Basilica di San Giorgio Maggiore

Church of the Monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore

This is a Renaissance-Baroque sacred building that is situated on an island in Italian Venice, which shares the same name. The present basilica became significant due to the arrival of the Benedictines in 982 and their leader Giovanni Morosini, who established a monastery on the island. Giovanni became the abbot of the monastery. It gradually became the most prominent Benedictine monastery in all of Italy. Nowadays, it serves as a pilgrimage site not only for the Venetians.

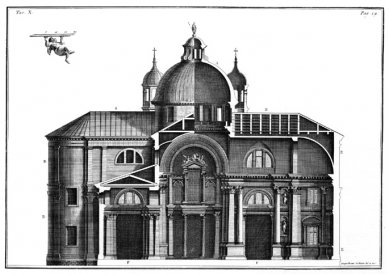

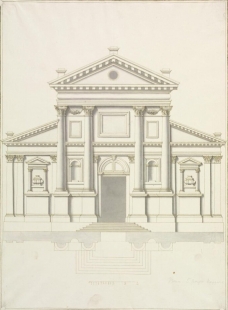

Due to a major earthquake that struck the island and caused enormous damage to numerous structures, including the church and the monastery in 1223, both buildings were rebuilt. Another significant reconstruction was commissioned to the already known Padua architect Andrea Palladio. This was his second commission for the Benedictine convent (the implementation of the report of the monastery took place in 1560-63). Palladio led the construction only until 1568, as his sudden death prevented him from completing it. However, the construction continued strictly according to Palladio's plan. The only difference is the facade built between 1607-10 under the guidance of the Vicenza architect Vicenza Scamozzi.

We can say that this is the first significant building of sacred character designed by Palladio. Together with other churches in Venice, such as the Church of the Redeemer, also designed by him, or Santa Maria della Salute, they form a trio of significantly placed buildings on the adjacent islands at the mouth of the Grand Canal. A characteristic feature of these works is the subordination of the visual effect.

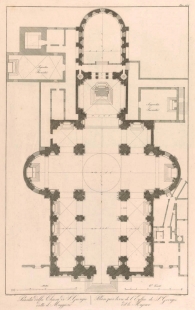

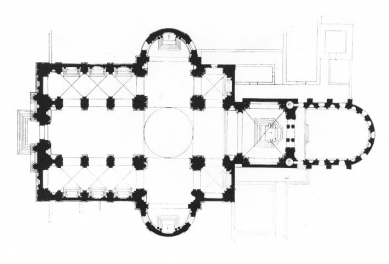

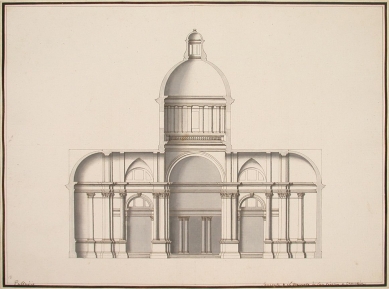

The facade of the temple is oriented towards St. Mark's Square, even though the church is separated from the main square by a water barrier. It thus creates a certain visual counterpoint to the core of Venice. It is a three-nave church standing on the floor plan of a Latin cross with a transept. The ceiling features a simple barrel vault. Part of the construction is a bell tower, interestingly, it is the 4th bell tower after the fall of the previous 3. The dominant facade of the church is made of Istrian marble.

The complex is situated at the traditional height of Venetian architecture near the water, fitting into the attractive surroundings of Venice.

The Fourth Book on the Architecture of Andrea Palladio

Preface to the Readers

If genuine effort and diligence are to be put into any building so that its arrangement has beautiful dimensions and proportions, it must, without any doubt, be especially true in the case of temples, in which we must honor the Creator and Giver of all things, the Best and Highest God, and therefore praise Him as much as our strength allows, and thank Him for all the benefactions He constantly bestows upon us. If, therefore, people in the construction of their own homes take the greatest care to find excellent and experienced architects and suitable craftsmen, they are certainly obliged to spend much more in building churches. And if they first consider mainly comfort, they must look at dignity and grandeur in the case of the latter, as it is to Him who is to be invoked and worshiped, who is the highest good and the highest perfection; thus, it is very appropriate that all that is dedicated to Him should be brought to the highest perfection of which we are capable. And indeed, if we observe this beautiful machine of the universe, how many admirable adornments it is filled with, and how the heavens move in it with their constant orbits, changing the seasons according to natural necessity, and with the sweetest harmony of their gentle motion preserve themselves, we cannot doubt that the small temples we build must be similar to this greatest one of His infinite kindness, which He accomplished perfectly with a single word, and therefore we cannot refrain from putting all those adornments that are available to us in them and from building them in such dimensions that all parts in the whole bring harmony to the eyes of the viewers, and that each one serves appropriately its intended purpose. Even though those who, led by the best intentions, have built and continue to build churches and temples to the Most High God are worthy of great praise, nonetheless, it seems impossible to leave them without a little reproach if they have not sought to make them in the best and most magnificent form that our conditions allow.

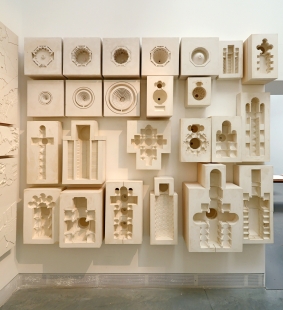

Thus, since the ancient Greeks and Romans have taken the utmost care in the construction of temples for their gods and provided them with the most beautiful architecture, to be created with the richest adornments and the best proportions, as is fitting for the god to whom they are dedicated, I wish in this book to show the forms and decorations of many ancient temples, of which some ruins can still be seen, which I have drawn, so that everyone can understand what forms and with what decorations churches should be built. And although in some of them only a small part is visible above the ground, I have nonetheless tried to deduce from this small part, having examined the foundations that could be seen, what they were like when they were whole. In doing so, I was greatly helped by Vitruvius, because when I compared what I saw with what he teaches, it was not too difficult for me to come to an understanding of their shape and form. But regarding the decorations, namely the bases, columns, capitals, entablatures, and similar things, I reported nothing of my own but measured them with the utmost attention to all fragments found in the places where these temples were located. And I have no doubt that those who will read this book and closely observe the drawings will be able to understand many passages that Vitruvius considers the most difficult and turn their thoughts to the knowledge of beautiful and proportionate forms of temples and draw from them many noble and diverse ideas, thus they will be able to show, in their appropriate use in their works, how it should and can change, without deviating from the rules of art, and how such changes are commendable and graceful. But before we move to the drawings, I will briefly state, as I am accustomed, those guidelines that must be observed when building temples, which I have also taken from Vitruvius and from many distinguished individuals who have written about this most noble art.

Chapter I.

On the Place to Be Chosen for Building Temples

Tuscany was not only the first to adopt foreign architecture in Italy, from which the order called Tuscan received its dimensions, but it was also a teacher to the surrounding nations regarding the gods that the majority of the world invoked in blind error, and it demonstrated what kinds of temples should be built, in what place, and with what adornments according to the characteristics of the gods; although many temples show that these guidelines were disregarded, I will briefly speak of them according to the records of the writers, so that those who enjoy antiquities may be satisfied in this respect and may the spirit of each be developed and ignited to exert every possible effort in building temples, for it is very bad and reprehensible that we, who have the true faith, are outdone in this by those who have not been enlightened by the truth. Since the places where holy temples should be situated are the first thing to be considered, I will speak of them in this first chapter. I therefore say that the ancient Tuscans prescribed that temples be built to Venus, Mars, and Vulcan outside the city, as they incited vice, warfare, and fires; and in the cities, they prescribed that temples be built to those who favored chastity, peace, and beautiful arts; and to those gods under whose protection the city was especially placed, and to Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, who were considered protectors of cities, temples were built on the highest places, in the middle of the territory and on rocks. And to Palladio, Mercury, and Isis, because they ruled over crafts and trade, temples were built near the squares and sometimes directly on the squares; to Apollo and Bacchus next to the theater; to Hercules near the circus and amphitheater; to Asklepios, Salus, and those gods from whose remedies many people believed they had been healed, temples were built at the most healthy places and near healing waters, so that the sick could be healed more quickly and with less difficulty by passing from bad and infected air to good and healthy and by drinking those waters, thus increasing religious fervor. And so they believed it fitting for other gods to find places for building their temples according to the qualities ascribed to them and according to the ways of their sacrifices. But we, who have been freed from these darknesses by the special grace of God and have abandoned their vain and false superstitions, will choose for temples those places that will be in the highest and most glorious part of the city, far from indecent places and in beautiful and adorned squares into which many streets lead, so that it is possible to see every part of the temple in its dignity, which will multiply the piety and admiration of everyone who sees and observes it. And if there are hills in the city, the highest part of them will be chosen. But if there are no elevated places, the level of the temple will be raised above the rest of the city as much as is appropriate, and access to the temple will be made by steps, as ascending to the temple carries with it greater piety and dignity. The fronts of the temples will be made so that they lead to the largest part of the city, so that it seems that religion has been established as if a guardian and protector of the townspeople. But if temples are to be erected outside the city, then their fronts will be made to lead to public roads or to rivers, if there is to be building near them, so that passersby can see and greet them and bow before the front of the temple.

Chapter II.

On the Shapes of Temples and the Proportionality That Must Be Observed In Them

Temples are constructed as round, quadrangular, six-sided, octagonal, and more polygonal shapes, all of which end in the outline of a circle, cross-shaped, and many other forms and designs that always deserve praise if they are distinguished by beautiful and appropriate proportions and graceful and adorned architecture. However, the most beautiful and most regular shapes, from which all others derive their measurements, are the round and quadrangular, and therefore only of these two does Vitruvius speak and teaches us how they should be proportioned, as will be said when it comes to the proportions of temples. For temples that are not round, it must be carefully observed so that all corners are the same, whether the temple has four or six or more corners and sides. The ancients took into account what is fitting for each of their gods not only in the choice of places where temples were to be built, as was said previously, but also in the choice of shapes, so that to the Sun and Moon, because they continuously circle around the world and through their orbits produce effects apparent to everyone, they made round temples or at least those that were close to being round; so also for Vesta, of whom they said she is the goddess of the Earth, of which element we know to be round. They made temples open to Jupiter as the protector of air and sky in the center, surrounded by a portico, as I will explain later. In the decorations, they paid great attention to whom they were building for, and thus for Minerva, Mars, and Hercules, they made Doric temples, because they said that for these gods it is fitting to have constructions without delicacy and gentleness given their warlike nature. But they said that temples for Venus, Flora, the Muses, and the nymphs and the most delicate goddesses should be built in a way that suits a flowering and tender maidenhood, hence they gave them the Corinthian order, as it seemed to them that for such an age delicate and blooming work, adorned with leaves and volutes, is appropriate. But for Juno, Diana, Bacchus, and other gods, since neither the weight of the former nor the gentleness of the latter seemed suitable for them, they attributed them the Ionic order, which occupies a middle ground between the Doric and Corinthian. Thus, we read that the ancients, in building temples, endeavored to maintain proportionality, in which the most beautiful part of architecture lies. And therefore, we too, who do not have false gods, will choose the most perfect and excellent shape among forms of temples for the preservation of proportionality; since a circle is such, because it is the only simple, uniform, equal, solid, and comprehensive shape among all forms, we will make round temples, to which this form is most suitable; because it is closed by a single boundary in which neither beginning nor end can be found, nor can one be distinguished from the other, as its parts are mutually similar and all partake in the form of the whole, and finally because in each of its parts the edge is equally distant from the center, it is most capable of demonstrating unity, endless being, uniformity, and the justice of God. Moreover, it cannot be denied that temples require more strength and stability than all other buildings, as they are dedicated to the Best and Highest God and preserve the most glorious and most dignified monuments of the city; thus also for this reason, it must be said that the circular form, in which there is no corner, is most suitable for temples. Temples must also be very capacious, so that many people can comfortably fit for divine services, and among all shapes that are enclosed by the same circumference, there is none more capacious than the round. Churches that are made in the shape of a cross are also highly commendable, which have the entrance on the side that would be the heel of the cross, and opposite the main altar and choir, and in the two arms that extend on both sides like arms, two further entrances or two additional altars, because in this shape of the cross they represent to the eyes of viewers that wood from which our salvation hung. And I made this shape for the church of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice.

Temples must have a wide portico with larger columns than those required by other buildings, and it is fitting that they be large and magnificent (but not larger than is required by the size of the city) and have large and beautiful proportions, as the divine cult for which they are made demands all sorts of magnificence and greatness. They must be created in the most beautiful columnar orders, and each order must be given its own and suitable adornments. They will be made from the best and most valuable materials so that form, decorations, and material honor the divinity as much as possible, and if possible, they must be made in such a way that they have such beauty that it would be impossible to imagine a thing more beautiful, and they must be arranged in all their parts so that those who enter stand amazed and with their spirits absorbed in contemplating their beauty and grace. Among all colors, none suits temples better than whiteness, as the purity of color and life is extremely dear to God. But if they are painted, the paintings that would detract the soul from contemplating divine matters will not fit well, as in temples we must not deviate from seriousness and from those things whose observation ignites our souls for service to God and for good deeds.

Chapter III.

On the Aspects of Temples

The aspect refers to the first impression that the temple itself gives to those who approach it. There are seven aspects of temples that are the most correct and most widespread, of which it seemed necessary for me to present what Vitruvius says about them in the first chapter of the first book so that this part, which many have considered difficult due to little attention to antiquity and which still few understand well, becomes easy and clear through what I shall say and the drawings that will follow, which will serve as examples of what he teaches; and I also wanted to use the names he uses so that those who will devote themselves to reading Vitruvius, and I urge everyone to do so, will recognize the same names in him and it will not seem to them that they are reading different matters. Thus, to get to our topic: temples are made either with a portico or without a portico. Those made without a portico can have three aspects: one is called in antis, that is, a facade in pilasters since antas are the pilasters that are made at the corners or edges of buildings. Of the other two, one is called prostylos, which means a facade in columns, and the other amfiprostylos. The one called in antis will have two pilasters at the edges, which also extend to the sides of the temple, and between these pilasters at the center of the front, there will be two columns extending forward and supporting the pediment that will be above the entrance. The second, which is called prostylos, will have, against the first, additionally columns also at the edges opposite the pilasters and one on each side at the edge transition. However, if the same arrangement of columns and pediment is maintained in the back, it will create an aspect known as amfiprostylos. Of the first two aspects of temples, we have no remains today, and therefore there will be no examples of them in this book. Nor did it seem necessary for me to make drawings for them, as plans and outlines for each of these aspects are depicted in Vitruvius and explained by the honorable Mr. Barbaro.

But if temples are given a portico, they are made either around the entire temple or only in the front. Of those that have a portico only on the front, one can say that they also have an aspect called prostylos. But those that are built with a surrounding portico can be made in four aspects, for they are made with six columns on the front and on the back facades and with eleven columns on the sides, including corner ones; this aspect is called perípteros, that is, winged around; the portico around the cell is then as wide as one intercolumnium. Old temples can be seen that have six columns on the facade, and yet do not have a portico around, but on the cell walls’ outer side, there are half-columns that accompany the portico columns and have the same decorations, as in Nîmes in Provence; one could say that this type was a temple of the Ionic order in Rome, which is now the Church of Santa Maria in Egypt. Architects did this to create a wider cell and to reduce costs while still maintaining the same aspect of the winged temple for those who saw the temple from the side. Or temples are given eight columns at the front and fifteen on the sides including the corners; then they have a double portico around, and therefore their aspect is called dípteros, that is, doubly winged. Or it is good to make temples that have, as the preceding ones, eight columns on the front and fifteen on the sides, but the portico is not made double, because one row of columns is removed, so the porticos are then as wide as two intercolumniums and one width of the column, and their aspect is called pseudodipteros, namely, the false doubly winged. This aspect was invented by Hermogenes, the oldest architect, who made the portico wide and comfortable around the temple in this way, to ease labor and costs while losing nothing of its appearance. Finally, temples are made so that there are ten columns on both fronts and a double portico around, like those that have the appearance of dípteros. These temples had additional porticos on the inner side with two rows of columns above each other, and these columns were smaller than the outer ones; the roof sloped from the outer columns to the inner ones, and the entire space surrounded by the inner columns was open, so the aspect of these temples was called hipaithros, namely, uncovered. These temples were dedicated to Jupiter as the protector of heaven and air; an altar was placed in the center of the courtyard. I believe that this aspect belonged to the temple whose certain slight remnants can be seen in Rome on Monte Cavallo and that it was dedicated to Jupiter Quirinus and built by the emperor, for in the time of Vitruvius (as he says) there was none.

Chapter IV.

On the Five Types of Temples

The ancients usually made (as was said before) porticos at their temples for the comfort of the people, so that they would have a place to linger and stroll outside the cell where the sacrifices were made, and to give these buildings more dignity. Therefore, there can be gaps between the columns in five sizes, by which Vitruvius distinguishes five types or methods of temples whose names are pyknostylos, that is, with dense columns, systylos with wider ones, diastylos with even more distant ones, araiostylos with columns spaced more than usual, and eustylos, which has reasonable and suitable gaps. What all these intercolumniations are and how they ought to relate to the length of the columns has been stated above in the first book, and drawings were provided, so I need not say anything more here except that the first four methods have deficiencies. The first two, because they have intercolumniations of one and a half diameter or two diameters of the columns, are very small and tight, so that two people cannot enter the portico simultaneously but must go in single file; the doors and their adornments cannot be seen from afar, and finally, the tightness of the spaces inhibits movement around the temple. Therefore, these two types are bearable if large columns are used, as can be seen in almost all ancient temples. In the third type, since three diameters of the column can be placed between the columns, the intercolumniations are very wide, causing the architraves to break due to the size of the spaces. However, this deficiency can be remedied by placing arches or curved beams above the architrave at the height of the frieze that support the load and leave the architrave free. The fourth type, even though it does not have the deficiencies of the preceding one since it does not use stone or marble architraves but lays wooden beams above the columns, can still be marked as deficient as it is low, wide, and compressed; and it is typical of the Tuscan order. The most beautiful and most graceful way of temple is the one called eustylos, which has intercolumniations of two and a quarter diameters of the column, thus it best serves utility, beauty, and strength. I have called the types of temples by the same names that Vitruvius gives them, as I did also with the aspects, both for the reasons mentioned above and also because these names appear already well established in our language and everyone understands them, and therefore I will also use them with the drawings of the temples that will follow.

Chapter V.

On the Proportions of Temples

Although in all buildings there is an effort for their parts to correspond with one another and to have such proportions that there is no single one that cannot be measured against the whole and other parts, this must be observed with especially extreme care in temples, as they are dedicated to divinity, for whose honor and devotion all must be executed in the most beautiful and most precious manner. Since the most common shapes of temples are round and quadrangular, I will say how each of them should be proportioned, and I will also mention something regarding the temples we Christians use. Round temples were once made either open, that is without a cell, with columns that supported the dome, as those dedicated to Juno Lacinia, in whose center an altar was placed, and on it a fire that was unquenchable. They are proportioned as follows: the diameter of the entire space that the temple is to occupy is divided into three equal parts; one of them is designated for the steps, that is, for the ascent to the level of the temple, and the other two remain for the temple and the columns that are built on the bases and are tall with a base and capital just as the diameter of the smaller circle of the steps and thick one-tenth of their height. The architrave, frieze, and other decorations are made according to what has been said in the first book regarding this as well as other types of temples. But those that are made closed, that is with a cell, are made either with wings around or with one portico only in the front. In those that are winged around, the proportions are as follows: two steps are first made all around and onto them are placed the bases on which columns stand; the wings are wide one-fifth of the diameter of the temple, taking the diameter from the inner side of the bases. The columns are as long as the width of the cell and thick one-tenth of their length. The tribune or dome is made high above the architrave, frieze, and the cornice of the wings as is half the entire building; thus Vitruvius divided round temples. However, in ancient temples, the bases are not seen, but the columns begin at the level of the temples, which I prefer much more, both because bases hinder greatly at the entrance to the temple and also because columns that start from the ground give more size and dignity. But if a single portico is given to the round temples at the front, it should be made long, as wide as the cell or less by one-eighth; it can be made even shorter, but never so that it is shorter than three-quarters of the width of the temple, and it should not be made wider than one-third of its length. In quadrangular temples, the porticoes in the front are made long as the width of these temples, and if they are made in the manner of eustylos, which is beautiful and graceful, they are divided so that if the front has four columns, the entire front of the temple is divided (with the exception of the projections of the bases of the columns that will be at the corners) into eleven and a half parts, one of which will be called a module, that is, the measure by which other parts will be measured, because if the columns are made thick one module, then they can be given to four columns, three to the middle intercolumnium, and four and a half to the other two intercolumniums, that is, two and a quarter to each; if the front has six columns, it will be divided into eighteen; if eight, then twenty-four and a half; and if ten, it will be divided into thirty-one, and one of these parts will always be given to the thickness of the columns, three to the middle space, and two and a quarter to each of the other spaces. The height of the columns will be made according to whether they are Ionic or Corinthian. How to fix the aspects of the other types of temples, that is, pyknostylos, systylos, diastylos, and araiostylos, has been fully stated in the first book when we discussed intercolumniations. Behind the portico lies the pronaos and then the cella. The width is divided into four parts, the length of the temple is made of eight, and five of those are given to the length of the cella including the walls where the doors are; and the remaining three remain for the pronaos, which has on both sides two wings of walls extending the walls of the cella, at the ends of which two antas, that is, two pilasters, as thick as the columns of the portico, are made, and since it may happen that there will be little or much space between these wings, then if the width is greater than twenty feet, two columns or more must be placed between those pilasters opposite the columns of the portico, according to what will demand necessity, whose task will be to separate the pronaos from the portico, and the three or more spaces that will be between the pillars will be closed with marble slabs or parapets, and openings will be left there through which one can enter the vestibule; if the width is greater than forty feet, it will be necessary to erect additional columns on the inner side against those placed between the pilasters, and they will be made as high as the outer ones, but somewhat thinner, because the open space will subtract from the thickness of the outer ones, and the closed space will not allow recognizing the slenderness of the inner ones, so they will appear the same. But although such a division comes out in temples with four columns, it does not result in the same ratio in other aspects and types since it is necessary for the walls of the cella to stand against the outer columns and be in one row so that the cella of such temples will be somewhat larger than the one mentioned. Thus the ancients divided their temples, as taught by Vitruvius, and demanded that a portico be made under which people could shelter from the sun, rain, hail, and snow during bad weather and linger there on sunny days until it was time for sacrifices; but we dispense with porticos around and build temples that closely resemble basilicas, in which, as has been said, a portico was constructed inside, just as we now do in temples; this is so because the first people who, enlightened by the truth, dedicated themselves to our religion customarily gathered in the private basilicas out of fear of pagans, and seeing then that this shape proved extremely convenient, as it was possible to very honorably place the altar in the location of the tribunal and the choir was then conveniently around the altar while the remainder was open for the people, they did not change it, and therefore when proportioning the wings that we make in churches, the guidelines mentioned when we discussed basilicas will be observed. To our churches, a place is attached, separated from the rest of the temple, which we call the sacristy, where priestly garments, vessels, and holy books and other things necessary for the divine service are kept, and where the priests dress; and next to it, towers are built where bells are hung, which are used only by Christians to call people to worship. Beside the temple, dwellings for priests are made, which must be comfortable, with spacious courtyards and beautiful gardens, and particularly, places for holy virgins must be secure, elevated, and far from the bustle and sight of people. And that is enough about proportionality, aspects, types, and the proportions of temples. Now I will present drawings of many ancient temples, while I will maintain this order: first, I will present drawings of those temples that are in Rome, then those that are outside Rome and in Italy, and finally those that are outside Italy. And for easier understanding, and to avoid the lengthiness and tedium that I might bring to readers if I were to give detailed dimensions of each part, I have marked them all with numbers in the drawings.

The Vicenza foot, by which all the following temples were measured, is on page 90 of the second book.

The whole foot is divided into ten degrees, and each inch into four minutes.

Palladio, Andrea. The Four Books on Architecture. Prague: SNKLHU, 1958, pp. 221-231

I quattro libri dell' architettura di Andrea Palladio, Venice, Appresso Dominico de' Franceschi, 1570

Due to a major earthquake that struck the island and caused enormous damage to numerous structures, including the church and the monastery in 1223, both buildings were rebuilt. Another significant reconstruction was commissioned to the already known Padua architect Andrea Palladio. This was his second commission for the Benedictine convent (the implementation of the report of the monastery took place in 1560-63). Palladio led the construction only until 1568, as his sudden death prevented him from completing it. However, the construction continued strictly according to Palladio's plan. The only difference is the facade built between 1607-10 under the guidance of the Vicenza architect Vicenza Scamozzi.

We can say that this is the first significant building of sacred character designed by Palladio. Together with other churches in Venice, such as the Church of the Redeemer, also designed by him, or Santa Maria della Salute, they form a trio of significantly placed buildings on the adjacent islands at the mouth of the Grand Canal. A characteristic feature of these works is the subordination of the visual effect.

The facade of the temple is oriented towards St. Mark's Square, even though the church is separated from the main square by a water barrier. It thus creates a certain visual counterpoint to the core of Venice. It is a three-nave church standing on the floor plan of a Latin cross with a transept. The ceiling features a simple barrel vault. Part of the construction is a bell tower, interestingly, it is the 4th bell tower after the fall of the previous 3. The dominant facade of the church is made of Istrian marble.

The complex is situated at the traditional height of Venetian architecture near the water, fitting into the attractive surroundings of Venice.

Roman Wintner

The Fourth Book on the Architecture of Andrea Palladio

Preface to the Readers

If genuine effort and diligence are to be put into any building so that its arrangement has beautiful dimensions and proportions, it must, without any doubt, be especially true in the case of temples, in which we must honor the Creator and Giver of all things, the Best and Highest God, and therefore praise Him as much as our strength allows, and thank Him for all the benefactions He constantly bestows upon us. If, therefore, people in the construction of their own homes take the greatest care to find excellent and experienced architects and suitable craftsmen, they are certainly obliged to spend much more in building churches. And if they first consider mainly comfort, they must look at dignity and grandeur in the case of the latter, as it is to Him who is to be invoked and worshiped, who is the highest good and the highest perfection; thus, it is very appropriate that all that is dedicated to Him should be brought to the highest perfection of which we are capable. And indeed, if we observe this beautiful machine of the universe, how many admirable adornments it is filled with, and how the heavens move in it with their constant orbits, changing the seasons according to natural necessity, and with the sweetest harmony of their gentle motion preserve themselves, we cannot doubt that the small temples we build must be similar to this greatest one of His infinite kindness, which He accomplished perfectly with a single word, and therefore we cannot refrain from putting all those adornments that are available to us in them and from building them in such dimensions that all parts in the whole bring harmony to the eyes of the viewers, and that each one serves appropriately its intended purpose. Even though those who, led by the best intentions, have built and continue to build churches and temples to the Most High God are worthy of great praise, nonetheless, it seems impossible to leave them without a little reproach if they have not sought to make them in the best and most magnificent form that our conditions allow.

Thus, since the ancient Greeks and Romans have taken the utmost care in the construction of temples for their gods and provided them with the most beautiful architecture, to be created with the richest adornments and the best proportions, as is fitting for the god to whom they are dedicated, I wish in this book to show the forms and decorations of many ancient temples, of which some ruins can still be seen, which I have drawn, so that everyone can understand what forms and with what decorations churches should be built. And although in some of them only a small part is visible above the ground, I have nonetheless tried to deduce from this small part, having examined the foundations that could be seen, what they were like when they were whole. In doing so, I was greatly helped by Vitruvius, because when I compared what I saw with what he teaches, it was not too difficult for me to come to an understanding of their shape and form. But regarding the decorations, namely the bases, columns, capitals, entablatures, and similar things, I reported nothing of my own but measured them with the utmost attention to all fragments found in the places where these temples were located. And I have no doubt that those who will read this book and closely observe the drawings will be able to understand many passages that Vitruvius considers the most difficult and turn their thoughts to the knowledge of beautiful and proportionate forms of temples and draw from them many noble and diverse ideas, thus they will be able to show, in their appropriate use in their works, how it should and can change, without deviating from the rules of art, and how such changes are commendable and graceful. But before we move to the drawings, I will briefly state, as I am accustomed, those guidelines that must be observed when building temples, which I have also taken from Vitruvius and from many distinguished individuals who have written about this most noble art.

Chapter I.

On the Place to Be Chosen for Building Temples

Tuscany was not only the first to adopt foreign architecture in Italy, from which the order called Tuscan received its dimensions, but it was also a teacher to the surrounding nations regarding the gods that the majority of the world invoked in blind error, and it demonstrated what kinds of temples should be built, in what place, and with what adornments according to the characteristics of the gods; although many temples show that these guidelines were disregarded, I will briefly speak of them according to the records of the writers, so that those who enjoy antiquities may be satisfied in this respect and may the spirit of each be developed and ignited to exert every possible effort in building temples, for it is very bad and reprehensible that we, who have the true faith, are outdone in this by those who have not been enlightened by the truth. Since the places where holy temples should be situated are the first thing to be considered, I will speak of them in this first chapter. I therefore say that the ancient Tuscans prescribed that temples be built to Venus, Mars, and Vulcan outside the city, as they incited vice, warfare, and fires; and in the cities, they prescribed that temples be built to those who favored chastity, peace, and beautiful arts; and to those gods under whose protection the city was especially placed, and to Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, who were considered protectors of cities, temples were built on the highest places, in the middle of the territory and on rocks. And to Palladio, Mercury, and Isis, because they ruled over crafts and trade, temples were built near the squares and sometimes directly on the squares; to Apollo and Bacchus next to the theater; to Hercules near the circus and amphitheater; to Asklepios, Salus, and those gods from whose remedies many people believed they had been healed, temples were built at the most healthy places and near healing waters, so that the sick could be healed more quickly and with less difficulty by passing from bad and infected air to good and healthy and by drinking those waters, thus increasing religious fervor. And so they believed it fitting for other gods to find places for building their temples according to the qualities ascribed to them and according to the ways of their sacrifices. But we, who have been freed from these darknesses by the special grace of God and have abandoned their vain and false superstitions, will choose for temples those places that will be in the highest and most glorious part of the city, far from indecent places and in beautiful and adorned squares into which many streets lead, so that it is possible to see every part of the temple in its dignity, which will multiply the piety and admiration of everyone who sees and observes it. And if there are hills in the city, the highest part of them will be chosen. But if there are no elevated places, the level of the temple will be raised above the rest of the city as much as is appropriate, and access to the temple will be made by steps, as ascending to the temple carries with it greater piety and dignity. The fronts of the temples will be made so that they lead to the largest part of the city, so that it seems that religion has been established as if a guardian and protector of the townspeople. But if temples are to be erected outside the city, then their fronts will be made to lead to public roads or to rivers, if there is to be building near them, so that passersby can see and greet them and bow before the front of the temple.

Chapter II.

On the Shapes of Temples and the Proportionality That Must Be Observed In Them

Temples are constructed as round, quadrangular, six-sided, octagonal, and more polygonal shapes, all of which end in the outline of a circle, cross-shaped, and many other forms and designs that always deserve praise if they are distinguished by beautiful and appropriate proportions and graceful and adorned architecture. However, the most beautiful and most regular shapes, from which all others derive their measurements, are the round and quadrangular, and therefore only of these two does Vitruvius speak and teaches us how they should be proportioned, as will be said when it comes to the proportions of temples. For temples that are not round, it must be carefully observed so that all corners are the same, whether the temple has four or six or more corners and sides. The ancients took into account what is fitting for each of their gods not only in the choice of places where temples were to be built, as was said previously, but also in the choice of shapes, so that to the Sun and Moon, because they continuously circle around the world and through their orbits produce effects apparent to everyone, they made round temples or at least those that were close to being round; so also for Vesta, of whom they said she is the goddess of the Earth, of which element we know to be round. They made temples open to Jupiter as the protector of air and sky in the center, surrounded by a portico, as I will explain later. In the decorations, they paid great attention to whom they were building for, and thus for Minerva, Mars, and Hercules, they made Doric temples, because they said that for these gods it is fitting to have constructions without delicacy and gentleness given their warlike nature. But they said that temples for Venus, Flora, the Muses, and the nymphs and the most delicate goddesses should be built in a way that suits a flowering and tender maidenhood, hence they gave them the Corinthian order, as it seemed to them that for such an age delicate and blooming work, adorned with leaves and volutes, is appropriate. But for Juno, Diana, Bacchus, and other gods, since neither the weight of the former nor the gentleness of the latter seemed suitable for them, they attributed them the Ionic order, which occupies a middle ground between the Doric and Corinthian. Thus, we read that the ancients, in building temples, endeavored to maintain proportionality, in which the most beautiful part of architecture lies. And therefore, we too, who do not have false gods, will choose the most perfect and excellent shape among forms of temples for the preservation of proportionality; since a circle is such, because it is the only simple, uniform, equal, solid, and comprehensive shape among all forms, we will make round temples, to which this form is most suitable; because it is closed by a single boundary in which neither beginning nor end can be found, nor can one be distinguished from the other, as its parts are mutually similar and all partake in the form of the whole, and finally because in each of its parts the edge is equally distant from the center, it is most capable of demonstrating unity, endless being, uniformity, and the justice of God. Moreover, it cannot be denied that temples require more strength and stability than all other buildings, as they are dedicated to the Best and Highest God and preserve the most glorious and most dignified monuments of the city; thus also for this reason, it must be said that the circular form, in which there is no corner, is most suitable for temples. Temples must also be very capacious, so that many people can comfortably fit for divine services, and among all shapes that are enclosed by the same circumference, there is none more capacious than the round. Churches that are made in the shape of a cross are also highly commendable, which have the entrance on the side that would be the heel of the cross, and opposite the main altar and choir, and in the two arms that extend on both sides like arms, two further entrances or two additional altars, because in this shape of the cross they represent to the eyes of viewers that wood from which our salvation hung. And I made this shape for the church of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice.

Temples must have a wide portico with larger columns than those required by other buildings, and it is fitting that they be large and magnificent (but not larger than is required by the size of the city) and have large and beautiful proportions, as the divine cult for which they are made demands all sorts of magnificence and greatness. They must be created in the most beautiful columnar orders, and each order must be given its own and suitable adornments. They will be made from the best and most valuable materials so that form, decorations, and material honor the divinity as much as possible, and if possible, they must be made in such a way that they have such beauty that it would be impossible to imagine a thing more beautiful, and they must be arranged in all their parts so that those who enter stand amazed and with their spirits absorbed in contemplating their beauty and grace. Among all colors, none suits temples better than whiteness, as the purity of color and life is extremely dear to God. But if they are painted, the paintings that would detract the soul from contemplating divine matters will not fit well, as in temples we must not deviate from seriousness and from those things whose observation ignites our souls for service to God and for good deeds.

Chapter III.

On the Aspects of Temples

The aspect refers to the first impression that the temple itself gives to those who approach it. There are seven aspects of temples that are the most correct and most widespread, of which it seemed necessary for me to present what Vitruvius says about them in the first chapter of the first book so that this part, which many have considered difficult due to little attention to antiquity and which still few understand well, becomes easy and clear through what I shall say and the drawings that will follow, which will serve as examples of what he teaches; and I also wanted to use the names he uses so that those who will devote themselves to reading Vitruvius, and I urge everyone to do so, will recognize the same names in him and it will not seem to them that they are reading different matters. Thus, to get to our topic: temples are made either with a portico or without a portico. Those made without a portico can have three aspects: one is called in antis, that is, a facade in pilasters since antas are the pilasters that are made at the corners or edges of buildings. Of the other two, one is called prostylos, which means a facade in columns, and the other amfiprostylos. The one called in antis will have two pilasters at the edges, which also extend to the sides of the temple, and between these pilasters at the center of the front, there will be two columns extending forward and supporting the pediment that will be above the entrance. The second, which is called prostylos, will have, against the first, additionally columns also at the edges opposite the pilasters and one on each side at the edge transition. However, if the same arrangement of columns and pediment is maintained in the back, it will create an aspect known as amfiprostylos. Of the first two aspects of temples, we have no remains today, and therefore there will be no examples of them in this book. Nor did it seem necessary for me to make drawings for them, as plans and outlines for each of these aspects are depicted in Vitruvius and explained by the honorable Mr. Barbaro.

But if temples are given a portico, they are made either around the entire temple or only in the front. Of those that have a portico only on the front, one can say that they also have an aspect called prostylos. But those that are built with a surrounding portico can be made in four aspects, for they are made with six columns on the front and on the back facades and with eleven columns on the sides, including corner ones; this aspect is called perípteros, that is, winged around; the portico around the cell is then as wide as one intercolumnium. Old temples can be seen that have six columns on the facade, and yet do not have a portico around, but on the cell walls’ outer side, there are half-columns that accompany the portico columns and have the same decorations, as in Nîmes in Provence; one could say that this type was a temple of the Ionic order in Rome, which is now the Church of Santa Maria in Egypt. Architects did this to create a wider cell and to reduce costs while still maintaining the same aspect of the winged temple for those who saw the temple from the side. Or temples are given eight columns at the front and fifteen on the sides including the corners; then they have a double portico around, and therefore their aspect is called dípteros, that is, doubly winged. Or it is good to make temples that have, as the preceding ones, eight columns on the front and fifteen on the sides, but the portico is not made double, because one row of columns is removed, so the porticos are then as wide as two intercolumniums and one width of the column, and their aspect is called pseudodipteros, namely, the false doubly winged. This aspect was invented by Hermogenes, the oldest architect, who made the portico wide and comfortable around the temple in this way, to ease labor and costs while losing nothing of its appearance. Finally, temples are made so that there are ten columns on both fronts and a double portico around, like those that have the appearance of dípteros. These temples had additional porticos on the inner side with two rows of columns above each other, and these columns were smaller than the outer ones; the roof sloped from the outer columns to the inner ones, and the entire space surrounded by the inner columns was open, so the aspect of these temples was called hipaithros, namely, uncovered. These temples were dedicated to Jupiter as the protector of heaven and air; an altar was placed in the center of the courtyard. I believe that this aspect belonged to the temple whose certain slight remnants can be seen in Rome on Monte Cavallo and that it was dedicated to Jupiter Quirinus and built by the emperor, for in the time of Vitruvius (as he says) there was none.

Chapter IV.

On the Five Types of Temples

The ancients usually made (as was said before) porticos at their temples for the comfort of the people, so that they would have a place to linger and stroll outside the cell where the sacrifices were made, and to give these buildings more dignity. Therefore, there can be gaps between the columns in five sizes, by which Vitruvius distinguishes five types or methods of temples whose names are pyknostylos, that is, with dense columns, systylos with wider ones, diastylos with even more distant ones, araiostylos with columns spaced more than usual, and eustylos, which has reasonable and suitable gaps. What all these intercolumniations are and how they ought to relate to the length of the columns has been stated above in the first book, and drawings were provided, so I need not say anything more here except that the first four methods have deficiencies. The first two, because they have intercolumniations of one and a half diameter or two diameters of the columns, are very small and tight, so that two people cannot enter the portico simultaneously but must go in single file; the doors and their adornments cannot be seen from afar, and finally, the tightness of the spaces inhibits movement around the temple. Therefore, these two types are bearable if large columns are used, as can be seen in almost all ancient temples. In the third type, since three diameters of the column can be placed between the columns, the intercolumniations are very wide, causing the architraves to break due to the size of the spaces. However, this deficiency can be remedied by placing arches or curved beams above the architrave at the height of the frieze that support the load and leave the architrave free. The fourth type, even though it does not have the deficiencies of the preceding one since it does not use stone or marble architraves but lays wooden beams above the columns, can still be marked as deficient as it is low, wide, and compressed; and it is typical of the Tuscan order. The most beautiful and most graceful way of temple is the one called eustylos, which has intercolumniations of two and a quarter diameters of the column, thus it best serves utility, beauty, and strength. I have called the types of temples by the same names that Vitruvius gives them, as I did also with the aspects, both for the reasons mentioned above and also because these names appear already well established in our language and everyone understands them, and therefore I will also use them with the drawings of the temples that will follow.

Chapter V.

On the Proportions of Temples

Although in all buildings there is an effort for their parts to correspond with one another and to have such proportions that there is no single one that cannot be measured against the whole and other parts, this must be observed with especially extreme care in temples, as they are dedicated to divinity, for whose honor and devotion all must be executed in the most beautiful and most precious manner. Since the most common shapes of temples are round and quadrangular, I will say how each of them should be proportioned, and I will also mention something regarding the temples we Christians use. Round temples were once made either open, that is without a cell, with columns that supported the dome, as those dedicated to Juno Lacinia, in whose center an altar was placed, and on it a fire that was unquenchable. They are proportioned as follows: the diameter of the entire space that the temple is to occupy is divided into three equal parts; one of them is designated for the steps, that is, for the ascent to the level of the temple, and the other two remain for the temple and the columns that are built on the bases and are tall with a base and capital just as the diameter of the smaller circle of the steps and thick one-tenth of their height. The architrave, frieze, and other decorations are made according to what has been said in the first book regarding this as well as other types of temples. But those that are made closed, that is with a cell, are made either with wings around or with one portico only in the front. In those that are winged around, the proportions are as follows: two steps are first made all around and onto them are placed the bases on which columns stand; the wings are wide one-fifth of the diameter of the temple, taking the diameter from the inner side of the bases. The columns are as long as the width of the cell and thick one-tenth of their length. The tribune or dome is made high above the architrave, frieze, and the cornice of the wings as is half the entire building; thus Vitruvius divided round temples. However, in ancient temples, the bases are not seen, but the columns begin at the level of the temples, which I prefer much more, both because bases hinder greatly at the entrance to the temple and also because columns that start from the ground give more size and dignity. But if a single portico is given to the round temples at the front, it should be made long, as wide as the cell or less by one-eighth; it can be made even shorter, but never so that it is shorter than three-quarters of the width of the temple, and it should not be made wider than one-third of its length. In quadrangular temples, the porticoes in the front are made long as the width of these temples, and if they are made in the manner of eustylos, which is beautiful and graceful, they are divided so that if the front has four columns, the entire front of the temple is divided (with the exception of the projections of the bases of the columns that will be at the corners) into eleven and a half parts, one of which will be called a module, that is, the measure by which other parts will be measured, because if the columns are made thick one module, then they can be given to four columns, three to the middle intercolumnium, and four and a half to the other two intercolumniums, that is, two and a quarter to each; if the front has six columns, it will be divided into eighteen; if eight, then twenty-four and a half; and if ten, it will be divided into thirty-one, and one of these parts will always be given to the thickness of the columns, three to the middle space, and two and a quarter to each of the other spaces. The height of the columns will be made according to whether they are Ionic or Corinthian. How to fix the aspects of the other types of temples, that is, pyknostylos, systylos, diastylos, and araiostylos, has been fully stated in the first book when we discussed intercolumniations. Behind the portico lies the pronaos and then the cella. The width is divided into four parts, the length of the temple is made of eight, and five of those are given to the length of the cella including the walls where the doors are; and the remaining three remain for the pronaos, which has on both sides two wings of walls extending the walls of the cella, at the ends of which two antas, that is, two pilasters, as thick as the columns of the portico, are made, and since it may happen that there will be little or much space between these wings, then if the width is greater than twenty feet, two columns or more must be placed between those pilasters opposite the columns of the portico, according to what will demand necessity, whose task will be to separate the pronaos from the portico, and the three or more spaces that will be between the pillars will be closed with marble slabs or parapets, and openings will be left there through which one can enter the vestibule; if the width is greater than forty feet, it will be necessary to erect additional columns on the inner side against those placed between the pilasters, and they will be made as high as the outer ones, but somewhat thinner, because the open space will subtract from the thickness of the outer ones, and the closed space will not allow recognizing the slenderness of the inner ones, so they will appear the same. But although such a division comes out in temples with four columns, it does not result in the same ratio in other aspects and types since it is necessary for the walls of the cella to stand against the outer columns and be in one row so that the cella of such temples will be somewhat larger than the one mentioned. Thus the ancients divided their temples, as taught by Vitruvius, and demanded that a portico be made under which people could shelter from the sun, rain, hail, and snow during bad weather and linger there on sunny days until it was time for sacrifices; but we dispense with porticos around and build temples that closely resemble basilicas, in which, as has been said, a portico was constructed inside, just as we now do in temples; this is so because the first people who, enlightened by the truth, dedicated themselves to our religion customarily gathered in the private basilicas out of fear of pagans, and seeing then that this shape proved extremely convenient, as it was possible to very honorably place the altar in the location of the tribunal and the choir was then conveniently around the altar while the remainder was open for the people, they did not change it, and therefore when proportioning the wings that we make in churches, the guidelines mentioned when we discussed basilicas will be observed. To our churches, a place is attached, separated from the rest of the temple, which we call the sacristy, where priestly garments, vessels, and holy books and other things necessary for the divine service are kept, and where the priests dress; and next to it, towers are built where bells are hung, which are used only by Christians to call people to worship. Beside the temple, dwellings for priests are made, which must be comfortable, with spacious courtyards and beautiful gardens, and particularly, places for holy virgins must be secure, elevated, and far from the bustle and sight of people. And that is enough about proportionality, aspects, types, and the proportions of temples. Now I will present drawings of many ancient temples, while I will maintain this order: first, I will present drawings of those temples that are in Rome, then those that are outside Rome and in Italy, and finally those that are outside Italy. And for easier understanding, and to avoid the lengthiness and tedium that I might bring to readers if I were to give detailed dimensions of each part, I have marked them all with numbers in the drawings.

The Vicenza foot, by which all the following temples were measured, is on page 90 of the second book.

The whole foot is divided into ten degrees, and each inch into four minutes.

Palladio, Andrea. The Four Books on Architecture. Prague: SNKLHU, 1958, pp. 221-231

I quattro libri dell' architettura di Andrea Palladio, Venice, Appresso Dominico de' Franceschi, 1570

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment