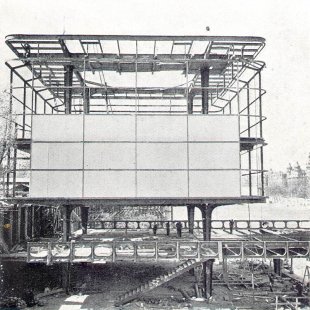

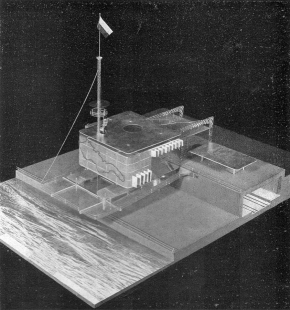

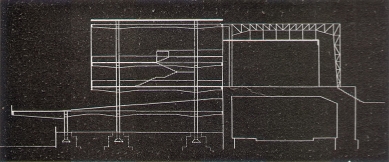

Because a load allowance of 650 kg/m² was required for the actual exhibition building resting on pillars above the waterfront promenade due to the significant weight of the exhibited items, it was advantageous to use a steel skeleton for its construction. The benefits of the steel skeleton constructed by Vítkovické železárny (Dr. Ing. Wagner, Dr. Ing. Klír, Ing. Förster) were maximally utilized here. The three-story exhibition building with a square floor plan of 20.5 m x 25.5 m and a height of 20 m rests on four columns spaced 12.10 m apart. The cantilever overhangs 4.20 m. The terrace over the Seine is cantilevered 6.5 m.

The walls of the pavilion were made exclusively of glass. The walls of the main exhibition building are entirely of Thermolux glass, the walls of the state hall are made of hollow glass bricks, and the ceiling is composed of Thermolux panels.

The ceilings of the pavilion are dry-assembled from 6 cm thick Hourdis plates of French manufacture. (During a load test, a plate of size 60 cm/100 cm deflected by 3 cm under a load of 2000 kg!)

Approximately 30,000 kg of steel was used for the steel frame, about 1100 m² of Thermolux glass for the walls and ceilings, and about 200 m² of hollow glass bricks.

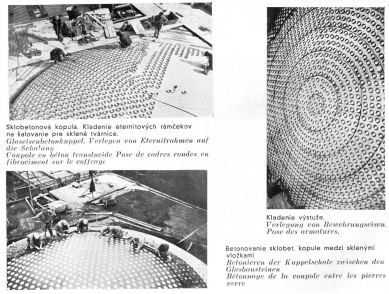

The ceiling of the industrial hall on the first floor of the pavilion is glazed with a glass-concrete dome with a diameter of 12 m and a constructive height of 1.5 m.

Architecture of the pavilion.

Utility here is a multifaceted concept. Naturally, as with any construction, it is primarily about achieving perfect functionality for a specific purpose, in this case, for exhibition purposes. It is true that through the intensification of purely functional demands for the given purpose (the freest possible space), I arrived at a minimum of four constructive supports, but consistently, I pursued the goal of demonstrating the manufacturing capabilities of Czechoslovak industry; for example, with the rounded corner panels made of Thermolux glass, which in the dimensions used in the Czechoslovak pavilion are produced for the first time in the world. There is no doubt that square corners would have been equally functional as rounded ones, just as smaller glass panels would have sufficed.

Therefore, it was not just about function in regard to the perfect operation of exhibiting various products inside the building — but also about fulfilling that exceptional function of the Czechoslovak pavilion building in the midst of the World Exhibition. This purpose eliminates otherwise one of the most important components of contemporary architecture — the component of technical and economic efficiency. Likewise, there is no doubt that for the perfect lighting of the state hall, a glass ceiling would have sufficed — and the walls could have been made of Heraklit panels. But again, the purpose was not only to achieve a well-lit hall space but to apply, on an unusually large scale, the use of our special glass product, hollow glass insulating bricks. (Incidentally, during the construction of the pavilion, America made a significant order for this material.)

The architecture of the pavilion emerged from the demand to demonstrate not only the perfection and advancement of Czechoslovak glass and steel industries through its construction, but also its greatest technical possibilities.

Interiors.

The internal solution of the pavilion is in complete contradiction to its spatial concept and construction. Why was it designed this way? — It was not designed — it arose. It arose from the fact that our exhibitors or their representatives do not yet comprehend that a state exhibition as a coherent whole would mean much more for individual fields than a series of small rooms into which the internal space of the pavilion is fragmented. Therefore, compared to the Swiss, Swedish, Japanese, and English pavilions, which appear unified in a large space where the state and its products are simply presented, the interior of the Czechoslovak pavilion creates a fair-like impression. The debates over m² of exhibition space are immediately noticeable here. Likewise, it is an incomprehensible matter for most visitors that inside a pavilion that is entirely made of glass, artificial lighting is necessary. The authors of the glass and porcelain exhibition were convinced that neither glass nor porcelain could be exhibited in natural light. Therefore, the rooms where glass and porcelain are on display were artificially darkened and are artificially lit. This is detrimental to the exhibitions, as evidenced by the fact that in the Swedish pavilion it is clearly shown how splendidly glass exhibitions can operate in natural light.

Another striking feature of the exhibitions in the Czechoslovak pavilion is at first glance the apparent fear that someone might steal something. Thus, all items are behind glass. In the other pavilions, such as the English, Swedish, Swiss, etc., it is quietly possible to touch the items. Our textiles hidden behind glass before the visitors' hands feel somewhat awkward. Elsewhere, textiles are touched, examined in detail, while here visitors pass by indifferently. The only somewhat cohesive space was maintained in the so-called industrial hall, where daylight was saved only by the glass-concrete dome, otherwise it would similarly have been necessary to illuminate there — because the glass walls are built all around inside to full height.

It is rumored that the exhibition will be extended into next year. Over the winter (December, January, February), it would be closed. If the extension of the exhibition is realized, then certainly the states that participate in the extended exhibition will make some new adjustments to their exhibitions.

I would recommend that the internal arrangement of the Czechoslovak pavilion be fundamentally changed, that a new unified plan for the adjustment of all exhibitions be developed, which would truly utilize the exhibition possibilities that the all-glass pavilion provides. We can find lessons on how to modernly install exhibitions in the Swiss, Swedish, English, Japanese pavilions, etc.

But primarily, the pavilion should be installed from a national perspective, subordinating the interests of various companies to the whole so that our industrial products imprint in the memory of visitors as — made in Czechoslovakia.

Others are capable of doing this too; we know Swedish steel, Japanese porcelain, English textiles, Swiss clocks, etc. Do we know the manufacturers? No. The name of the country is sufficient.

Stavitel XVI, 1937-1938, s. 68-73.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment