Royal Saltworks of Arc-et-Senans

The Royal Saltworks of Arc-et-Senans

Salt has historically represented a very valuable commodity that helped to richly fill royal treasuries and secure privileged rights for cities. The places where this raw material was extracted, manufactured, and stored were therefore well-guarded. Salt warehouses resembled fortified strongholds. The salt trade in France was controlled by a monopoly and represented one of the main incomes of the royal court. One of the most ambitious saltworks was the Enlightenment project of an ideal city by Parisian architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, who was a favorite of the French aristocracy for whom he created numerous neoclassical palaces and more than sixty tollhouses at the gates of Paris. Among his works were also a number of visionary projects aimed at literally “healing society.” One of these projects had a chance to see half of its realization.

In the early 1770s, Ledoux was appointed by Louis XV as the inspector of saltworks in the regions of Lorraine and Franché-Comté in eastern France, allowing him to thoroughly familiarize himself with the operation of the saltworks while considering all requirements when designing a new ideal and rational operation.

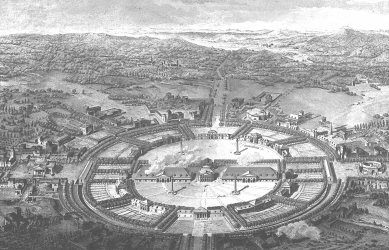

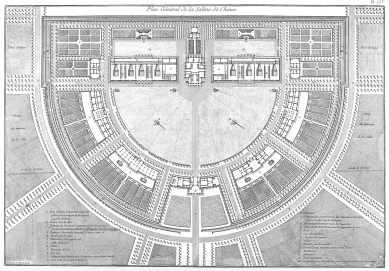

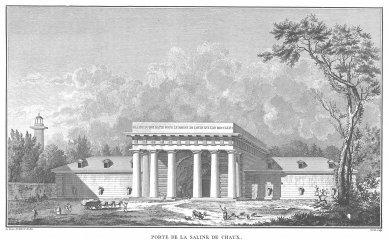

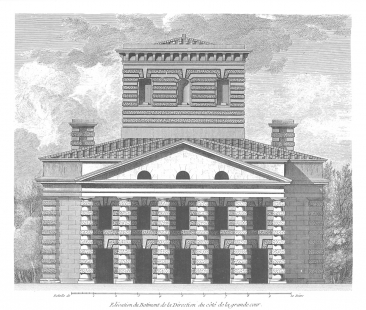

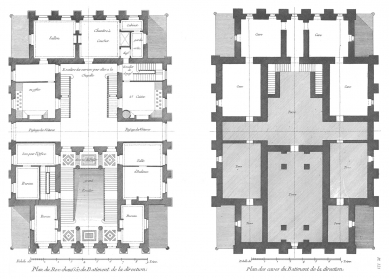

Saltwater is brought to the Arc-et-Senans saltworks through 20-kilometer-long channels from deep mines in the Salins-les-Bains valley, where salt has been extracted since ancient times. The entire saltwork is surrounded by a high stone wall protecting it from external attacks by robbers as well as preventing deserters from escaping. There is only one entrance to this fortress, which is situated on the axis and staged with an impressive forecourt. The entrance building is reminiscent of a Greek temple with eight imposing Doric columns, behind which unexpectedly conceals an artificial cave with gargoyles spewing petrified water. Beyond the magnificent portico, a view opens onto the entire complex with regularly arranged houses resembling military barracks. In the center stands a building reminiscent of a Palladian villa, which housed the management and administration. The management building is preceded by a sextet of unusual columns combining cylindrical elements with low stone blocks. On both sides are the salt production facilities, where burning wood accelerated the evaporation of salty water. Families of officials inhabited two buildings that concluded the linear arrangement. Accommodation for employees and their families took place in four blocks arranged in a semicircle. The life of the employees could easily be monitored from a single spot in the management building (this foreshadowed Bentham’s Panopticon later applied in prisons). In addition to these residential, production, and administrative functions, the saltworks complex also had a public laundry, bakery, and prison. Urbanistically, the entire complex can be read as a fusion of an industrial town arranged according to the rules of ancient theater, where the gaze is directed at the management building resembling a temple. The semicircle was intended by Ledoux to represent the vision of a celestial dome and the path of the sun across the sky. The division into eleven separate buildings by function is, on the other hand, a purely rational consideration. Similarly, the use of spaces was handled pragmatically: behind the factory buildings were outdoor wood storage areas, behind the workers' housing, small gardens were hidden, and the inner semicircular square could remain free and gain a representative character.

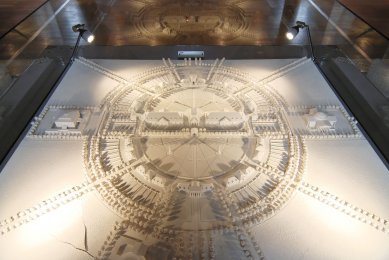

In 1982, the complex of the royal saltwork Arc-et-Senans was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List and today serves as a museum where you can learn more about other visionary projects by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux through models.

Ledoux's Ideal City

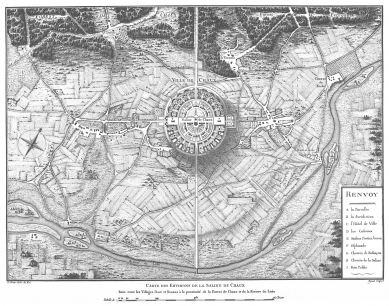

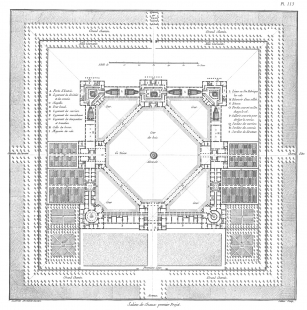

In the second half of the 18th century, the significant French architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux was commissioned to design a new settlement for the royal salt works in Chaux. Around 1780, he completed the first variant of the project, in which he conceived the settlement as a closed quadrilateral, resembling a fortress in appearance. However, in his book on architecture published in 1804, he prints the same theme in his proposal for an "ideal city" with an oval plan and freely built structures in gardens. It is one of the first heralds of the garden city, blending the classical geometrical regularity of the 18th century with a new conception of the relationship between settlements and the natural environment.

It is a very contemporary solution that predates Fourier's circular city and the proposals of Howard and his immediate predecessors. Ledoux described his design as: “Behold the emerging city that contains everything that is necessary.”

In addition to the ideal city, Ledoux also developed several other projects for allegorical buildings in a way that we would most likely today describe as fantastic architecture. This was a period when many other architects were also working on projects for temples of virtue, friendship, and other allegorical and symbolic structures and landscapes, influenced primarily by the philosophical ideas of J. J. Rousseau and later by the French Revolution.

In the early 1770s, Ledoux was appointed by Louis XV as the inspector of saltworks in the regions of Lorraine and Franché-Comté in eastern France, allowing him to thoroughly familiarize himself with the operation of the saltworks while considering all requirements when designing a new ideal and rational operation.

Saltwater is brought to the Arc-et-Senans saltworks through 20-kilometer-long channels from deep mines in the Salins-les-Bains valley, where salt has been extracted since ancient times. The entire saltwork is surrounded by a high stone wall protecting it from external attacks by robbers as well as preventing deserters from escaping. There is only one entrance to this fortress, which is situated on the axis and staged with an impressive forecourt. The entrance building is reminiscent of a Greek temple with eight imposing Doric columns, behind which unexpectedly conceals an artificial cave with gargoyles spewing petrified water. Beyond the magnificent portico, a view opens onto the entire complex with regularly arranged houses resembling military barracks. In the center stands a building reminiscent of a Palladian villa, which housed the management and administration. The management building is preceded by a sextet of unusual columns combining cylindrical elements with low stone blocks. On both sides are the salt production facilities, where burning wood accelerated the evaporation of salty water. Families of officials inhabited two buildings that concluded the linear arrangement. Accommodation for employees and their families took place in four blocks arranged in a semicircle. The life of the employees could easily be monitored from a single spot in the management building (this foreshadowed Bentham’s Panopticon later applied in prisons). In addition to these residential, production, and administrative functions, the saltworks complex also had a public laundry, bakery, and prison. Urbanistically, the entire complex can be read as a fusion of an industrial town arranged according to the rules of ancient theater, where the gaze is directed at the management building resembling a temple. The semicircle was intended by Ledoux to represent the vision of a celestial dome and the path of the sun across the sky. The division into eleven separate buildings by function is, on the other hand, a purely rational consideration. Similarly, the use of spaces was handled pragmatically: behind the factory buildings were outdoor wood storage areas, behind the workers' housing, small gardens were hidden, and the inner semicircular square could remain free and gain a representative character.

In 1982, the complex of the royal saltwork Arc-et-Senans was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List and today serves as a museum where you can learn more about other visionary projects by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux through models.

|

Ledoux's Ideal City

In the second half of the 18th century, the significant French architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux was commissioned to design a new settlement for the royal salt works in Chaux. Around 1780, he completed the first variant of the project, in which he conceived the settlement as a closed quadrilateral, resembling a fortress in appearance. However, in his book on architecture published in 1804, he prints the same theme in his proposal for an "ideal city" with an oval plan and freely built structures in gardens. It is one of the first heralds of the garden city, blending the classical geometrical regularity of the 18th century with a new conception of the relationship between settlements and the natural environment.

It is a very contemporary solution that predates Fourier's circular city and the proposals of Howard and his immediate predecessors. Ledoux described his design as: “Behold the emerging city that contains everything that is necessary.”

In addition to the ideal city, Ledoux also developed several other projects for allegorical buildings in a way that we would most likely today describe as fantastic architecture. This was a period when many other architects were also working on projects for temples of virtue, friendship, and other allegorical and symbolic structures and landscapes, influenced primarily by the philosophical ideas of J. J. Rousseau and later by the French Revolution.

Jiří Hrůza: Theory of Cities, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences Publishing, Prague 1965, pp. 115-117

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment