Competition proposal for the Academic Square in Brno

The new competition for the placement of the Supreme Court building on the area known as the Academic Square has prompted new considerations about the proper or improper resolution of this square — and since all the negative aspects of this regulation were associated with me as the designer of the Academic Square and university buildings, I feel it necessary to take a stance on the various views of some Brno architects, whether published in daily newspapers or asserted in the so-called regulatory assembly.

To make the matter completely clear, it is good to revisit the emergence of the final form of this square, which has been so ruthlessly suppressed by certain architects for some time. On May 15, 1923, a decision was made regarding the competition for the development and regulatory solution of the Kraví hory area and the so-called academic quarter. A whole series of projects were submitted, and the first prize was awarded to the project by engineer Lamla and architect Grunt. This project also served as the basis for further regulatory solutions. When the Ministry of Public Works wanted to announce a second competition for a substantive solution for all university buildings, it requested through the provincial office in Brno from the city regulatory office final proposals for the regulation of this area. These proposals were developed by the city regulatory office, where the leading designer at that time was architect Kumpošt, and after the approval of these proposals by the so-called regulatory assembly, the regulation proposal was handed over to the provincial office to serve as a basis for a public competition, which was to resolve, based on precise programs, in addition to the pavilions for the faculties of law, philosophy, and natural sciences, also the central building for the rectorate and university library, as well as the building for the state conservatory.

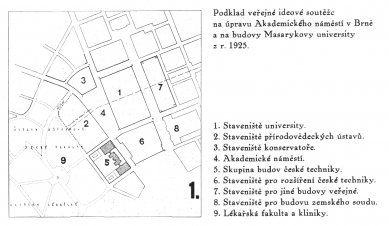

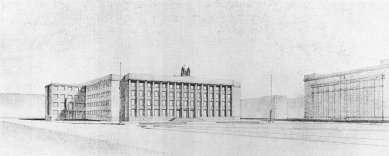

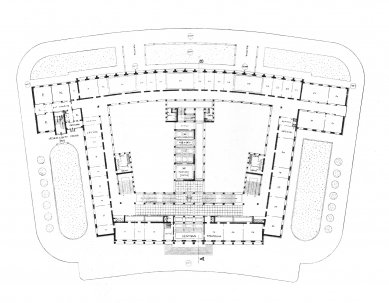

With this regulation proposal, which was given as the basis for the competition — the triangular shape of the Academic Square was already fixed [see figure 1], and the competing architects had a rather thankless task of giving this square an architectural form.

In the competition, there were also proposals that left the Academic Square with the simple shape of a triangle, thus maintaining the form of the established regulation without architectural solution. However, all three awarded proposals fundamentally addressed the square in the same way, namely by dividing the longer sides of the square into three parts, of which the middle, largest part retreats somewhat backwards, which makes the square architecturally more articulated and the divergence of both its longer sides more tolerable.

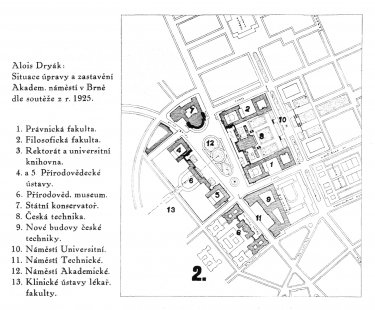

The certain difficulties posed by the triangular shape of the square were certainly fully recognized by all the architects who participated in that competition, but the task was set, and the competition was to solve it. My project received the best recognition in this competition not only in terms of the floor plans of the individual buildings but also from a regulatory perspective [see figure 2]. The task was simplified in the competition by the fact that all the buildings surrounding the Academic Square were designed by a single architect and that both longer façades were occupied by university buildings, which were approximately of the same type, the same size, and thus of the same architecture; the central building of the conservatory provided a distinct central and primary motif for the square with its concert hall, since all these buildings were designed and uniformly resolved by one and the same architect, and all the buildings together were thus mutually balanced, so that what the square loses in tranquility due to the divergence of the side façades it gains back in uniform architectural design and material balancing. And that is very important in this case.

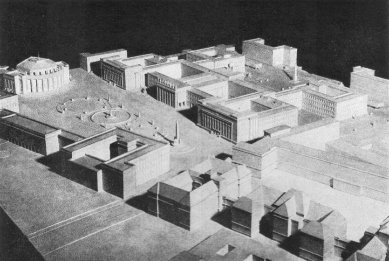

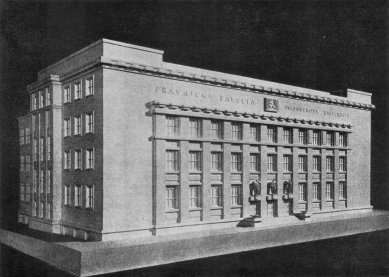

In the final proposal, in agreement with the regulatory office, the overall length of the square was shortened by 20 m — and on the occasion of the exhibition of contemporary culture in Brno, a model of the entire square and the entire complex of all university buildings was developed, from which everyone, not only experts but also laypeople, could easily assess the appropriateness of the buildings to the size of the square — and everyone, even laypeople, would surely agree that there is no disproportion or over-dimensioning of the square in relation to the buildings. The dimensions of the university buildings are considerable, but they are justified by the precise program defined by the professorial council and approved by the Ministry of Education and National Enlightenment. These extensive objects also require a correspondingly large square, i.e., a space that provides sufficient distance and overview. To limit the square to 160 m in front of a building whose main façade has a total length of 270 m would be senseless.

And yet, some architects from Brno are trying to prove the inadequacy and disproportion of the square — and for that purpose, they have published graphic studies, which can mostly be classified as attempts that are less successful or even unsuccessful.

Thus, architect Fuchs published a study in Index - in which he essentially retains the same triangular shape of the square, but extends the triangle to the health insurance office, denying any possibility of architectural resolution of the area and proposing a free park arrangement without any form. Such an arrangement can always be implemented easily and quickly by simply leaving everything to chance.

Architect Kroha also retains the fundamentally diverging shape of the square, but does not recognize the necessity of balancing both longer walls of the square to a single axis and proposes several skyscrapers on the western side along Veveří Street for the purposes of Czech technology, thereby completely violating the weight balance of the materials concerning the given and only axis of the square.

In the second narrower competition for the Supreme Court building, on the contrary, all designers, with one exception, adhered to the given basic shape of the square [which was, after all, a condition of this competition], only architect Wiesner dared a completely gratuitous deviation, creating a rectangular square [which, of course, intersects the main communication almost diagonally], significantly enlarging the square towards Kraví hory without regard to the conditions of the existing terrain and shaping the square without consideration of the existing old building of Czech technology, and even without regard to the newly designed building of the university, for which the Academic Square was actually created. Architect Wiesner's proposal does not stand after careful consideration and praise from Mr. O. Schürer in the objective professional assessment in Lidové noviny from October 7, 1931, just as it was duly condemned by the jury.

In issue 565 of Lidové noviny, architect Liebscher published another study. To him, too, the Academic Square is too large and therefore he reduces it by building a smaller object in front of the main façade of the faculty of law and a larger object [the Supreme Court building] in front of the proposed faculty of philosophy, thereby significantly shortening the square from 280 m to 160 m, but in order to fit this smaller block in front of the law faculty, he expands the entire square towards Kraví hory by 12 m, thus altering and turning the main axis of the square by 90° concerning the continuous communication, causing even more unrest. At the same time, he places all the main pavilions of the university and technology faculties into the side streets, thus denying the complete original purpose and designation of the Academic Square, hindering visibility and disorienting the whole layout. At the same time, he is also forced to bend the main outlet communication [Veveří Street] immediately behind Czech technology, where it is also considerably narrowed; accompanying this, architect Liebscher states the main advantage of his solution as savings on construction area. However, upon precise calculation, these savings turn out as follows:

Gains:

A. land for the Supreme Court .. 6,400 m²

B. land for the building in front of the law faculty .. 2,400 m²

C. part of the land for residential buildings behind the Supreme Court building .. 1,650 m²

Total gains 10,450 m²

Losses:

D. by expanding the square in front of the old building of technology .. 2,700 m²

E. by expanding the square towards Kraví hory .. 3,720 m²

Total losses 6,420 m²

Thus, he gains a total of 4,030 m², i.e., about 1,120 square fathoms. However, for this gain, the outlet communication [Veveří Street] will be worsened, and by hiding the main pavilions of the university faculties into the side streets behind the Supreme Court building and the building in front of the law faculty, whose purpose is not yet known, it lacks visibility and the necessary distance for necessary orientation.

Thus, even this proposal presented with such pretension does not withstand strict criticism.

To make the matter completely clear, it is good to revisit the emergence of the final form of this square, which has been so ruthlessly suppressed by certain architects for some time. On May 15, 1923, a decision was made regarding the competition for the development and regulatory solution of the Kraví hory area and the so-called academic quarter. A whole series of projects were submitted, and the first prize was awarded to the project by engineer Lamla and architect Grunt. This project also served as the basis for further regulatory solutions. When the Ministry of Public Works wanted to announce a second competition for a substantive solution for all university buildings, it requested through the provincial office in Brno from the city regulatory office final proposals for the regulation of this area. These proposals were developed by the city regulatory office, where the leading designer at that time was architect Kumpošt, and after the approval of these proposals by the so-called regulatory assembly, the regulation proposal was handed over to the provincial office to serve as a basis for a public competition, which was to resolve, based on precise programs, in addition to the pavilions for the faculties of law, philosophy, and natural sciences, also the central building for the rectorate and university library, as well as the building for the state conservatory.

With this regulation proposal, which was given as the basis for the competition — the triangular shape of the Academic Square was already fixed [see figure 1], and the competing architects had a rather thankless task of giving this square an architectural form.

In the competition, there were also proposals that left the Academic Square with the simple shape of a triangle, thus maintaining the form of the established regulation without architectural solution. However, all three awarded proposals fundamentally addressed the square in the same way, namely by dividing the longer sides of the square into three parts, of which the middle, largest part retreats somewhat backwards, which makes the square architecturally more articulated and the divergence of both its longer sides more tolerable.

The certain difficulties posed by the triangular shape of the square were certainly fully recognized by all the architects who participated in that competition, but the task was set, and the competition was to solve it. My project received the best recognition in this competition not only in terms of the floor plans of the individual buildings but also from a regulatory perspective [see figure 2]. The task was simplified in the competition by the fact that all the buildings surrounding the Academic Square were designed by a single architect and that both longer façades were occupied by university buildings, which were approximately of the same type, the same size, and thus of the same architecture; the central building of the conservatory provided a distinct central and primary motif for the square with its concert hall, since all these buildings were designed and uniformly resolved by one and the same architect, and all the buildings together were thus mutually balanced, so that what the square loses in tranquility due to the divergence of the side façades it gains back in uniform architectural design and material balancing. And that is very important in this case.

In the final proposal, in agreement with the regulatory office, the overall length of the square was shortened by 20 m — and on the occasion of the exhibition of contemporary culture in Brno, a model of the entire square and the entire complex of all university buildings was developed, from which everyone, not only experts but also laypeople, could easily assess the appropriateness of the buildings to the size of the square — and everyone, even laypeople, would surely agree that there is no disproportion or over-dimensioning of the square in relation to the buildings. The dimensions of the university buildings are considerable, but they are justified by the precise program defined by the professorial council and approved by the Ministry of Education and National Enlightenment. These extensive objects also require a correspondingly large square, i.e., a space that provides sufficient distance and overview. To limit the square to 160 m in front of a building whose main façade has a total length of 270 m would be senseless.

And yet, some architects from Brno are trying to prove the inadequacy and disproportion of the square — and for that purpose, they have published graphic studies, which can mostly be classified as attempts that are less successful or even unsuccessful.

Thus, architect Fuchs published a study in Index - in which he essentially retains the same triangular shape of the square, but extends the triangle to the health insurance office, denying any possibility of architectural resolution of the area and proposing a free park arrangement without any form. Such an arrangement can always be implemented easily and quickly by simply leaving everything to chance.

Architect Kroha also retains the fundamentally diverging shape of the square, but does not recognize the necessity of balancing both longer walls of the square to a single axis and proposes several skyscrapers on the western side along Veveří Street for the purposes of Czech technology, thereby completely violating the weight balance of the materials concerning the given and only axis of the square.

In the second narrower competition for the Supreme Court building, on the contrary, all designers, with one exception, adhered to the given basic shape of the square [which was, after all, a condition of this competition], only architect Wiesner dared a completely gratuitous deviation, creating a rectangular square [which, of course, intersects the main communication almost diagonally], significantly enlarging the square towards Kraví hory without regard to the conditions of the existing terrain and shaping the square without consideration of the existing old building of Czech technology, and even without regard to the newly designed building of the university, for which the Academic Square was actually created. Architect Wiesner's proposal does not stand after careful consideration and praise from Mr. O. Schürer in the objective professional assessment in Lidové noviny from October 7, 1931, just as it was duly condemned by the jury.

In issue 565 of Lidové noviny, architect Liebscher published another study. To him, too, the Academic Square is too large and therefore he reduces it by building a smaller object in front of the main façade of the faculty of law and a larger object [the Supreme Court building] in front of the proposed faculty of philosophy, thereby significantly shortening the square from 280 m to 160 m, but in order to fit this smaller block in front of the law faculty, he expands the entire square towards Kraví hory by 12 m, thus altering and turning the main axis of the square by 90° concerning the continuous communication, causing even more unrest. At the same time, he places all the main pavilions of the university and technology faculties into the side streets, thus denying the complete original purpose and designation of the Academic Square, hindering visibility and disorienting the whole layout. At the same time, he is also forced to bend the main outlet communication [Veveří Street] immediately behind Czech technology, where it is also considerably narrowed; accompanying this, architect Liebscher states the main advantage of his solution as savings on construction area. However, upon precise calculation, these savings turn out as follows:

Gains:

A. land for the Supreme Court .. 6,400 m²

B. land for the building in front of the law faculty .. 2,400 m²

C. part of the land for residential buildings behind the Supreme Court building .. 1,650 m²

Total gains 10,450 m²

Losses:

D. by expanding the square in front of the old building of technology .. 2,700 m²

E. by expanding the square towards Kraví hory .. 3,720 m²

Total losses 6,420 m²

Thus, he gains a total of 4,030 m², i.e., about 1,120 square fathoms. However, for this gain, the outlet communication [Veveří Street] will be worsened, and by hiding the main pavilions of the university faculties into the side streets behind the Supreme Court building and the building in front of the law faculty, whose purpose is not yet known, it lacks visibility and the necessary distance for necessary orientation.

Thus, even this proposal presented with such pretension does not withstand strict criticism.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment