Court Stop Hietzing

The Pavilion of the k. u. k. Most High Court in Hietzing

At the beginning of the last century, the Austro-Hungarian metropolis boldly invested in modern engineering constructions, and nothing suggested that the monarchy would collapse in the near future. The railway ministry established by the emperor aimed to build a rapid transport network and ensure the development of the entire country. Unsurprisingly, the greatest attention was focused on the capital city. Professor Otto Wagner from the Vienna Academy worked on the project of the urban steam railway from 1873, which he successfully implemented two decades later. For the Vienna railway, Wagner designed not only 35 stations (33 of which have survived in more or less altered form to this day) but also a number of bridges, tunnels, viaducts, and retaining walls. Wagner’s studio devoted great attention to these engineering works and addressed them down to the smallest details, including the design of heating units, lighting, and furniture arrangements. In the early 1890s, the Opava native Joseph Maria Olbrich worked in Wagner’s studio and was a co-founder of the artistic group Vienna Secession, whose handwriting is present in several drawings of the urban railway. By 1901, the railway had already measured over forty kilometers, and the entire engineering work was completely freed from the historicism of the 19th century, bearing a modern Secessionist spirit.

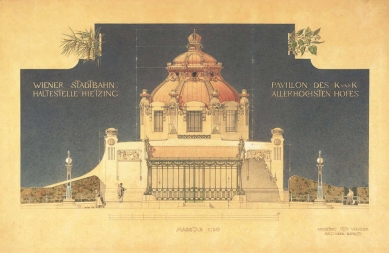

In 1898, a pair of Secessionist stops on the city railway was opened to the public at Karlsplatz in front of the Church of St. Charles Borromeo (J.B. Fischer von Erlach, 1737). A year later, Wagner completed another railway station located solely for one passenger—Emperor Franz Joseph I and his family—on the northeastern edge of the imperial palace Schönbrunn (J.B. Fischer von Erlach, 1701).

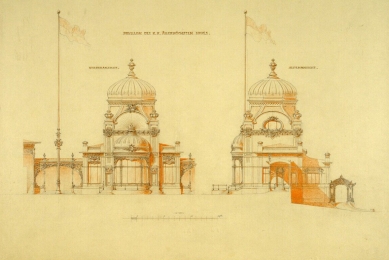

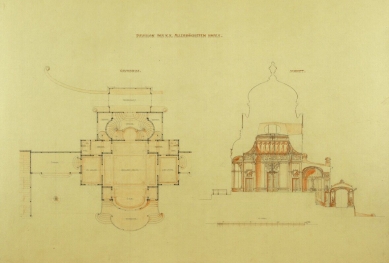

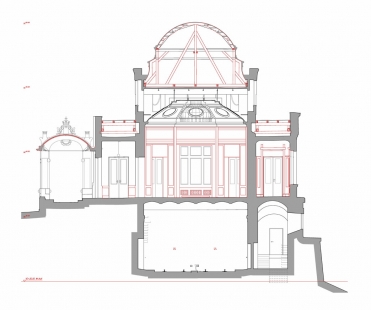

The ruler was to travel the half-kilometer journey from the baroque palace to the Secessionist stop in a carriage that was to go up a gentle paved ramp under a steel canopy bearing the emperor's initials, and then walk on foot into the octagonal waiting room, dominated by a painting by Carl Moll from 1898 depicting the Vienna panorama captured by the painter from a hot air balloon at an altitude of 3000 meters. The architects also devoted considerable attention to the design of the octagonal carpet on the floor, silk wall wallpapers, and golden floral motifs on the ceiling. The roof of the waiting room was crowned with a copper dome, which dialogued from a distance with the historical buildings of Schönbrunn Palace, without, however, copying any baroque form. Wagner even designed the appearance of the imperial carriages, which ultimately was not realized.

However, the court stop did not receive much admiration from the ruler, and the emperor only used it twice (at the ceremonial opening on June 16, 1899, and then on April 12, 1902). For Wagner, however, it was more important that the newly emerging style was blessed at the highest levels. Wagner was convinced that this small pavilion would have far greater significance for future generations than many other monumental buildings.

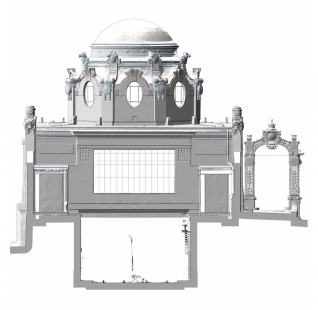

After the collapse of the monarchy, the pavilion lost its function, and both entrance staircases were demolished. In 1925, a new entrance to the platform was designed 160 meters to the west. Subsequently, the building served various purposes (including as a sculptor's studio) until it was decided in the 1980s to build a museum of the urban railway, and in 1989 the pavilion underwent its first not very sensitive renovation. In 2013-2014, another reconstruction took place for 1.8 million euros, handled by the Vienna expert Manfred Wehdorn.

In 1898, a pair of Secessionist stops on the city railway was opened to the public at Karlsplatz in front of the Church of St. Charles Borromeo (J.B. Fischer von Erlach, 1737). A year later, Wagner completed another railway station located solely for one passenger—Emperor Franz Joseph I and his family—on the northeastern edge of the imperial palace Schönbrunn (J.B. Fischer von Erlach, 1701).

The ruler was to travel the half-kilometer journey from the baroque palace to the Secessionist stop in a carriage that was to go up a gentle paved ramp under a steel canopy bearing the emperor's initials, and then walk on foot into the octagonal waiting room, dominated by a painting by Carl Moll from 1898 depicting the Vienna panorama captured by the painter from a hot air balloon at an altitude of 3000 meters. The architects also devoted considerable attention to the design of the octagonal carpet on the floor, silk wall wallpapers, and golden floral motifs on the ceiling. The roof of the waiting room was crowned with a copper dome, which dialogued from a distance with the historical buildings of Schönbrunn Palace, without, however, copying any baroque form. Wagner even designed the appearance of the imperial carriages, which ultimately was not realized.

However, the court stop did not receive much admiration from the ruler, and the emperor only used it twice (at the ceremonial opening on June 16, 1899, and then on April 12, 1902). For Wagner, however, it was more important that the newly emerging style was blessed at the highest levels. Wagner was convinced that this small pavilion would have far greater significance for future generations than many other monumental buildings.

After the collapse of the monarchy, the pavilion lost its function, and both entrance staircases were demolished. In 1925, a new entrance to the platform was designed 160 meters to the west. Subsequently, the building served various purposes (including as a sculptor's studio) until it was decided in the 1980s to build a museum of the urban railway, and in 1989 the pavilion underwent its first not very sensitive renovation. In 2013-2014, another reconstruction took place for 1.8 million euros, handled by the Vienna expert Manfred Wehdorn.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment