Greater London Authority

The capital of the United Kingdom finally has its own town hall. It stands directly opposite the London Tower, which was once not only a royal residence but also a place of execution for noble heads.

The City of London, known as the famed square mile, has had its own mayor since the Middle Ages. However, the city of London, even the "Greater" one, had to do without a central "government" for many years. The term Greater London first appeared in 1882 as a designation for the area controlled by the Metropolitan Police. It began to be used as a political-administrative term in 1889, though it did not include the City, the center, and the oldest part of the metropolis, where only a few thousand residents live permanently, yet around three hundred thousand people work during the day. Today, Greater London is divided into 32 boroughs, each with its own town hall.

It was only in 1889 that the British metropolis got its elected body - the London County Council, which was replaced by the Greater London Council in 1965. The history of this council ended in 1986 when it was abolished by the Conservative government of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The chair of the Greater London Council in the last years was Ken Livingstone, a representative of the left wing of the Labour Party, also known as "Red Ken," who waged a "crusade" against the Prime Minister. The council was housed in a building that now hosts the Marriot hotel and an ocean aquarium, located directly opposite the Parliament across the River Thames, and malicious tongues claim that Thatcher could no longer bear to look at this stronghold of "leftism."

Only after the Labour Party's electoral victory in 1997 did the government decide to restore London's self-governance based on the results of a referendum. In 2000, elections were held not only for twenty-five members of the new self-government but also for the first time in the history of the British metropolis, its mayor was directly elected. In the elections, the charismatic Ken Livingstone convincingly won, although by that time he had been expelled from the Labour Party (he was too "left" for Blair) and sought the favor of Londoners as an independent candidate. Livingstone may have even won due to his ostracism from his party. However, under the law, the powers of the London mayor are very limited. His position is largely representative, although his four-year mandate is supported by far more votes than any member of the House of Commons in the British Parliament.

However, the Greater London Council could not return to the building opposite Parliament. Long before the elections, it was decided to construct a new and original town hall for the representatives of Greater London. A site was found on the right bank of the Thames, directly opposite the medieval Tower. To create the architectural design, none other than one of today's best British architects, Lord Foster of Thames Bank, was commissioned. He is the author of the design of the magnificent Great Hall of the British Museum in London and, among other things, the reconstruction of the Berlin building of the German parliament. "It was another challenge for me to do something for London," says Norman Foster about his project. "I mainly wanted to propose something impressive, but at the same time that would fit into the horizon of our city" he asserts.

He fulfilled his intention. The building, which Londoners affectionately call the "greenhouse" or "egg" due to its shape, is one of the best architectural achievements of recent times.

Old London, which makes up only a tiny part of the total area of the metropolis, is a place where new architecture appears and evolves. Some buildings represent a new era in its ferocity and incompatibility, while others seem to blend into the established environment.

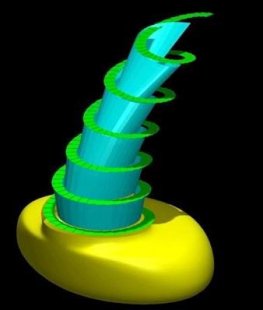

The recently completed building of the London Town Hall belongs to the latter category. The goal was to build an administrative building that would express the unity of London and the transparency of the democratic process of governing this city. It is located just a short distance from the subway station and contains a hall, offices, and public facilities, has 10 floors, and space for 440 employees. From the meeting rooms, there is a view of the river and the skyscrapers in the center of London. The public is also encouraged to use the building. At the top of the structure, there will be an observation terrace with an exhibition room, where receptions will also take place. Transparent walls will allow Londoners passing by to see the London council at work, and people can also stroll along the spiral ramp that winds around the meeting room inside. A café in the basement will also be accessible from the square and the garden at the building. Just as the council's building, squeezed into an oval, connects the city's government and the public, so too will the nighttime lighting in the square come from a single lamp with numerous mirrors on a tall pole, thus the light will not be glaring but will evenly illuminate the entire space.

The shape of the building does not precisely determine where its front and back parts are, and this is perhaps the only thing the authors can be criticized for. The surface area is minimized, making the building one of the most energy-efficient in London. It will be naturally ventilated, and all heat will be recycled. Underground water from deep wells below the building will be used for cooling the house.

As the first of the exhibits in the basement exhibition hall, a model of the city center with all the newly constructed or projected new buildings is on display. Other office spaces will be in nearby buildings that are currently under construction.

The City of London, known as the famed square mile, has had its own mayor since the Middle Ages. However, the city of London, even the "Greater" one, had to do without a central "government" for many years. The term Greater London first appeared in 1882 as a designation for the area controlled by the Metropolitan Police. It began to be used as a political-administrative term in 1889, though it did not include the City, the center, and the oldest part of the metropolis, where only a few thousand residents live permanently, yet around three hundred thousand people work during the day. Today, Greater London is divided into 32 boroughs, each with its own town hall.

It was only in 1889 that the British metropolis got its elected body - the London County Council, which was replaced by the Greater London Council in 1965. The history of this council ended in 1986 when it was abolished by the Conservative government of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The chair of the Greater London Council in the last years was Ken Livingstone, a representative of the left wing of the Labour Party, also known as "Red Ken," who waged a "crusade" against the Prime Minister. The council was housed in a building that now hosts the Marriot hotel and an ocean aquarium, located directly opposite the Parliament across the River Thames, and malicious tongues claim that Thatcher could no longer bear to look at this stronghold of "leftism."

Only after the Labour Party's electoral victory in 1997 did the government decide to restore London's self-governance based on the results of a referendum. In 2000, elections were held not only for twenty-five members of the new self-government but also for the first time in the history of the British metropolis, its mayor was directly elected. In the elections, the charismatic Ken Livingstone convincingly won, although by that time he had been expelled from the Labour Party (he was too "left" for Blair) and sought the favor of Londoners as an independent candidate. Livingstone may have even won due to his ostracism from his party. However, under the law, the powers of the London mayor are very limited. His position is largely representative, although his four-year mandate is supported by far more votes than any member of the House of Commons in the British Parliament.

However, the Greater London Council could not return to the building opposite Parliament. Long before the elections, it was decided to construct a new and original town hall for the representatives of Greater London. A site was found on the right bank of the Thames, directly opposite the medieval Tower. To create the architectural design, none other than one of today's best British architects, Lord Foster of Thames Bank, was commissioned. He is the author of the design of the magnificent Great Hall of the British Museum in London and, among other things, the reconstruction of the Berlin building of the German parliament. "It was another challenge for me to do something for London," says Norman Foster about his project. "I mainly wanted to propose something impressive, but at the same time that would fit into the horizon of our city" he asserts.

He fulfilled his intention. The building, which Londoners affectionately call the "greenhouse" or "egg" due to its shape, is one of the best architectural achievements of recent times.

Jaroslav Beránek, HN víkend 52/2002, s.10-12.

Old London, which makes up only a tiny part of the total area of the metropolis, is a place where new architecture appears and evolves. Some buildings represent a new era in its ferocity and incompatibility, while others seem to blend into the established environment.

The recently completed building of the London Town Hall belongs to the latter category. The goal was to build an administrative building that would express the unity of London and the transparency of the democratic process of governing this city. It is located just a short distance from the subway station and contains a hall, offices, and public facilities, has 10 floors, and space for 440 employees. From the meeting rooms, there is a view of the river and the skyscrapers in the center of London. The public is also encouraged to use the building. At the top of the structure, there will be an observation terrace with an exhibition room, where receptions will also take place. Transparent walls will allow Londoners passing by to see the London council at work, and people can also stroll along the spiral ramp that winds around the meeting room inside. A café in the basement will also be accessible from the square and the garden at the building. Just as the council's building, squeezed into an oval, connects the city's government and the public, so too will the nighttime lighting in the square come from a single lamp with numerous mirrors on a tall pole, thus the light will not be glaring but will evenly illuminate the entire space.

The shape of the building does not precisely determine where its front and back parts are, and this is perhaps the only thing the authors can be criticized for. The surface area is minimized, making the building one of the most energy-efficient in London. It will be naturally ventilated, and all heat will be recycled. Underground water from deep wells below the building will be used for cooling the house.

As the first of the exhibits in the basement exhibition hall, a model of the city center with all the newly constructed or projected new buildings is on display. Other office spaces will be in nearby buildings that are currently under construction.

Martin Krise, HN víkend 52/2002, s.12.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment