Swiss Re Headquarters

The Royal Institute of British Architects awarded its most prestigious prize in October 2004

RIBA

Just as the Czech Chamber of Architects oversees progress in Czech architecture, British architecture is cared for by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), whose primary mission is to support the development of British architecture towards higher qualities in all its aspects. The history of this organization dates back to deep into the first half of the 19th century. It was founded with the support of the royal court in 1837, the same year Queen Victoria ascended to the British throne. The queen herself endorsed the awarding of the Royal Golden Medal in 1848; this prize is the oldest architectural award within RIBA and is awarded to the most significant personalities in the field of architecture as a tribute for a lifetime of work and contribution to the development of architecture.

STIRLING PRIZE

On the other hand, the Stirling Prize is one of the youngest awards given under the RIBA umbrella. It was established in 1996 with the aim of highlighting and rewarding a specific realization from the past year, which, as in the case of architects, is characterized by the highest contribution to the development of architecture, progressive solutions, and quality concepts. The winner receives a reward in the form of advertising on RIBA's pages, partner publications, Channel 4, and also a significant amount of £20,000. The Royal Stirling Prize refers to one of the most significant British architects of the 20th century, Sir James Stirling (1926-1992). Stirling originated from Glasgow, studied architecture in the north at the University of Liverpool, but after completing his studies moved to London, where he set up a design office. Notable realizations include the Technical Services Building of the University of Leicester, the Social Studies Centre in Berlin, and the State Gallery in Stuttgart. In 1981, he received the Pritzker Prize.

The Stirling Prize has recognized the following projects: Laban Dance Centre in Deptford, London, designed by the Swiss office Herzog & de Meuron (2003), Gateshead Millennium Bridge by Wilkinson Eyre Architects (2002), who also won the Stirling Prize for the Magna Centre Rotherham (2001), Peckham Library from Alsop and Störmer (2000), NatWest Media Centre at Lord's Cricket Ground by Future Systems (1999), Imperial War Museum in Duxford designed by Foster and Partners (1998), Michael Wilford, Music School in Stuttgart (1997), and the first prize was awarded in 1996 to architect Stephen Hodder for the Centenary Building at the University of Salford.

FINAL

Like the Czech Grand Prix, the Stirling Prize is awarded to buildings submitted for the competition. An expert jury selects the best projects that make it to the finals. The period between the selection of finalists and the announcement of the winner is a time for discussions about the contributions of individual buildings. Visitors can view panels with photo documentation and brief descriptions of the projects in the exhibition halls of RIBA at 66 Portland Place in central London, and they can even express their opinions about the competition by voting, from which a winner is drawn. The media promotion of the competition doesn't end there. The main event occurs on the day of the winner's announcement, when a ceremonial event is broadcast during prime time on Channel 4. This year, the finalists included truly magnificent projects: Kunsthaus in Graz by Peter Cook and Colin Fournier, the The Spire memorial in Dublin by Ian Ritchie Architects, the Imperial War Museum in Manchester by Studio Daniel Libeskind, and the Phoenix Initiative in Coventry by MacCormac and Jamieson Prichard, with two nominations making it to the finals for the office of Foster and Partners: Swiss Re Headquarters, 30 St. Mary Axe, and Business Academy Bexley.

AND THE WINNER IS:

Both specialists and the general public unanimously agreed on the winner: Swiss Re Headquarters, 30 St. Mary Axe. There may not be a single architecture magazine that hasn't devoted at least one page to the attention of 30 St. Mary Axe. Moreover, few buildings have so drastically altered the face of the city's skyline and architecture as a whole. Conservative Londoners had their doubts about the realization. Very quickly, ambiguous references to the building's silhouette emerged, culminating in mischievous comments about the genital shape of the skyscraper at 30 St. Mary Axe in sexual unity with the Greater London Authority Building on the opposite side of the Thames. The strength of popular commentary also penetrated into professional articles, whose authors were evidently thrilled with the general interest in both realizations.

What is it about the building at 30 St. Mary Axe that makes it so interesting that it won the Stirling Prize? Primarily, its relevance in design. Foster and Partners have been long engaged in addressing the solutions for administrative buildings. Unlike many other creators, they perceive the resolution of an administrative building as a complex of interior and exterior, where the exterior relates not only to the façade but also to the environment as such. They do not subordinate one to the other; instead, they combine them, thus finding new solutions.

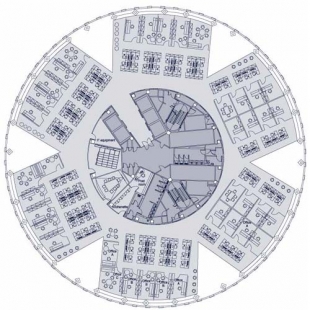

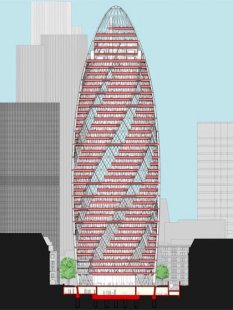

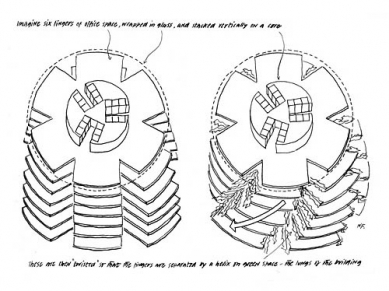

During the design process, the creators had to focus most on the question of natural elements. The site acquired from an older office building, which was destroyed in a bomb explosion by the IRA in 1992, lies on a "windy hill," and all high-rise buildings struggle with the weather conditions here. The designers of the nearby Tower 42 attempted to minimize wind effects by chamfering the building's corners. Foster and Partners prepared a solution that minimizes wind gusts to the smallest possible degree: circular floor plans, cigar-shaped forms, and smooth glass walls suspended on diagonally oriented networks. The building's structure is supported by a reinforced concrete core, into which all types of communications are concentrated. From the center, individual floors unfold like a hat's brim. The circular floor plan of the floors is divided into six conventionally rectangular office spaces by triangular cutouts. This division is based on the practical need for the separation of spaces for various tenants (half of the area is used for its needs by the investor: Swiss Re). The triangular cutouts are positioned one above the other and create a shaft with relaxation terraces. In the façade, they can be recognized by their different shading, creating a large spiral. Here, we arrive at perhaps the most interesting structural aesthetic element on the façade. The building's structure is in motion; each floor is rotated by one seventy-second of the length of the perimeter. Besides the outer aesthetic expression, this has a positive contribution to the creation of the inner space of the shaft with relaxation terraces. It increases contact among people between different floors while preserving a degree of intimacy. According to the architects, this enhances a positive sense of community among the workers. The terraces are open to free space, while the offices are separated from the glazed façade by their own glass wall. The interstitial space serves as a chimney distributing fresh air to the offices. The system operates independently based on physical laws without the need for significant mechanical control. The resulting energy savings are very desirable today when office air conditioning has huge energy demands. The complete glazing of the outer walls provides ample daylight to the interior from all sides and in moments of contemplation, when the worker tears their eyes away from the computer, they can enjoy a fantastic view of London.

In connection with the construction, the immediate surroundings of the building were also addressed. By itself, it is not completely uninteresting, but in relation to the building, it has been somewhat inadequately processed. The generous monumental concept of the building is placed into an almost comical system of water cascades circling the building, regularly interrupted by bridges that allow access to the colonnade. The bridges also have railings on each side. This completely dilutes the striking element of anchoring the structure of the glazed façade network to the ground. The curbs around the little trees seem almost unnecessary to mention. This leads to one general conclusion. Today, there is a huge number of very talented architects, but they lack the sensitivity to process public space. This applies not only to the Swiss Re headquarters but also to Prague's Danube House, whose atrium solution is equally tragic, or is it globally...?

RIBA

Just as the Czech Chamber of Architects oversees progress in Czech architecture, British architecture is cared for by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), whose primary mission is to support the development of British architecture towards higher qualities in all its aspects. The history of this organization dates back to deep into the first half of the 19th century. It was founded with the support of the royal court in 1837, the same year Queen Victoria ascended to the British throne. The queen herself endorsed the awarding of the Royal Golden Medal in 1848; this prize is the oldest architectural award within RIBA and is awarded to the most significant personalities in the field of architecture as a tribute for a lifetime of work and contribution to the development of architecture.

STIRLING PRIZE

On the other hand, the Stirling Prize is one of the youngest awards given under the RIBA umbrella. It was established in 1996 with the aim of highlighting and rewarding a specific realization from the past year, which, as in the case of architects, is characterized by the highest contribution to the development of architecture, progressive solutions, and quality concepts. The winner receives a reward in the form of advertising on RIBA's pages, partner publications, Channel 4, and also a significant amount of £20,000. The Royal Stirling Prize refers to one of the most significant British architects of the 20th century, Sir James Stirling (1926-1992). Stirling originated from Glasgow, studied architecture in the north at the University of Liverpool, but after completing his studies moved to London, where he set up a design office. Notable realizations include the Technical Services Building of the University of Leicester, the Social Studies Centre in Berlin, and the State Gallery in Stuttgart. In 1981, he received the Pritzker Prize.

The Stirling Prize has recognized the following projects: Laban Dance Centre in Deptford, London, designed by the Swiss office Herzog & de Meuron (2003), Gateshead Millennium Bridge by Wilkinson Eyre Architects (2002), who also won the Stirling Prize for the Magna Centre Rotherham (2001), Peckham Library from Alsop and Störmer (2000), NatWest Media Centre at Lord's Cricket Ground by Future Systems (1999), Imperial War Museum in Duxford designed by Foster and Partners (1998), Michael Wilford, Music School in Stuttgart (1997), and the first prize was awarded in 1996 to architect Stephen Hodder for the Centenary Building at the University of Salford.

FINAL

Like the Czech Grand Prix, the Stirling Prize is awarded to buildings submitted for the competition. An expert jury selects the best projects that make it to the finals. The period between the selection of finalists and the announcement of the winner is a time for discussions about the contributions of individual buildings. Visitors can view panels with photo documentation and brief descriptions of the projects in the exhibition halls of RIBA at 66 Portland Place in central London, and they can even express their opinions about the competition by voting, from which a winner is drawn. The media promotion of the competition doesn't end there. The main event occurs on the day of the winner's announcement, when a ceremonial event is broadcast during prime time on Channel 4. This year, the finalists included truly magnificent projects: Kunsthaus in Graz by Peter Cook and Colin Fournier, the The Spire memorial in Dublin by Ian Ritchie Architects, the Imperial War Museum in Manchester by Studio Daniel Libeskind, and the Phoenix Initiative in Coventry by MacCormac and Jamieson Prichard, with two nominations making it to the finals for the office of Foster and Partners: Swiss Re Headquarters, 30 St. Mary Axe, and Business Academy Bexley.

AND THE WINNER IS:

Both specialists and the general public unanimously agreed on the winner: Swiss Re Headquarters, 30 St. Mary Axe. There may not be a single architecture magazine that hasn't devoted at least one page to the attention of 30 St. Mary Axe. Moreover, few buildings have so drastically altered the face of the city's skyline and architecture as a whole. Conservative Londoners had their doubts about the realization. Very quickly, ambiguous references to the building's silhouette emerged, culminating in mischievous comments about the genital shape of the skyscraper at 30 St. Mary Axe in sexual unity with the Greater London Authority Building on the opposite side of the Thames. The strength of popular commentary also penetrated into professional articles, whose authors were evidently thrilled with the general interest in both realizations.

What is it about the building at 30 St. Mary Axe that makes it so interesting that it won the Stirling Prize? Primarily, its relevance in design. Foster and Partners have been long engaged in addressing the solutions for administrative buildings. Unlike many other creators, they perceive the resolution of an administrative building as a complex of interior and exterior, where the exterior relates not only to the façade but also to the environment as such. They do not subordinate one to the other; instead, they combine them, thus finding new solutions.

During the design process, the creators had to focus most on the question of natural elements. The site acquired from an older office building, which was destroyed in a bomb explosion by the IRA in 1992, lies on a "windy hill," and all high-rise buildings struggle with the weather conditions here. The designers of the nearby Tower 42 attempted to minimize wind effects by chamfering the building's corners. Foster and Partners prepared a solution that minimizes wind gusts to the smallest possible degree: circular floor plans, cigar-shaped forms, and smooth glass walls suspended on diagonally oriented networks. The building's structure is supported by a reinforced concrete core, into which all types of communications are concentrated. From the center, individual floors unfold like a hat's brim. The circular floor plan of the floors is divided into six conventionally rectangular office spaces by triangular cutouts. This division is based on the practical need for the separation of spaces for various tenants (half of the area is used for its needs by the investor: Swiss Re). The triangular cutouts are positioned one above the other and create a shaft with relaxation terraces. In the façade, they can be recognized by their different shading, creating a large spiral. Here, we arrive at perhaps the most interesting structural aesthetic element on the façade. The building's structure is in motion; each floor is rotated by one seventy-second of the length of the perimeter. Besides the outer aesthetic expression, this has a positive contribution to the creation of the inner space of the shaft with relaxation terraces. It increases contact among people between different floors while preserving a degree of intimacy. According to the architects, this enhances a positive sense of community among the workers. The terraces are open to free space, while the offices are separated from the glazed façade by their own glass wall. The interstitial space serves as a chimney distributing fresh air to the offices. The system operates independently based on physical laws without the need for significant mechanical control. The resulting energy savings are very desirable today when office air conditioning has huge energy demands. The complete glazing of the outer walls provides ample daylight to the interior from all sides and in moments of contemplation, when the worker tears their eyes away from the computer, they can enjoy a fantastic view of London.

In connection with the construction, the immediate surroundings of the building were also addressed. By itself, it is not completely uninteresting, but in relation to the building, it has been somewhat inadequately processed. The generous monumental concept of the building is placed into an almost comical system of water cascades circling the building, regularly interrupted by bridges that allow access to the colonnade. The bridges also have railings on each side. This completely dilutes the striking element of anchoring the structure of the glazed façade network to the ground. The curbs around the little trees seem almost unnecessary to mention. This leads to one general conclusion. Today, there is a huge number of very talented architects, but they lack the sensitivity to process public space. This applies not only to the Swiss Re headquarters but also to Prague's Danube House, whose atrium solution is equally tragic, or is it globally...?

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

clanok

matus

11.10.08 10:37

show all comments