Café Era

Café, time, Brno, and architects

The Café Era has long and quite naturally held its place among the incunabula of modern architecture in Brno. However, recently it has somewhat faded from public view, as only the eye of a knowledgeable expert would find in the devastated building located near the famous Tugendhat Villa designed by Mies in Černá Pole the forms of late 1920s architecture. It must be admitted that with the ongoing interest in Brno's interwar architecture, which is often echoed in the projects of followers and imitators of "Brno functionalism," the neglected state of Café Era is a clear local paradox.

The project, which was commissioned for Josef Špunar as a "residential building with a café" in 1927 by Brno architect Josef Kranz, was already symptomatic and exceptional for its time. It was particularly symptomatic from the perspective of the Brno architectural environment, which favored modern tendencies in architecture. Brno architecture in the first two decades of independent Czechoslovakia quickly aligned itself with the concept of architectural purism, notably within the circle of Ernst Wiesner and other Jewish architects. The Brno Czech technical community, with Emil Králík, also leaned towards purist ideology, although it derived from a somewhat different tradition of historicizing architecture with rational and neoclassical elements. With a certain degree of simplification, it can be said that the 1928 exhibition of contemporary culture was the temporal moment when these foundational lines of Brno architecture converged. At that time, there were constructions manifesting both purist aesthetics and constructivist forms, along with those that anticipated the future "International Style."

At the same time, this Brno environment embraced new architectural experiments, whose creators were much more radically inspired by contemporary trends, particularly stemming from Dutch architecture. A clear milestone was the years 1925 and 1926, when well-known European modern architects, especially Jacob Johan Pieter Oud, a city builder in Rotterdam and co-founder of the De Stijl movement, gave lectures in Brno. Shortly thereafter, graduates began to emerge from the newly established Faculty of Architecture at the Czech Technical University. One of the first of them was indeed Josef Kranz (1901-1968), who after studying under Emil Králík and practicing with Jiří Kroha attempted an independent design career in 1927. However, while his first studies for the Memorial of Resistance in Brno and the Slovácko Museum in Uherské Hradiště pointed more to the works of his teachers, the following project for Café Era was completely different.

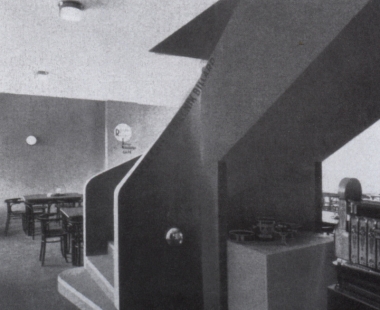

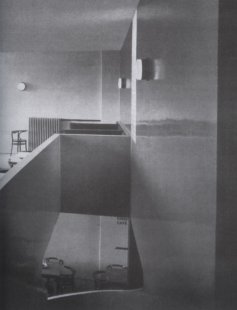

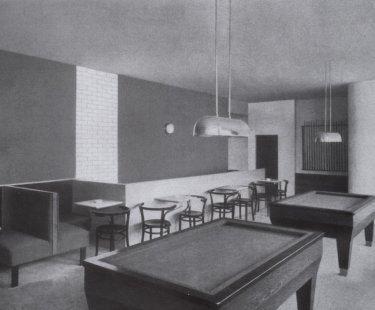

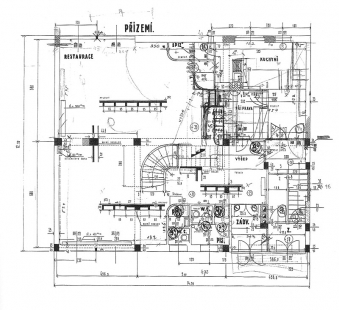

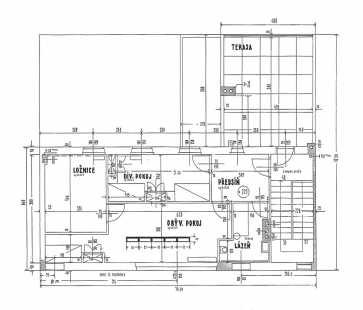

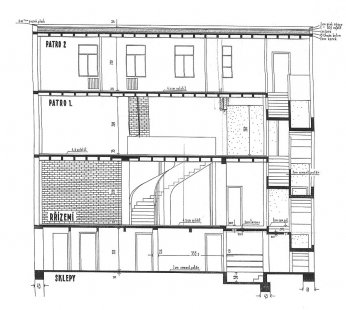

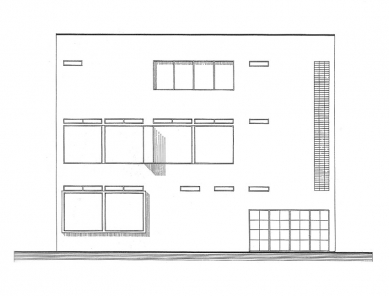

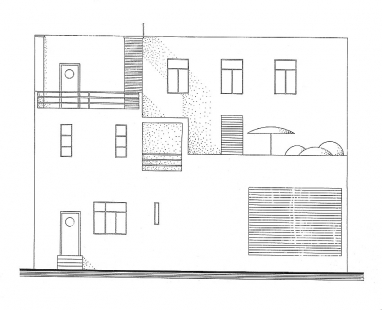

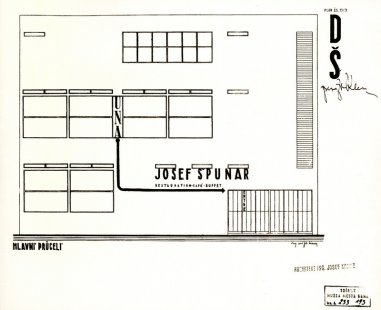

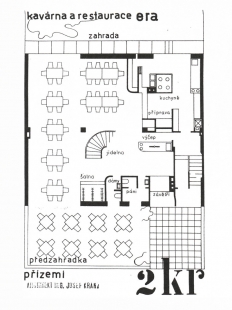

The exceptional nature of the project for Josef Špunar’s house with a café lay in the fact that the emerging architect very radically and directly adhered to the aesthetics of Dutch De Stijl. The task at hand was not architecturally simple: it aimed to connect the café on the ground floor and first floor with the residential spaces on the second floor. Particularly the connection and simultaneous separation of public and private spaces became a considerably challenging problem for the architect. He created at least two basic design variants and ultimately sacrificed the appearance of the rear garden façade for it. He was all the more intrigued by the main façade facing the street, for which he again produced several variant projects. In their evaluation, Zdeněk Kudělka previously pointed out a certain poster-like quality of the main façade. The architect indeed created a surface of geometric elements, which not only referenced the geometric structure of De Stijl but also included a significant informational component. One can note that the main difference between the variant solutions lies primarily in the treatment and incorporation of texts into the façade surface. In the first design with the inscription UNA, the architect and client seemingly manifested the closeness and "derivativeness" of their architectural solution from the Rotterdam café "De Unie" from 1924-25. In another design, the new name ERA was already considered.

Although the connection to the Rotterdam café is indisputable and the entire project can indeed be understood as a declaration of kinship to it, Josef Kranz worked with the composition of geometric elements differently than Oud did some time earlier. The Brno façade consists of a horizontally oriented rectangle, whose surface is divided into three equal sections. Each of these sections is composed of basic graphic elements in the form of

and B and

A A and

A and B

This compositional arrangement, however, stems much more from puristic architectural ideas and is evidently what fundamentally distinguishes it from its Rotterdam counterpart. Such a connection likely led Vladimír Šlapeta to characterize Kranz's project as a sort of "Brno" version of Dutch neoplasticism. At the same time, the compositional variations of the façade clearly do not lack a certain affinity with musical aesthetics, which is probably the reason why the façade evokes (and still evokes) an extraordinarily emotional impression.

In Brno's milieu, such work with architectural purism was not so exceptional at the end of the 1920s. Similar foundations can be pointed to in the contemporaneously emerging projects and works of architect Otto Eisler. His approach to resolving the relationship between purism and new architectural tendencies, however, was much more rational. In this sense, we can distinguish two basic approaches to purism in Brno at the end of the 1920s, one of which we might label "rational" and the other "emotional." It's interesting to note that at the time when Café Era was built (1928-1929), Josef Kranz joined the design office of Bohuslav Fuchs. At that time, Fuchs was designing and constructing the Avion Hotel, in which we find similarly certain elements from the De Stijl environment, but notably also the same "emotional" focus of the originally purist conception.

Both buildings - Kranz's and Fuchs's - represented a considerably radical concept of new architecture in relation to the urban environment in Brno. Fuchs's building was wedged into the older fabric in the city center. Kranz's café was originally built as a standalone structure in Černá Pole, but contemporary evaluations noted its difference from the surroundings: "the exterior makes an ironic counterpart to the heap of rubble on the buildings of the former institute for the blind and the building of the agricultural college in Černá Pole" (Horizont review). If this statement by Roštlapil corresponded with the contemporary thinking of Kranz and Fuchs, then it is apparent that a group of young architects very radically sought to oppose the older classicizing and historicizing tendencies in the urban environment. It was no surprise, then, that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe could enter this environment almost logically with his realization of the Tugendhat Villa. In the context of this most important work in Brno's interwar architecture, it is noteworthy that: (first), the ground plan of Mies reveals a resonance of Dutch geometric composition, and (second), that similar elements were also found in Kranz's ground plan solution, which Mies also introduced: …"the interior is full of light, softened by the curves of masonry partitions. These partitions follow only the function of delineating space without attempting to create a series of niches or rooms."

Even though Kranz's building certainly represented a specific programmatic intention in terms of alignment with the most current trends in European modern architecture, it is remarkable that its author did not establish himself too significantly in Brno. Perhaps it was due to a lack of commissions, or perhaps because of his low self-confidence, that by mid-1929 he left for the postal administration in Brno. Later he also worked in the post-war period at Spojprojekt. Nevertheless, he became the author of many very interesting projects for private houses, in which he developed his principle of "emotional purism," and his name thus became an inseparable part of the history of Brno modern architecture.

The Café Era has long and quite naturally held its place among the incunabula of modern architecture in Brno. However, recently it has somewhat faded from public view, as only the eye of a knowledgeable expert would find in the devastated building located near the famous Tugendhat Villa designed by Mies in Černá Pole the forms of late 1920s architecture. It must be admitted that with the ongoing interest in Brno's interwar architecture, which is often echoed in the projects of followers and imitators of "Brno functionalism," the neglected state of Café Era is a clear local paradox.

The project, which was commissioned for Josef Špunar as a "residential building with a café" in 1927 by Brno architect Josef Kranz, was already symptomatic and exceptional for its time. It was particularly symptomatic from the perspective of the Brno architectural environment, which favored modern tendencies in architecture. Brno architecture in the first two decades of independent Czechoslovakia quickly aligned itself with the concept of architectural purism, notably within the circle of Ernst Wiesner and other Jewish architects. The Brno Czech technical community, with Emil Králík, also leaned towards purist ideology, although it derived from a somewhat different tradition of historicizing architecture with rational and neoclassical elements. With a certain degree of simplification, it can be said that the 1928 exhibition of contemporary culture was the temporal moment when these foundational lines of Brno architecture converged. At that time, there were constructions manifesting both purist aesthetics and constructivist forms, along with those that anticipated the future "International Style."

At the same time, this Brno environment embraced new architectural experiments, whose creators were much more radically inspired by contemporary trends, particularly stemming from Dutch architecture. A clear milestone was the years 1925 and 1926, when well-known European modern architects, especially Jacob Johan Pieter Oud, a city builder in Rotterdam and co-founder of the De Stijl movement, gave lectures in Brno. Shortly thereafter, graduates began to emerge from the newly established Faculty of Architecture at the Czech Technical University. One of the first of them was indeed Josef Kranz (1901-1968), who after studying under Emil Králík and practicing with Jiří Kroha attempted an independent design career in 1927. However, while his first studies for the Memorial of Resistance in Brno and the Slovácko Museum in Uherské Hradiště pointed more to the works of his teachers, the following project for Café Era was completely different.

The exceptional nature of the project for Josef Špunar’s house with a café lay in the fact that the emerging architect very radically and directly adhered to the aesthetics of Dutch De Stijl. The task at hand was not architecturally simple: it aimed to connect the café on the ground floor and first floor with the residential spaces on the second floor. Particularly the connection and simultaneous separation of public and private spaces became a considerably challenging problem for the architect. He created at least two basic design variants and ultimately sacrificed the appearance of the rear garden façade for it. He was all the more intrigued by the main façade facing the street, for which he again produced several variant projects. In their evaluation, Zdeněk Kudělka previously pointed out a certain poster-like quality of the main façade. The architect indeed created a surface of geometric elements, which not only referenced the geometric structure of De Stijl but also included a significant informational component. One can note that the main difference between the variant solutions lies primarily in the treatment and incorporation of texts into the façade surface. In the first design with the inscription UNA, the architect and client seemingly manifested the closeness and "derivativeness" of their architectural solution from the Rotterdam café "De Unie" from 1924-25. In another design, the new name ERA was already considered.

Although the connection to the Rotterdam café is indisputable and the entire project can indeed be understood as a declaration of kinship to it, Josef Kranz worked with the composition of geometric elements differently than Oud did some time earlier. The Brno façade consists of a horizontally oriented rectangle, whose surface is divided into three equal sections. Each of these sections is composed of basic graphic elements in the form of

and B and

A A and

A and B

This compositional arrangement, however, stems much more from puristic architectural ideas and is evidently what fundamentally distinguishes it from its Rotterdam counterpart. Such a connection likely led Vladimír Šlapeta to characterize Kranz's project as a sort of "Brno" version of Dutch neoplasticism. At the same time, the compositional variations of the façade clearly do not lack a certain affinity with musical aesthetics, which is probably the reason why the façade evokes (and still evokes) an extraordinarily emotional impression.

In Brno's milieu, such work with architectural purism was not so exceptional at the end of the 1920s. Similar foundations can be pointed to in the contemporaneously emerging projects and works of architect Otto Eisler. His approach to resolving the relationship between purism and new architectural tendencies, however, was much more rational. In this sense, we can distinguish two basic approaches to purism in Brno at the end of the 1920s, one of which we might label "rational" and the other "emotional." It's interesting to note that at the time when Café Era was built (1928-1929), Josef Kranz joined the design office of Bohuslav Fuchs. At that time, Fuchs was designing and constructing the Avion Hotel, in which we find similarly certain elements from the De Stijl environment, but notably also the same "emotional" focus of the originally purist conception.

Both buildings - Kranz's and Fuchs's - represented a considerably radical concept of new architecture in relation to the urban environment in Brno. Fuchs's building was wedged into the older fabric in the city center. Kranz's café was originally built as a standalone structure in Černá Pole, but contemporary evaluations noted its difference from the surroundings: "the exterior makes an ironic counterpart to the heap of rubble on the buildings of the former institute for the blind and the building of the agricultural college in Černá Pole" (Horizont review). If this statement by Roštlapil corresponded with the contemporary thinking of Kranz and Fuchs, then it is apparent that a group of young architects very radically sought to oppose the older classicizing and historicizing tendencies in the urban environment. It was no surprise, then, that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe could enter this environment almost logically with his realization of the Tugendhat Villa. In the context of this most important work in Brno's interwar architecture, it is noteworthy that: (first), the ground plan of Mies reveals a resonance of Dutch geometric composition, and (second), that similar elements were also found in Kranz's ground plan solution, which Mies also introduced: …"the interior is full of light, softened by the curves of masonry partitions. These partitions follow only the function of delineating space without attempting to create a series of niches or rooms."

Even though Kranz's building certainly represented a specific programmatic intention in terms of alignment with the most current trends in European modern architecture, it is remarkable that its author did not establish himself too significantly in Brno. Perhaps it was due to a lack of commissions, or perhaps because of his low self-confidence, that by mid-1929 he left for the postal administration in Brno. Later he also worked in the post-war period at Spojprojekt. Nevertheless, he became the author of many very interesting projects for private houses, in which he developed his principle of "emotional purism," and his name thus became an inseparable part of the history of Brno modern architecture.

Prof. PhDr. Jiří Kroupa, CSc. (FF MU in Brno)

Reprinted from the magazine ERA 21 (3/2003, pp. 41-42)

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

3 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

kavárna po rekonstrukci

čmelda

10.11.10 11:41

Dle autorů rekonstrukce...

Petr Šmídek

10.11.10 11:39

...Tedy,...

šakal

10.11.10 12:16

show all comments