Church of St. Leopold at Steinhof

Church of St. Leopold

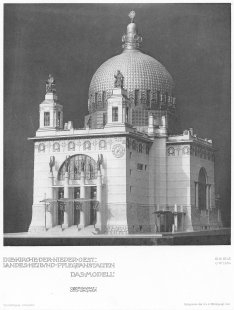

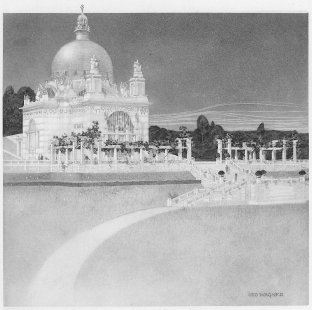

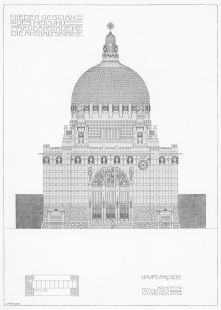

The Roman Catholic Church of St. Leopold, standing in the former institution for the insane in the fourteenth district of Vienna, Penzing, was constructed between 1904 and 1907 according to the design of the professor of the Vienna Academy, Otto Wagner, and is one of the most significant buildings of geometric secession. Wagner was commissioned to develop an urban design for the Lower Austrian State Hospital and Nursing Institute for Nervous and Mental Diseases on the hill of Steinhof, northwest of the city center, and he himself also built the church at the highest point, which clearly dominates the ensemble of around sixty simple hospital pavilions, designed by the Italian architect Carlo von Boog.

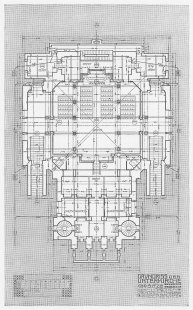

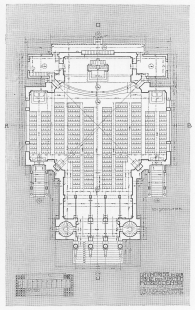

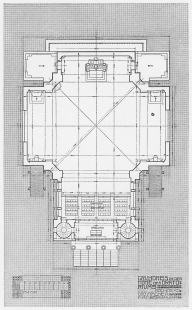

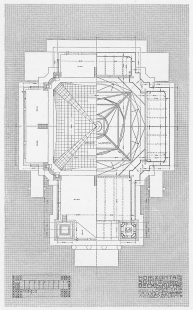

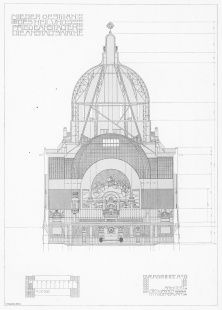

The building, made of white marble with large windows, is stripped of decoration as was possible at the time. Pure white lines are adorned only by gilded metal elements with crosses and laurel wreaths. In addition to the building itself, Wagner also designed the interior furnishings (altar, benches, lighting) and invited prominent artists of the time to realize other parts of the church: Koloman Moser, Wagner's student and co-founder of the Wiener Werkstätte, created the stained glass in the windows, sculptor Othmar Schimkowitz designed angel sculptures on the columns of the entrance portal and also on the altar, while sculptor Richard Luksch placed seated statues of patrons St. Leopold and preacher Severin on the side bell towers. The sculptors and painters were strongly influenced by the art of Byzantium and the Beuron artistic school. The copper dome with gilded details acts as a lighthouse and is visible from afar. The shape of the roof, resembling a halved lemon, led locals to nickname the hill Lemoniberg. In addition to modern aesthetics, Wagner also paid attention to practicality not only from a structural standpoint but also considered daily maintenance. Just as practicality was important to Wagner, so was the provision of sufficient light and fresh air within the interior. This rational approach to sacred architecture is crowned by a vessel for holy water, which is not in a basin where the faithful could dip their fingers, but holy water dripped from a container upon pressing a button to prevent the potential spread of infection. We are, after all, in a hospital complex, which was adapted not only with furniture without sharp corners to prevent injury, but the church also includes a medical room, toilets, and emergency exits for quick evacuation. The floor of the square nave is slightly sloped so that even the back rows have a good view of the main altar. In addition to a separate entrance for the nursing staff, entrances for male and female patients were also separated. Due to a lack of funds, it was ultimately not possible to realize the Stations of the Cross, install heating, or build a Protestant chapel and a Jewish synagogue in the basement.

The festive opening on October 8, 1907, was attended by the heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand d'Este. The archduke was not a great supporter of the new secession style. The contemporary newspapers belittled the significance of the building with the comment that “it is an irony of fate that the first significant secessionist building in Vienna was built for the insane” (Neue Freie Presse, October 6, 1907). In the ceremonial speech, Wagner's name was not mentioned at all, and subsequently, he did not receive any further commissions from the imperial family.

After a six-year reconstruction, the church was reopened in October 2006, and a new altar and pulpit from the Vienna studio Henke Schreieck were installed in the interior. A year later, three new bells were added.

Pavel Janák: Otto Wagner

Otto Wagner's appearance in contemporary architecture is a phenomenon that suddenly and extraordinarily emerges, and it is such a distinction that it takes on a constricted appearance of a personal affair. His demand for rationality and the logical, absolute dependence of architecture on the form of modern life has no analogs in the history of architecture, and his method of creation, reduced to rational processes, differs from the reality of creation in historical periods as well as from the tradition and practice of creation as it has been inherited through pseudo-historical periods to us. The positivity and emphasis with which Wagner articulates his statements enhances the deviation from common development to a conscious tendency, which is regarded as a break and abandonment.

Wagner's direction is — after fifty years and more, lost for the development of European architecture — a positive and firmly advancing continuation and, today, its results represent a stage of development without uncertainties and on the right path. It possesses all the signs of the art of its time: it has the character of spontaneous, natural expression; it is both essence and method in harmony with modern mental and physical life, defining artistically all its components; it is both a departure and a development that continues the historical evolution.

Twelve years ago, Wagner formulated in “Moderne Architektur” his conviction about future new architecture. The theses he articulated then have the grandeur of prophecy: they were expressed wholly, formulated decisively with boundless certainty of what was expected and with the enthusiasm that nearly makes it present; they differ from all those new, prejudiced reformers artificially constructed and so often crashing systems: there is nothing speculative, constructed in them that would require large, complex proofs — they state in short, simple evidence life facts and conclusions that are new but perfect and immutable. They are, in all these aspects, a direct spontaneous expression of life, far removed from all narrow personal thinking, something that, as a completed development, was prepared by itself and that must have been discovered or reached through the evolution of life. “This new style, modernity, will necessarily — if it wishes to embody us and our time — clearly express the striking change of the previous feelings, an almost complete abolition of romanticism and an almost all-consuming predominance of reason. This emerging style characterizing our time, built on the indicated basis, needs, like all previous styles, time for its development. But our fast-living century shows, even in this case, a tendency to achieve goals faster than has previously been the case; and thus we will soon reach it, greatly surprised by the results.” If these solemn, clear, and fully resonating words today reach their fulfillment and support by established facts, it is evidence of how little they were invented and theoretical, but how prophetic they were in sensing the future and in manifestation of the preparing forces.

The historical principle of serving architecture to life, its mission, to narrate life through physical form, Wagner raises in all its validity, but formulates it in accordance with the tendency of contemporary times with a strict wording — he formulates it in the Law of Purposefulness. He sincerely and manfully acknowledges the entire difference in the development of life. The instinctual, sensory lives of historical periods before us had the need for more sensory art and created more instinctively, which was reflected in the relationship of architectural concepts, which is a readiness and maturity of mental capabilities of life, to form and color; which in their performance are proportionate to sensuous inclinations; the two extreme possibilities of this relationship are barbarism and great classical style. With development, there is also a shift in mental life towards increasingly conscious actions and desires and a departure from expressing in more sensory means to expressions of concepts themselves. The modern era is characterized — against all previous ones — by a shift of the center of mental life to rational capacities, not only through their own strengthening but also through their dominance over all other mental activities: all components of mental life, once developed independently, faith, desire, and passion, and all willing are increasingly controlled and reduced by rational determination and decision-making; national and humanitarian ideals and previously instinctively felt and invoked notions are replaced by recognized and beneficial reasons. The tendency of Purpose becomes the highest deciding factor, and the fulfillment of purpose acquires almost values synonymous with perfection. The consciously, characterfully acting individual in the midst of a perfectly arranged whole is the ideal of the era — and this essence is taken as fundamental by the new architecture: not only because of its dependence on the life form but directly as one of its expressions, is a part of life and realizes — by sanctifying its spirit in its very energy the main character of the era. Perfectly structured architectures are for the contemporary period perfected compositions — thus, the era approaches creation with a changed aesthetic sentiment, which has absorbed much of the objectivity of understanding.

And likewise, the very method of creation has transitioned to logical, factual creation. Creation in historical periods was exclusively and only governed by feeling and the abilities of feeling; the quality of the outcome depended on its instinct, health, intensity, and purity. However, historical periods were fortunate in the accordance of creative feeling with the time, which lived entirely in life and for the life of the time. It can be stated that the creating instinct, through the development of history, departs from life itself increasingly, until in the periods of pseudo-historical styles it escapes directly through romantic nostalgia from life; the last remnants of this distancing are already entirely in the contemporary time — they are already diseases and treasons of feeling, as they lack all direction of divergence. These are symptoms of the degeneration of this free creative ability of feeling to its complete disappearance; in its place arises the creative activity of the logically, lawfully, and consciously creating modern man.

However, Otto Wagner's direction belongs to the context of the development of contemporary times; it is not a separate, personal construction, but firmly linked with the previous. Otto Wagner consciously stood against all revolutionary introductory slogans wanting to sever all connections with the old and raising fantastic plans and proposals for a return to empire and the style of iron, with his positive statement: “Every new style arose gradually from the previous one because new construction methods, new materials, new human tasks and views required a change or transformation of the existing forms.” His earlier activity — before his proclamation for a new architecture — was, like that of most of the time, inspired by the historical architecture of the renaissance and baroque. Within the constraints of this adopted style, his new progressive activity remained at the moment when he gained the conviction about the necessary new future of architecture because he perceived this departure as a further move from the outdated in connection with what is necessary and only natural, and what precisely the last experiences of contemporary times always invoke new interruptions and initiations serves as such evidence because in his own activity he subjected himself to the inertia of creative capabilities, which in him was stronger than ever. Thus, Wagner's development proceeds from a firm connection with the contemporary and embarks on the path of new striving like any progressive effort: with increased, more intense activity along the given tracks. The logic of the creation method, the strict pursuit of purpose is the new means, the quantitative plus, with which more precise results were to be achieved. Rational decisions that were the foundation of the new movement, because they established the impossibility of further stumbling through emotional romanticism of form, remain influential. They control the newly acquired and further utilized inventory of established forms — what is reused, column, pillar, cornice, emerges in its functions as confirmation of necessity against the earlier repetition of forms by mere tradition. All layout, subdivision, and individual members belong, in form, to an old artistic language, but have our present logical justification; all else from secondary creation, detail, and decoration could not withstand the judgment of contemporary standards — the relationships were absent and were too far removed from the spirit of the time to be formal means. Their function and approach, logically acknowledged, is filled by newly formed modern detail; the creative desire, previously limited by historical language of forms, takes this first opportunity for freely, non-binding new creation, which has been long overwhelmed by inactivity. However, it is also the last manifestation of immediate creation. Precisely the interchangeability of detail was in the new direction, which sought the most factual, a conviction, evidence against it: the episode of “exhibition style 1898,” so lush in its decorativeness, was a lesson for Wagner’s endeavor, which, gained from his own work, had a greater influential and guiding validity for the future. By overcoming this last, which — even if only by an analogy of its function — belonged to the outdated, the own development toward a positive, uniformly disciplined state begins. The new style is already defined in its entire spirit, and the path to its artistic means — penetrating to the very immutable core of things — is clear: these are geometric, prismatic, and cubical forms, the very essence of all forms, from which everything secondary had to fall away; it is their natural constructive assemblies as new compositional principles, with the function of decor - reduced only to accentuation, which as a framing and underlining lacks all independent form.

This is the stage of today's Wagnerian art. It provides its positive proof of his endeavor for the art of the era and enduring values. It is a natural, manly expression against all weaknesses and diseases of creation, as is the ideal of the age, against sentimentality, colorfulness, picturesque character, intimacy, and moodiness, all of which have nothing in common with the healthy, strong nature of the modern individual, nor with its resultant endeavor of not yielding and resisting personalities under all circumstances.

The modernity of Wagner's endeavor is finally complemented by his subordination of individual efforts to the whole, as is in accordance with the benefit of the general. In the work for the common good, it is not valuable distinction, individuality, but the intensity of the work brought; not originality, primacy, but the value of new work.

On the contrary: the desire for originality, individual distinction is directly harmful to the overall development, as it potentially introduces disruptive elements, i.e. creations whose reason is not the effort for the objective creation of value, but different values.

The greatness of Wagner's significance goes far beyond the importance of his own activity as a teacher and architect. Everything he has positively achieved through his progress and his art is a uniquely honorable work, but nothing more than merely a path of a discoverer: the discovery itself is infinitely greater than all the energy expended and produced by him and its results because the intrinsic value of the discovered — as with all world discoveries — lies outside the personality and outside all personal error or merit of the discoverer: the land he opened belongs to the common good and progress, and it is only to him that he had the courage — amidst all the stumbling and helplessness of creation — to turn to it without detours and distractions.

The building, made of white marble with large windows, is stripped of decoration as was possible at the time. Pure white lines are adorned only by gilded metal elements with crosses and laurel wreaths. In addition to the building itself, Wagner also designed the interior furnishings (altar, benches, lighting) and invited prominent artists of the time to realize other parts of the church: Koloman Moser, Wagner's student and co-founder of the Wiener Werkstätte, created the stained glass in the windows, sculptor Othmar Schimkowitz designed angel sculptures on the columns of the entrance portal and also on the altar, while sculptor Richard Luksch placed seated statues of patrons St. Leopold and preacher Severin on the side bell towers. The sculptors and painters were strongly influenced by the art of Byzantium and the Beuron artistic school. The copper dome with gilded details acts as a lighthouse and is visible from afar. The shape of the roof, resembling a halved lemon, led locals to nickname the hill Lemoniberg. In addition to modern aesthetics, Wagner also paid attention to practicality not only from a structural standpoint but also considered daily maintenance. Just as practicality was important to Wagner, so was the provision of sufficient light and fresh air within the interior. This rational approach to sacred architecture is crowned by a vessel for holy water, which is not in a basin where the faithful could dip their fingers, but holy water dripped from a container upon pressing a button to prevent the potential spread of infection. We are, after all, in a hospital complex, which was adapted not only with furniture without sharp corners to prevent injury, but the church also includes a medical room, toilets, and emergency exits for quick evacuation. The floor of the square nave is slightly sloped so that even the back rows have a good view of the main altar. In addition to a separate entrance for the nursing staff, entrances for male and female patients were also separated. Due to a lack of funds, it was ultimately not possible to realize the Stations of the Cross, install heating, or build a Protestant chapel and a Jewish synagogue in the basement.

The festive opening on October 8, 1907, was attended by the heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand d'Este. The archduke was not a great supporter of the new secession style. The contemporary newspapers belittled the significance of the building with the comment that “it is an irony of fate that the first significant secessionist building in Vienna was built for the insane” (Neue Freie Presse, October 6, 1907). In the ceremonial speech, Wagner's name was not mentioned at all, and subsequently, he did not receive any further commissions from the imperial family.

After a six-year reconstruction, the church was reopened in October 2006, and a new altar and pulpit from the Vienna studio Henke Schreieck were installed in the interior. A year later, three new bells were added.

PŠ

Pavel Janák: Otto Wagner

Otto Wagner's appearance in contemporary architecture is a phenomenon that suddenly and extraordinarily emerges, and it is such a distinction that it takes on a constricted appearance of a personal affair. His demand for rationality and the logical, absolute dependence of architecture on the form of modern life has no analogs in the history of architecture, and his method of creation, reduced to rational processes, differs from the reality of creation in historical periods as well as from the tradition and practice of creation as it has been inherited through pseudo-historical periods to us. The positivity and emphasis with which Wagner articulates his statements enhances the deviation from common development to a conscious tendency, which is regarded as a break and abandonment.

Wagner's direction is — after fifty years and more, lost for the development of European architecture — a positive and firmly advancing continuation and, today, its results represent a stage of development without uncertainties and on the right path. It possesses all the signs of the art of its time: it has the character of spontaneous, natural expression; it is both essence and method in harmony with modern mental and physical life, defining artistically all its components; it is both a departure and a development that continues the historical evolution.

Twelve years ago, Wagner formulated in “Moderne Architektur” his conviction about future new architecture. The theses he articulated then have the grandeur of prophecy: they were expressed wholly, formulated decisively with boundless certainty of what was expected and with the enthusiasm that nearly makes it present; they differ from all those new, prejudiced reformers artificially constructed and so often crashing systems: there is nothing speculative, constructed in them that would require large, complex proofs — they state in short, simple evidence life facts and conclusions that are new but perfect and immutable. They are, in all these aspects, a direct spontaneous expression of life, far removed from all narrow personal thinking, something that, as a completed development, was prepared by itself and that must have been discovered or reached through the evolution of life. “This new style, modernity, will necessarily — if it wishes to embody us and our time — clearly express the striking change of the previous feelings, an almost complete abolition of romanticism and an almost all-consuming predominance of reason. This emerging style characterizing our time, built on the indicated basis, needs, like all previous styles, time for its development. But our fast-living century shows, even in this case, a tendency to achieve goals faster than has previously been the case; and thus we will soon reach it, greatly surprised by the results.” If these solemn, clear, and fully resonating words today reach their fulfillment and support by established facts, it is evidence of how little they were invented and theoretical, but how prophetic they were in sensing the future and in manifestation of the preparing forces.

The historical principle of serving architecture to life, its mission, to narrate life through physical form, Wagner raises in all its validity, but formulates it in accordance with the tendency of contemporary times with a strict wording — he formulates it in the Law of Purposefulness. He sincerely and manfully acknowledges the entire difference in the development of life. The instinctual, sensory lives of historical periods before us had the need for more sensory art and created more instinctively, which was reflected in the relationship of architectural concepts, which is a readiness and maturity of mental capabilities of life, to form and color; which in their performance are proportionate to sensuous inclinations; the two extreme possibilities of this relationship are barbarism and great classical style. With development, there is also a shift in mental life towards increasingly conscious actions and desires and a departure from expressing in more sensory means to expressions of concepts themselves. The modern era is characterized — against all previous ones — by a shift of the center of mental life to rational capacities, not only through their own strengthening but also through their dominance over all other mental activities: all components of mental life, once developed independently, faith, desire, and passion, and all willing are increasingly controlled and reduced by rational determination and decision-making; national and humanitarian ideals and previously instinctively felt and invoked notions are replaced by recognized and beneficial reasons. The tendency of Purpose becomes the highest deciding factor, and the fulfillment of purpose acquires almost values synonymous with perfection. The consciously, characterfully acting individual in the midst of a perfectly arranged whole is the ideal of the era — and this essence is taken as fundamental by the new architecture: not only because of its dependence on the life form but directly as one of its expressions, is a part of life and realizes — by sanctifying its spirit in its very energy the main character of the era. Perfectly structured architectures are for the contemporary period perfected compositions — thus, the era approaches creation with a changed aesthetic sentiment, which has absorbed much of the objectivity of understanding.

And likewise, the very method of creation has transitioned to logical, factual creation. Creation in historical periods was exclusively and only governed by feeling and the abilities of feeling; the quality of the outcome depended on its instinct, health, intensity, and purity. However, historical periods were fortunate in the accordance of creative feeling with the time, which lived entirely in life and for the life of the time. It can be stated that the creating instinct, through the development of history, departs from life itself increasingly, until in the periods of pseudo-historical styles it escapes directly through romantic nostalgia from life; the last remnants of this distancing are already entirely in the contemporary time — they are already diseases and treasons of feeling, as they lack all direction of divergence. These are symptoms of the degeneration of this free creative ability of feeling to its complete disappearance; in its place arises the creative activity of the logically, lawfully, and consciously creating modern man.

However, Otto Wagner's direction belongs to the context of the development of contemporary times; it is not a separate, personal construction, but firmly linked with the previous. Otto Wagner consciously stood against all revolutionary introductory slogans wanting to sever all connections with the old and raising fantastic plans and proposals for a return to empire and the style of iron, with his positive statement: “Every new style arose gradually from the previous one because new construction methods, new materials, new human tasks and views required a change or transformation of the existing forms.” His earlier activity — before his proclamation for a new architecture — was, like that of most of the time, inspired by the historical architecture of the renaissance and baroque. Within the constraints of this adopted style, his new progressive activity remained at the moment when he gained the conviction about the necessary new future of architecture because he perceived this departure as a further move from the outdated in connection with what is necessary and only natural, and what precisely the last experiences of contemporary times always invoke new interruptions and initiations serves as such evidence because in his own activity he subjected himself to the inertia of creative capabilities, which in him was stronger than ever. Thus, Wagner's development proceeds from a firm connection with the contemporary and embarks on the path of new striving like any progressive effort: with increased, more intense activity along the given tracks. The logic of the creation method, the strict pursuit of purpose is the new means, the quantitative plus, with which more precise results were to be achieved. Rational decisions that were the foundation of the new movement, because they established the impossibility of further stumbling through emotional romanticism of form, remain influential. They control the newly acquired and further utilized inventory of established forms — what is reused, column, pillar, cornice, emerges in its functions as confirmation of necessity against the earlier repetition of forms by mere tradition. All layout, subdivision, and individual members belong, in form, to an old artistic language, but have our present logical justification; all else from secondary creation, detail, and decoration could not withstand the judgment of contemporary standards — the relationships were absent and were too far removed from the spirit of the time to be formal means. Their function and approach, logically acknowledged, is filled by newly formed modern detail; the creative desire, previously limited by historical language of forms, takes this first opportunity for freely, non-binding new creation, which has been long overwhelmed by inactivity. However, it is also the last manifestation of immediate creation. Precisely the interchangeability of detail was in the new direction, which sought the most factual, a conviction, evidence against it: the episode of “exhibition style 1898,” so lush in its decorativeness, was a lesson for Wagner’s endeavor, which, gained from his own work, had a greater influential and guiding validity for the future. By overcoming this last, which — even if only by an analogy of its function — belonged to the outdated, the own development toward a positive, uniformly disciplined state begins. The new style is already defined in its entire spirit, and the path to its artistic means — penetrating to the very immutable core of things — is clear: these are geometric, prismatic, and cubical forms, the very essence of all forms, from which everything secondary had to fall away; it is their natural constructive assemblies as new compositional principles, with the function of decor - reduced only to accentuation, which as a framing and underlining lacks all independent form.

This is the stage of today's Wagnerian art. It provides its positive proof of his endeavor for the art of the era and enduring values. It is a natural, manly expression against all weaknesses and diseases of creation, as is the ideal of the age, against sentimentality, colorfulness, picturesque character, intimacy, and moodiness, all of which have nothing in common with the healthy, strong nature of the modern individual, nor with its resultant endeavor of not yielding and resisting personalities under all circumstances.

The modernity of Wagner's endeavor is finally complemented by his subordination of individual efforts to the whole, as is in accordance with the benefit of the general. In the work for the common good, it is not valuable distinction, individuality, but the intensity of the work brought; not originality, primacy, but the value of new work.

On the contrary: the desire for originality, individual distinction is directly harmful to the overall development, as it potentially introduces disruptive elements, i.e. creations whose reason is not the effort for the objective creation of value, but different values.

The greatness of Wagner's significance goes far beyond the importance of his own activity as a teacher and architect. Everything he has positively achieved through his progress and his art is a uniquely honorable work, but nothing more than merely a path of a discoverer: the discovery itself is infinitely greater than all the energy expended and produced by him and its results because the intrinsic value of the discovered — as with all world discoveries — lies outside the personality and outside all personal error or merit of the discoverer: the land he opened belongs to the common good and progress, and it is only to him that he had the courage — amidst all the stumbling and helplessness of creation — to turn to it without detours and distractions.

Styl I (1908-09) s. 40-48

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment