Crematorium Baumschulenweg

The construction of the crematorium does not belong to frequent architectural commissions, but it hides an immense conceptual charge. The German architect approached it in an ascetic spirit, reminiscent almost cruelly of the monoliths of Tadao Ando. However, he managed to enrich it with several elements that set it apart from the now traditional Japanese style, primarily through the application of turquoise color on steel in the interior; new are the columns in the entrance vestibule (compare Kroupa's design for the pheasantry...), which likely allude to the motif of candlesticks or perhaps direct their vertical form towards the heavens. (jk)

“People die and are unhappy” – architecture cannot change that, but it can still provide a place of rest, a space for silence, even though not even the stones are as heavy as they were in more solid periods of firmer faith in infinity, as was the case in Giza.

The desperate atmosphere we felt at this place five years ago was deterrent. The visitor was warned by an aura devoid of beauty – “Abandon all hope, you who enter here”. The heart of this desolate Campo Santo needed to be replaced. Here, where the deceased receive their last blessing – with all the necessary, sad ceremony: exhibition, decoration, assurance of music, speech, and blessing – the bereaved must express sympathy towards each other and alleviate grief. Here, amidst all the events, a place is needed that balances the ephemeral with the final, that expresses the heaviness of death and allows for relief.

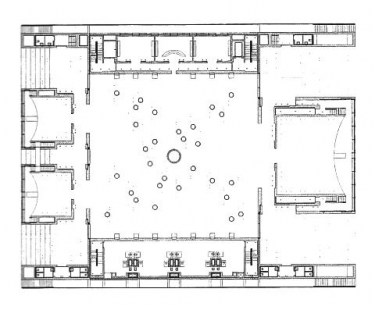

Our final journey is uncertain; neither the church nor the temple of the dead shows the way to nothingness or to paradise. In the sense of embodying freedom and inevitability, it is perhaps the intensity, the structure of the Maghreb mosque that comes closest to fulfilling the task. The Piazza Coperta, a place in the middle of the cenotaph, a meeting place where the individual remains protected. A cauldron of feelings.

The columns terminated by light represent, in this 5000-year-youthful room, the only point of capture for us, sheltered by theocracy – whether it is the theocracy of Moses, Paul, or Muhammad – a cosmological distinction between the inhabited clods of clay and the light of the sun. “The sun is God,” William Turner was right. And this architecture wants nothing more than to unite Father Stone, the heavenly soul, with Lucifer, the angel of light.

Great walls and ancient “doors” evoke past periods when the afterlife held greater significance. They whisper to today’s mourners “Farewell” and “The Great in us is God” – and the water mirror with an egg in the middle of the room asks what the poet meant with the verses:

All eternal springs / flow tirelessly on,

And God? Does He have a beginning? / Perhaps one day God began?

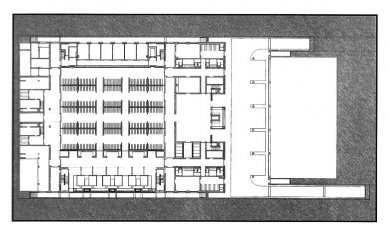

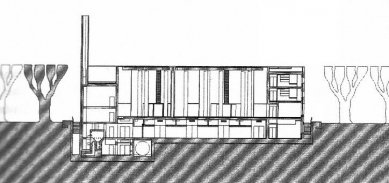

The ceremonial halls – one for 50, the other for 250 visitors – consist of two stone blocks embedded in another casing of glass and metal: the deceased soul, the coffin, the urn has already departed to the realm of light and is now connected with the sky, clouds, trees.

The building expresses, like no other, the indomitable will of the architects. A hollow indivisible block of 50 x 70 meters, 10 meters in the ground, 10 meters above it, one stone, one tombstone, insisting on the material harmony of its spaces. And if the word of truth is on the conjecture of Ludwig Wittgenstein that architecture “compels and glorifies,” that where there is nothing to glorify, architecture cannot exist, then this building glorifies the essence of architecture, celebrates space, the tranquility of walls in light. And architecture cannot do more: “With compassion for the insatiable is a provocation to the eyes, a soup for the world and a star for the rats,” to evoke a clear and fairy-tale image.

“People die and are unhappy” – architecture cannot change that, but it can still provide a place of rest, a space for silence, even though not even the stones are as heavy as they were in more solid periods of firmer faith in infinity, as was the case in Giza.

The desperate atmosphere we felt at this place five years ago was deterrent. The visitor was warned by an aura devoid of beauty – “Abandon all hope, you who enter here”. The heart of this desolate Campo Santo needed to be replaced. Here, where the deceased receive their last blessing – with all the necessary, sad ceremony: exhibition, decoration, assurance of music, speech, and blessing – the bereaved must express sympathy towards each other and alleviate grief. Here, amidst all the events, a place is needed that balances the ephemeral with the final, that expresses the heaviness of death and allows for relief.

Our final journey is uncertain; neither the church nor the temple of the dead shows the way to nothingness or to paradise. In the sense of embodying freedom and inevitability, it is perhaps the intensity, the structure of the Maghreb mosque that comes closest to fulfilling the task. The Piazza Coperta, a place in the middle of the cenotaph, a meeting place where the individual remains protected. A cauldron of feelings.

The columns terminated by light represent, in this 5000-year-youthful room, the only point of capture for us, sheltered by theocracy – whether it is the theocracy of Moses, Paul, or Muhammad – a cosmological distinction between the inhabited clods of clay and the light of the sun. “The sun is God,” William Turner was right. And this architecture wants nothing more than to unite Father Stone, the heavenly soul, with Lucifer, the angel of light.

Great walls and ancient “doors” evoke past periods when the afterlife held greater significance. They whisper to today’s mourners “Farewell” and “The Great in us is God” – and the water mirror with an egg in the middle of the room asks what the poet meant with the verses:

All eternal springs / flow tirelessly on,

And God? Does He have a beginning? / Perhaps one day God began?

The ceremonial halls – one for 50, the other for 250 visitors – consist of two stone blocks embedded in another casing of glass and metal: the deceased soul, the coffin, the urn has already departed to the realm of light and is now connected with the sky, clouds, trees.

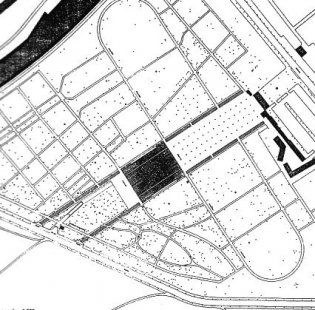

The building expresses, like no other, the indomitable will of the architects. A hollow indivisible block of 50 x 70 meters, 10 meters in the ground, 10 meters above it, one stone, one tombstone, insisting on the material harmony of its spaces. And if the word of truth is on the conjecture of Ludwig Wittgenstein that architecture “compels and glorifies,” that where there is nothing to glorify, architecture cannot exist, then this building glorifies the essence of architecture, celebrates space, the tranquility of walls in light. And architecture cannot do more: “With compassion for the insatiable is a provocation to the eyes, a soup for the world and a star for the rats,” to evoke a clear and fairy-tale image.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment