Prada Aoyama Epicenter

Another product of the marketing project Miucci Prada stands in Tokyo's Aoyama shopping district. The American continent was taken over by OMA (besides the headquarters in NY), while H&deM takes care of Europe and Japan. Even such a generous client, who initially gave the architects a free hand, eventually could not avoid disappointment and cuts in plans. Koolhaas's prospects for a branch in San Francisco are slowly fading, and the budget of the Japanese store under review had to undergo a slimming process in the end.

Dome for the Slippers

The store for Prada in Tokyo by Basel architects Herzog & de Meuron is no longer a sales point but a ground for the pleasure of the senses. It towers over the Aoyama shopping district like a shining ice cube with beveled edges. In fact, inside you can buy ordinary shoes and handbags.

Crisis? What crisis? Japan, with its long-term recession, which has been Germany's official nightmare for many months now, is indeed in crisis. But when one begins to look for it, they meet with little success. "Go look beyond Tokyo!", they say. "Come back in two years, then it will be really bad." It seems that the Japanese have managed to maintain a remarkable detachment from their economic debacle. The main principle of this detachment is the motto: "away from physicality." While Germans create a tragic self-flagellating performance from every minor economic stumble and are the first to start saving on food and clothing, the Japanese place self-preservation on initiating their own potential, relying on the belief that wealth will return when they continue to spend lavishly.

The fashion brand Prada, one of the most deeply rooted companies in the minds of young Japanese people, adopted this consumer behavior, for which it currently owes its survival, as a plan for its own strategy. The group, which also included Helmut Lang, Jil Sander, and Church's, became indebted after September 11, the stock market crash, SARS, and the rapid rise of exchange rates. The tradability on the stock market had to be postponed three times, and the flourishing that the clothing industry experienced in the late 90s slowed significantly. Prada did not hesitate to build a sensational new outfit in Tokyo by Basel architects Herzog & de Meuron, who had already constructed its American headquarters in New York and two other projects in Italy.

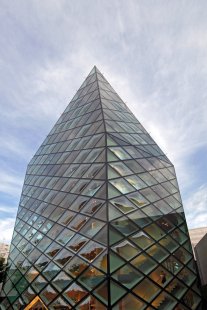

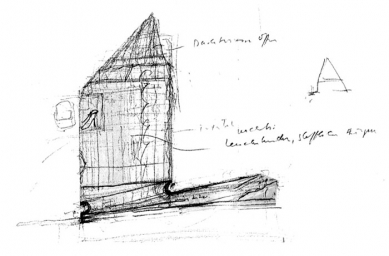

The Prada tower can be seen from afar as it rises above the chaos of the low-rise Aoyama shopping district: a shining ice cube with crushed roof planes: a radical abstraction of the house's shape. H&deM made the building taller and slimmer than those around it in order to create space for a public square in European style. This was not done out of love for passersby, but so that the 2800 square meter building could free itself from the boundaries of the plot (by the way, fewer people can fit in the square than are waiting at an ordinary Tokyo bus stop). Now it stands on the lot like a solitary statue, so it can be admired from all angles. In every expression that this building emits, there is a simultaneous contradiction. When you approach the crystalline boulder closely enough, the seemingly smooth facade shatters into tiny transparent facets resembling an insect's eye. The outer shell consists of hundreds of glass lenses, some of which are bulging and others recessed into the facade. It looks more like a piece of foil that has warped on a hot stove into an irregular shape. While giant video screens are hung in front of facades all over Tokyo to utilize this vertical surface for advertising, the Prada facade, with its analog megapixels, plays a game of wrapping and packaging, familiar from the world of fashion when presenting its goods. But instead of how it usually is with ordinary curtain wall facades, where one can see shoppers inside through the curtain, H&deM convolutes this into doubt: do you see through the fish-eye lens what is inside or indistinct and defragmented representations of it? The same question arises when you look from the store out to the city. The building "undermines any firm and definitive view of the world", the authors proclaim with healthy pathos.

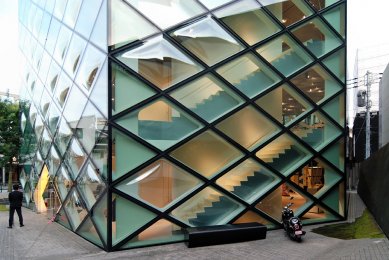

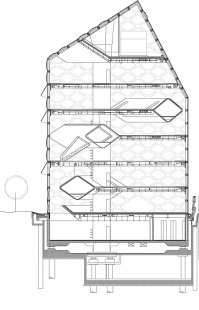

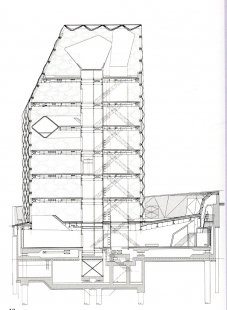

The discourse of unveiling and covering, speaking and contradicting itself that this building radiates has affected architecture itself. The grid of the facade offers no clue about the number of floors, yet it reveals more about the construction than one would expect. The external diagonals, which at first glance seem to have mainly a decorative function, actually carry - together with the slim vertical core and three horizontal "tubes" - the whole building.

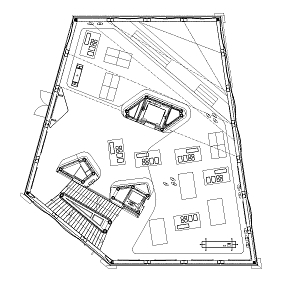

One can only enter through a small opening in the facade's grid. Upon entering, all doubts regarding the materiality that the building aroused from the outside are instantly forgotten. From afar, it appears cold and inaccessible, but inside it creates breathtaking intimacy. It is evidently a classic case of romantic seduction that the building practices with all artistic means. Everything begins already at the entrance on the ground floor, which is (like all other floors) devoid of right angles. A spiraling path begins here through six stories into recessed blind alleys (cloakrooms and VIP rooms), where one feels like being inside a decadent private yacht. The interior furnishings were designed by Herzog & de Meuron themselves, even down to the famous light switch, and as is typical for their work, everything is of the highest quality. The form is based on the curves and diagonals of the main form. However, the most succulent are the materials used. Always great explorers in the field of materials, H&deM were able to experiment more freely than ever before in the service of Prada. And so, they work with another sense important for perceiving fashion, which is touch. The high-fiber carpet is the most common element of this "parkour" of tactile stimuli. It is followed by benches made of shaped foam flakes, opening lamps with silicone shades, vitrines made of fiberglass resembling airplane meal trays, rough oak planks, and leather-covered coat hangers. In the storage area, which is separated from the main mass, moss mats are even sewn in.

H&deM’s Prada-Sensorama presents a new hard currency of luxury and exclusivity in an environment where marble, mirrors, and precious woods have lost value due to inflation. It can be the material or the information: a playful "snorkel" directly taken from Teletubbies that allows you to access the "Prada archive," or the building’s directly ironic base color.

The reason is clear: through the side pathways of images and discourses that threaten the brand, fading interest from the audience, and the banality of inflation’s presence. If someone were to do this with clothes, they would jeopardize this change. This reflection was already the basis for the first of the new "Epicenter-Stores" by Rem Koolhaas in New York. While the one in SoHo flirted with perfectly staged incompleteness, fragility, and a shabby charm (yet costing 40 million dollars), H&deM insist on beauty as a strategy for survival: for customers, the brand, and for the building itself in the land of extravagant skyscrapers: "beauty ensures permanence," adds Jacques Herzog as a maxim.

While Koolhaas showcases intellectual gymnastics, H&deM invites customers to lounge on carpets like Barbarella. While customers in SoHo are stumbling actors in a deconstructivist tale, the Japanese at the plaza, viewing platforms, and caves by H&deM - a glass realm of senses - can not only try on the clothes, but also experiment with and sense three types of perversions whose modus operandi of dressing, undressing, and shedding are: exhibitionism, voyeurism, and fetishism. In the best sense, it is more about architecture than an immoral institution.

Petr Šmídek

Dome for the Slippers

The store for Prada in Tokyo by Basel architects Herzog & de Meuron is no longer a sales point but a ground for the pleasure of the senses. It towers over the Aoyama shopping district like a shining ice cube with beveled edges. In fact, inside you can buy ordinary shoes and handbags.

Crisis? What crisis? Japan, with its long-term recession, which has been Germany's official nightmare for many months now, is indeed in crisis. But when one begins to look for it, they meet with little success. "Go look beyond Tokyo!", they say. "Come back in two years, then it will be really bad." It seems that the Japanese have managed to maintain a remarkable detachment from their economic debacle. The main principle of this detachment is the motto: "away from physicality." While Germans create a tragic self-flagellating performance from every minor economic stumble and are the first to start saving on food and clothing, the Japanese place self-preservation on initiating their own potential, relying on the belief that wealth will return when they continue to spend lavishly.

The fashion brand Prada, one of the most deeply rooted companies in the minds of young Japanese people, adopted this consumer behavior, for which it currently owes its survival, as a plan for its own strategy. The group, which also included Helmut Lang, Jil Sander, and Church's, became indebted after September 11, the stock market crash, SARS, and the rapid rise of exchange rates. The tradability on the stock market had to be postponed three times, and the flourishing that the clothing industry experienced in the late 90s slowed significantly. Prada did not hesitate to build a sensational new outfit in Tokyo by Basel architects Herzog & de Meuron, who had already constructed its American headquarters in New York and two other projects in Italy.

The Prada tower can be seen from afar as it rises above the chaos of the low-rise Aoyama shopping district: a shining ice cube with crushed roof planes: a radical abstraction of the house's shape. H&deM made the building taller and slimmer than those around it in order to create space for a public square in European style. This was not done out of love for passersby, but so that the 2800 square meter building could free itself from the boundaries of the plot (by the way, fewer people can fit in the square than are waiting at an ordinary Tokyo bus stop). Now it stands on the lot like a solitary statue, so it can be admired from all angles. In every expression that this building emits, there is a simultaneous contradiction. When you approach the crystalline boulder closely enough, the seemingly smooth facade shatters into tiny transparent facets resembling an insect's eye. The outer shell consists of hundreds of glass lenses, some of which are bulging and others recessed into the facade. It looks more like a piece of foil that has warped on a hot stove into an irregular shape. While giant video screens are hung in front of facades all over Tokyo to utilize this vertical surface for advertising, the Prada facade, with its analog megapixels, plays a game of wrapping and packaging, familiar from the world of fashion when presenting its goods. But instead of how it usually is with ordinary curtain wall facades, where one can see shoppers inside through the curtain, H&deM convolutes this into doubt: do you see through the fish-eye lens what is inside or indistinct and defragmented representations of it? The same question arises when you look from the store out to the city. The building "undermines any firm and definitive view of the world", the authors proclaim with healthy pathos.

The discourse of unveiling and covering, speaking and contradicting itself that this building radiates has affected architecture itself. The grid of the facade offers no clue about the number of floors, yet it reveals more about the construction than one would expect. The external diagonals, which at first glance seem to have mainly a decorative function, actually carry - together with the slim vertical core and three horizontal "tubes" - the whole building.

One can only enter through a small opening in the facade's grid. Upon entering, all doubts regarding the materiality that the building aroused from the outside are instantly forgotten. From afar, it appears cold and inaccessible, but inside it creates breathtaking intimacy. It is evidently a classic case of romantic seduction that the building practices with all artistic means. Everything begins already at the entrance on the ground floor, which is (like all other floors) devoid of right angles. A spiraling path begins here through six stories into recessed blind alleys (cloakrooms and VIP rooms), where one feels like being inside a decadent private yacht. The interior furnishings were designed by Herzog & de Meuron themselves, even down to the famous light switch, and as is typical for their work, everything is of the highest quality. The form is based on the curves and diagonals of the main form. However, the most succulent are the materials used. Always great explorers in the field of materials, H&deM were able to experiment more freely than ever before in the service of Prada. And so, they work with another sense important for perceiving fashion, which is touch. The high-fiber carpet is the most common element of this "parkour" of tactile stimuli. It is followed by benches made of shaped foam flakes, opening lamps with silicone shades, vitrines made of fiberglass resembling airplane meal trays, rough oak planks, and leather-covered coat hangers. In the storage area, which is separated from the main mass, moss mats are even sewn in.

H&deM’s Prada-Sensorama presents a new hard currency of luxury and exclusivity in an environment where marble, mirrors, and precious woods have lost value due to inflation. It can be the material or the information: a playful "snorkel" directly taken from Teletubbies that allows you to access the "Prada archive," or the building’s directly ironic base color.

The reason is clear: through the side pathways of images and discourses that threaten the brand, fading interest from the audience, and the banality of inflation’s presence. If someone were to do this with clothes, they would jeopardize this change. This reflection was already the basis for the first of the new "Epicenter-Stores" by Rem Koolhaas in New York. While the one in SoHo flirted with perfectly staged incompleteness, fragility, and a shabby charm (yet costing 40 million dollars), H&deM insist on beauty as a strategy for survival: for customers, the brand, and for the building itself in the land of extravagant skyscrapers: "beauty ensures permanence," adds Jacques Herzog as a maxim.

While Koolhaas showcases intellectual gymnastics, H&deM invites customers to lounge on carpets like Barbarella. While customers in SoHo are stumbling actors in a deconstructivist tale, the Japanese at the plaza, viewing platforms, and caves by H&deM - a glass realm of senses - can not only try on the clothes, but also experiment with and sense three types of perversions whose modus operandi of dressing, undressing, and shedding are: exhibitionism, voyeurism, and fetishism. In the best sense, it is more about architecture than an immoral institution.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment