Government District in St. Pölten

I've heard a lot about the new government quarter of Lower Austria in St. Pölten, mostly negative.

In 1986, St. Pölten became the capital of Lower Austria. The lack of administrative spaces for government parties and the Lower Austrian government itself resulted in the organization of an international competition in 1990 (from Czech architects, among others, architects from JKA participated). As revealed by the chief city architect, the best proposal did not win, but rather the one that was easiest to implement and operationally satisfying.

The basic urban concept by architect Ernst Hoffmann unfolds in a contextual relation with the surroundings. Hoffman responds to the river Traisen, which defines the territory to the east and the existing urban structure of historical St. Pölten to the north. The main entrance to the new quarter logically continues the operational structure of the historical city and essentially expresses its effort to actively engage with the city's organism. The urban design of the government quarter follows the latest ideas and dogmas of European urbanism, particularly in the spatial aspect of the proposal. In 1997, the first session of the regional parliament took place, formally marking the beginning of life in the government quarter.

Most reactions to the government quarter stem from the discovery of a non-functional urban space, uniform architecture, and a certain rootlessness of the entire area. What causes these characteristics? Personally, I see the fundamental contradiction of the entire quarter in the mismatch of content and form. The functional content attempts to shape the area into a mixed, healthy city; however, the prevailing administrative functions and the lack of housing degrade the entire concept. Almost purely an office city exhibits all the signs of mono-functional spaces, particularly the unentangled spatiotemporal diagram of interests in the area. The previously mentioned absence of housing could have been offset by the realization of citywide and regional cultural activity objects. However, the unfortunate location of these functions within the territory did not support the overall liveliness of the quarter. Cultural objects are situated in a common cluster, rather than a more pleasant dispersion throughout the area. The overall conception of solitary objects and textures in the area is not good. The only solitary objects that function in the area as spatial accents are the Regional House – the seat of the Regional Parliament and the Klangturm – Tower of Tones. The Festival House, Regional Museum, Regional Archive, and Regional Library are in a situation of "marginal observers of the territory" instead of active spatial creators.

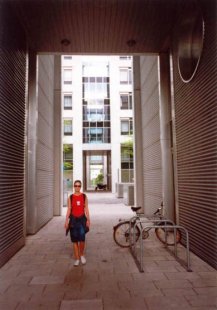

The place where the lines of content and form did not meet is undoubtedly the covered boulevard leading from the gateway building of architect Podrecca to the building of the Regional Parliament. One expects a logical placement of shops and commercial activities in this passage, and that indeed happens. Unfortunately, the missing interest group works most of the day in the upper floors of the buildings or is just leaving for Vienna, where the officials reside. Well, a factory for politics.

The government quarter in St. Pölten is a high-quality architectural and construction work, but unfortunately not an urban work. As it turns out, urbanism is not just a spatial game of objects concentrated under the sun; it is a multidisciplinary field in which economics and theories of flows play an increasingly larger role. The urbanism of the government quarter is a pioneer in the process of rectifying modernist schisms in urbanism, but unfortunately still suffers from teething problems. The primacy of European urbanism remains the domain of Berlin, where ideas of the city of short links, functionally mixed city, and the city of European tradition are successfully implemented.

As architecture and urbanism enter the 21st century, there are no lasting and respected values. In the case of the Lower Austrian government quarter, the street does not function as a street, the city house does not act as a city house, and the square is not a square even though it formally appears to be so. Archetypal confusion in architecture is also entering urbanism.

In 1986, St. Pölten became the capital of Lower Austria. The lack of administrative spaces for government parties and the Lower Austrian government itself resulted in the organization of an international competition in 1990 (from Czech architects, among others, architects from JKA participated). As revealed by the chief city architect, the best proposal did not win, but rather the one that was easiest to implement and operationally satisfying.

The basic urban concept by architect Ernst Hoffmann unfolds in a contextual relation with the surroundings. Hoffman responds to the river Traisen, which defines the territory to the east and the existing urban structure of historical St. Pölten to the north. The main entrance to the new quarter logically continues the operational structure of the historical city and essentially expresses its effort to actively engage with the city's organism. The urban design of the government quarter follows the latest ideas and dogmas of European urbanism, particularly in the spatial aspect of the proposal. In 1997, the first session of the regional parliament took place, formally marking the beginning of life in the government quarter.

Most reactions to the government quarter stem from the discovery of a non-functional urban space, uniform architecture, and a certain rootlessness of the entire area. What causes these characteristics? Personally, I see the fundamental contradiction of the entire quarter in the mismatch of content and form. The functional content attempts to shape the area into a mixed, healthy city; however, the prevailing administrative functions and the lack of housing degrade the entire concept. Almost purely an office city exhibits all the signs of mono-functional spaces, particularly the unentangled spatiotemporal diagram of interests in the area. The previously mentioned absence of housing could have been offset by the realization of citywide and regional cultural activity objects. However, the unfortunate location of these functions within the territory did not support the overall liveliness of the quarter. Cultural objects are situated in a common cluster, rather than a more pleasant dispersion throughout the area. The overall conception of solitary objects and textures in the area is not good. The only solitary objects that function in the area as spatial accents are the Regional House – the seat of the Regional Parliament and the Klangturm – Tower of Tones. The Festival House, Regional Museum, Regional Archive, and Regional Library are in a situation of "marginal observers of the territory" instead of active spatial creators.

The place where the lines of content and form did not meet is undoubtedly the covered boulevard leading from the gateway building of architect Podrecca to the building of the Regional Parliament. One expects a logical placement of shops and commercial activities in this passage, and that indeed happens. Unfortunately, the missing interest group works most of the day in the upper floors of the buildings or is just leaving for Vienna, where the officials reside. Well, a factory for politics.

The government quarter in St. Pölten is a high-quality architectural and construction work, but unfortunately not an urban work. As it turns out, urbanism is not just a spatial game of objects concentrated under the sun; it is a multidisciplinary field in which economics and theories of flows play an increasingly larger role. The urbanism of the government quarter is a pioneer in the process of rectifying modernist schisms in urbanism, but unfortunately still suffers from teething problems. The primacy of European urbanism remains the domain of Berlin, where ideas of the city of short links, functionally mixed city, and the city of European tradition are successfully implemented.

As architecture and urbanism enter the 21st century, there are no lasting and respected values. In the case of the Lower Austrian government quarter, the street does not function as a street, the city house does not act as a city house, and the square is not a square even though it formally appears to be so. Archetypal confusion in architecture is also entering urbanism.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment