House Dejardin-Hendricé

Experimental House of Steel

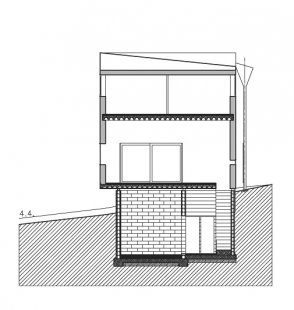

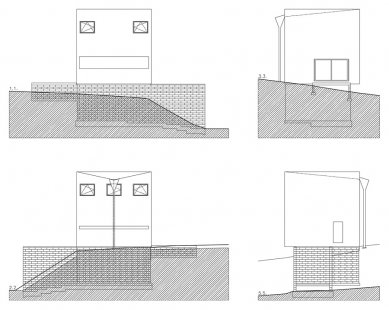

The house appears as a foreign body. Depending on whether the facades are dry or wet, it is rusty red or rusty brown. The two-story cube made of corten steel is situated in a quiet small village south of Liège. It is surrounded by traditional ochre cottages made from local limestone. It overlooks a meandering gently flowing river on the opposite side of the valley with forested hilltops. Nothing has been done to mitigate this sharp contrast. The house creates the impression that it has merely been placed here; for an indefinite period. It barely touches the ground, as if it needed to be quickly restored: an old retaining wall still holds the slope, and ivy-covered steps lead from the road to the upper meadow – the treatment of this dilapidated state vaguely resembles the then Upper Lawn Pavilion (a family house in Wiltshire from 1961) of the Smithsons. The only obvious surgical intervention in the terrain is two walls made of hollow concrete blocks running parallel. These walls slowly sink into the slope, upon which the cube of the house rests. The gap between the walls is chosen such that a protected entrance zone is created, which can also serve for parking a car.

The House as a Ship

Modern houses seem as if they are «prepared for travel», Ernst Bloch argued in his book «The Principle of Hope» (1959), and, like ships, they have a «taste for disappearance». Already in «The Heritage of This Time» (1935), there is a short excerpt on the topic of «houseboats» with the following sentences: «This house also no longer pretends to take root. [...] External stairs, riveted round windows only strengthen the impression that the house has become a ship».

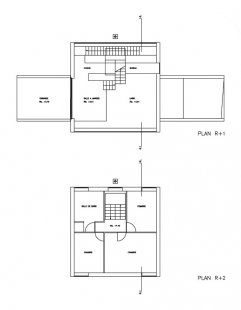

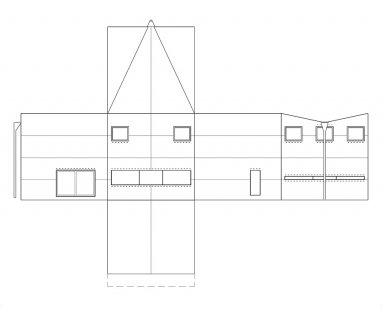

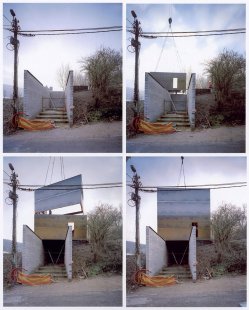

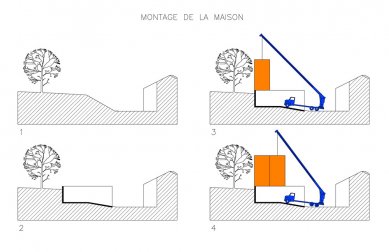

The metaphor of travel and ship applies doubly to the family house of Dejardin-Hendricé. Firstly, it has already made its first journey, as it was divided into four parts and transported to the construction site, where the parts were then welded together. Additionally, in terms of materials and construction methods, it resembles shipbuilding, which is also produced in the builder’s family metalworking shop alongside steel sculptures and storage silos. The economically sensible use of family options combined with the pioneering spirit of the appointed architect – in connection with specialists and a 1:1 scale trial model measuring 3 x 3 x 3 meters – led to this self-contained as well as radical result. The house is, of course, more than just a successful experiment in steel construction. A very rich interior space has emerged in a small area, of which the heavily reduced exterior gives no hint. The mass of the cube with edges of 7.5 x 7.5 x 7.5 meters derives from the format of corten sheets, which correspond to optimization for road transport: four equally sized prefabricated parts were delivered to the construction site by trailer and assembled there within seven hours. This was followed by interior completion and window installation. This perhaps spectacular process has been a traditional method for a long time. However, what is unusual is the structural arrangement of the elements and the way they are connected. For this is not a standard steel construction made up of stable elements such as columns, beams, and braces of the load-bearing frame, which, as Evelyn C. Frisch describes classic steel construction, «serves as the basis for the construction of ceilings, walls, and the outer shell».

Building with Steel Sheets

Pierre Hebbelinck chose an innovative as well as unorthodox approach. While steel constructions are normally designed from the inside out, with the spacing of individual columns serving as the basis for a filigree load-bearing structure, the outer shell being non-load-bearing and at most taking on a stiffening function, for the house of Dejardin-Hendricé it is exactly the opposite: the main load is supported by the outer shell. In terms of other details, the architect was inspired by construction principles from the shipbuilding industry, which he further developed. Similar principles have been used in wooden constructions for several years in the form of nailed sheets: here too, there are load-bearing thin sheets, and ribs inside prevent them from breaking. Such buildings with similar statics based on cardboard principles share the property that their walls can be reduced to only a few millimeters or even millimeters. This corresponds to another paradigm shift, in that for wooden or steel constructions, connections between themselves are linear, that openings in the walls are understood as window holes and can no longer be set as structural openings. It seems difficult to realize the new structural relationships on the facades, as the external walls must be insulated, which again diminishes their thin paper-like expression. Hebbelinck goes against these ingrained proportions and the arrangement of openings: the panoramic window on the side of the house with a beautiful view, as well as the horizontal slit window on the back, stretches across the entire width and almost reaches the edges of the building. This required adjustments to the load-bearing system, similar to hybridization, as rod beams were welded at the points between the windows to carry the loads. The openings on the upper floor are also set as far forward as possible and aligned with the facade. This way, no casing is created from the outside, and doubts about the massiveness of the cube may arise. Its walls appear oddly fragile and thin. In this sense, one does not immediately think of the monolith of Jean Nouvel for Expo 02 in Murten or Richard Serra's sculptures, but rather imagines creamy white repainted cardboard boxes by American abstract painter Cy Twombly. The fragility of these objects arises not only from the materials used (cardboard, wood, fabric, plaster), but also has to do with the color, which lends the surface liveliness and a sense of incompleteness. A similarly strong effect also arises with the corten facade of the house of Dejardin-Hendricé. Tactilely, it is sandy and rough. Originally blue-grey steel plates were almost immediately covered with rust.

Dematerialization of the Interior

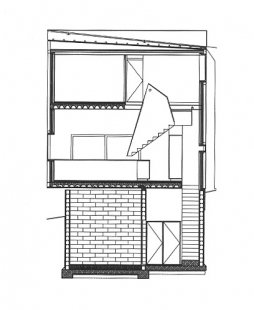

Inside, the steel did not remain in its original state, but was painted white. The double T-beams of the ceiling beams, with their characteristic view of white-painted trapezoidal sheets chosen instead of a ceiling in the living floor, together with the drywall-clad walls create a homogeneous effect and allow the relatively small space to shine generously. In contrast to this are the red-painted built-in and partially movable furniture. Red is also the floor of the living area, which is raised about one meter opposite the kitchen and dining room. Both these measures emphasize the complex spatial arrangement of the living floor, where Hebbelinck played a wonderful variety of different zones and light moods in just a few square meters.

In the interior, steel is also present with its sound. The last steps of the narrow staircase leading from the entrance to the living floor are made of steel, and moving along it clearly creates a transition between local building methods and prefabricated steel construction. Also, the staircase connecting the living area with the floor of sleeping chambers divided into modest rooms is made of steel. Walking on it resembles not only sound but also a slight vibration and the tactile nature of the handrail again inspires thoughts of ships: every inch of empty space under the living area is utilized as well as the air space above the upper staircase, where there is a platform on which a computer screen stands. The metaphor of ships and travel by Ernst Bloch is gladly accepted in the case of this house, not as a critical assessment: together with the builder open to experimentation, Hebbelinck succeeded in creating an extremely innovative contribution to the field of steel buildings, which is architecturally very convincing.

The house appears as a foreign body. Depending on whether the facades are dry or wet, it is rusty red or rusty brown. The two-story cube made of corten steel is situated in a quiet small village south of Liège. It is surrounded by traditional ochre cottages made from local limestone. It overlooks a meandering gently flowing river on the opposite side of the valley with forested hilltops. Nothing has been done to mitigate this sharp contrast. The house creates the impression that it has merely been placed here; for an indefinite period. It barely touches the ground, as if it needed to be quickly restored: an old retaining wall still holds the slope, and ivy-covered steps lead from the road to the upper meadow – the treatment of this dilapidated state vaguely resembles the then Upper Lawn Pavilion (a family house in Wiltshire from 1961) of the Smithsons. The only obvious surgical intervention in the terrain is two walls made of hollow concrete blocks running parallel. These walls slowly sink into the slope, upon which the cube of the house rests. The gap between the walls is chosen such that a protected entrance zone is created, which can also serve for parking a car.

The House as a Ship

Modern houses seem as if they are «prepared for travel», Ernst Bloch argued in his book «The Principle of Hope» (1959), and, like ships, they have a «taste for disappearance». Already in «The Heritage of This Time» (1935), there is a short excerpt on the topic of «houseboats» with the following sentences: «This house also no longer pretends to take root. [...] External stairs, riveted round windows only strengthen the impression that the house has become a ship».

The metaphor of travel and ship applies doubly to the family house of Dejardin-Hendricé. Firstly, it has already made its first journey, as it was divided into four parts and transported to the construction site, where the parts were then welded together. Additionally, in terms of materials and construction methods, it resembles shipbuilding, which is also produced in the builder’s family metalworking shop alongside steel sculptures and storage silos. The economically sensible use of family options combined with the pioneering spirit of the appointed architect – in connection with specialists and a 1:1 scale trial model measuring 3 x 3 x 3 meters – led to this self-contained as well as radical result. The house is, of course, more than just a successful experiment in steel construction. A very rich interior space has emerged in a small area, of which the heavily reduced exterior gives no hint. The mass of the cube with edges of 7.5 x 7.5 x 7.5 meters derives from the format of corten sheets, which correspond to optimization for road transport: four equally sized prefabricated parts were delivered to the construction site by trailer and assembled there within seven hours. This was followed by interior completion and window installation. This perhaps spectacular process has been a traditional method for a long time. However, what is unusual is the structural arrangement of the elements and the way they are connected. For this is not a standard steel construction made up of stable elements such as columns, beams, and braces of the load-bearing frame, which, as Evelyn C. Frisch describes classic steel construction, «serves as the basis for the construction of ceilings, walls, and the outer shell».

Building with Steel Sheets

Pierre Hebbelinck chose an innovative as well as unorthodox approach. While steel constructions are normally designed from the inside out, with the spacing of individual columns serving as the basis for a filigree load-bearing structure, the outer shell being non-load-bearing and at most taking on a stiffening function, for the house of Dejardin-Hendricé it is exactly the opposite: the main load is supported by the outer shell. In terms of other details, the architect was inspired by construction principles from the shipbuilding industry, which he further developed. Similar principles have been used in wooden constructions for several years in the form of nailed sheets: here too, there are load-bearing thin sheets, and ribs inside prevent them from breaking. Such buildings with similar statics based on cardboard principles share the property that their walls can be reduced to only a few millimeters or even millimeters. This corresponds to another paradigm shift, in that for wooden or steel constructions, connections between themselves are linear, that openings in the walls are understood as window holes and can no longer be set as structural openings. It seems difficult to realize the new structural relationships on the facades, as the external walls must be insulated, which again diminishes their thin paper-like expression. Hebbelinck goes against these ingrained proportions and the arrangement of openings: the panoramic window on the side of the house with a beautiful view, as well as the horizontal slit window on the back, stretches across the entire width and almost reaches the edges of the building. This required adjustments to the load-bearing system, similar to hybridization, as rod beams were welded at the points between the windows to carry the loads. The openings on the upper floor are also set as far forward as possible and aligned with the facade. This way, no casing is created from the outside, and doubts about the massiveness of the cube may arise. Its walls appear oddly fragile and thin. In this sense, one does not immediately think of the monolith of Jean Nouvel for Expo 02 in Murten or Richard Serra's sculptures, but rather imagines creamy white repainted cardboard boxes by American abstract painter Cy Twombly. The fragility of these objects arises not only from the materials used (cardboard, wood, fabric, plaster), but also has to do with the color, which lends the surface liveliness and a sense of incompleteness. A similarly strong effect also arises with the corten facade of the house of Dejardin-Hendricé. Tactilely, it is sandy and rough. Originally blue-grey steel plates were almost immediately covered with rust.

Dematerialization of the Interior

Inside, the steel did not remain in its original state, but was painted white. The double T-beams of the ceiling beams, with their characteristic view of white-painted trapezoidal sheets chosen instead of a ceiling in the living floor, together with the drywall-clad walls create a homogeneous effect and allow the relatively small space to shine generously. In contrast to this are the red-painted built-in and partially movable furniture. Red is also the floor of the living area, which is raised about one meter opposite the kitchen and dining room. Both these measures emphasize the complex spatial arrangement of the living floor, where Hebbelinck played a wonderful variety of different zones and light moods in just a few square meters.

In the interior, steel is also present with its sound. The last steps of the narrow staircase leading from the entrance to the living floor are made of steel, and moving along it clearly creates a transition between local building methods and prefabricated steel construction. Also, the staircase connecting the living area with the floor of sleeping chambers divided into modest rooms is made of steel. Walking on it resembles not only sound but also a slight vibration and the tactile nature of the handrail again inspires thoughts of ships: every inch of empty space under the living area is utilized as well as the air space above the upper staircase, where there is a platform on which a computer screen stands. The metaphor of ships and travel by Ernst Bloch is gladly accepted in the case of this house, not as a critical assessment: together with the builder open to experimentation, Hebbelinck succeeded in creating an extremely innovative contribution to the field of steel buildings, which is architecturally very convincing.

Christoph Wieser for Werk, Bauen und Wohnen 03/2007

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment