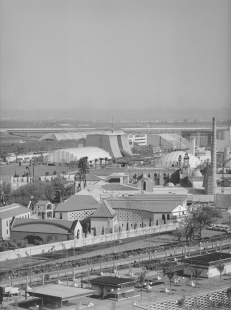

Japanese Pavilion at Expo '92

When I built this wooden structure, people somewhat surprisingly asked: "why did you build it out of wood?" It was a sincere reaction to my use of a different material than concrete, as I had worked with it for so many years.

Although the building material is an element that constructs space, I believe that the material itself cannot be the theme for an architect. Concrete is not my theme: I am more concerned with the spaces that concrete embraces. Similarly, when I do architecture out of wood, the main thing is not the wood, but the space that the wood defines and also the aesthetic qualities of the perceived wood.

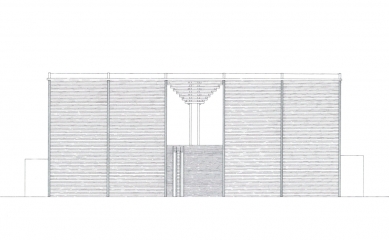

Starting from the idea that at international exhibitions, the architecture of the pavilion itself presents the national culture perhaps even more than the exhibits contained within, I tried to express Japanese culture through wooden architecture, the aesthetic sense of the Japanese, and their awareness. I felt that I wanted to show Europeans, whose culture is made of stone and walls, the cultural significance of wood and the beauty of wooden pillars.

One of the sources of Japanese culture I found in the Ise Shrine, which was first built in the 17th century. In this simple and austere architecture, set in a dense forest, surrounded by giant trees, the powerful creative will of the people is expressed in a primitive form. This temple has a austere and strong beauty, distinct from the delicate aesthetics that the Japanese have pursued over the last several centuries. In the Ise Shrine, there are two identical places located opposite each other, and the buildings are renewed every twenty years. If there is a desire for immortality expressed there, it lies in the unceasing yearning of the Japanese for purity, symbolized in the ritual of reconstruction (shinken sengu), during which completely new buildings are created - which is an immortality different from that achieved by the stone architecture of the West. It is said that twenty years is the time span in which one can effectively transfer knowledge of the special technologies required for the construction of the temple. At the same time, it is the time span during which untreated wood can be maintained. At Ise, one can see the majestic power, a certain restraint, and abstraction in the use of wood, completely different from the composition of elements in tea houses.

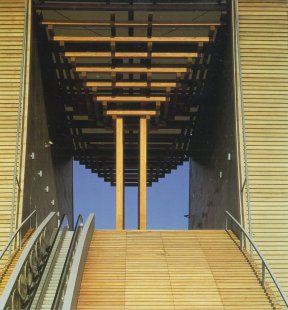

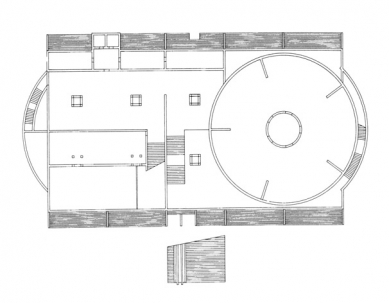

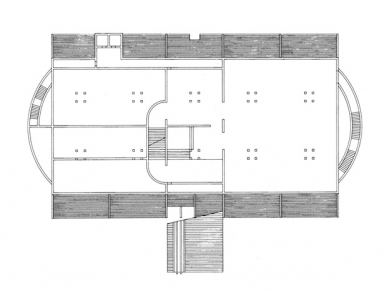

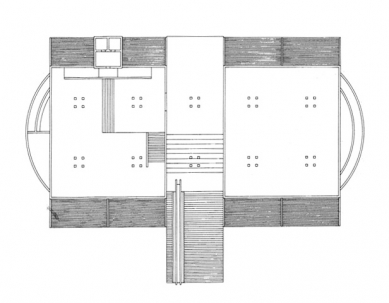

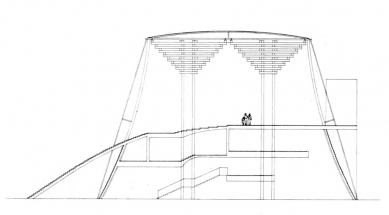

In the Japanese pavilion in Seville, I wanted to adopt this way of thinking and put it into the context of modern forms of expression. I wanted to strive for a free expression in the space defined by materials, limited essentially to wood both inside and outside, and to construct a rich space in which the strength of the columns would stand out. To achieve this intention, it was necessary to not neglect the texture and coloration of the materials. In the traditional conception, the living space of the Japanese was built from many natural materials, and their natural coloration was an object of admiration. I believe that natural colors - of wood, earth, and stone - can be reduced to monochrome. As I have been building predominantly in concrete for years, I have learned to find richness and recognize depth even in the seemingly dull world of monotony. The same applies when constructing wooden architecture. In the monochromatic world of Japanese dwellings and the power of abstraction of the temple in Ise, I seek my own roots.

The aesthetics of Japanese architecture is often described using the contrast between the architecture of the Nikko Toshogu temple from the 17th century and the Katsura palace. However, I believe that it is also possible to interpret Japanese architecture in terms of two poles - the period before and after the Sukiya style. While Sukiya architecture expresses its richness through the luster contained in details, the architecture of the earlier period (16th century), from which Sukiya style evolves, rather pursues refinement and grace of freedom within essentially one compositional method or one form - i.e., within limited boundaries. The powerful spirit of spatial volumes or the controlled light and contrasts of light and darkness are strongly impactful, for example. On the other hand, it can be said that the essence of the Sukiya style lies in the gentle control of nature and focuses its expressive means more on surfaces. The architecture of the tea house can serve as an archetypal example. The tea house is a close space in which the thoughts of the builder are evident everywhere, and his life is reflected in all the details. This aspect of Sukiya architecture has a powerful influence on contemporary Japanese architecture and is very significant. If we look at it differently, it could be said that even though the forms are completely different, the character of Sukiya is present in the flood of various postmodern styles that emerged in the 1980s, especially in the branch of Japanese postmodernism. Perhaps it is even more significant to realize what has grown from the tendencies of this period into a formal game, where, however, the original spirit of Sukiya has vanished.

In the consciousness of contemporary Japanese, wooden architecture is undoubtedly represented by the Sukiya style and the tea house. For me, in this context, wooden buildings are of interest, and at the same time, my focus is on the issue of the enduring struggle against the orientation towards surfaces and details, which are so characteristic of our internalized sensitivity to the Sukiya style. I want to return to the beginnings of wooden buildings and extract a more appropriate and powerful contemporary expression from them.

Although the building material is an element that constructs space, I believe that the material itself cannot be the theme for an architect. Concrete is not my theme: I am more concerned with the spaces that concrete embraces. Similarly, when I do architecture out of wood, the main thing is not the wood, but the space that the wood defines and also the aesthetic qualities of the perceived wood.

Starting from the idea that at international exhibitions, the architecture of the pavilion itself presents the national culture perhaps even more than the exhibits contained within, I tried to express Japanese culture through wooden architecture, the aesthetic sense of the Japanese, and their awareness. I felt that I wanted to show Europeans, whose culture is made of stone and walls, the cultural significance of wood and the beauty of wooden pillars.

One of the sources of Japanese culture I found in the Ise Shrine, which was first built in the 17th century. In this simple and austere architecture, set in a dense forest, surrounded by giant trees, the powerful creative will of the people is expressed in a primitive form. This temple has a austere and strong beauty, distinct from the delicate aesthetics that the Japanese have pursued over the last several centuries. In the Ise Shrine, there are two identical places located opposite each other, and the buildings are renewed every twenty years. If there is a desire for immortality expressed there, it lies in the unceasing yearning of the Japanese for purity, symbolized in the ritual of reconstruction (shinken sengu), during which completely new buildings are created - which is an immortality different from that achieved by the stone architecture of the West. It is said that twenty years is the time span in which one can effectively transfer knowledge of the special technologies required for the construction of the temple. At the same time, it is the time span during which untreated wood can be maintained. At Ise, one can see the majestic power, a certain restraint, and abstraction in the use of wood, completely different from the composition of elements in tea houses.

In the Japanese pavilion in Seville, I wanted to adopt this way of thinking and put it into the context of modern forms of expression. I wanted to strive for a free expression in the space defined by materials, limited essentially to wood both inside and outside, and to construct a rich space in which the strength of the columns would stand out. To achieve this intention, it was necessary to not neglect the texture and coloration of the materials. In the traditional conception, the living space of the Japanese was built from many natural materials, and their natural coloration was an object of admiration. I believe that natural colors - of wood, earth, and stone - can be reduced to monochrome. As I have been building predominantly in concrete for years, I have learned to find richness and recognize depth even in the seemingly dull world of monotony. The same applies when constructing wooden architecture. In the monochromatic world of Japanese dwellings and the power of abstraction of the temple in Ise, I seek my own roots.

The aesthetics of Japanese architecture is often described using the contrast between the architecture of the Nikko Toshogu temple from the 17th century and the Katsura palace. However, I believe that it is also possible to interpret Japanese architecture in terms of two poles - the period before and after the Sukiya style. While Sukiya architecture expresses its richness through the luster contained in details, the architecture of the earlier period (16th century), from which Sukiya style evolves, rather pursues refinement and grace of freedom within essentially one compositional method or one form - i.e., within limited boundaries. The powerful spirit of spatial volumes or the controlled light and contrasts of light and darkness are strongly impactful, for example. On the other hand, it can be said that the essence of the Sukiya style lies in the gentle control of nature and focuses its expressive means more on surfaces. The architecture of the tea house can serve as an archetypal example. The tea house is a close space in which the thoughts of the builder are evident everywhere, and his life is reflected in all the details. This aspect of Sukiya architecture has a powerful influence on contemporary Japanese architecture and is very significant. If we look at it differently, it could be said that even though the forms are completely different, the character of Sukiya is present in the flood of various postmodern styles that emerged in the 1980s, especially in the branch of Japanese postmodernism. Perhaps it is even more significant to realize what has grown from the tendencies of this period into a formal game, where, however, the original spirit of Sukiya has vanished.

In the consciousness of contemporary Japanese, wooden architecture is undoubtedly represented by the Sukiya style and the tea house. For me, in this context, wooden buildings are of interest, and at the same time, my focus is on the issue of the enduring struggle against the orientation towards surfaces and details, which are so characteristic of our internalized sensitivity to the Sukiya style. I want to return to the beginnings of wooden buildings and extract a more appropriate and powerful contemporary expression from them.

Translation of the accompanying report: Doc. PhDr. Lubomír Kostroň, M.A., CSc.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment