Extensions to Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller

Uitbreiding Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller

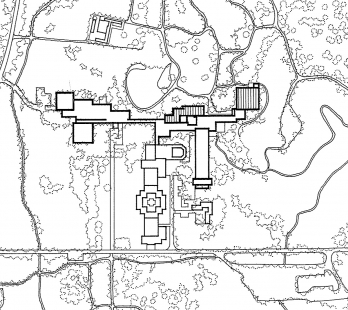

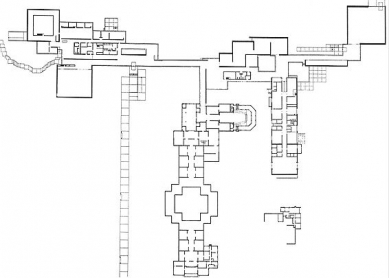

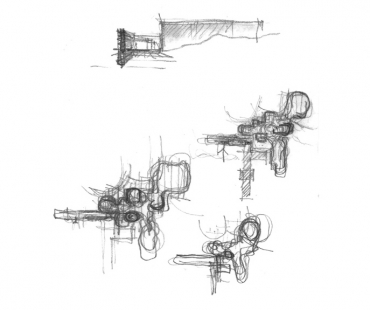

The extensions to the Kroller-Muller Museum were necessary to expand the original building of 1938 by Henry van de Velde with offices, work areas, exhibition space, storage space, and public facilities including a hall, cafetaria, cloakrooms, and toilets. The execution of this prestigious commission meant a lot for Quist's development as an architect but as much for architectural discussion in the seventies. The building develops two themes current at the time, and crass opposites: the architecture of the small-scale and congenial (the 'settlement') against formal, autonomous architecture. These extensions became a 'settlement' when they divided up and invaded the woods at two or three places, there to establish three small outposts comprising a maintenance workshop, an office, and auditoria. No matter where one stands, there is always only part of the museum building in sight.

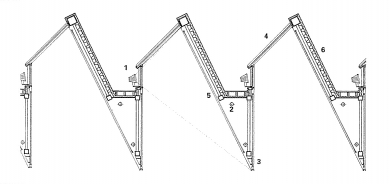

It is a reticent building. Whoever appraoches close to the facade observes a change: the architecture shakes off the metaphors of hospitality and naturalness and becomes autonomuos, self-sufficient. The coice of materials and the detailing give the facade a distinctly technical, architectonic air. At the extended glass sections it is enhanced by a further, remarkable element: there the roof is no longer expressed, transforming these masses into vast 'minimal' sculptures. The interior contains a similar vacillation between nature and culture. Here, however, the glass corridors ar no longer sculptures, rather they strengthen greatly the image of 'settlement': through the glazed skin the architecture dissolves into trees and shrubs. But at the same time the extremely axial development of the space within is demonstratively architectural; once again the materials and perfect detail abruptly shut out the surroundings and steer the visitor's attention to the culture within. The settlement has now disappeared. Architectura is playing tricks with the woods.

It is a reticent building. Whoever appraoches close to the facade observes a change: the architecture shakes off the metaphors of hospitality and naturalness and becomes autonomuos, self-sufficient. The coice of materials and the detailing give the facade a distinctly technical, architectonic air. At the extended glass sections it is enhanced by a further, remarkable element: there the roof is no longer expressed, transforming these masses into vast 'minimal' sculptures. The interior contains a similar vacillation between nature and culture. Here, however, the glass corridors ar no longer sculptures, rather they strengthen greatly the image of 'settlement': through the glazed skin the architecture dissolves into trees and shrubs. But at the same time the extremely axial development of the space within is demonstratively architectural; once again the materials and perfect detail abruptly shut out the surroundings and steer the visitor's attention to the culture within. The settlement has now disappeared. Architectura is playing tricks with the woods.

0 comments

add comment