Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau

When a problem really preoccupies us we carry it about with us. And then one day we suddenly hit on the solution, and often find its confirmation turning the next street corner. Thus the proportions of the huge scaffolding in front of the Bon Marché confirmed my theory of the scale that urban buildings ought to embody in the future. It seems clear that buildings should be set back further and further from the street, that the open spaces so created should be made larger and larger ; and that we should build upwards to two or three times the existing height-limit. Were this the case the present height of rooms in ordinary flats, which architectural practice has fixed at 9-12 feet, could be sensibly increased. Future groundplans will postulate fresh architectural conditions which will lead to the adoption of a new worm of height ; probable 18-22 feet.

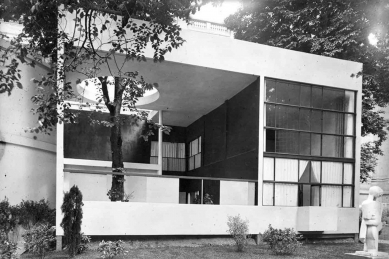

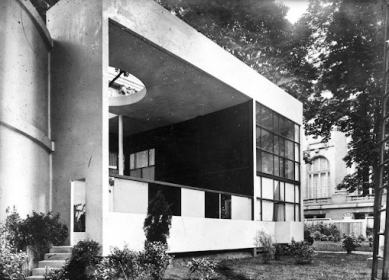

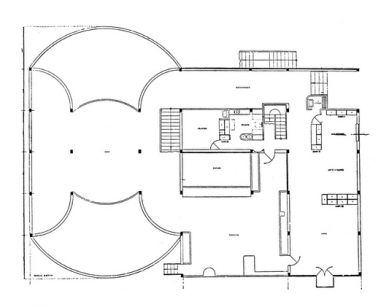

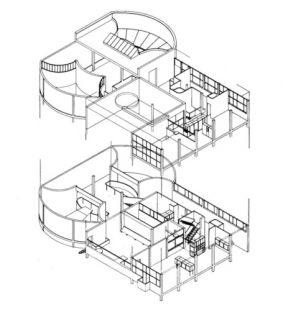

The "Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau" at the Paris Exposition des Arts Décoratifs of 1925 was a signal triumph over difficulties. No funds were available, no site was forthcoming, and the Organizing Committee of the Exhibition refused to allow the scheme I had drawn up to proceed. The program of that scheme was as follows, the rejection of decorative art as such, accompanied by an affirmation that the sphere of architecture embraces every detail of household furnishing, the street as well as the house, and a wider world still beyond both. My intention was to illustrate how, by virtue of the selective principle (standardization applied to mass-production), industry creates pure forms ; and to stress the intrinsic value of this pure form of art that is the result of it. Secondly to show the radical transformations and structural liberties reinforced concrete and steel allow us to envisage in urban housing - in other words that a dwelling tan be standardized to meet the needs of men whose lives are standardized. And thirdly to demonstrate that these comfortable and elegant units of habitation, these practical machines for living in, could be agglomerated in long, lofty blocks of villa-flats. The "Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau" was accordingly designed as a typical cell-unit in just such a block of multiple villa-flats. It consisted of a minimum dwelling with its own roof-terrace. Attached to this cell-unit was an annexe in the form of a rotunda containing detailed studies of town-planning schemes; two large dioramas, each a hundred square meters in area, one of which showed the 1922 "Plan for a Modern City of 3,000,000 Inhabitants"; and the other the "Voisin Plan" which proposed the creation of a new business centre in the heart of Paris. On the walls were methodically worked out plans for cruciform skyscrapers, housing colonies with staggered lay-outs, and a whole range of types new to architecture that were the fruit of a mind preoccupied with the problems of the future.

The Building Committee of the Exhibition made use of ifs powers to evince the most marked hostility to the execution of my scheme. It was only owing to the presence of M. de Monzie, then Minister of Fine Arts, who came to inaugurate the Exhibition, that the Committee agreed to remove the 18 ft. pallisade it had had erected in front of the pavilion to screen it from the public gaze. Notwithstanding that the international Jury of the Exhibition wished to bestow ifs highest award on this design of mine, ifs French vice-president - though a man of outstanding merit, who had himself been an avant-garde architect - opposed the proposal on the ground that "there was no architecture" in my pavilion!

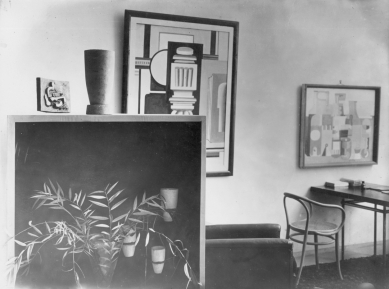

In 1929 we realize, looking back, that the "Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau" was a turning point in the design of modern interiors and a milestone in the evolution of architecture. A new term has replaced the old word furniture, which stood for fossilizing traditions and limited utilization. That new term is equipment, which implies the logical classification of the various elements necessary to run a house that results from their practical analysis. Standardized fitted cupboards, built into the walls or suspended from them, are allocated to every point in the home where a daily function has to be performed - wardrobes for hanging suits and dresses; cupboards for underclothes, household linen, plate and glass; shelves for ornaments and shelves for books - have replaced all the innumerable varieties of superannuated furniture that where known by half-a-hundred different names. This new domestic equipment, which is no longer of wood but of metal, is made in the factories that used to manufacture office-furniture. To-day it represents the entire "furnishing" of a home, leaving a maximum of unencumbered space in every room, and only chairs and tables to fill it. The scientific study of chairs and tables has, in turn, led to entirely new conceptions of what their form should be : a form which is no longer decorative but purely functional. The evolution of modern manners has banished the old conventional ritual that used to dictate our sitting posture. Since we can sit in many different positions, the new shapes of chair which a tubular-steel or strip-metal framework make possible ought to provide for all of them. Wood, being a traditional material, limited the scope of the designer's initiative.

To equip a house properly requires long deliberation. As a result of lectures, articles and private discussions a practical classification of what is needed has now been arrived at which heralds a new era in domestic organization.

The "Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau" at the Paris Exposition des Arts Décoratifs of 1925 was a signal triumph over difficulties. No funds were available, no site was forthcoming, and the Organizing Committee of the Exhibition refused to allow the scheme I had drawn up to proceed. The program of that scheme was as follows, the rejection of decorative art as such, accompanied by an affirmation that the sphere of architecture embraces every detail of household furnishing, the street as well as the house, and a wider world still beyond both. My intention was to illustrate how, by virtue of the selective principle (standardization applied to mass-production), industry creates pure forms ; and to stress the intrinsic value of this pure form of art that is the result of it. Secondly to show the radical transformations and structural liberties reinforced concrete and steel allow us to envisage in urban housing - in other words that a dwelling tan be standardized to meet the needs of men whose lives are standardized. And thirdly to demonstrate that these comfortable and elegant units of habitation, these practical machines for living in, could be agglomerated in long, lofty blocks of villa-flats. The "Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau" was accordingly designed as a typical cell-unit in just such a block of multiple villa-flats. It consisted of a minimum dwelling with its own roof-terrace. Attached to this cell-unit was an annexe in the form of a rotunda containing detailed studies of town-planning schemes; two large dioramas, each a hundred square meters in area, one of which showed the 1922 "Plan for a Modern City of 3,000,000 Inhabitants"; and the other the "Voisin Plan" which proposed the creation of a new business centre in the heart of Paris. On the walls were methodically worked out plans for cruciform skyscrapers, housing colonies with staggered lay-outs, and a whole range of types new to architecture that were the fruit of a mind preoccupied with the problems of the future.

The Building Committee of the Exhibition made use of ifs powers to evince the most marked hostility to the execution of my scheme. It was only owing to the presence of M. de Monzie, then Minister of Fine Arts, who came to inaugurate the Exhibition, that the Committee agreed to remove the 18 ft. pallisade it had had erected in front of the pavilion to screen it from the public gaze. Notwithstanding that the international Jury of the Exhibition wished to bestow ifs highest award on this design of mine, ifs French vice-president - though a man of outstanding merit, who had himself been an avant-garde architect - opposed the proposal on the ground that "there was no architecture" in my pavilion!

In 1929 we realize, looking back, that the "Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau" was a turning point in the design of modern interiors and a milestone in the evolution of architecture. A new term has replaced the old word furniture, which stood for fossilizing traditions and limited utilization. That new term is equipment, which implies the logical classification of the various elements necessary to run a house that results from their practical analysis. Standardized fitted cupboards, built into the walls or suspended from them, are allocated to every point in the home where a daily function has to be performed - wardrobes for hanging suits and dresses; cupboards for underclothes, household linen, plate and glass; shelves for ornaments and shelves for books - have replaced all the innumerable varieties of superannuated furniture that where known by half-a-hundred different names. This new domestic equipment, which is no longer of wood but of metal, is made in the factories that used to manufacture office-furniture. To-day it represents the entire "furnishing" of a home, leaving a maximum of unencumbered space in every room, and only chairs and tables to fill it. The scientific study of chairs and tables has, in turn, led to entirely new conceptions of what their form should be : a form which is no longer decorative but purely functional. The evolution of modern manners has banished the old conventional ritual that used to dictate our sitting posture. Since we can sit in many different positions, the new shapes of chair which a tubular-steel or strip-metal framework make possible ought to provide for all of them. Wood, being a traditional material, limited the scope of the designer's initiative.

To equip a house properly requires long deliberation. As a result of lectures, articles and private discussions a practical classification of what is needed has now been arrived at which heralds a new era in domestic organization.

Extract from Le Corbusier, Oeuvre complète, volume 1, 1910-1929

0 comments

add comment