National House

Understanding the conditions in Moravia is difficult for those who observe them from afar. The delayed process of national liberation, the awakening of the self-confidence of a people who have yet to recognize their true strength and capabilities, acts on us in the kingdom as a reminiscence of the times of our fathers, or even grandfathers. The development of cities, suddenly liberated from the superficial veneer of German influence, is so characteristic of Moravia that it also impacts the artistic development in the land. Hardly anyone can name notable artistic figures in Moravia before this last phase, and it is rare to find any works at least on par with Czech standards that arose during that time. Therefore, we see the current scientific and artistic activity in an internal correlation with the expansion of national distinctiveness and economic viability. However, artistic conditions have not yet been settled; often, due to a lack of local talent, one resorts to foreign influences, which are often unhappy. Moravia has felt more than Bohemia the first, unrefined, and surrogate influences of pseudo-modern art and still suffers from them. Here, it seems that all the sins that caused the fever of urban regulations, sudden attacks of longing for fashionable architecture, and industrial products are multiplied. Factories producing heaps of elegance and tasteless junk have a larger market here, while the awakening of artistic taste in the people has heavier tasks. Larger cities testify to this, even when we omit Brno. Recently, Prostějov published a brochure describing the city’s development for the last 15 years. A milestone was the completion of the national house as a symbol of the city’s complete independence from German influence, and the years since the first external victory, starting from 1892, are seen as years of comprehensive development. However, if we look at the attached illustrations of public buildings and spaces, perspectives from a bird's eye view of interiors, we see a deep decline and stagnation in artistic terms: old squares ruined (especially Žerotín and Pernštýn) by the most banal new constructions, the old castle of the lords of Kravaře restored as a theatrical prospect at the end of the school square, and administrative buildings solved in the same template-like fashion as apartment houses, while new parts of the city appear helplessly scattered around without a unifying idea and goal.

And at the end of this development, which deserves to be called development only in the biological sense, emerges as a harbinger of a new era the building of the national house. Even if it were not connected to the entire modern artistic movement, it would already deserve credit for breaking into Prostějov with a new perspective on public buildings. This architecture initially seems a bit foreign to its surroundings, but it has an educational role in the broadest sense of the word. The younger generation will no longer walk around as if they do not understand the meaning of these forms and colors, and they will desire that the entire city revitalizes for their needs and according to their taste. Thus, standing at one end, the building starts a new period.

The intention to create a theater building in Prostějov naturally arose from the lack of suitable rooms. When, in the early 1890s, the city became Czech in its core and outwardly, occasional collections were organized for the construction of a theater, but it was only due to the rare bequest (170,000 K) from the first Czech mayor Vojáček and his wife that the idea received a more definite foundation, and it formally matured into realization through the establishment of a cooperative in the spring of 1905, which set itself a broader program: to build not only a theater and a community house, as was the original intention of the Vojáček couple, but also to establish a social center for the rapidly developing city. Until that time, Prostějov—despite being the largest Czech city in Moravia, with 28,000 inhabitants—had no suitable rooms and had been solely reliant on the recently built Worker’s House, which, despite its spaciousness, was particularly unsuitable for theater purposes.

Therefore, the establishment of the cooperative was welcomed with such sympathy that immediate collections raised 60,000 K, and the municipality donated a plot of land for the construction of the building in the very center of the city and sold materials to the cooperative at cost price. The cooperative undertook vigorous activity to obtain proper plans for the building, with construction set to begin, given favorable building conditions, no later than the beginning of 1908. The submission of proposals was entrusted directly to architect J. Kotěra without a bidding process. He completed the plans in collaboration with architect Richard Novák and builder O. Pokorný. Additionally, the sculptural work was done by Professor St. Sucharda, the panel in the vestibule was painted by J. Preisler, the decorative painting of the lounges and proscenium boxes was executed by Fr. Kysela, and the models for the figurative chandelier in the auditorium and the figurative decoration of the fireplace in the restaurant were created by K. Petr.

Construction began on June 1, 1906, and it was roughly completed and covered within that same year; it was finished in November 1907. The ceremonial opening took place on November 30 - December 1, 1907, and the municipality took ownership of the building. The overall cost amounted to 780,000 K, of which 100,000 K was allocated for interior equipment and theatrical decorations.

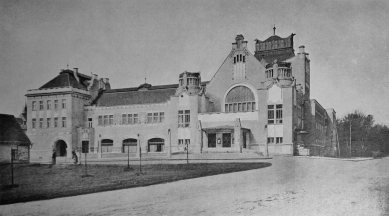

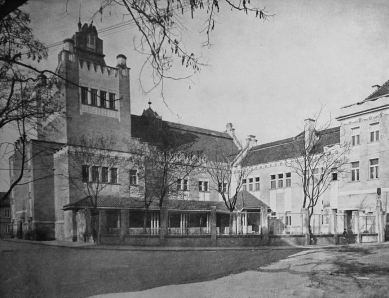

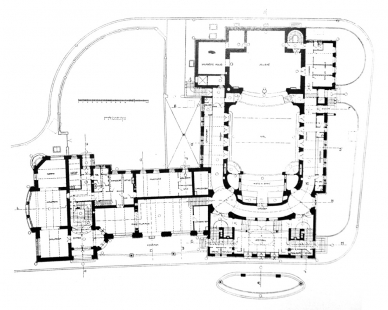

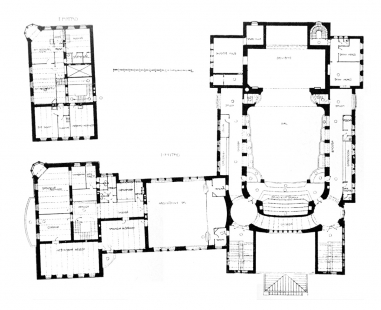

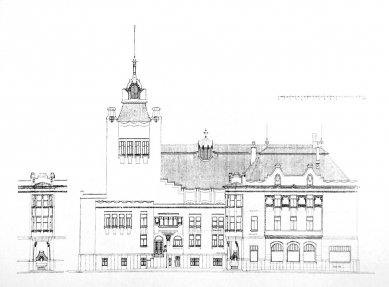

The building (The following description serves to supplement the illustrations, especially in terms of material and color) of the National House stands in a favorable location, capable of external representation even in its current state; it nearly touches the main square and the main street leading from the station and from Olomouc. Diverse in its functions, it is also diverse in mass. The façade of the theater block lies along Smetan’s Square, while the façade of the community house faces the wide park area, into which the main street expands before the building. The garden, enclosed by both blocks, transitions into a city park.

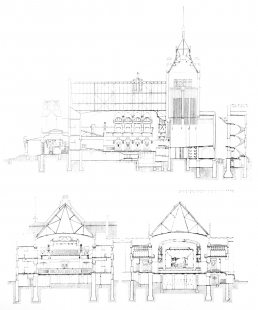

The theater block contains an auditorium for about 900 people, with the corresponding vestibule, staircase, lounge, corridors, and cloakrooms, a stage with actors’ dressing rooms, decoration storage, and other accessories; the community block, partially two-story, has a restaurant and café with appropriate adjoining rooms on the ground floor, a lecture hall and rooms for clubs on the first floor, and a club room and staff apartments on the second floor. The building is of brick, with construction in the theater block and in the ground floor and lecture hall of steel and reinforced concrete, elsewhere timber. The masonry is plastered, with a smoothed light gray finish, and the ornamental sgraffito decoration is reddish-brown with differently colored details. The base is concrete with sandstone framing. The roof is covered with red tiles. The underpass and the termination of the pylons, as well as the covering of the gables and attic, are made of sandstone. Ventilators, lightning rods, and the entire completion of the tower are made of green-painted sheet metal, with the garlands on the pylons being hammered from copper. The porch is made of white-painted and decorated wood and covered with tiles. The lanterns in front of the building are made of wrought iron, partly using copper.

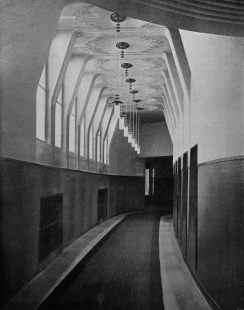

The interior of the theater block: The vestibule has white walls, a black base, and reddish-brown marble pilasters; the columns are serpentine; the stairs are made of light, polished granite, and the flooring consists of white, black, and reddish-brown ceramics. The windows and doors are of oak. The chandeliers are bronze, and the ceiling fixtures are brass. The staircase to the upper levels is similarly sustained in materials and color. The corridors are partly lined with violet linoleum on white walls, and dark red carpets lie on the terrazzo black-and-white flooring. The lounges for the audience have wooden ceilings of polished natural oak and walnut, door and fireplace cladding are of gray-red marble, and the windows and doors are of unpolished oak with brass parts. The auditorium is lined with yellow-green linoleum on the walls; the ceiling is light yellow with plastic decorations gilded and partially patinated and white grids; the doors are oak, glazed with faceted glass, windows with opalescent panels (green, blue, white) in lead; the furniture is of bent wood, with green upholstery, and the curtain and portieres are yellow-green with an irregular design and color-applied ornament; the chandeliers and armatures for the lamps are from bronze, chiselled, partially gilded and brown patinated.

The interior of the community block: The restaurant with two rooms has walls and a ceiling in white and yellow-gray, partially lined with green linoleum; the fireplace is of red marble; the plaster statue is patinated, with inserted decorations of fired glazed clay; the windows and doors are of natural oak; the chandeliers are brass; the furniture in the front room is blue-stained oak, while in the back, it is polished light walnut, with gray-yellow upholstery; the carpets are green. The café has in the first room a light gray ceiling and green patterned walls, partially lined with green matting, and in the reading room, there is gold Japanese wallpaper on the walls; the windows and doors are of oak, lighting fixtures are brass; the furniture is of polished natural oak and rosewood, with yellow-gray upholstery in the reading room; table tops are green marble. The lecture hall has a white and white-yellow ceiling and walls, wall cladding made of natural polished oak and black pear; the windows and doors are white lacquered; metal parts are brass. Other community rooms such as the discussion hall, lounge, and library are wallpapered; cabinetry work is mostly white lacquered, and the furniture is either walnut or rainbow with brass lighting fixtures.

And at the end of this development, which deserves to be called development only in the biological sense, emerges as a harbinger of a new era the building of the national house. Even if it were not connected to the entire modern artistic movement, it would already deserve credit for breaking into Prostějov with a new perspective on public buildings. This architecture initially seems a bit foreign to its surroundings, but it has an educational role in the broadest sense of the word. The younger generation will no longer walk around as if they do not understand the meaning of these forms and colors, and they will desire that the entire city revitalizes for their needs and according to their taste. Thus, standing at one end, the building starts a new period.

The intention to create a theater building in Prostějov naturally arose from the lack of suitable rooms. When, in the early 1890s, the city became Czech in its core and outwardly, occasional collections were organized for the construction of a theater, but it was only due to the rare bequest (170,000 K) from the first Czech mayor Vojáček and his wife that the idea received a more definite foundation, and it formally matured into realization through the establishment of a cooperative in the spring of 1905, which set itself a broader program: to build not only a theater and a community house, as was the original intention of the Vojáček couple, but also to establish a social center for the rapidly developing city. Until that time, Prostějov—despite being the largest Czech city in Moravia, with 28,000 inhabitants—had no suitable rooms and had been solely reliant on the recently built Worker’s House, which, despite its spaciousness, was particularly unsuitable for theater purposes.

Therefore, the establishment of the cooperative was welcomed with such sympathy that immediate collections raised 60,000 K, and the municipality donated a plot of land for the construction of the building in the very center of the city and sold materials to the cooperative at cost price. The cooperative undertook vigorous activity to obtain proper plans for the building, with construction set to begin, given favorable building conditions, no later than the beginning of 1908. The submission of proposals was entrusted directly to architect J. Kotěra without a bidding process. He completed the plans in collaboration with architect Richard Novák and builder O. Pokorný. Additionally, the sculptural work was done by Professor St. Sucharda, the panel in the vestibule was painted by J. Preisler, the decorative painting of the lounges and proscenium boxes was executed by Fr. Kysela, and the models for the figurative chandelier in the auditorium and the figurative decoration of the fireplace in the restaurant were created by K. Petr.

Construction began on June 1, 1906, and it was roughly completed and covered within that same year; it was finished in November 1907. The ceremonial opening took place on November 30 - December 1, 1907, and the municipality took ownership of the building. The overall cost amounted to 780,000 K, of which 100,000 K was allocated for interior equipment and theatrical decorations.

The building (The following description serves to supplement the illustrations, especially in terms of material and color) of the National House stands in a favorable location, capable of external representation even in its current state; it nearly touches the main square and the main street leading from the station and from Olomouc. Diverse in its functions, it is also diverse in mass. The façade of the theater block lies along Smetan’s Square, while the façade of the community house faces the wide park area, into which the main street expands before the building. The garden, enclosed by both blocks, transitions into a city park.

The theater block contains an auditorium for about 900 people, with the corresponding vestibule, staircase, lounge, corridors, and cloakrooms, a stage with actors’ dressing rooms, decoration storage, and other accessories; the community block, partially two-story, has a restaurant and café with appropriate adjoining rooms on the ground floor, a lecture hall and rooms for clubs on the first floor, and a club room and staff apartments on the second floor. The building is of brick, with construction in the theater block and in the ground floor and lecture hall of steel and reinforced concrete, elsewhere timber. The masonry is plastered, with a smoothed light gray finish, and the ornamental sgraffito decoration is reddish-brown with differently colored details. The base is concrete with sandstone framing. The roof is covered with red tiles. The underpass and the termination of the pylons, as well as the covering of the gables and attic, are made of sandstone. Ventilators, lightning rods, and the entire completion of the tower are made of green-painted sheet metal, with the garlands on the pylons being hammered from copper. The porch is made of white-painted and decorated wood and covered with tiles. The lanterns in front of the building are made of wrought iron, partly using copper.

The interior of the theater block: The vestibule has white walls, a black base, and reddish-brown marble pilasters; the columns are serpentine; the stairs are made of light, polished granite, and the flooring consists of white, black, and reddish-brown ceramics. The windows and doors are of oak. The chandeliers are bronze, and the ceiling fixtures are brass. The staircase to the upper levels is similarly sustained in materials and color. The corridors are partly lined with violet linoleum on white walls, and dark red carpets lie on the terrazzo black-and-white flooring. The lounges for the audience have wooden ceilings of polished natural oak and walnut, door and fireplace cladding are of gray-red marble, and the windows and doors are of unpolished oak with brass parts. The auditorium is lined with yellow-green linoleum on the walls; the ceiling is light yellow with plastic decorations gilded and partially patinated and white grids; the doors are oak, glazed with faceted glass, windows with opalescent panels (green, blue, white) in lead; the furniture is of bent wood, with green upholstery, and the curtain and portieres are yellow-green with an irregular design and color-applied ornament; the chandeliers and armatures for the lamps are from bronze, chiselled, partially gilded and brown patinated.

The interior of the community block: The restaurant with two rooms has walls and a ceiling in white and yellow-gray, partially lined with green linoleum; the fireplace is of red marble; the plaster statue is patinated, with inserted decorations of fired glazed clay; the windows and doors are of natural oak; the chandeliers are brass; the furniture in the front room is blue-stained oak, while in the back, it is polished light walnut, with gray-yellow upholstery; the carpets are green. The café has in the first room a light gray ceiling and green patterned walls, partially lined with green matting, and in the reading room, there is gold Japanese wallpaper on the walls; the windows and doors are of oak, lighting fixtures are brass; the furniture is of polished natural oak and rosewood, with yellow-gray upholstery in the reading room; table tops are green marble. The lecture hall has a white and white-yellow ceiling and walls, wall cladding made of natural polished oak and black pear; the windows and doors are white lacquered; metal parts are brass. Other community rooms such as the discussion hall, lounge, and library are wallpapered; cabinetry work is mostly white lacquered, and the furniture is either walnut or rainbow with brass lighting fixtures.

A.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment