Residential Complex Barbican

As a result of the bombing during the Second World War, the population of the London district of the City decreased from the original 100,000 to fewer than 6,000 residents. In 1951, therefore, the conservative government led by Prime Minister Winston Churchill was concerned—due to the dramatic drop in local voters—about losing the traditional support of this financial district. Thus, a plan for a significant increase in residential units in the area was implemented.

Based on a competition win, the architects were tasked with designing developments that would not only significantly increase the population density in the City but also offer buildings designated for education and culture. The aim was to attract the widest range of potential residents to the heart of the city.

Initially, the target group was primarily single individuals from the middle management of local banks. The project was not supported by public funds; it was meant to be financed by potential buyers' money. Politically, the goal was to bring residents to the City who were close to conservative ideas, resonating with the contemporary local government.

The original predominant office character of the district was clearly shifted towards residential with a specific political intent. In the final urban and architectural designs of the Barbican, five positions/connections were established:

The first proposal from CP&B was much more modest than the realized version—it combined administrative and residential functions. It was presented in 1955 at a controversial meeting, where it was managed to be pushed through with the help of a flawed count of votes. However, the final support was only gained a year later with the backing of Duncan Sandys, the minister for housing issues, and his intervention with the mayor of the City. In a letter, Sundys advocated that Barbican become a "real residential district" with schools, public spaces, and services—even at the cost of the area yielding lower profits for the municipal treasury. Based on this, CP&B fundamentally expanded the development program.

The architects were inspired by the medieval Italian city, with its fortified towers and water moats. The heart of this seemingly scenographic design was an educational and cultural center shaped like a pyramid located in the very center. The central square was designed around the then-renovated Saint Giles Church. The proposal was rejected due to high population density and lack of undeveloped space.

1956 — Subsequently, the area designated for new development was expanded to the north and south. The blocks were loosened and opened by incorporating extensive open spaces, which CP&B also integrated with landscaping interventions, paved areas, and water features (similarly to their earlier project for the nearby Golden Lane). However, in contrast to the initial solution from 1955, the open spaces now became private, intended for residents. Nine 6-9 story blocks were added. The educational program, which included two schools, was placed in the center of the area.

However, the educational content also required spaces designated for sports and recreation. As a counterpoint, three high-rise buildings (one 31 stories and two 29 stories) were added. The design began to incorporate lowered courtyards and, conversely, elevated pedestrian pathways. The water features were expanded to include a lake, a canal, a fountain, and waterfalls. Compared to the 1955 design, the residential program was relocated to the southern and eastern side of the lot. The offer of housing units expanded, including apartments with four bedrooms.

1959 — The parcel was expanded to encompass the entire area of today's Barbican. The three tower buildings gained a polygonal footprint and 37 floors. The blocks were reshaped into a looser structure with U and Z plans. Some of them were elevated on massive columns, which weakened the feeling of closure and provided new views through the open ground floor. The orthogonality of the plan was disrupted by a diagonal path leading across the main lake, designed by the city building department engineer, who was dissatisfied with the urban planning solution. In order to mitigate the impact of this intervention on the CP&B project, the architects proposed it at least as a viaduct reminiscent of a Roman bridge. However, due to disproportionately high financial costs, this path was eliminated from the project in 1960. The educational program was supplemented by a concert hall for 1,000 seated attendees and a theater for 700 seated (to be used by external companies outside class hours). The semi-circular residential building, in the form of an open amphitheater on the northern side, transitioned from the previous design. An underground parking lot had a capacity of 2,000 cars.

The final project was approved in 1959, and construction began in 1960. The residential complex was completed in 1975, while the Barbican cultural complex finished in 1983.

In Conclusion — The redevelopment of central London aimed to create a "district" where all activities would be separated from newly built roads. A modern approach, most clearly evident in the Barbican design, is the strict separation of automobile traffic from pedestrian pathways. The multifunctionality intended to provide services exceeding the needs of the area represents, however, a direct critique of the segregation of functions imposed by the Athens Charter. CP&B's effort to connect Italian piazzas with then-modern solitary blocks led to an original and innovative fusion of semi-enclosed blocks elevated above ground level and interconnected open spaces, attempting to draw on the famous tradition of British Georgian architecture.

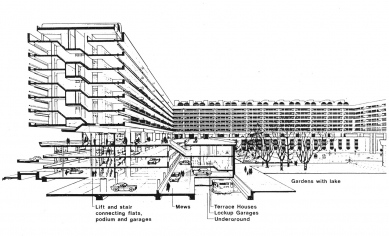

Virtually all buildings in the Barbican are raised on kind of podiums that create access areas to the buildings. This elevated stage acts as a street for pedestrians as well as a space for social interactions and bonds. Urban life thus takes place not on the ground floor but one level above. From here, a pedestrian can look out over the internal open spaces with the lake, similarly to how one would from the ramparts of a medieval fortress.

The perimeter elevated pathway is one of the most characteristic and also controversial features of the Barbican.

Chamberlin, Powell & Bon (CP&B)

Peter Chamberlin (1919 – 1978), Geoffry Powell (1920 – 1999), and Christoph Bon (1921 – 1999) taught at Kingston Polytechnic, now the FA of Kingston University (Kingston University School of Architecture). They were dedicated to social themes, yet their pedagogical activity interested them more than the media coverage of their thoughts on architecture. The Barbican project was acquired relatively early in their careers (they were in their thirties) and occupied them for about the next three decades of their lives.

In 1953, they participated in the IX CIAM Congress in Aix-en-Provence, where Smithson lectured on expanding the analysis of housing from the residential unit to the whole street, neighborhood, and eventually the city; and stimulated thoughts about a much larger scale of housing blocks. These theories aligned with new trends in contemporary British architecture, which emphasized a more pronounced integration of residential buildings into multifunctional construction units, with the separation of automobile traffic from pedestrians.

Based on a competition win, the architects were tasked with designing developments that would not only significantly increase the population density in the City but also offer buildings designated for education and culture. The aim was to attract the widest range of potential residents to the heart of the city.

Initially, the target group was primarily single individuals from the middle management of local banks. The project was not supported by public funds; it was meant to be financed by potential buyers' money. Politically, the goal was to bring residents to the City who were close to conservative ideas, resonating with the contemporary local government.

The original predominant office character of the district was clearly shifted towards residential with a specific political intent. In the final urban and architectural designs of the Barbican, five positions/connections were established:

- The first concerned the direction of masses; it connected long blocks with towers.

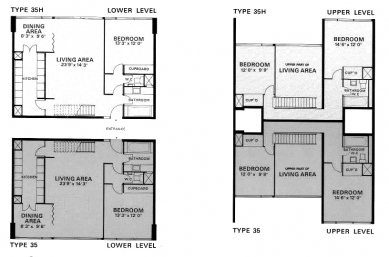

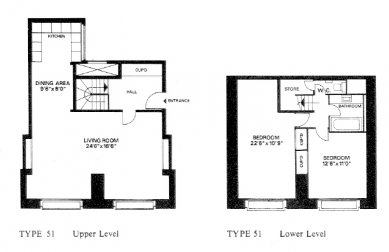

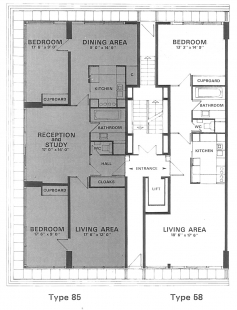

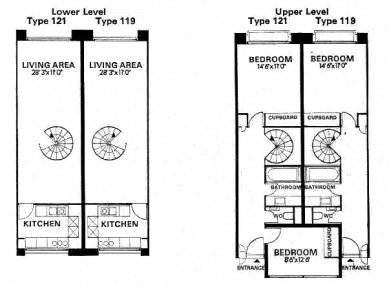

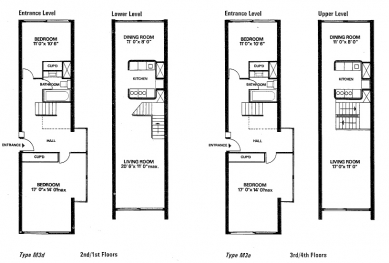

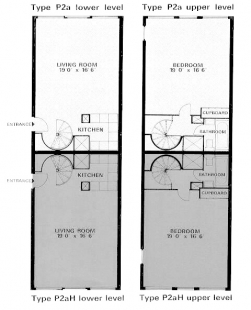

- The second was related to typology; it combined shafts allowing access to high-rise buildings with interior passages and shared staircases for flats on floors and in terrace houses.

- The third represented the choice of semi-open blocks adjoining in some cases to the road, and in other instances integrated into a pedestrian network.

- The fourth position combined private, semi-public, and public open spaces with water features, greenery, and paved areas.

- The fifth connection was the integration of educational and culturally oriented content into the residential program—bearing a significance that far exceeded the location itself.

The first proposal from CP&B was much more modest than the realized version—it combined administrative and residential functions. It was presented in 1955 at a controversial meeting, where it was managed to be pushed through with the help of a flawed count of votes. However, the final support was only gained a year later with the backing of Duncan Sandys, the minister for housing issues, and his intervention with the mayor of the City. In a letter, Sundys advocated that Barbican become a "real residential district" with schools, public spaces, and services—even at the cost of the area yielding lower profits for the municipal treasury. Based on this, CP&B fundamentally expanded the development program.

Building Heights and Population Density

1955 — The first variant of the project was limited to the area located south of the then Barbican street (present-day Beech street). It proposed apartments predominantly with one to two bedrooms for 6,000 residents, as well as exhibition spaces, sports facilities, shops, restaurants, and large administrative blocks. This initial solution consisted of closed rectangular four-story blocks with both public and private courtyards and five twenty-story towers situated at the northwestern end.The architects were inspired by the medieval Italian city, with its fortified towers and water moats. The heart of this seemingly scenographic design was an educational and cultural center shaped like a pyramid located in the very center. The central square was designed around the then-renovated Saint Giles Church. The proposal was rejected due to high population density and lack of undeveloped space.

1956 — Subsequently, the area designated for new development was expanded to the north and south. The blocks were loosened and opened by incorporating extensive open spaces, which CP&B also integrated with landscaping interventions, paved areas, and water features (similarly to their earlier project for the nearby Golden Lane). However, in contrast to the initial solution from 1955, the open spaces now became private, intended for residents. Nine 6-9 story blocks were added. The educational program, which included two schools, was placed in the center of the area.

However, the educational content also required spaces designated for sports and recreation. As a counterpoint, three high-rise buildings (one 31 stories and two 29 stories) were added. The design began to incorporate lowered courtyards and, conversely, elevated pedestrian pathways. The water features were expanded to include a lake, a canal, a fountain, and waterfalls. Compared to the 1955 design, the residential program was relocated to the southern and eastern side of the lot. The offer of housing units expanded, including apartments with four bedrooms.

1959 — The parcel was expanded to encompass the entire area of today's Barbican. The three tower buildings gained a polygonal footprint and 37 floors. The blocks were reshaped into a looser structure with U and Z plans. Some of them were elevated on massive columns, which weakened the feeling of closure and provided new views through the open ground floor. The orthogonality of the plan was disrupted by a diagonal path leading across the main lake, designed by the city building department engineer, who was dissatisfied with the urban planning solution. In order to mitigate the impact of this intervention on the CP&B project, the architects proposed it at least as a viaduct reminiscent of a Roman bridge. However, due to disproportionately high financial costs, this path was eliminated from the project in 1960. The educational program was supplemented by a concert hall for 1,000 seated attendees and a theater for 700 seated (to be used by external companies outside class hours). The semi-circular residential building, in the form of an open amphitheater on the northern side, transitioned from the previous design. An underground parking lot had a capacity of 2,000 cars.

The final project was approved in 1959, and construction began in 1960. The residential complex was completed in 1975, while the Barbican cultural complex finished in 1983.

In Conclusion — The redevelopment of central London aimed to create a "district" where all activities would be separated from newly built roads. A modern approach, most clearly evident in the Barbican design, is the strict separation of automobile traffic from pedestrian pathways. The multifunctionality intended to provide services exceeding the needs of the area represents, however, a direct critique of the segregation of functions imposed by the Athens Charter. CP&B's effort to connect Italian piazzas with then-modern solitary blocks led to an original and innovative fusion of semi-enclosed blocks elevated above ground level and interconnected open spaces, attempting to draw on the famous tradition of British Georgian architecture.

Virtually all buildings in the Barbican are raised on kind of podiums that create access areas to the buildings. This elevated stage acts as a street for pedestrians as well as a space for social interactions and bonds. Urban life thus takes place not on the ground floor but one level above. From here, a pedestrian can look out over the internal open spaces with the lake, similarly to how one would from the ramparts of a medieval fortress.

The perimeter elevated pathway is one of the most characteristic and also controversial features of the Barbican.

Chamberlin, Powell & Bon (CP&B)

Peter Chamberlin (1919 – 1978), Geoffry Powell (1920 – 1999), and Christoph Bon (1921 – 1999) taught at Kingston Polytechnic, now the FA of Kingston University (Kingston University School of Architecture). They were dedicated to social themes, yet their pedagogical activity interested them more than the media coverage of their thoughts on architecture. The Barbican project was acquired relatively early in their careers (they were in their thirties) and occupied them for about the next three decades of their lives.

In 1953, they participated in the IX CIAM Congress in Aix-en-Provence, where Smithson lectured on expanding the analysis of housing from the residential unit to the whole street, neighborhood, and eventually the city; and stimulated thoughts about a much larger scale of housing blocks. These theories aligned with new trends in contemporary British architecture, which emphasized a more pronounced integration of residential buildings into multifunctional construction units, with the separation of automobile traffic from pedestrians.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment