Balloon Art Hall

"From the beginning, I felt that BEHF was really engaged with the project. Other architectural firms only showed us various UFOs." Alexander Munninger, client

"The only readable intervention from us is the inserted gallery. The only material we newly added to the building was concrete." Armin Ebner, architect

The remnants of former inner-city industrial buildings are not an unwelcome reference but rather an urban opportunity. London, for example, owes its new gallery Tate Modern to the brilliant combination of contemporary architecture and functionally-archaic industrial heritage (a former power plant). It is precisely in the peripheral districts, which city planners sometimes forget, that a whole inventory of industrial building stock awaits new functional use. A prime example of this international trend is the recent redevelopment of gasometers in Vienna’s Simmering. In the neighboring district of Vienna-Favoriten, nothing has happened in this regard for a long time. Yet, the tenth district of Vienna was, during its heyday, the industrial core of the city. Traces from this time can be found in the urban area around Quellenstrasse, Siccardsburggasse, and Buchengasse. The industrial complex of the former "Hugo Reinhold Gläser" factory, of which not much has survived, suggests that there must have been bustling activity there at the turn of the century.

When you look today at the facade of the factory at Quellenstrasse 149, you feel as if you are in another time – not in Vienna, but in Manchester. This complex with workshop halls, a blacksmith's shop, a boiler room, and a machine room, along with a residential building for the factory owner as well as other buildings, was built using decorative brick technology (the main part of the buildings on Quellenstrasse is attributed to architect Oskar Lasky Senior) in 1889. Less than two decades later, in 1906, an extension was added to the complex on Siccardburggasse, a production hall with a glass roof made of small panels. The investor of this industrial gem was Maximilian Luzzato from Trieste, who took over the entire "H.R. Gläser" facility and operated it as a machine engineering plant until his death in the 1930s. Today, almost a hundred years after its creation, it is possible to write a new chapter in the history of this industrial legacy, as the architects BEHF breathed new life into these brick walls during the reconstruction of the hall.

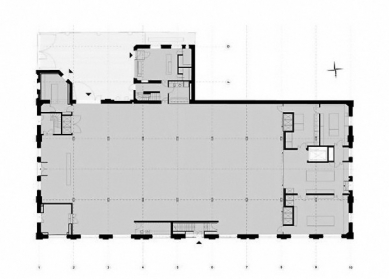

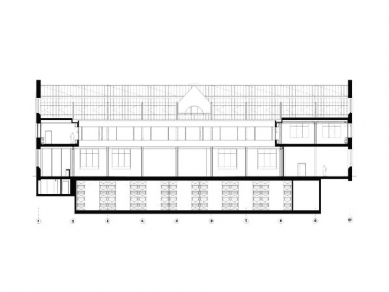

Despite it being a cold, gloomy November day, the hall gives off a friendly and light impression. Notable quality radiates from its walls and delicate iron structure. “For a hundred years, nothing has happened here,” recounts Alexander Munningen, the investor and owner of the company "balloonart", who wants to use the hall not only for offices, manufacturing, and storage but also as a community center. Many of the plans have previously faltered over a simple problem – heating costs. This covered, but essentially outdoor space is hard to heat to room temperature. The BEHF architects thus faced the complex task of maximizing the use of the hall while respecting the requirements of the Federal Monuments Office, under whose supervision the hall, as a monument, belongs. The problem was the roof's statics. The gallery that surrounds the hall consisted of slabs on a clay foundation. The redevelopment was therefore a risky challenge that required studying archival materials, as well as insights into current monument preservation technologies. The restoration was to include not only the creation of administrative and manufacturing spaces but also the establishment of an underground warehouse, without which the redevelopment would not make economic sense.

The BEHF architects approached their work with respect for the original building structure. In their understanding, “the old remains old and new building parts must be clearly recognizable.” No reconstruction, no false patina. To preserve the character of this old industrial cathedral, they retained traces of the old use as well as original color layers as much as possible. Where feasible, they kept the original windows, although in the offices, new windows took precedence over the old ones. They also preserved the original freight elevator, simply relocating it to its original position according to current safety regulations. To create an air-conditioned space for offices, BEHF opted for a "space within a space" concept. They enclosed the old open gallery with reinforced concrete prefabricated elements. This created a climatically separated building object that remains in constant visual contact with the hall. They thus preserved the former direct visual relationship between the offices in the gallery and the production hall. However, it no longer serves the factory owner to oversee his workers but instead to engage with visitors to the center. The BEHF architects utilize the principle of “non-hierarchical space” in designing the offices. Each department in the administrative gallery is therefore separated from each other only by flexible glass walls. Even though nearly a third of the gallery is currently unused, there are no plans to close any offices. On the contrary, a plan for their future use is being prepared in cooperation with the University of Vienna. However, it is primarily the details that affect the impression of this type of building: the iron beams are not replaced but simply painted with fire-resistant paint, the filigree structure of the roof is preserved, and the quality of the old walls is emphasized. In this way, the remnant of the industrial epoch embarks on a journey from forgotten past to an exciting future.

"The only readable intervention from us is the inserted gallery. The only material we newly added to the building was concrete." Armin Ebner, architect

The remnants of former inner-city industrial buildings are not an unwelcome reference but rather an urban opportunity. London, for example, owes its new gallery Tate Modern to the brilliant combination of contemporary architecture and functionally-archaic industrial heritage (a former power plant). It is precisely in the peripheral districts, which city planners sometimes forget, that a whole inventory of industrial building stock awaits new functional use. A prime example of this international trend is the recent redevelopment of gasometers in Vienna’s Simmering. In the neighboring district of Vienna-Favoriten, nothing has happened in this regard for a long time. Yet, the tenth district of Vienna was, during its heyday, the industrial core of the city. Traces from this time can be found in the urban area around Quellenstrasse, Siccardsburggasse, and Buchengasse. The industrial complex of the former "Hugo Reinhold Gläser" factory, of which not much has survived, suggests that there must have been bustling activity there at the turn of the century.

When you look today at the facade of the factory at Quellenstrasse 149, you feel as if you are in another time – not in Vienna, but in Manchester. This complex with workshop halls, a blacksmith's shop, a boiler room, and a machine room, along with a residential building for the factory owner as well as other buildings, was built using decorative brick technology (the main part of the buildings on Quellenstrasse is attributed to architect Oskar Lasky Senior) in 1889. Less than two decades later, in 1906, an extension was added to the complex on Siccardburggasse, a production hall with a glass roof made of small panels. The investor of this industrial gem was Maximilian Luzzato from Trieste, who took over the entire "H.R. Gläser" facility and operated it as a machine engineering plant until his death in the 1930s. Today, almost a hundred years after its creation, it is possible to write a new chapter in the history of this industrial legacy, as the architects BEHF breathed new life into these brick walls during the reconstruction of the hall.

Despite it being a cold, gloomy November day, the hall gives off a friendly and light impression. Notable quality radiates from its walls and delicate iron structure. “For a hundred years, nothing has happened here,” recounts Alexander Munningen, the investor and owner of the company "balloonart", who wants to use the hall not only for offices, manufacturing, and storage but also as a community center. Many of the plans have previously faltered over a simple problem – heating costs. This covered, but essentially outdoor space is hard to heat to room temperature. The BEHF architects thus faced the complex task of maximizing the use of the hall while respecting the requirements of the Federal Monuments Office, under whose supervision the hall, as a monument, belongs. The problem was the roof's statics. The gallery that surrounds the hall consisted of slabs on a clay foundation. The redevelopment was therefore a risky challenge that required studying archival materials, as well as insights into current monument preservation technologies. The restoration was to include not only the creation of administrative and manufacturing spaces but also the establishment of an underground warehouse, without which the redevelopment would not make economic sense.

The BEHF architects approached their work with respect for the original building structure. In their understanding, “the old remains old and new building parts must be clearly recognizable.” No reconstruction, no false patina. To preserve the character of this old industrial cathedral, they retained traces of the old use as well as original color layers as much as possible. Where feasible, they kept the original windows, although in the offices, new windows took precedence over the old ones. They also preserved the original freight elevator, simply relocating it to its original position according to current safety regulations. To create an air-conditioned space for offices, BEHF opted for a "space within a space" concept. They enclosed the old open gallery with reinforced concrete prefabricated elements. This created a climatically separated building object that remains in constant visual contact with the hall. They thus preserved the former direct visual relationship between the offices in the gallery and the production hall. However, it no longer serves the factory owner to oversee his workers but instead to engage with visitors to the center. The BEHF architects utilize the principle of “non-hierarchical space” in designing the offices. Each department in the administrative gallery is therefore separated from each other only by flexible glass walls. Even though nearly a third of the gallery is currently unused, there are no plans to close any offices. On the contrary, a plan for their future use is being prepared in cooperation with the University of Vienna. However, it is primarily the details that affect the impression of this type of building: the iron beams are not replaced but simply painted with fire-resistant paint, the filigree structure of the roof is preserved, and the quality of the old walls is emphasized. In this way, the remnant of the industrial epoch embarks on a journey from forgotten past to an exciting future.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment