Anne Street Garden Villas

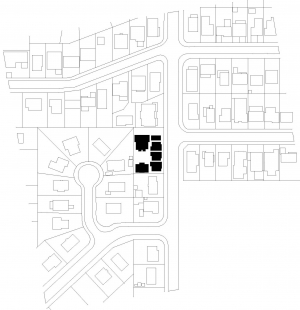

Anne Street Garden Villas is a series of 7 social housing dwellings in Southport on the Gold Coast. The design was informed by ideas from our Density and Diversity Done Well Open Idea Competition entry, as well as stakeholder workshops and local social housing design reviews.

Anne Street Garden Villas is one of ten social housing demonstration project being delivered by a collaborative partnership between Housing Partnerships Office, Building Asset Services and the Office of the Queensland Government Architect. The demonstration projects will inform the new design guidelines for future social housing in Queensland.

TO CREATE LIVEABLE, FORWARD-THINKING SOCIAL HOUSING, WE WERE ENCOURAGED TO CHALLENGE CONVENTIONS OF SOCIAL HOUSING AND EMPLOY SMALL DESIGN MOVES THAT WE THOUGHT COULD HAVE A BIG IMPACT – ESPECIALLY WHEN IT CAME TO GIVING TENANTS A SENSE OF OWNERSHIP OVER THEIR RESIDENCE.

In high-density social housing developments, tenants do not always feel settled in their own home. There are so many small signals – like the large carpark fronting the street – that give the development an institutional feel. This not only makes it challenging for tenants to feel ownership and pride about their home, it also creates a divide between the complex and the rest of the neighbourhood.

Our initial feelings about this problem were confirmed via a series of human-centred design workshops. In these workshops, current social housing tenants revealed a clear desire for nesting and being part of a community, while still having the sense of autonomy we get from a traditional freestanding home.

With these findings in mind, we looked for ways to make the experience of entering the Anne Street Garden Villas more akin to the experience of coming home in the traditional sense. To facilitate this, we made 4 key design decisions.

Ways we achieved this include:

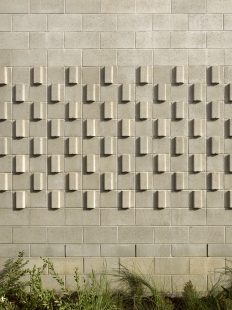

Applying a different exterior colour to each residence, in order give each home its own distinguishing character.

Building each dwelling as a stand-alone form.

Private entrances to street-facing homes, as well as direct access to the shared garden space.

Low fences between residences to allow for conversation with neighbours, without any intrusion into private space.

These elements are intended to make the complex feel more like a village than a communal living arrangement. They achieve this goal by clearly drawing a line between communal areas and the private perimeter of each home.

This decision was important, because we want the development to make a positive contribution to its neighborhood. And the inviting street frontage will help to foster goodwill and connection between residents and the neighbourhood.

As for the carpark, it has been located to the side of the units, so that carports and driveways do not dominate the street frontage.

Let’s say you’re feeling unwell and heading to a doctor’s appointment or running late for work, the last thing you want is to have to stop and make small talk with someone crossing your path. In order to fulfill this need for autonomy and independence, we wanted to create a design solution that gives residents the ability to mediate how and when they engage with each other.

This was achieved by introducing entry and exit points away from congregation spaces, in addition to pathways through communal areas.

Cumulatively, the intention of these decisions is to foster independence without sacrificing the connection between all tenants and the rest of the street.

EVERYONE DESERVES A HOME TO FEEL PROUD OF. THE QUESTION IS – HOW CAN WE HELP SOCIAL HOUSING RESIDENTS DEVELOP A PERSONAL CONNECTION WITH THEIR HOME? THIS IS THE PROBLEM WE WANTED TO SOLVE WHEN DESIGNING THE ANNE STREET GARDEN VILLAS.

To begin designing a new home for a private residential project, we talk to the people who will call the place home. By learning how they live, we can create the perfect spot for that morning coffee ritual, nooks for the kids and spaces for personal interests (like a music room or place to display art, for instance).

Comparatively, when we design high-density commercial projects such as apartments or townhouses, they’re created with a very specific buyer in mind. While we don’t know details such as whether buyers will possess an art collection, we do have a clear idea of whether the developer wants to attract families, downsizers or professional couples.

Designing this way allows us to create homes that feel special and – importantly – safe. But in social housing projects, we rarely have the same opportunity to learn about the residents in such an insightful manner as these other types of residential projects. That means we have to make a lot of assumptions about how the occupants will use their homes, limiting our ability to create a sensitive design response.

Overcoming this barrier is what makes Anne Street Garden Villas such an important project. We were thrilled to have the opportunity to better connect with social housing residents in order to challenge conventional architectural approaches to design.

Here is what we learned.

TWO WORKSHOPS = A WHOLE LOT OF HUMAN CONNECTION

In collaboration with Housing Partnerships Office, Building Asset Services and the Office of the Queensland Government Architect, we attended a series of private workshops to ensure our project looks towards the future, rather than what has been done in the past.

These workshops allowed us to engage with a cross-section of residents from two different social housing locations. We walked through the home of a single mother on laundry day and were invited to reframe our thinking of disability by a resident with hearing difficulties, among others.

Participants were also taken through a series of activities designed to shed light on ways their homes could better support their livelihoods and wellbeing. To dive deep, we went beyond the round-circle focus group format and used tools such as prompt cards and drawing activities to allow each individual to fully express themselves.

The stories we heard added richness to our thinking we could never have achieved in isolation. So we listened and put pen to paper in order to really understand what’s working and what isn’t in the design of affordable housing. It was incredibly heartening to hear participants express how much it meant to have someone sit down and listen to their views.

While we don’t know who will live in Anne Street Garden Villas as yet, the opportunity to speak with tenants who have first-hand experience of social housing allowed us to better understand how their homes can better serve them.

WHAT YOU CAN LEARN FROM OUR FINDINGS

We are sharing the insights from these workshops in the hope they help to elevate other social housing projects around Australia.

There were many ideas shared in the workshops, which can be loosely categorised into these key themes:

Community: Car parking is a key consideration for social housing projects, but car parks often take up valuable space that could be used to encourage interaction between residents and bring people together. We were eager to find ways to address both of these concerns.

Privacy: While community interaction is important for mental health and feeling secure at home, residents also expressed the need for choice in how they engage with neighbours. Ideas suggested included visual privacy in their homes and private spaces for daily tasks (for example, not being forced to use shared laundry facilities).

Accessibility: Disabilities vary widely, and our workshops invited us to consider new ways for general social housing units to support the independence of a wider variety of people.

Adaptability: As society changes, it is vital that social housing does too. Themes including working from home and the changing demographics of social housing residents emerged in the workshop, allowing us to better understand how these homes will be used both now and into the future.

It emerged that in order for residents to feel a sense of belonging at home, they need to feel connected to their immediate surrounds and neighbours.

Following this workshop, we determined the primary challenge for this project: to devise practical ways of creating a village while supporting individual autonomy.

Our visit to existing social housing revealed that simple everyday pleasures – like a small garden with sunlight and drainage, or somewhere to host a barbecue – are lacking. These insights illustrate how social housing can become so much more than a roof and four walls when designed with people in mind (just as we would do in a private residential project).

We’re also thrilled that the success of these process means the Queensland Government is now in the process of establishing a panel of architects to conduct regular research and workshops with social housing tenants.

Anne Street Garden Villas is one of ten social housing demonstration project being delivered by a collaborative partnership between Housing Partnerships Office, Building Asset Services and the Office of the Queensland Government Architect. The demonstration projects will inform the new design guidelines for future social housing in Queensland.

TO CREATE LIVEABLE, FORWARD-THINKING SOCIAL HOUSING, WE WERE ENCOURAGED TO CHALLENGE CONVENTIONS OF SOCIAL HOUSING AND EMPLOY SMALL DESIGN MOVES THAT WE THOUGHT COULD HAVE A BIG IMPACT – ESPECIALLY WHEN IT CAME TO GIVING TENANTS A SENSE OF OWNERSHIP OVER THEIR RESIDENCE.

In high-density social housing developments, tenants do not always feel settled in their own home. There are so many small signals – like the large carpark fronting the street – that give the development an institutional feel. This not only makes it challenging for tenants to feel ownership and pride about their home, it also creates a divide between the complex and the rest of the neighbourhood.

Our initial feelings about this problem were confirmed via a series of human-centred design workshops. In these workshops, current social housing tenants revealed a clear desire for nesting and being part of a community, while still having the sense of autonomy we get from a traditional freestanding home.

With these findings in mind, we looked for ways to make the experience of entering the Anne Street Garden Villas more akin to the experience of coming home in the traditional sense. To facilitate this, we made 4 key design decisions.

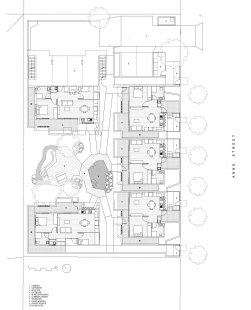

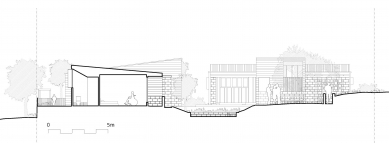

1. A village of small-scale homes

To guide our thinking, we thought of each residence as a small-scale home nestled within a village. This allowed us to integrate a series of subtle cues into the design that gives each home its own identity.Ways we achieved this include:

Applying a different exterior colour to each residence, in order give each home its own distinguishing character.

Building each dwelling as a stand-alone form.

Private entrances to street-facing homes, as well as direct access to the shared garden space.

Low fences between residences to allow for conversation with neighbours, without any intrusion into private space.

These elements are intended to make the complex feel more like a village than a communal living arrangement. They achieve this goal by clearly drawing a line between communal areas and the private perimeter of each home.

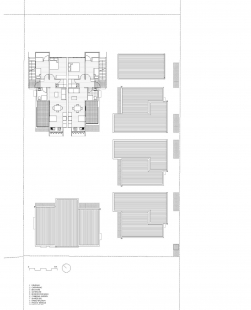

2. Residential street frontage

These small-scale homes face the street, ensuring the development has a direct connection with the neighbourhood. Placing single-level homes at the front of the site and two-level residences to the rear ensures Anne Street Garden does not impose on its surroundings.This decision was important, because we want the development to make a positive contribution to its neighborhood. And the inviting street frontage will help to foster goodwill and connection between residents and the neighbourhood.

As for the carpark, it has been located to the side of the units, so that carports and driveways do not dominate the street frontage.

3. Multiple modes of access

In developments that lack private modes of access, residents feel as though their comings and goings are on display for the entire complex.Let’s say you’re feeling unwell and heading to a doctor’s appointment or running late for work, the last thing you want is to have to stop and make small talk with someone crossing your path. In order to fulfill this need for autonomy and independence, we wanted to create a design solution that gives residents the ability to mediate how and when they engage with each other.

This was achieved by introducing entry and exit points away from congregation spaces, in addition to pathways through communal areas.

4. Own address for tenants

Each home in Anne Street Garden Villas has its own street number, letterbox and entry. We worked with regulators to get an address for each home, which will help each resident to feel a sense of individuality from their fellow tenants.Cumulatively, the intention of these decisions is to foster independence without sacrificing the connection between all tenants and the rest of the street.

EVERYONE DESERVES A HOME TO FEEL PROUD OF. THE QUESTION IS – HOW CAN WE HELP SOCIAL HOUSING RESIDENTS DEVELOP A PERSONAL CONNECTION WITH THEIR HOME? THIS IS THE PROBLEM WE WANTED TO SOLVE WHEN DESIGNING THE ANNE STREET GARDEN VILLAS.

To begin designing a new home for a private residential project, we talk to the people who will call the place home. By learning how they live, we can create the perfect spot for that morning coffee ritual, nooks for the kids and spaces for personal interests (like a music room or place to display art, for instance).

Comparatively, when we design high-density commercial projects such as apartments or townhouses, they’re created with a very specific buyer in mind. While we don’t know details such as whether buyers will possess an art collection, we do have a clear idea of whether the developer wants to attract families, downsizers or professional couples.

Designing this way allows us to create homes that feel special and – importantly – safe. But in social housing projects, we rarely have the same opportunity to learn about the residents in such an insightful manner as these other types of residential projects. That means we have to make a lot of assumptions about how the occupants will use their homes, limiting our ability to create a sensitive design response.

Overcoming this barrier is what makes Anne Street Garden Villas such an important project. We were thrilled to have the opportunity to better connect with social housing residents in order to challenge conventional architectural approaches to design.

Here is what we learned.

TWO WORKSHOPS = A WHOLE LOT OF HUMAN CONNECTION

In collaboration with Housing Partnerships Office, Building Asset Services and the Office of the Queensland Government Architect, we attended a series of private workshops to ensure our project looks towards the future, rather than what has been done in the past.

These workshops allowed us to engage with a cross-section of residents from two different social housing locations. We walked through the home of a single mother on laundry day and were invited to reframe our thinking of disability by a resident with hearing difficulties, among others.

Participants were also taken through a series of activities designed to shed light on ways their homes could better support their livelihoods and wellbeing. To dive deep, we went beyond the round-circle focus group format and used tools such as prompt cards and drawing activities to allow each individual to fully express themselves.

The stories we heard added richness to our thinking we could never have achieved in isolation. So we listened and put pen to paper in order to really understand what’s working and what isn’t in the design of affordable housing. It was incredibly heartening to hear participants express how much it meant to have someone sit down and listen to their views.

While we don’t know who will live in Anne Street Garden Villas as yet, the opportunity to speak with tenants who have first-hand experience of social housing allowed us to better understand how their homes can better serve them.

WHAT YOU CAN LEARN FROM OUR FINDINGS

We are sharing the insights from these workshops in the hope they help to elevate other social housing projects around Australia.

There were many ideas shared in the workshops, which can be loosely categorised into these key themes:

Community: Car parking is a key consideration for social housing projects, but car parks often take up valuable space that could be used to encourage interaction between residents and bring people together. We were eager to find ways to address both of these concerns.

Privacy: While community interaction is important for mental health and feeling secure at home, residents also expressed the need for choice in how they engage with neighbours. Ideas suggested included visual privacy in their homes and private spaces for daily tasks (for example, not being forced to use shared laundry facilities).

Accessibility: Disabilities vary widely, and our workshops invited us to consider new ways for general social housing units to support the independence of a wider variety of people.

Adaptability: As society changes, it is vital that social housing does too. Themes including working from home and the changing demographics of social housing residents emerged in the workshop, allowing us to better understand how these homes will be used both now and into the future.

THE #1 LESSON WE LEARNED

When residents were asked to choose the qualities that would mean the most to them in a new development, there was a strong theme of connection with outdoors and the community.It emerged that in order for residents to feel a sense of belonging at home, they need to feel connected to their immediate surrounds and neighbours.

Following this workshop, we determined the primary challenge for this project: to devise practical ways of creating a village while supporting individual autonomy.

Our visit to existing social housing revealed that simple everyday pleasures – like a small garden with sunlight and drainage, or somewhere to host a barbecue – are lacking. These insights illustrate how social housing can become so much more than a roof and four walls when designed with people in mind (just as we would do in a private residential project).

We’re also thrilled that the success of these process means the Queensland Government is now in the process of establishing a panel of architects to conduct regular research and workshops with social housing tenants.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Naprostá

29.09.21 03:43

show all comments