Malaparte House

Casa Malaparte

"The day I decided to build this house, I did not believe that this house would ultimately say more about me than my entire literary work."

Since 1922, the entire territory of the island of Capri has been declared a nature reserve under the management of a regulatory commission, and construction was not permitted here. However, the writer Curzio Malaparte (1898-1957), sent by Mussolini’s officials into “exile on the island of Lipari” (for the book Don Chameleon from 1928 and for The Technique of the Coup d'État from 1931 parodying the dictator), applied for a building permit to construct his house. He did not like Lipari, so he purchased Cap Massullo on the island of Capri, where he intended to build his new house. The building law established an absolute ban on construction in the Matromania area on the southern coast of Capri. Nevertheless, Malaparte submitted a building permit application on March 14, 1938, to the local authority, accompanied by the architectural documentation from architect Adalberto Libera (1903-1963), then an established official architect working in the spirit of Italian rationalism. Apparently, this circumstance led Minister Giuseppe Bottai to approve the construction of the house on Cap Massullo just two months later, described by Libera as a small weekend house - la Villetu. In September 1938, the conservation regime provisions in the area were revoked, thus nothing stood in the way of granting permission for the construction of Casa Malaparte on Cape Massullo on the southern coast of the island of Capri.

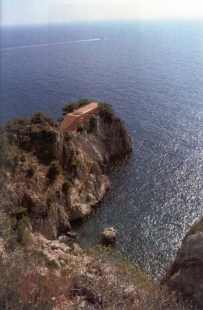

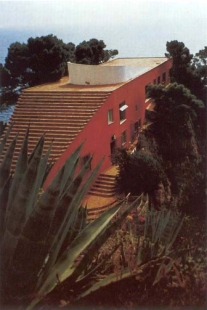

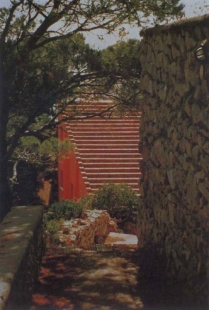

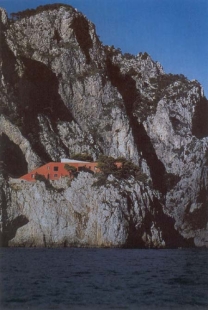

Several circumstances surrounding this extraordinarily impressive building are worth noting. Firstly, the circumstances of its inception. Adalberto Libera proposed a completely different concept than how the villa was ultimately realized. The architect, who incidentally never visited the construction site, designed a mass concept as a massive stone base with a lighter superstructure of living spaces. The builder Curzio Malaparte revised the design into a completely different form, where the central motif became a staircase with thirty-two steps smoothly connecting to the existing terrain and rising to the terrace of the house. Art historians believe that this idea is derived from Malaparte's visit to the church of Santa Annunziata on the island of Lipari, where he stayed during his exile. The photographic documentation is clear, yet the author’s own contribution remains a matter of speculation. It is particularly piquant that the writer bequeathed the villa to the Chinese communists, who showed no interest in it; thus it eventually became the property of relatives, who surrounded it with several barbed wire enclosures, though this did not significantly deter the interest of the architectural public.

The villa-legend is shrouded in many myths: one of the most famous is the conversation between Malaparte and Field Marshal Rommel, who spent his vacation here during the military campaign in North Africa. When asked by the marshal whether it (the villa) was already here or whether he (Malaparte) built it, the writer replied that it (the villa) was already here, and that he only designed what was around it. It is indisputable that the house's uniqueness is undoubtedly influenced by its extraordinary natural surroundings. As Kenneth Frampton and Vladimír Šlapeta say, this house is one of the most amazing works of Mediterranean architecture. Malaparte wanted a modern house, did not want any historical reminiscences, no columns or arches; he wanted a manifesto of modern architecture, which he paradoxically achieved. The actual object does not exhibit too much modernity; the terrace with a white, organically shaped wall on the roof is closest to the principles of modern architecture. For people living in the Central European region, it is unbelievable that the villa was built by the writer during his exile from 1938 to 1940. Art historians today try to define the object in some way and find connections with the past; for example, they compare the staircase motif to an ancient amphitheater, etc. However, the originality of the solution is unparalleled. The spatial concept is relatively banal; perhaps only the writer's room in the end position with a bedroom overlooking the endless horizon of the sea is worth mentioning.

Curzio Malaparte (*1898 Prato - +1957 Rome), born Kurt Sucker, was a controversial figure in Italian culture. In 1914, he voluntarily enlisted in the war, in 1918 he was awarded the French War Cross and a medal for bravery, from 1921 he directed the magazine La Stampa, and in 1931 he published in France The Technique of the Coup d'État, in which he parodied Mussolini's rise to power. He was subsequently arrested and deported to the island of Lipari and then to the island of Capri, after which he served as a correspondent for Corriere della Sera in Ethiopia. In 1940, he was a correspondent from the Russian front, then on the Finnish front, where he wrote Kaput (1944), and dealt with his experiences from the liberation of Italy by Anglo-American forces in the controversial novel The Skin (1949).

Curzio Malaparte

Since 1922, the entire territory of the island of Capri has been declared a nature reserve under the management of a regulatory commission, and construction was not permitted here. However, the writer Curzio Malaparte (1898-1957), sent by Mussolini’s officials into “exile on the island of Lipari” (for the book Don Chameleon from 1928 and for The Technique of the Coup d'État from 1931 parodying the dictator), applied for a building permit to construct his house. He did not like Lipari, so he purchased Cap Massullo on the island of Capri, where he intended to build his new house. The building law established an absolute ban on construction in the Matromania area on the southern coast of Capri. Nevertheless, Malaparte submitted a building permit application on March 14, 1938, to the local authority, accompanied by the architectural documentation from architect Adalberto Libera (1903-1963), then an established official architect working in the spirit of Italian rationalism. Apparently, this circumstance led Minister Giuseppe Bottai to approve the construction of the house on Cap Massullo just two months later, described by Libera as a small weekend house - la Villetu. In September 1938, the conservation regime provisions in the area were revoked, thus nothing stood in the way of granting permission for the construction of Casa Malaparte on Cape Massullo on the southern coast of the island of Capri.

Several circumstances surrounding this extraordinarily impressive building are worth noting. Firstly, the circumstances of its inception. Adalberto Libera proposed a completely different concept than how the villa was ultimately realized. The architect, who incidentally never visited the construction site, designed a mass concept as a massive stone base with a lighter superstructure of living spaces. The builder Curzio Malaparte revised the design into a completely different form, where the central motif became a staircase with thirty-two steps smoothly connecting to the existing terrain and rising to the terrace of the house. Art historians believe that this idea is derived from Malaparte's visit to the church of Santa Annunziata on the island of Lipari, where he stayed during his exile. The photographic documentation is clear, yet the author’s own contribution remains a matter of speculation. It is particularly piquant that the writer bequeathed the villa to the Chinese communists, who showed no interest in it; thus it eventually became the property of relatives, who surrounded it with several barbed wire enclosures, though this did not significantly deter the interest of the architectural public.

The villa-legend is shrouded in many myths: one of the most famous is the conversation between Malaparte and Field Marshal Rommel, who spent his vacation here during the military campaign in North Africa. When asked by the marshal whether it (the villa) was already here or whether he (Malaparte) built it, the writer replied that it (the villa) was already here, and that he only designed what was around it. It is indisputable that the house's uniqueness is undoubtedly influenced by its extraordinary natural surroundings. As Kenneth Frampton and Vladimír Šlapeta say, this house is one of the most amazing works of Mediterranean architecture. Malaparte wanted a modern house, did not want any historical reminiscences, no columns or arches; he wanted a manifesto of modern architecture, which he paradoxically achieved. The actual object does not exhibit too much modernity; the terrace with a white, organically shaped wall on the roof is closest to the principles of modern architecture. For people living in the Central European region, it is unbelievable that the villa was built by the writer during his exile from 1938 to 1940. Art historians today try to define the object in some way and find connections with the past; for example, they compare the staircase motif to an ancient amphitheater, etc. However, the originality of the solution is unparalleled. The spatial concept is relatively banal; perhaps only the writer's room in the end position with a bedroom overlooking the endless horizon of the sea is worth mentioning.

Curzio Malaparte (*1898 Prato - +1957 Rome), born Kurt Sucker, was a controversial figure in Italian culture. In 1914, he voluntarily enlisted in the war, in 1918 he was awarded the French War Cross and a medal for bravery, from 1921 he directed the magazine La Stampa, and in 1931 he published in France The Technique of the Coup d'État, in which he parodied Mussolini's rise to power. He was subsequently arrested and deported to the island of Lipari and then to the island of Capri, after which he served as a correspondent for Corriere della Sera in Ethiopia. In 1940, he was a correspondent from the Russian front, then on the Finnish front, where he wrote Kaput (1944), and dealt with his experiences from the liberation of Italy by Anglo-American forces in the controversial novel The Skin (1949).

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

5 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

casa malaparte ve filmu

de.ardoise

06.10.05 06:05

dotaz

matej.z

29.12.05 01:33

Monografie

Jan Kratochvíl

29.12.05 01:46

Půdorysy a řez vyšly v "Architektovi" č. 7 z roku 1999

šakal

29.12.05 11:23

navsteva vily

vt

14.07.14 01:09

show all comments