Temple of Pomona on Pfingstberg Hill

Pomonatempel Pentecost Mountain

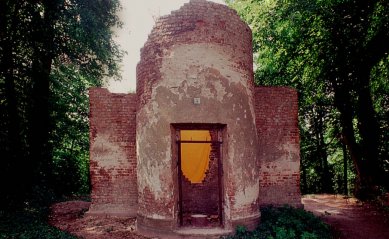

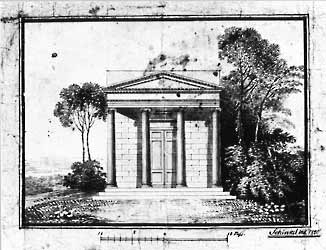

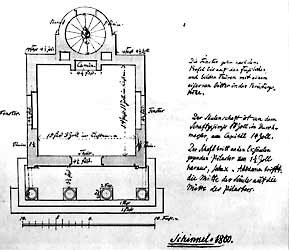

Karl Friedrich Schinkel was not only a gifted draftsman in his youth, but also a determined student who had a desire to gain knowledge from the best in the field. At the age of sixteen, Schinkel was inspired by the monument project for Emperor Frederick the Great by the young architect Friedrich Gilly, whose promising future was shaped by his father David Gilly, cut short in 1800 by tuberculosis. At the age of nineteen, Schinkel began studying at the newly established Academy of Architecture, where twenty-six-year-old Friedrich Gilly was a professor. They worked together on commissions, which Schinkel took over after Gilly's death. Schinkel completed his first realization at the age of twenty. It was the Pomona Temple on Pfingstberg Hill (Pentecost Mountain) near Potsdam. The romantic pavilion dedicated to the ancient goddess of fruit was primarily intended to test Schinkel's skills before he was later assigned larger royal commissions. Schinkel's plastered building, featuring four wooden Ionic columns in the façade, closely resembles the stone tomb of the von Hoym family (1800-02) in Brzeg Dolny near Wrocław, Poland, which is the only surviving work of Gilly, but the main precedent was, of course, the northern façade of the Erechtheion on the Athenian Acropolis.

The commission was entrusted to both young architects by the secret royal councilor Carl Ludwig von Oesfeld (1741-1804), who desired a tea pavilion to be designed on his vast vineyard (the hill was previously named Weinberg - Vineyard) as a gift for his wife. The blue and white canvas tent on the roof was added many years later so that social events could take place here in line with the customs of the time. In 1817, King Frederick William III purchased the vineyard, whose successor began to build a significantly larger Belvedere against the backdrop of the Pomona pavilion after Schinkel's death, designed by Schinkel's students from the Berlin Academy of Architecture, Ludwig Persius and Friedrich Stüler. Schinkel's pavilion was originally to be demolished to be replaced by hanging gardens, wide staircases, and water cascades in front of the Belvedere. However, King Frederick William IV did not live to see the completion. His successor, William I of Prussia, significantly reduced the ambitious plans and entrusted the completion to the famous landscape architect Peter Joseph Lenné, who harmoniously incorporated Schinkel's pavilion into his design and connected it to the disproportionately larger Belvedere with a semicircular living arcade, thus compensating for the asymmetrical placement of both buildings.

The first major reconstruction of the pavilion took place in the mid-1930s, with the approaching date of the summer Olympics in Berlin. Subsequently, World War II broke out, during which the historic center of Potsdam was damaged, but both structures on the strategically significant Pfingstberg hill survived relatively unscathed. They fell into greater disrepair, however, as they became part of a closed Soviet military area. While the St. Nicholas Church (1830-50) in the center of Potsdam was surrounded by a panel housing estate, the Pomona Temple and Belvedere above the city sadly deteriorated for several decades. It was not until the end of the 1980s that the park was reopened to the public, and the pavilion underwent a transformation only after the reunification of Germany, when from 1992 to 1993, the Hamburg foundation Hermann Reemtsma supported the total reconstruction of Schinkel's first realization with a sum of half a million marks. Two decades later (April 2011), the interior decoration of the tea pavilion was also addressed. The wall frescoes in blue shades by the Berlin painter Elisabeth Sonneck carry the title Temperaturen in Schinkels Blau (Temperatures in Schinkel's Blue). The complete reconstruction of the Belvedere was completed in 2003. The pavilion is now part of the gardens and palace complex in Potsdam, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The commission was entrusted to both young architects by the secret royal councilor Carl Ludwig von Oesfeld (1741-1804), who desired a tea pavilion to be designed on his vast vineyard (the hill was previously named Weinberg - Vineyard) as a gift for his wife. The blue and white canvas tent on the roof was added many years later so that social events could take place here in line with the customs of the time. In 1817, King Frederick William III purchased the vineyard, whose successor began to build a significantly larger Belvedere against the backdrop of the Pomona pavilion after Schinkel's death, designed by Schinkel's students from the Berlin Academy of Architecture, Ludwig Persius and Friedrich Stüler. Schinkel's pavilion was originally to be demolished to be replaced by hanging gardens, wide staircases, and water cascades in front of the Belvedere. However, King Frederick William IV did not live to see the completion. His successor, William I of Prussia, significantly reduced the ambitious plans and entrusted the completion to the famous landscape architect Peter Joseph Lenné, who harmoniously incorporated Schinkel's pavilion into his design and connected it to the disproportionately larger Belvedere with a semicircular living arcade, thus compensating for the asymmetrical placement of both buildings.

The first major reconstruction of the pavilion took place in the mid-1930s, with the approaching date of the summer Olympics in Berlin. Subsequently, World War II broke out, during which the historic center of Potsdam was damaged, but both structures on the strategically significant Pfingstberg hill survived relatively unscathed. They fell into greater disrepair, however, as they became part of a closed Soviet military area. While the St. Nicholas Church (1830-50) in the center of Potsdam was surrounded by a panel housing estate, the Pomona Temple and Belvedere above the city sadly deteriorated for several decades. It was not until the end of the 1980s that the park was reopened to the public, and the pavilion underwent a transformation only after the reunification of Germany, when from 1992 to 1993, the Hamburg foundation Hermann Reemtsma supported the total reconstruction of Schinkel's first realization with a sum of half a million marks. Two decades later (April 2011), the interior decoration of the tea pavilion was also addressed. The wall frescoes in blue shades by the Berlin painter Elisabeth Sonneck carry the title Temperaturen in Schinkels Blau (Temperatures in Schinkel's Blue). The complete reconstruction of the Belvedere was completed in 2003. The pavilion is now part of the gardens and palace complex in Potsdam, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Co to je "Pomon"?

Jan Ctibor

09.01.20 12:47

show all comments