The expansion of the Benedictine monastery

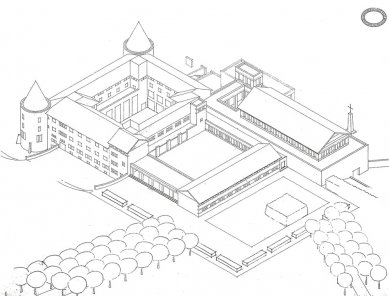

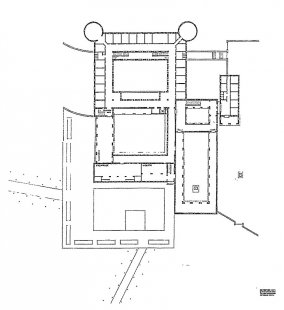

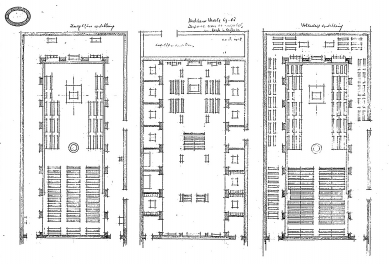

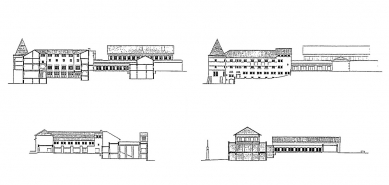

The St. Benedict Monastery is located in southern Netherlands, close to the German border. It was built for monks from Merkelbeek, the first Benedictine institution in the Netherlands after the Reformation. The construction, designed by the renowned architect of sacred buildings, Dominikus Böhm, began in 1922. The author follows the traditional plan of Benedictine monasteries. The work is characterized by its two oval towers that frame the southern facade, while on the northern side there is a church in Romanesque style.

However, right at the beginning, the construction encountered problems – a year after the monks moved in, the work had to be halted due to a lack of funding. Another pause followed during World War II, when even the unfinished monastery served temporarily as barracks for the American army or as housing for families returning from Indonesia. After the war, the complex was assigned to the Oosterhout monastery, whose monks contributed to the completion of the plan. The architect and monk Hans van der Laan was commissioned to develop the proposal for the completion – that is, the church, the addition of a library, a sacristy, and an open arcade around the new monastery.

When Van der Laan arrived on site, he saw a simple brick building in a historicizing style, where all parts of the monastery were tightly knit around a central courtyard. Van der Laan's reconstruction and conversion replaced the original spaces with "cleansed" areas, designed according to his theories. Thus, abandoning romantic forms and oval towers, he instead added a low columned vestibule on the north side and opened the southern part at the location of the refectory.

The work took another thirty years to complete. During this time, Van der Laan matured as a man, monk, and architect. The monastery became an opportunity for him to apply his theories and verify them daily and under all circumstances.

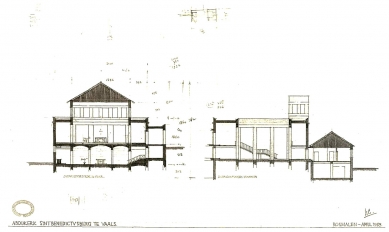

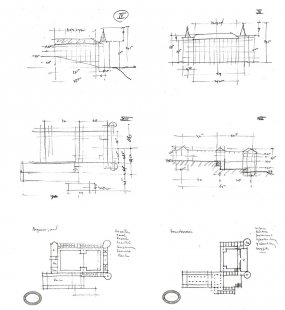

Crypt. It was completed in 1961 and thus became the place where the rebirth of the Vaals monastery began. It is located below ground level and offers both a suggestive and austere space, whose atmosphere is created by the basic means of architecture, namely light, scale, and rhythm. The rectangular floor plan is enlivened by double columns near the side walls, which both define the space of the side chapels and further in the nave provide support for the church above the crypt.

As throughout the building, the materials used are clearly acknowledged: the brick columns are roughly plastered, and the beams are of reinforced concrete. The floor is made up of large slabs of a mixture of cement and river pebbles. The only exception in the extreme simplicity of the whole is the rear wall, which consists of stone slabs. Behind them rest the patrons of the monastery. Their names are engraved on the slabs in a font designed by Van der Laan. Stone is also used for the altars in the chapels, with the only ornament being the candlestick, also designed by the monk-architect.

Light is an integral part of the structure, entering the crypt only from the left. The shadows it creates add richness to the space. The effect of light is distinct at the two entrances leading to the crypt – although they are perfectly symmetrical, they seem completely different. This is precisely because of the light that falls upon them. A distinctive feature of the entire Vaals monastery first appears here: a masterful combination of absolutely ordinary elements from which a mysterious and sacred space emerges.

Church. Together with the annex, it was completed in 1967. It consists of several independent parts – the first of which is the entrance, a long low building with a porter’s space and several guest rooms, followed by an open atrium over two floors, which notably resembles the peristyles of Roman villas. Because the expansion of the Vaals monastery is located on a slope, the church itself is higher than the entrance and is thus accessed via stairs in the portico. This is one of the architecturally most interesting features of the entire complex. The atrium is also one of the most impressive places, an “open room” to the sky. It functions as a threshold, a boundary between the public and the cloister. The actual entrance to the church consists of two simple doors. The adjacent doors from the arcade atrium lead into the private areas of the monastery.

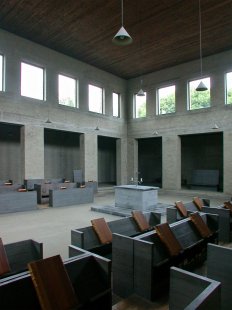

The interior of the church has a basilica floor plan, with the nave surrounded on three sides by a colonnade. The nave acts as an independent structure surrounded by the church. Light enters the church from its upper part, through rectangular windows that converge toward the corners. In the interior, despite the apparent symmetry, many features suggest the exact opposite, for instance, the disharmony of the upper windows with the lower colonnade reminds us that there is no overt formalism used in the building. The sacred atmosphere arises from the overall intertwining of relationships that gives essence to the few elements that the composition consists of.

The altar stands at the end of the nave. On both sides, it is surrounded by two rows of wooden benches, where the monks celebrate the Eucharist. In front of the altar are three additional rows designated for the public. Like all other furnishings of the monastery, the benches were also designed by Van der Laan in the spirit of simplicity, constructed of nailed painted wooden boards, with unique variations. A similar solution – darkly painted wooden boards – is used to cover the ceiling of the nave and colonnades.

The bell tower, a key feature of the monastery's design and prototype for bell towers in Roosenberg and Tomelilli, stands on one side of the entrance peristyle and appears as a small rectangular tower. Its five bells are not tuned as musical instruments but harmonized according to the Pythagorean system, which is the basis for Gregorian chant.

Library and Sacristy. This part of the monastery is located in a separate building with a gabled roof, completed in 1986, thus closing the construction of the Benedictine monastery. The library has a simple rectangular floor plan and occupies two floors. The space is divided by a series of columns into a smaller busy part, where the staircase is located, and a larger section, which contains space for the books and study tables. The two opposing staircases are a gem of the entire work. The form they share with the gallery is repeated as in the staircase leading to the church, which is also emphasized by the use of the same materials. The sacristy is also divided – this time evenly – by a series of columns, creating an atmosphere of a square or street, a solution Van der Laan constantly uses in his interiors. It is a large single-story room that holds the items of ceremony and liturgical objects, which were also designed by Van der Laan.

Monastery and Open Arcade. The upper monastery in Vaals is the core of the new expansion, its form unfolding from skillful combinations of elements – the already existing center of the monastery, the new church, the building with the library and sacristy. The arcades run around two sides and feature large windows overlooking the green area in the center. On their third side (the fourth has the original wing of the monastery), the final architectural form discovered in Vaals by Van der Laan appears: a wide, open arcade that forms a sieve between the interior and exterior but also reflects the play of their interrelations.

In Vaals, every detail was designed with respect to the needs of the monks and equally with respect for Benedictine tradition. As can be seen, the entire complex is based on extreme cleanliness, and the spaces arise precisely from the properties of the structural system and used materials. Each function is precisely defined; the busy spaces of the staircases differ from those for the church or library. The choice of materials matches their nature – brick walls and columns "smudged" with mortar, reinforced concrete beams, floors made of a mixture of cement and pebbles, windows of sheet glass, ceilings covered with wooden boards, and granite altars and memorial slabs. Everything is interconnected by a network of proportions that completes the invisible scale of the building. It is both simple and complex, deserving to be appreciated as a modern architectural masterpiece.

The architect also controls the exterior, which is similar to the space in the building. Here too, clear relationships are established between the trees and the existing forest, the vegetable garden, and the path for the monks. Van der Laan imitates the urban landscape, in which trees represent rows of houses and lawns represent squares. One of them is also the monks' cemetery, where graves are arranged in a semicircle and marked only by a simple stone. Monk and architect Van der Laan is also buried here.

However, right at the beginning, the construction encountered problems – a year after the monks moved in, the work had to be halted due to a lack of funding. Another pause followed during World War II, when even the unfinished monastery served temporarily as barracks for the American army or as housing for families returning from Indonesia. After the war, the complex was assigned to the Oosterhout monastery, whose monks contributed to the completion of the plan. The architect and monk Hans van der Laan was commissioned to develop the proposal for the completion – that is, the church, the addition of a library, a sacristy, and an open arcade around the new monastery.

When Van der Laan arrived on site, he saw a simple brick building in a historicizing style, where all parts of the monastery were tightly knit around a central courtyard. Van der Laan's reconstruction and conversion replaced the original spaces with "cleansed" areas, designed according to his theories. Thus, abandoning romantic forms and oval towers, he instead added a low columned vestibule on the north side and opened the southern part at the location of the refectory.

The work took another thirty years to complete. During this time, Van der Laan matured as a man, monk, and architect. The monastery became an opportunity for him to apply his theories and verify them daily and under all circumstances.

Crypt. It was completed in 1961 and thus became the place where the rebirth of the Vaals monastery began. It is located below ground level and offers both a suggestive and austere space, whose atmosphere is created by the basic means of architecture, namely light, scale, and rhythm. The rectangular floor plan is enlivened by double columns near the side walls, which both define the space of the side chapels and further in the nave provide support for the church above the crypt.

As throughout the building, the materials used are clearly acknowledged: the brick columns are roughly plastered, and the beams are of reinforced concrete. The floor is made up of large slabs of a mixture of cement and river pebbles. The only exception in the extreme simplicity of the whole is the rear wall, which consists of stone slabs. Behind them rest the patrons of the monastery. Their names are engraved on the slabs in a font designed by Van der Laan. Stone is also used for the altars in the chapels, with the only ornament being the candlestick, also designed by the monk-architect.

Light is an integral part of the structure, entering the crypt only from the left. The shadows it creates add richness to the space. The effect of light is distinct at the two entrances leading to the crypt – although they are perfectly symmetrical, they seem completely different. This is precisely because of the light that falls upon them. A distinctive feature of the entire Vaals monastery first appears here: a masterful combination of absolutely ordinary elements from which a mysterious and sacred space emerges.

Church. Together with the annex, it was completed in 1967. It consists of several independent parts – the first of which is the entrance, a long low building with a porter’s space and several guest rooms, followed by an open atrium over two floors, which notably resembles the peristyles of Roman villas. Because the expansion of the Vaals monastery is located on a slope, the church itself is higher than the entrance and is thus accessed via stairs in the portico. This is one of the architecturally most interesting features of the entire complex. The atrium is also one of the most impressive places, an “open room” to the sky. It functions as a threshold, a boundary between the public and the cloister. The actual entrance to the church consists of two simple doors. The adjacent doors from the arcade atrium lead into the private areas of the monastery.

The interior of the church has a basilica floor plan, with the nave surrounded on three sides by a colonnade. The nave acts as an independent structure surrounded by the church. Light enters the church from its upper part, through rectangular windows that converge toward the corners. In the interior, despite the apparent symmetry, many features suggest the exact opposite, for instance, the disharmony of the upper windows with the lower colonnade reminds us that there is no overt formalism used in the building. The sacred atmosphere arises from the overall intertwining of relationships that gives essence to the few elements that the composition consists of.

The altar stands at the end of the nave. On both sides, it is surrounded by two rows of wooden benches, where the monks celebrate the Eucharist. In front of the altar are three additional rows designated for the public. Like all other furnishings of the monastery, the benches were also designed by Van der Laan in the spirit of simplicity, constructed of nailed painted wooden boards, with unique variations. A similar solution – darkly painted wooden boards – is used to cover the ceiling of the nave and colonnades.

The bell tower, a key feature of the monastery's design and prototype for bell towers in Roosenberg and Tomelilli, stands on one side of the entrance peristyle and appears as a small rectangular tower. Its five bells are not tuned as musical instruments but harmonized according to the Pythagorean system, which is the basis for Gregorian chant.

Library and Sacristy. This part of the monastery is located in a separate building with a gabled roof, completed in 1986, thus closing the construction of the Benedictine monastery. The library has a simple rectangular floor plan and occupies two floors. The space is divided by a series of columns into a smaller busy part, where the staircase is located, and a larger section, which contains space for the books and study tables. The two opposing staircases are a gem of the entire work. The form they share with the gallery is repeated as in the staircase leading to the church, which is also emphasized by the use of the same materials. The sacristy is also divided – this time evenly – by a series of columns, creating an atmosphere of a square or street, a solution Van der Laan constantly uses in his interiors. It is a large single-story room that holds the items of ceremony and liturgical objects, which were also designed by Van der Laan.

Monastery and Open Arcade. The upper monastery in Vaals is the core of the new expansion, its form unfolding from skillful combinations of elements – the already existing center of the monastery, the new church, the building with the library and sacristy. The arcades run around two sides and feature large windows overlooking the green area in the center. On their third side (the fourth has the original wing of the monastery), the final architectural form discovered in Vaals by Van der Laan appears: a wide, open arcade that forms a sieve between the interior and exterior but also reflects the play of their interrelations.

In Vaals, every detail was designed with respect to the needs of the monks and equally with respect for Benedictine tradition. As can be seen, the entire complex is based on extreme cleanliness, and the spaces arise precisely from the properties of the structural system and used materials. Each function is precisely defined; the busy spaces of the staircases differ from those for the church or library. The choice of materials matches their nature – brick walls and columns "smudged" with mortar, reinforced concrete beams, floors made of a mixture of cement and pebbles, windows of sheet glass, ceilings covered with wooden boards, and granite altars and memorial slabs. Everything is interconnected by a network of proportions that completes the invisible scale of the building. It is both simple and complex, deserving to be appreciated as a modern architectural masterpiece.

The architect also controls the exterior, which is similar to the space in the building. Here too, clear relationships are established between the trees and the existing forest, the vegetable garden, and the path for the monks. Van der Laan imitates the urban landscape, in which trees represent rows of houses and lawns represent squares. One of them is also the monks' cemetery, where graves are arranged in a semicircle and marked only by a simple stone. Monk and architect Van der Laan is also buried here.

A. Ferlenga, P. Verde: Dom Hans Van Der Laan, Architectura & Natura 2011, pp. 52-55

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

5 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

skvĕlé

Pavel Nasadil

11.01.13 10:01

raw

Petr Šmídek

11.01.13 11:08

RO

Pavel Nasadil

12.01.13 10:04

Rudolf Olgiati byl Valeriův otec

Petr Šmídek

12.01.13 11:42

Krásná práce

Jiří Schmidt

12.01.13 02:06

show all comments