Capitol in Chandigarh

With the partition of India in July 1947, the city of Lahore, the capital of the Indian state of Punjab, found itself in the territory of Pakistan. The provisional capital became the mountain town of Shimla, however, it was clear that this was merely a temporary solution. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru prompted the search for a suitable location to build a new city from scratch, which would serve not only as the administrative center of Punjab but also as a home for many refugees from the territory that fell to Pakistan. The most ideal place was found at the foothills of the Himalayas, at a safe distance from the border with Pakistan, on the route between Delhi and Shimla. In 1966, Punjab was divided again, and since then Chandigarh has been the capital of two states: Punjab and Haryana.

For the planning of the new city, Nehru himself recommended the American architect Albert Mayer. The young architect of Polish origin Matthew Nowicki (who had, among other things, experience from the studio of Le Corbusier) was selected as the main architect of the project and the author of the future most important buildings. Their task was to create an open and clean city symbolizing the new democratic India, a "temple of the New India." A kind of prototype of a new Indian city that would offer residents different living conditions than the overcrowded existing Indian cities or the impoverished agricultural countryside.

The work was interrupted by tragedy. Nowicki died in a plane crash in Egypt in the summer of 1950. The search for a chief architect started anew. Suitable candidates appeared to be Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry from England, who felt they could not take on this task themselves and recommended contacting Le Corbusier. He hesitated at first about accepting the commission, refusing to accept the very low fee and additionally to go work in India. After being convinced that most of the work could be done in Paris and that he would have to spend only two months a year in India, and above all after being assured that he would influence the design of the entire city and be the principal author of the most important buildings, Le Corbusier finally accepted the commission. Thus, he became the head of the team, which included Jane Drew, Maxwell Fry, of course Le Corbusier's cousin Pierre Jeanneret, and several young Indian architects. Albert Mayer was to continue collaborating in the planning of the city, and Le Corbusier committed to building on his previous work. Le Corbusier had been waiting for a similar commission for 40 years, and it is no wonder that he soon pushed Mayer aside.

Le Corbusier visited India in the summer of 1951 and spent four working weeks there with his team. The main concept of the new city, which indeed stemmed from Mayer's original proposal, was completed in just four days. The main change was the straightening of all curved streets. The individual sectors, forming separate urban units, were planned as rectangles measuring approximately 1,200 x 800 m. They were separated by strips of greenery and wide streets. Transportation was based on the concept of "the seven Vs" - seven types of roads and sidewalks categorized by the type and speed of transport. Le Corbusier again proved to be a visionary, emphasizing primarily motor vehicle traffic in his design. As Kenneth Frampton notes, this resulted in a city "designed for cars in a country where many people do not even own a bicycle."

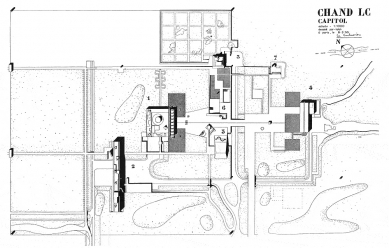

The Capitol itself forms the symbolic head of the city on its northeastern edge. It was to consist of four significant government buildings: the Governor's Palace, the Parliament, the Secretariat (Ministry office), and the Supreme Court building.

The most important challenge that Le Corbusier had to confront when designing the buildings of the Capitol was protecting the buildings from the scorching sun on one side and the heavy monsoon rains on the other. Le Corbusier drew inspiration from other Indian palaces, especially from the audience halls in the forts of Delhi and Agra, and the palace complex in Fatehpur Sikri made a great impression on him. The designs of his buildings for Chandigarh thus unify the motif of roofing, creating a symbolic umbrella under which the buildings lie, and the use of prominent sunshades on the façades, designed according to the principles of his modulor. At the same time, however, each of the buildings has its own expression based on its purpose.

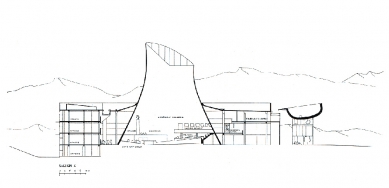

The Governor's Palace, designed in three variants between 1951-54, was to be the figurative "crown jewel" of the entire complex. Its characteristic silhouette with prominent corners referring to the sacred cows for Hindus (a motif that also appears in other buildings in the Capitol) was meant to end the axis formed by the system of ramps, gardens, and water surfaces impressively. The striking silhouette resembles the Diwan-I-Khas structure in Fatehpur Sikri. The background of the entire scene was to be the nearby Himalayas. The palace was ultimately not realized, as Jawaharlal Nehru did not consider it a democratic building.

For the planning of the new city, Nehru himself recommended the American architect Albert Mayer. The young architect of Polish origin Matthew Nowicki (who had, among other things, experience from the studio of Le Corbusier) was selected as the main architect of the project and the author of the future most important buildings. Their task was to create an open and clean city symbolizing the new democratic India, a "temple of the New India." A kind of prototype of a new Indian city that would offer residents different living conditions than the overcrowded existing Indian cities or the impoverished agricultural countryside.

The work was interrupted by tragedy. Nowicki died in a plane crash in Egypt in the summer of 1950. The search for a chief architect started anew. Suitable candidates appeared to be Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry from England, who felt they could not take on this task themselves and recommended contacting Le Corbusier. He hesitated at first about accepting the commission, refusing to accept the very low fee and additionally to go work in India. After being convinced that most of the work could be done in Paris and that he would have to spend only two months a year in India, and above all after being assured that he would influence the design of the entire city and be the principal author of the most important buildings, Le Corbusier finally accepted the commission. Thus, he became the head of the team, which included Jane Drew, Maxwell Fry, of course Le Corbusier's cousin Pierre Jeanneret, and several young Indian architects. Albert Mayer was to continue collaborating in the planning of the city, and Le Corbusier committed to building on his previous work. Le Corbusier had been waiting for a similar commission for 40 years, and it is no wonder that he soon pushed Mayer aside.

Le Corbusier visited India in the summer of 1951 and spent four working weeks there with his team. The main concept of the new city, which indeed stemmed from Mayer's original proposal, was completed in just four days. The main change was the straightening of all curved streets. The individual sectors, forming separate urban units, were planned as rectangles measuring approximately 1,200 x 800 m. They were separated by strips of greenery and wide streets. Transportation was based on the concept of "the seven Vs" - seven types of roads and sidewalks categorized by the type and speed of transport. Le Corbusier again proved to be a visionary, emphasizing primarily motor vehicle traffic in his design. As Kenneth Frampton notes, this resulted in a city "designed for cars in a country where many people do not even own a bicycle."

The Capitol itself forms the symbolic head of the city on its northeastern edge. It was to consist of four significant government buildings: the Governor's Palace, the Parliament, the Secretariat (Ministry office), and the Supreme Court building.

The most important challenge that Le Corbusier had to confront when designing the buildings of the Capitol was protecting the buildings from the scorching sun on one side and the heavy monsoon rains on the other. Le Corbusier drew inspiration from other Indian palaces, especially from the audience halls in the forts of Delhi and Agra, and the palace complex in Fatehpur Sikri made a great impression on him. The designs of his buildings for Chandigarh thus unify the motif of roofing, creating a symbolic umbrella under which the buildings lie, and the use of prominent sunshades on the façades, designed according to the principles of his modulor. At the same time, however, each of the buildings has its own expression based on its purpose.

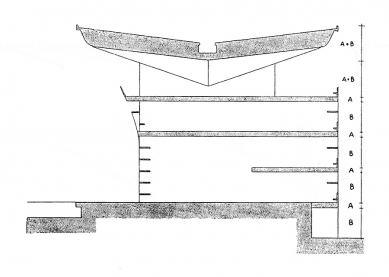

|

| Above: audience hall in the Red Fort in Delhi; below: audience hall in the fort in Agra. |

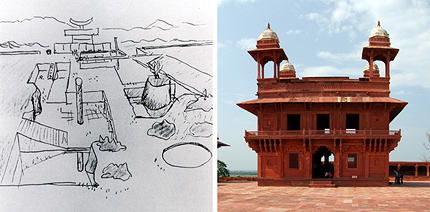

The Governor's Palace, designed in three variants between 1951-54, was to be the figurative "crown jewel" of the entire complex. Its characteristic silhouette with prominent corners referring to the sacred cows for Hindus (a motif that also appears in other buildings in the Capitol) was meant to end the axis formed by the system of ramps, gardens, and water surfaces impressively. The striking silhouette resembles the Diwan-I-Khas structure in Fatehpur Sikri. The background of the entire scene was to be the nearby Himalayas. The palace was ultimately not realized, as Jawaharlal Nehru did not consider it a democratic building.

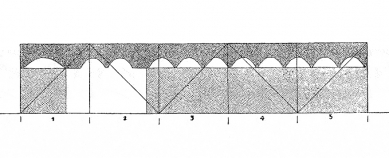

|

| Left: Design of the Governor's Palace from 1952; right: Diwan-I-Khas, Fatehpur Sikri. |

The first completed building was the judicial palace (1951–55). It consists of a robust open block with a roof reminiscent of a gigantic 1.4 m thick canopy resting on concrete pillars. According to Le Corbusier, this roof was meant to express "protection, majesty, and the might of law." A trio of colored pillars (red, yellow, and green) clearly marks the asymmetrically placed entrance, from which the Supreme Court is located on the left and the building containing eight courtrooms of lower instances is on the right. Offices on the upper floors are accessible via a series of ramps providing views of the nearby parliament building.

The Secretariat building (government office; 1951–58) was originally designed as a skyscraper, resembling an unrealized project for Algiers. However, the building would appear too dominant compared to the other two significant structures. Le Corbusier therefore laid the whole bulk down, resulting in a 254 m long and 42 m high prism, containing six interlinked blocks. Its façade consists of sunshades designed according to the proportions of the modulor.

Five out of the six blocks contain offices of administrative authorities, accessible via a central corridor, several internal vertical communication cores, and two ramps extending outdoors. The sixth block is designated for the offices of ministers, which have double the height compared to bureaucratic offices. This fact is reflected in the building's façade.

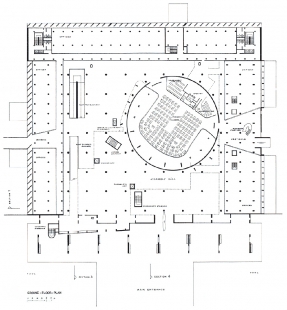

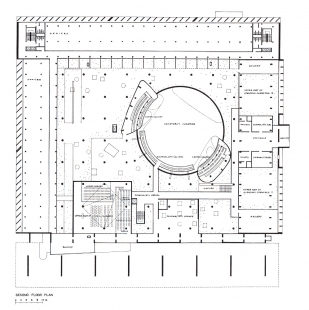

The last completed building is the Parliament building (1951–62). In designing it, Le Corbusier worked with light and shadow similarly to his chapel in Ronchamp or the monastery of La Tourette, which the Parliament building vaguely resembles.

The main entrance to the building features a distinctive portico, oriented towards the approximately 350 m distant Judicial Palace. When viewed from the main space, the Parliament is mirrored in the water surface. Towards the Secretariat, the surrounding terrain is lowered by two floors and connected to the main space by a ramp.

The actual legislative chamber is located in a tower, resembling the cooling towers that Le Corbusier saw in Ahmedabad. Sunrays were meant to shine into the chamber similarly to the space of the Hagia Sophia temple. At specific moments, they were to touch specific spots, reminding people that they are "children of the sun." Le Corbusier was fascinated by the buildings in the Jantar Mantar observatory (there are several of these 18th-century observatories, Le Corbusier visited Jantar Mantar in Delhi), which, in his words, "anchor man in the cosmos." On the sloping roof of the legislative tower, he proposed play with light and shadows. The motif of the sun's journey also appears, for instance, in the painting on the massive doors of the entrance portico.

A direct connotation with the astronomical instruments from Jantar Mantar is the Tower of Shadows, standing in the space between the Parliament and the Court. It consists of a collection of sunshades of varying sizes shading at different angles.

The symbol of the entire Capitol became the sculpture Open Hand standing above the Valley of Reflection. It symbolizes global harmony and expresses an appeal for mutual cooperation among people and nations around the world.

During the construction of the Capitol in the late 50s and early 60s, Le Corbusier focused on designing two smaller buildings for Chandigarh: a Museum and a Yacht Club.

The source of information was primarily the book by William J R Curtis: Le Corbusier: A penetrating and comprehensive study of the influential 20th-century architect, Phaidon, 2007.

A visit to Chandigarh leaves one with ambivalent feelings. The city itself is significantly greener and cleaner compared to other Indian metropolises. The residents like it, and it is recommended in tourist guides as an oasis for Western tourists who want to take a break from Indian reality at least for a moment.

However, the reality is less optimistic from the visitor's perspective. The artificially planned city, combined with the Indian sense of chaos, does not make for a good mix. It is pointless to elaborate on the fact that in this modern city, it is paradoxically very difficult to encounter an English-speaking person and that compared to other cities in India, it is very expensive here. Much sadder is the fact that the city is very difficult to navigate; moving along the four to six-lane roads with wide green belts on both sides forming the interface between the individual sectors, one quickly becomes lost. After a few hours, frustration sets in from the numbers everywhere that replace local names in organically grown cities.

The Capitol itself is today surrounded by a fence with barbed wire. Chandigarh has always faced a significant risk of terrorist attacks; however, this risk is perceived as even more real recently. Access to the area, and especially to the buildings themselves, is only possible with special permission, which is also issued in a completely different sector - i.e., several kilometers away (probably in sector 8). Today, entry to the Parliament and the Secretariat is via rear strictly guarded entrances; the space between the Parliament and the Judicial Palace is empty and slowly overgrown with grass. Only the Judicial Palace appears to function at first glance, unfortunately, it too is accessed via a back entrance.

During my short visit, I could not figure out how and where to obtain the necessary entry permission (when I oriented myself in the Kafkaesque system, I no longer had enough time to obtain it). Ultimately, the best strategy proved to be one of audacity and naivety, and I simply walked into the complex past the non-English speaking and confused military guard, and upon leaving the complex, had to climb over the fence. The strategy turned out to be successful (the military guard, to whom I had to account for my behavior, also did not speak English and the attempt to interrogate me ended in smiles on both sides); however, the Archiweb will have to wait for interior photographs of the buildings until my next visit...

The Secretariat building (government office; 1951–58) was originally designed as a skyscraper, resembling an unrealized project for Algiers. However, the building would appear too dominant compared to the other two significant structures. Le Corbusier therefore laid the whole bulk down, resulting in a 254 m long and 42 m high prism, containing six interlinked blocks. Its façade consists of sunshades designed according to the proportions of the modulor.

Five out of the six blocks contain offices of administrative authorities, accessible via a central corridor, several internal vertical communication cores, and two ramps extending outdoors. The sixth block is designated for the offices of ministers, which have double the height compared to bureaucratic offices. This fact is reflected in the building's façade.

The last completed building is the Parliament building (1951–62). In designing it, Le Corbusier worked with light and shadow similarly to his chapel in Ronchamp or the monastery of La Tourette, which the Parliament building vaguely resembles.

The main entrance to the building features a distinctive portico, oriented towards the approximately 350 m distant Judicial Palace. When viewed from the main space, the Parliament is mirrored in the water surface. Towards the Secretariat, the surrounding terrain is lowered by two floors and connected to the main space by a ramp.

The actual legislative chamber is located in a tower, resembling the cooling towers that Le Corbusier saw in Ahmedabad. Sunrays were meant to shine into the chamber similarly to the space of the Hagia Sophia temple. At specific moments, they were to touch specific spots, reminding people that they are "children of the sun." Le Corbusier was fascinated by the buildings in the Jantar Mantar observatory (there are several of these 18th-century observatories, Le Corbusier visited Jantar Mantar in Delhi), which, in his words, "anchor man in the cosmos." On the sloping roof of the legislative tower, he proposed play with light and shadows. The motif of the sun's journey also appears, for instance, in the painting on the massive doors of the entrance portico.

|

| Left: Jantar Mantar observatory (Jaipur); right: the top of the Parliament tower. |

A direct connotation with the astronomical instruments from Jantar Mantar is the Tower of Shadows, standing in the space between the Parliament and the Court. It consists of a collection of sunshades of varying sizes shading at different angles.

The symbol of the entire Capitol became the sculpture Open Hand standing above the Valley of Reflection. It symbolizes global harmony and expresses an appeal for mutual cooperation among people and nations around the world.

During the construction of the Capitol in the late 50s and early 60s, Le Corbusier focused on designing two smaller buildings for Chandigarh: a Museum and a Yacht Club.

The source of information was primarily the book by William J R Curtis: Le Corbusier: A penetrating and comprehensive study of the influential 20th-century architect, Phaidon, 2007.

A visit to Chandigarh leaves one with ambivalent feelings. The city itself is significantly greener and cleaner compared to other Indian metropolises. The residents like it, and it is recommended in tourist guides as an oasis for Western tourists who want to take a break from Indian reality at least for a moment.

However, the reality is less optimistic from the visitor's perspective. The artificially planned city, combined with the Indian sense of chaos, does not make for a good mix. It is pointless to elaborate on the fact that in this modern city, it is paradoxically very difficult to encounter an English-speaking person and that compared to other cities in India, it is very expensive here. Much sadder is the fact that the city is very difficult to navigate; moving along the four to six-lane roads with wide green belts on both sides forming the interface between the individual sectors, one quickly becomes lost. After a few hours, frustration sets in from the numbers everywhere that replace local names in organically grown cities.

The Capitol itself is today surrounded by a fence with barbed wire. Chandigarh has always faced a significant risk of terrorist attacks; however, this risk is perceived as even more real recently. Access to the area, and especially to the buildings themselves, is only possible with special permission, which is also issued in a completely different sector - i.e., several kilometers away (probably in sector 8). Today, entry to the Parliament and the Secretariat is via rear strictly guarded entrances; the space between the Parliament and the Judicial Palace is empty and slowly overgrown with grass. Only the Judicial Palace appears to function at first glance, unfortunately, it too is accessed via a back entrance.

During my short visit, I could not figure out how and where to obtain the necessary entry permission (when I oriented myself in the Kafkaesque system, I no longer had enough time to obtain it). Ultimately, the best strategy proved to be one of audacity and naivety, and I simply walked into the complex past the non-English speaking and confused military guard, and upon leaving the complex, had to climb over the fence. The strategy turned out to be successful (the military guard, to whom I had to account for my behavior, also did not speak English and the attempt to interrogate me ended in smiles on both sides); however, the Archiweb will have to wait for interior photographs of the buildings until my next visit...

|

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

4 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

povolení a interiéry

Ondřej

17.09.09 08:49

povolenie a interiéry II.

Rolo

17.09.09 10:00

"kosmické zakotvení"

Vích

17.09.09 11:29

meritko

fisla

17.09.09 01:46

show all comments