Reconstruction of the Adambräu-Südhaus Brewery

Conversion of the Adambräu brewery in Innsbruck into the Center for Tyrolean Architecture

Introduction

The Adambräu brewery in the center of the Austrian city of Innsbruck, located within sight of the main train station, serves as a good example that not every industrial building needs to be demolished after ceasing operations or, conversely, preserved as a monument. The vertical structure of the brewery has been adapted for the needs of the Center for Tyrolean Architecture (aut.architektur und tirol) and the Archive of Architecture and Construction of the Technical University of Innsbruck (Archiv für Baukunst – Architektur und Ingenieurbau der Universität Innsbruck).

History of the site

The history of beer production at the Adambräu site dates back to 1822, when merchant Franz Josef Adam purchased the family estate Windegg with extensive grounds, an inn, a distillery, stables, and an ornamental garden. Three years later, he obtained brewing rights and built a brewery—the fourth in Innsbruck. The brewery was gradually expanded, converted to steam operation, and changed owners several times. In 1886, a restaurant was added to the brewery according to a design by Josef Spörra; in 1901, the premises were enclosed by a wall, with a garden and music pavilion established for the restaurant according to a design by architect Ludwig Lutz from Munich, and in 1907, Anton Fritz added a bottling plant in the courtyard. Between 1926 and 1931, a major reconstruction of the premises took place. A new brewery and cold store were built according to the design of the prominent architect Loise Welzenbacher in a functionalist style. During the war, 22 Allied bombings severely damaged the surrounding area of Innsbruck's main train station, including the brewery. After the war, the Adambräu brewery became the first facility in Austria to package beverage cans. In the 1960s, a new modern bottling plant was built according to the design of architect Fred Achammer, and the internal transport system was completely modernized. In 1975, a new brewhouse was built with closed cylindro-conical fermentation tanks. Brewery operations were definitively ceased in 1994.

History of the brewhouse structure

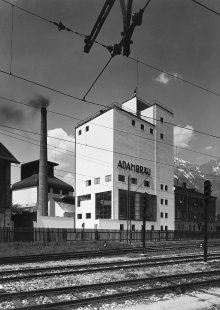

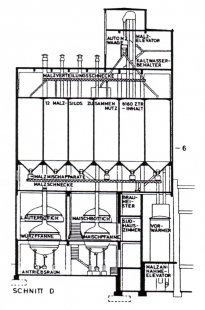

The brewhouse is merely a shell for vertically stacked beer brewing technology—lift for malt, mill, twelve reinforced concrete malt silos, a four-vessel brewhouse, hot and cold water tanks, and a series of other technological elements. The technology was designed by Prof. Theodor Ganzenmüller, then head of the Bavarian Academy for Agriculture and Brewing. The vertical arrangement of individual operations was novel at the time, as processes were usually arranged side by side. The advantage of this arrangement lies in the fact that "raw materials" need to be transported upwards only once. Their subsequent movement is ensured by gravity alone. Processes related to "filling" occur vertically, while "distribution" processes take place horizontally. The modern and economical solution is expressed externally in the elevated proportions of the structure designed by architect Loise Welzenbacher, which at its time was referred to as the Innsbruck skyscraper No. 2, right after the high-rise building of municipal services. (Innsbrucker Wolkenkratzer II – note by I. Gigl, Innsbrucker Nachrichten, 22.8.1931) The building was so innovative that it made headlines and in 1932 was even presented as the only Austrian contribution at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in the exhibition “The International Style: Architecture since 1922”.

BEER PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY: The “finished” malt is delivered to the building from the adjacent malt house. Using an elevator, it is transported to the upper parts of the building, where it is stored in reinforced concrete malt silos. When preparing a brew, the malt is cleaned, crushed, and poured into the mash tun, where it is mixed with warm water. By gradually heating to about 70°C, the starch contained in the malt mash begins to convert to sugar. The content is then transferred to the lauter tun, where it is separated from solid particles. Through further pumping, it reaches the wort kettle, where the wort is boiled. Hops are added during the boiling process. The wort is then transferred to the settling tank and subsequently to the adjacent cold store to cool down. The so-called cold wort then moves to the fermenting cellar. Here, with the addition of yeast that breaks down the sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide, the beer ferments at a temperature of around 10°C. After fermentation, the young beer matures in large tanks in the lager cellar. After filtration, it is packaged into kegs, bottles, or cans and dispatched.

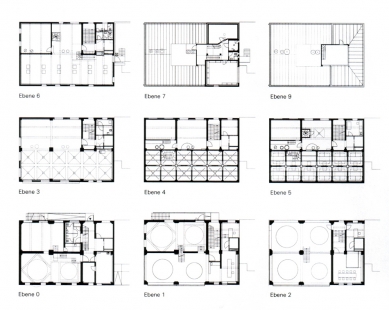

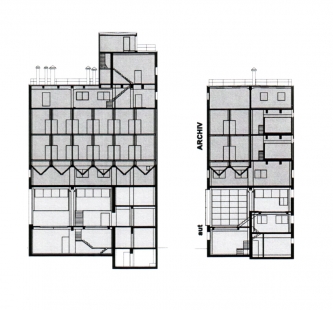

The layout of the building was organized vertically over eight levels. The main vertical circulation was formed by a two-flight staircase in the northwest part of the building. A freight elevator and two malt conveyors near the staircase were used for the transportation of raw materials. Located in the recessed 8th floor were the elevator machine room, automatic scale, and a cold water tank with a capacity of 650 hl. The 7th floor, which has a full floor plan, was served by the elevator distributing the malt to individual silos (located on the 5th and 6th floors) with the help of a screw conveyor. The 5th and 6th floors were largely filled with twelve mentioned reinforced concrete malt silos. The remaining floor area was used for auxiliary operations such as water treatment, milling, malt cleaning, etc. The water treatment tanks were reinforced concrete closed vats with a volume of up to 500 hl. The form of the 4th floor was largely determined by the funnel-shaped discharge openings of the malt silos and dense pipelines for water, steam, and brewing kettle chimneys. Below this floor, in the southeastern part of the building, was the space of the four-vessel brewhouse, with a height of two stories, divided into several height levels. Here stood a quartet of copper vessels (mash tun, lauter tun, wort kettle, settling tank) and a number of fittings (lautering and cooling valves, various taps, etc.). Adjacent to the brewhouse were an office and the brewer's apartment on the 2nd and 3rd floors. The 1st floor housed the brewhouse machinery and a spent grain dryer (waste from brewing beer used, for example, as animal feed and fish food).

The facade enclosing the technology is designed as a strict vertical prism with a marked step in the roof area. The facade is divided into three levels. The high “plinth” of the building (1st - 4th floors) is perforated by window openings and features a pair of large windows in the southeastern corner leading to the double-height brewhouse space. These windows not only serve to bring light to the vessels but also to present the activities happening there. Above this plinth is a windowless block concealing the malt silos. The upper part (7th and 8th floors) is lightened by several windows and the stepping of the roof plane. A prominent feature of the eastern facade of the building—apart from the large glazed surface—is the inscription ADAMBRÄU.

Description of the conversion

After production ceased in 1994, the building came back into the media spotlight. Although it was one of the last fragments of the former industrial district Wilten, it faced demolition. The ongoing zoning plan already counted on the construction of new buildings with predominantly residential functions. In 1995, while the project for new development was already in progress, the monument board of the city declared the brewhouse structure and the adjacent cold store as a monument. However, the preservationists' requirements for the renovation of the building only applied to the facade, which was to remain unchanged. The extent of intervention in the interior of the building was not regulated by them.

From the beginning, the association aut.architektur und tirol (then Architekturforum Tirol) advocated for the preservation of the brewhouse and cold store. After lengthy and complicated negotiations and searching for another partner, a project was created in 1999 to establish a "house of architecture," a joint headquarters for the association aut.architektur und tirol and the Archive of Architecture and Construction of the University of Innsbruck. Unexpectedly, this project had enough power to convince city councilors (the building was and is owned by the city of Innsbruck). It turned out that a building originally designed for beer production could equally well accommodate a new use without major alterations.

Similar to the individual phases of beer production, the new functional units (archive and "forum") are also organized vertically. The function of the upper part of the building—storage spaces for malt silos and water tanks—remains unchanged. Only the stored "material" changes. Instead of malt, books, anthologies, architectural project documentation, architectural models, etc., are now stored here. Storage spaces are complemented by a seminar hall in the area below the silos, with a ceiling articulated by funnel-shaped hoppers, an exhibition hall above the silos, and additional spaces such as meeting rooms, restrooms, and a tea kitchen.

In the part originally designated for the production process—the brewhouse—there is now a multi-level exhibition foyer, where discussions "boil" during exhibitions and openings instead of wort. Besides exhibition spaces, there is also an office and facilities for visitors and staff.

Design began in 2000. The process was complicated by two changes of investor and composition of the building authority. However, these complications were paradoxically beneficial as they allowed time to rethink the approach. Compared to the first project, most of the original structures were preserved, and many planned drastic interventions were reassessed and removed from the project. Here, more than the oversight of the preservationists, cost-saving measures played a role.

According to the original project, a new main entrance was to be built from the southeast, from the busy Südbahnstrasse street, which would have required significant modifications to the layout. By coincidence, however, a decision was made to preserve the original entrance from the courtyard as the main entrance. All other entrances and escape doors were also situated on the courtyard facade, allowing saved interior spaces to be used for the needs of the association aut.architektur und tirol. This made it possible to "save" and reuse the original staircase instead of building a new one. In connection with the staircase, a new elevator was built in place of the original elevator. The areas adjacent to the main landings were slightly expanded.

Forum

Despite all technological equipment being dismantled from the former brewhouse, their "imprint" clearly suggests what occurred here. The quartet of large round openings in the floor of the brewhouse was to be permanently closed. Various material options were considered—steel grating, glass, etc. The final solution is simple. Demountable oak structures were created, a sort of provisional covers, which can be removed from the openings at any time if needed. The identity of the former brewhouse thus remains intact. The most significant intervention in the building's structure was the demolition of the northern wall of the former brewhouse, creating a connection with the administrative spaces. A miniature kitchen was created in the space between the office and the exhibition "lounge".

Archive

Originally, it was planned to remove the entire structure of the malt silos. However, the need to save costs necessitated a different solution. The silos were preserved for the storage of archival materials, and they were interconnected at the points where the dividing concrete walls crossed. The spaces were divided into two levels with a walkable steel grating, creating ideal archival rooms. The funnel-shaped hoppers of each silo were also preserved and used as space for the distribution of technical installations. These hoppers give the seminar hall a certain uniqueness.

Based on previous decisions, the reinforced concrete tanks originally intended for water storage and treatment were also preserved. The tanks were made accessible by cutting rounded entry openings into their walls, creating impressive multifunctional spaces with black-painted inner walls.

All passages of the already dismantled distribution systems through the ceiling slabs were preserved and closed only with glass infill. This way, readable places remain where malt was poured into the silos, where hot water lines ran, steam pipes, or the brewhouse chimney, and an optical connection is created between individual spaces.

Material and color solution

In addressing the material and color of the new elevator cladding, a contrast concept of only black and white surfaces was discovered, eventually used throughout the interior. The existing wall and ceiling structures are painted white, while the floors are made of dark gray terrazzo or linoleum. All metal elements—locksmith elements, fragments of technology, metal doors and covers, window frames, and inserted steel gratings—are coated with black paint. The original steel strip railings were left in place and supplemented with a steel mesh for safety, which, however, is hardly noticeable. The built-in boxes for shelves, restroom facilities, and the kitchen are constructed as a sandwich structure of glued wood with outer layers of steel sheet also in black color.

Fasades

The facades were left untouched. Window openings were refurbished and coated in the color of blacksmith's black. The new entrance doors of the main entrance and escape exit, as well as the fire escape staircase on the northwest facade, are also new. Additional insulation of parts of the building was removed. Where absolutely necessary, an internal insulation system using an insulating drywall was implemented. Surfaces of plaster were only minimally repaired and unified with white paint. The metal letters of the ADAMBRÄU inscription were refurbished and painted black.

Conclusion

The conversion of the Adambräu brewhouse rescued one of the few remaining buildings by the most significant Tyrolean architect of the interwar period, Loise Welzenbacher. Architects Thomas Giner, Erich Wucherer, Andreas Pfeifer, and Rainer Köberl transformed the originally industrial building into a structure for science and culture. They managed to do this while preserving a high degree of authenticity of the original building. One could almost speak of “restoration to original condition”. Paradoxically, this preservationist approach was not the starting point for the design but rather the result of cuts and changes in the original proposal.

Introduction

The Adambräu brewery in the center of the Austrian city of Innsbruck, located within sight of the main train station, serves as a good example that not every industrial building needs to be demolished after ceasing operations or, conversely, preserved as a monument. The vertical structure of the brewery has been adapted for the needs of the Center for Tyrolean Architecture (aut.architektur und tirol) and the Archive of Architecture and Construction of the Technical University of Innsbruck (Archiv für Baukunst – Architektur und Ingenieurbau der Universität Innsbruck).

History of the site

The history of beer production at the Adambräu site dates back to 1822, when merchant Franz Josef Adam purchased the family estate Windegg with extensive grounds, an inn, a distillery, stables, and an ornamental garden. Three years later, he obtained brewing rights and built a brewery—the fourth in Innsbruck. The brewery was gradually expanded, converted to steam operation, and changed owners several times. In 1886, a restaurant was added to the brewery according to a design by Josef Spörra; in 1901, the premises were enclosed by a wall, with a garden and music pavilion established for the restaurant according to a design by architect Ludwig Lutz from Munich, and in 1907, Anton Fritz added a bottling plant in the courtyard. Between 1926 and 1931, a major reconstruction of the premises took place. A new brewery and cold store were built according to the design of the prominent architect Loise Welzenbacher in a functionalist style. During the war, 22 Allied bombings severely damaged the surrounding area of Innsbruck's main train station, including the brewery. After the war, the Adambräu brewery became the first facility in Austria to package beverage cans. In the 1960s, a new modern bottling plant was built according to the design of architect Fred Achammer, and the internal transport system was completely modernized. In 1975, a new brewhouse was built with closed cylindro-conical fermentation tanks. Brewery operations were definitively ceased in 1994.

History of the brewhouse structure

The brewhouse is merely a shell for vertically stacked beer brewing technology—lift for malt, mill, twelve reinforced concrete malt silos, a four-vessel brewhouse, hot and cold water tanks, and a series of other technological elements. The technology was designed by Prof. Theodor Ganzenmüller, then head of the Bavarian Academy for Agriculture and Brewing. The vertical arrangement of individual operations was novel at the time, as processes were usually arranged side by side. The advantage of this arrangement lies in the fact that "raw materials" need to be transported upwards only once. Their subsequent movement is ensured by gravity alone. Processes related to "filling" occur vertically, while "distribution" processes take place horizontally. The modern and economical solution is expressed externally in the elevated proportions of the structure designed by architect Loise Welzenbacher, which at its time was referred to as the Innsbruck skyscraper No. 2, right after the high-rise building of municipal services. (Innsbrucker Wolkenkratzer II – note by I. Gigl, Innsbrucker Nachrichten, 22.8.1931) The building was so innovative that it made headlines and in 1932 was even presented as the only Austrian contribution at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in the exhibition “The International Style: Architecture since 1922”.

BEER PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY: The “finished” malt is delivered to the building from the adjacent malt house. Using an elevator, it is transported to the upper parts of the building, where it is stored in reinforced concrete malt silos. When preparing a brew, the malt is cleaned, crushed, and poured into the mash tun, where it is mixed with warm water. By gradually heating to about 70°C, the starch contained in the malt mash begins to convert to sugar. The content is then transferred to the lauter tun, where it is separated from solid particles. Through further pumping, it reaches the wort kettle, where the wort is boiled. Hops are added during the boiling process. The wort is then transferred to the settling tank and subsequently to the adjacent cold store to cool down. The so-called cold wort then moves to the fermenting cellar. Here, with the addition of yeast that breaks down the sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide, the beer ferments at a temperature of around 10°C. After fermentation, the young beer matures in large tanks in the lager cellar. After filtration, it is packaged into kegs, bottles, or cans and dispatched.

The layout of the building was organized vertically over eight levels. The main vertical circulation was formed by a two-flight staircase in the northwest part of the building. A freight elevator and two malt conveyors near the staircase were used for the transportation of raw materials. Located in the recessed 8th floor were the elevator machine room, automatic scale, and a cold water tank with a capacity of 650 hl. The 7th floor, which has a full floor plan, was served by the elevator distributing the malt to individual silos (located on the 5th and 6th floors) with the help of a screw conveyor. The 5th and 6th floors were largely filled with twelve mentioned reinforced concrete malt silos. The remaining floor area was used for auxiliary operations such as water treatment, milling, malt cleaning, etc. The water treatment tanks were reinforced concrete closed vats with a volume of up to 500 hl. The form of the 4th floor was largely determined by the funnel-shaped discharge openings of the malt silos and dense pipelines for water, steam, and brewing kettle chimneys. Below this floor, in the southeastern part of the building, was the space of the four-vessel brewhouse, with a height of two stories, divided into several height levels. Here stood a quartet of copper vessels (mash tun, lauter tun, wort kettle, settling tank) and a number of fittings (lautering and cooling valves, various taps, etc.). Adjacent to the brewhouse were an office and the brewer's apartment on the 2nd and 3rd floors. The 1st floor housed the brewhouse machinery and a spent grain dryer (waste from brewing beer used, for example, as animal feed and fish food).

The facade enclosing the technology is designed as a strict vertical prism with a marked step in the roof area. The facade is divided into three levels. The high “plinth” of the building (1st - 4th floors) is perforated by window openings and features a pair of large windows in the southeastern corner leading to the double-height brewhouse space. These windows not only serve to bring light to the vessels but also to present the activities happening there. Above this plinth is a windowless block concealing the malt silos. The upper part (7th and 8th floors) is lightened by several windows and the stepping of the roof plane. A prominent feature of the eastern facade of the building—apart from the large glazed surface—is the inscription ADAMBRÄU.

Description of the conversion

After production ceased in 1994, the building came back into the media spotlight. Although it was one of the last fragments of the former industrial district Wilten, it faced demolition. The ongoing zoning plan already counted on the construction of new buildings with predominantly residential functions. In 1995, while the project for new development was already in progress, the monument board of the city declared the brewhouse structure and the adjacent cold store as a monument. However, the preservationists' requirements for the renovation of the building only applied to the facade, which was to remain unchanged. The extent of intervention in the interior of the building was not regulated by them.

From the beginning, the association aut.architektur und tirol (then Architekturforum Tirol) advocated for the preservation of the brewhouse and cold store. After lengthy and complicated negotiations and searching for another partner, a project was created in 1999 to establish a "house of architecture," a joint headquarters for the association aut.architektur und tirol and the Archive of Architecture and Construction of the University of Innsbruck. Unexpectedly, this project had enough power to convince city councilors (the building was and is owned by the city of Innsbruck). It turned out that a building originally designed for beer production could equally well accommodate a new use without major alterations.

Similar to the individual phases of beer production, the new functional units (archive and "forum") are also organized vertically. The function of the upper part of the building—storage spaces for malt silos and water tanks—remains unchanged. Only the stored "material" changes. Instead of malt, books, anthologies, architectural project documentation, architectural models, etc., are now stored here. Storage spaces are complemented by a seminar hall in the area below the silos, with a ceiling articulated by funnel-shaped hoppers, an exhibition hall above the silos, and additional spaces such as meeting rooms, restrooms, and a tea kitchen.

In the part originally designated for the production process—the brewhouse—there is now a multi-level exhibition foyer, where discussions "boil" during exhibitions and openings instead of wort. Besides exhibition spaces, there is also an office and facilities for visitors and staff.

Design began in 2000. The process was complicated by two changes of investor and composition of the building authority. However, these complications were paradoxically beneficial as they allowed time to rethink the approach. Compared to the first project, most of the original structures were preserved, and many planned drastic interventions were reassessed and removed from the project. Here, more than the oversight of the preservationists, cost-saving measures played a role.

According to the original project, a new main entrance was to be built from the southeast, from the busy Südbahnstrasse street, which would have required significant modifications to the layout. By coincidence, however, a decision was made to preserve the original entrance from the courtyard as the main entrance. All other entrances and escape doors were also situated on the courtyard facade, allowing saved interior spaces to be used for the needs of the association aut.architektur und tirol. This made it possible to "save" and reuse the original staircase instead of building a new one. In connection with the staircase, a new elevator was built in place of the original elevator. The areas adjacent to the main landings were slightly expanded.

Forum

Despite all technological equipment being dismantled from the former brewhouse, their "imprint" clearly suggests what occurred here. The quartet of large round openings in the floor of the brewhouse was to be permanently closed. Various material options were considered—steel grating, glass, etc. The final solution is simple. Demountable oak structures were created, a sort of provisional covers, which can be removed from the openings at any time if needed. The identity of the former brewhouse thus remains intact. The most significant intervention in the building's structure was the demolition of the northern wall of the former brewhouse, creating a connection with the administrative spaces. A miniature kitchen was created in the space between the office and the exhibition "lounge".

Archive

Originally, it was planned to remove the entire structure of the malt silos. However, the need to save costs necessitated a different solution. The silos were preserved for the storage of archival materials, and they were interconnected at the points where the dividing concrete walls crossed. The spaces were divided into two levels with a walkable steel grating, creating ideal archival rooms. The funnel-shaped hoppers of each silo were also preserved and used as space for the distribution of technical installations. These hoppers give the seminar hall a certain uniqueness.

Based on previous decisions, the reinforced concrete tanks originally intended for water storage and treatment were also preserved. The tanks were made accessible by cutting rounded entry openings into their walls, creating impressive multifunctional spaces with black-painted inner walls.

All passages of the already dismantled distribution systems through the ceiling slabs were preserved and closed only with glass infill. This way, readable places remain where malt was poured into the silos, where hot water lines ran, steam pipes, or the brewhouse chimney, and an optical connection is created between individual spaces.

Material and color solution

In addressing the material and color of the new elevator cladding, a contrast concept of only black and white surfaces was discovered, eventually used throughout the interior. The existing wall and ceiling structures are painted white, while the floors are made of dark gray terrazzo or linoleum. All metal elements—locksmith elements, fragments of technology, metal doors and covers, window frames, and inserted steel gratings—are coated with black paint. The original steel strip railings were left in place and supplemented with a steel mesh for safety, which, however, is hardly noticeable. The built-in boxes for shelves, restroom facilities, and the kitchen are constructed as a sandwich structure of glued wood with outer layers of steel sheet also in black color.

Fasades

The facades were left untouched. Window openings were refurbished and coated in the color of blacksmith's black. The new entrance doors of the main entrance and escape exit, as well as the fire escape staircase on the northwest facade, are also new. Additional insulation of parts of the building was removed. Where absolutely necessary, an internal insulation system using an insulating drywall was implemented. Surfaces of plaster were only minimally repaired and unified with white paint. The metal letters of the ADAMBRÄU inscription were refurbished and painted black.

Conclusion

The conversion of the Adambräu brewhouse rescued one of the few remaining buildings by the most significant Tyrolean architect of the interwar period, Loise Welzenbacher. Architects Thomas Giner, Erich Wucherer, Andreas Pfeifer, and Rainer Köberl transformed the originally industrial building into a structure for science and culture. They managed to do this while preserving a high degree of authenticity of the original building. One could almost speak of “restoration to original condition”. Paradoxically, this preservationist approach was not the starting point for the design but rather the result of cuts and changes in the original proposal.

Jan Pustějovský

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment