House of Living Culture

Many works by outstanding Czechoslovak architects, designed at the end of the 1960s for a better future, began to serve only as tools of normalization. Additionally, they were anonymous tools, as their authors were often hampered by publication bans. A decade later, the value of these buildings was again denied by a generation reflecting belatedly on postmodernism. It's no wonder that the public still struggles to appreciate them, even though they might have long since accepted them as their own. This is especially true for department stores, which are now subject to new practical requirements. And also for the House of Culture in Budějovické Square in Prague.

Architect Věra Machoninová, winner of this year's Grand Prix award from the Czech Architects' Society for her lifetime achievement, became famous primarily through her work in tandem with her husband, Vladimír Machonin /1, but the House of Culture is one of her independent works. An exception in the oeuvre of both creators is also the fact that its realization did not arise from a competition, as was nearly customary at the time, but was a direct commission from the investor. Věra Machoninová prepared the urban plan for the future Budějovické Square as early as the mid-1960s, and as she recalls in a recently published book of interviews /2, she was recommended to furniture sellers by the then chief architect of the city of Prague, Jiří Voženílek. In the spirit of the time, the House of Culture aimed to centralize the sale of furniture and home accessories and to replace poorly supplied small shops throughout Prague. The design won first prize in 1969 at the Exhibition of Architectural Works. /3 (The urban plan was not followed, only the neighboring building of ČS by Pavla Kordovská from 1992-94 respects it.)

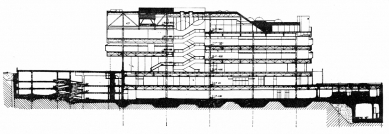

Starting around 1966, designs for houses began to appear in the work of both spouses, which can be imagined as a kind of spatial sandwich, with layers of open space in the form of flat containers suspended from a steel structure. (This is exemplified by the design for a hotel at Pankrác or a computing center at Maniny.) The House of Culture also belongs to this genre but includes at least two new spatial solutions. The first is the closed concrete stair towers, derived from Kahna's "service spaces," which have a Corbusier-inspired shaping by Machoninová. They were born during the design of the House of Culture in 1968 and later surrounded the hexagonal floor plan of the Kotva from three sides, which was originally designed with staircases inside the three edge modules. A specific solution of the House of Culture is the offsetting of individual floors against each other by half the height in section and their connection with a generous escalator hall. The result is a space that continuously extends from the entrance level of the metro station, which is part of the building, to the edge of the top floor. I would compare the floor area to a folded ribbon - emphasizing the similarity to some contemporary realizations. For me, the metal grilles of the ventilation exhausts, which transform the adjacent parking lot into a futuristic metal garden, are a metaphor for the technical style of the building. The building was designed down to the last detail and equipped with custom furniture. Architect Machoninová had enough time after falling out of favor in the 1970s to oversee the details and the execution of the building, and the House of Culture became an architectural and design whole of world caliber. /4

I awaited the outcome of this year's first phase of the House of Culture reconstruction with tension; it was not commissioned by the author, and it was accompanied by mentions of how the building, designed before the oil crisis, is poorly air-conditioned. Fortunately, it only concerned the most necessary matters. However, it did not clear the interiors of inconceptual improvised additions; it only added others, often unfortunately replacing the originals. The stair hall lost not only its stainless-steel railing but primarily one of the escalators and an associated impressive glass walkway. Light yellow painted drywall entered into the materially and color-wise clean structure of the House of Culture and clogged the ground floor and basements. And what to think of painting red-stained wood white? The exterior of the building was affected by the replacement of the glazed ground floor wall with color-inappropriate green double glazing; the corten cladding of the building is still resisting the weather and time. In the second phase, the upper floors of the building will be touched; it is also awaiting "Expansion of existing commercial spaces and new construction of commercial passages in levels -2 and -1", "which will create a pleasant atmosphere". /5

1/ Lukáš Beran, Architect Vladimír Machonin. Art LII, 2004, no. 3,

pp. 271–277.

2/ Petr Ulrich - Petr Vorlík - Beryl Filsaková - Katarína Andrášiová - Lenka Popelová, The Sixties in Architecture Through the Eyes of Witnesses. ČVUT Prague 2006, p. 188.

3/ Exhibition of Architectural Works 1968–69, Czechoslovak Architect XVI, 1970, no. 15, p. 1.

4/ Josef Hrubý, A Few Remarks on the New Building of the House of Culture in Prague, Architecture of the CSSR XXXX, 1982, pp. 24–26.

5/ http://www.prostranstvi.cz/budejovicka/odprior.php

Architect Věra Machoninová, winner of this year's Grand Prix award from the Czech Architects' Society for her lifetime achievement, became famous primarily through her work in tandem with her husband, Vladimír Machonin /1, but the House of Culture is one of her independent works. An exception in the oeuvre of both creators is also the fact that its realization did not arise from a competition, as was nearly customary at the time, but was a direct commission from the investor. Věra Machoninová prepared the urban plan for the future Budějovické Square as early as the mid-1960s, and as she recalls in a recently published book of interviews /2, she was recommended to furniture sellers by the then chief architect of the city of Prague, Jiří Voženílek. In the spirit of the time, the House of Culture aimed to centralize the sale of furniture and home accessories and to replace poorly supplied small shops throughout Prague. The design won first prize in 1969 at the Exhibition of Architectural Works. /3 (The urban plan was not followed, only the neighboring building of ČS by Pavla Kordovská from 1992-94 respects it.)

Starting around 1966, designs for houses began to appear in the work of both spouses, which can be imagined as a kind of spatial sandwich, with layers of open space in the form of flat containers suspended from a steel structure. (This is exemplified by the design for a hotel at Pankrác or a computing center at Maniny.) The House of Culture also belongs to this genre but includes at least two new spatial solutions. The first is the closed concrete stair towers, derived from Kahna's "service spaces," which have a Corbusier-inspired shaping by Machoninová. They were born during the design of the House of Culture in 1968 and later surrounded the hexagonal floor plan of the Kotva from three sides, which was originally designed with staircases inside the three edge modules. A specific solution of the House of Culture is the offsetting of individual floors against each other by half the height in section and their connection with a generous escalator hall. The result is a space that continuously extends from the entrance level of the metro station, which is part of the building, to the edge of the top floor. I would compare the floor area to a folded ribbon - emphasizing the similarity to some contemporary realizations. For me, the metal grilles of the ventilation exhausts, which transform the adjacent parking lot into a futuristic metal garden, are a metaphor for the technical style of the building. The building was designed down to the last detail and equipped with custom furniture. Architect Machoninová had enough time after falling out of favor in the 1970s to oversee the details and the execution of the building, and the House of Culture became an architectural and design whole of world caliber. /4

I awaited the outcome of this year's first phase of the House of Culture reconstruction with tension; it was not commissioned by the author, and it was accompanied by mentions of how the building, designed before the oil crisis, is poorly air-conditioned. Fortunately, it only concerned the most necessary matters. However, it did not clear the interiors of inconceptual improvised additions; it only added others, often unfortunately replacing the originals. The stair hall lost not only its stainless-steel railing but primarily one of the escalators and an associated impressive glass walkway. Light yellow painted drywall entered into the materially and color-wise clean structure of the House of Culture and clogged the ground floor and basements. And what to think of painting red-stained wood white? The exterior of the building was affected by the replacement of the glazed ground floor wall with color-inappropriate green double glazing; the corten cladding of the building is still resisting the weather and time. In the second phase, the upper floors of the building will be touched; it is also awaiting "Expansion of existing commercial spaces and new construction of commercial passages in levels -2 and -1", "which will create a pleasant atmosphere". /5

Lukáš Beran, August 26, 2006

1/ Lukáš Beran, Architect Vladimír Machonin. Art LII, 2004, no. 3,

pp. 271–277.

2/ Petr Ulrich - Petr Vorlík - Beryl Filsaková - Katarína Andrášiová - Lenka Popelová, The Sixties in Architecture Through the Eyes of Witnesses. ČVUT Prague 2006, p. 188.

3/ Exhibition of Architectural Works 1968–69, Czechoslovak Architect XVI, 1970, no. 15, p. 1.

4/ Josef Hrubý, A Few Remarks on the New Building of the House of Culture in Prague, Architecture of the CSSR XXXX, 1982, pp. 24–26.

5/ http://www.prostranstvi.cz/budejovicka/odprior.php

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

28 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

+R+I+P+ ?

pm

29.08.06 10:29

Že by

Jan Kratochvíl

29.08.06 10:10

Profesionální slepota

danielkolman

31.08.06 08:47

pro dk

pm

31.08.06 10:29

pro pana Kolmana

Petra Frantova

31.08.06 10:13

show all comments