Palazzina The Sunflower

Apartment building Sunflower

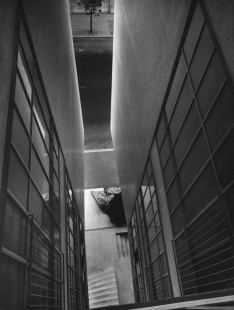

Some buildings are embarrassingly modern: they become a test of good taste, such as 'Casa del Girasole', which was much debated in the early fifties. Its architect, though a man of impressive intellect, did not enjoy complete trust in some architectural circles, and his questionable standing, as reflected in his work, allows him to shed revealing light on the closets full of skeletons. Long before the outbreak of neo-liberty (the Secession revival led by Paolo Portoghesi) called the progressive goals of modern Italian architecture into question, Girasole already seemed quite dubious. What happens inside is by no means modern: routine Roman apartments, arranged along a corridor and stacked into a block raised above a ground floor filled with servants, just as it had been customary throughout Italy until the Quattrocento (15th century). The exterior is undoubtedly modern like the works of Milanese contemporaries. The structure extends above a narrow basement and is as modern as the Pavillon Suisse that stretches over its pilots.

If it were just about window decorations, the gilding of modernity, Girasole could easily be dismissed and one's conscience soothed. But its modernity is not just superficial. Moretti convincingly argues that the division of the façade inevitably stems from the divided floor plan. From bourgeois degenerate design, he created modern architecture. He cleverly smuggles this message in here. The façade is deliberately crafted to appear fake; yet the seemingly unnecessary extension of the walls beyond the rooms is meant to provide space for the opening of shutters. Although the reinforced concrete skeleton is nowhere revealed from the outside, Moretti strip-teases the limbs of classical sculpture among the rustic parts of the lower walls, as if everything were held by secret caryatids.

If it were just about window decorations, the gilding of modernity, Girasole could easily be dismissed and one's conscience soothed. But its modernity is not just superficial. Moretti convincingly argues that the division of the façade inevitably stems from the divided floor plan. From bourgeois degenerate design, he created modern architecture. He cleverly smuggles this message in here. The façade is deliberately crafted to appear fake; yet the seemingly unnecessary extension of the walls beyond the rooms is meant to provide space for the opening of shutters. Although the reinforced concrete skeleton is nowhere revealed from the outside, Moretti strip-teases the limbs of classical sculpture among the rustic parts of the lower walls, as if everything were held by secret caryatids.

Banham, Reyner. Age of the Masters: A Personal View of Modern Architecture. New York: Harper&Row, 1975. p. 94-95

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment