Vila Schwob

The Turkish Villa

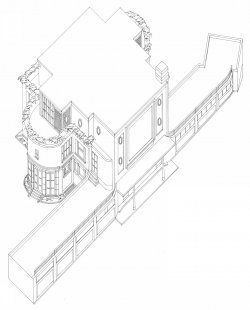

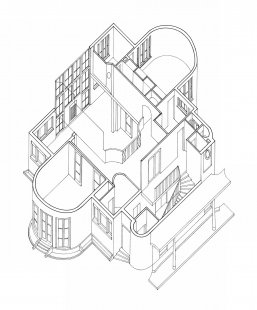

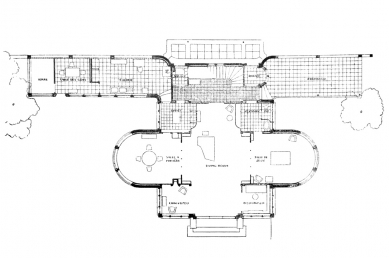

While Villa Fallet was the very first building designed by Jeanneret, which he created in collaboration with his teacher René Chapallaz, La Maison Blance, intended for his parents, was already his first independent realization, where he richly utilized insights from his study trips. However, the first house that Le Corbusier publicly acknowledged, published in the magazine L'Esprit Nouveau and included in an extensive eight-part monograph, was the representative Schwob villa for a wealthy watch manufacturer. The villa on the Pouillerel hill is also nicknamed “Turkish,” as the project arose during Jeanneret's travels in Turkey. The Schwob villa was also Le Corbusier's last realization in his hometown. It is also the first use of reinforced concrete skeleton for a family building in Europe. Its principles derive from the conceptual project Dom-Ino, which was intended to aid in the post-war reconstruction of Flanders. In the division of the facade, one can trace a reference to Palladio's house “Casa Cogollo” in Vicenza. The reinforced concrete structure reflected the experiences that young Jeanneret gained during his fourteen-month stay (1908-10) in Perret's Paris office, which was one of the first to utilize this rediscovered material in the construction of residential buildings.

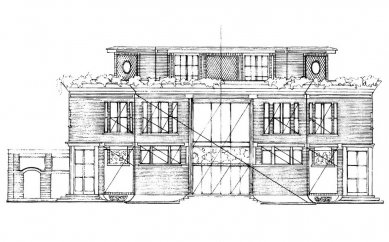

The building reflects a significant shift in Le Corbusier's architectural thinking. It is a hybrid between classical and modern reasoning. On one hand, the design employs traditional symmetrical solutions, but the reinforced concrete structure also provided freedom in the arrangement of internal walls and the division of facades. The covered entrance facade features a pair of symmetrically placed doors: one is the main entrance and the other a service entrance. The brick wall delineating the northern boundary of the property flows smoothly from the mass of the house, creating a gradual transition to the garden. The house features central heating embedded in the walls and floors. Large glazed areas, an expansive roof terrace, and a garden pergola suggest that the ochre brick house is more likely found in the Mediterranean than in the Alpine environment.

The building reflects a significant shift in Le Corbusier's architectural thinking. It is a hybrid between classical and modern reasoning. On one hand, the design employs traditional symmetrical solutions, but the reinforced concrete structure also provided freedom in the arrangement of internal walls and the division of facades. The covered entrance facade features a pair of symmetrically placed doors: one is the main entrance and the other a service entrance. The brick wall delineating the northern boundary of the property flows smoothly from the mass of the house, creating a gradual transition to the garden. The house features central heating embedded in the walls and floors. Large glazed areas, an expansive roof terrace, and a garden pergola suggest that the ochre brick house is more likely found in the Mediterranean than in the Alpine environment.

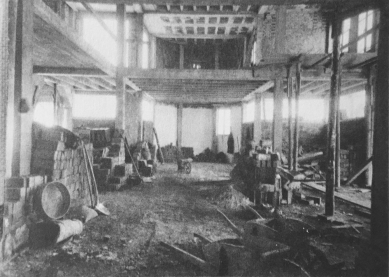

Construction costs soon exceeded the expected price. A freshly thirty-year-old Le Corbusier, after being sued by the investor, went to Paris and first saw the completed house in 1919. The legal proceedings between the architect and the investor ended in June 1920 with an agreement acknowledging a certain degree of responsibility from both parties. In the 1960s, the interior underwent reconstruction by Milanese architect Angelo Mangiarotti, who, however, preserved Jeanneret's spirit. In 1986, the villa was purchased by the watchmaking company Ebel, and after an expensive renovation, it is today used for social and business events, as well as offering residential spaces to select employees and distinguished guests.

Le Corbusier-Saugnier: Villa from 1916

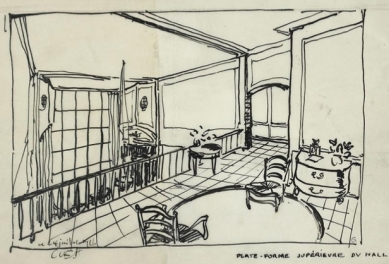

Interesting are the practical tips in the “Manuel de l’habitation”: *) “Design a large hall instead of all salons! Don’t undress in the bedroom! Design a dressing room! Place the kitchen to prevent odors! Use practical furniture, not decorative! Wall cabinets will save space. Put only a few paintings on the walls, but good ones! Store your collections in cabinets (as valuable items). Teach your children that a house is only livable when it has plenty of light, clean, bare walls, and parquet floors! To maintain cleanliness, throw away your oriental carpets and upholstery! Think of the economy of your gestures, orders, and ideas! Praise much smaller rooms than those in which your parents housed you! etc.

Even in urban construction, Le Corbusier-Saugnier promotes his views. In an article**) he opposes curved streets, glorified by Camillo Sitte, which have their origins in the Middle Ages. Thus, picturesque beauty was combined with the rules of urban life. Germany has established entire quarters based on this aesthetics (for there was no other question than aesthetics). In the age of automobiles, this is paradoxical. The modern city lives by laws; practical regulations for waste disposal, sidewalks, carriageways, etc. Every circulation requires laws. This is healthy for the city’s soul. The curve is ruinous, difficult, paralyzing. One must have the courage to admire cities with straight streets in America. A straight street is moral and noble. Examples include the layouts of Antwerp from the 17th century, Paris, Minneapolis, and Washington.

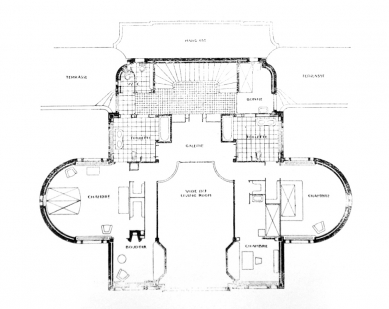

From the works of Le Corbusier-Saugnier, we must mention his ***) designs for housing colonies, slaughterhouse designs, several villas, a terrace house quarter, and a proposal for a million-person city. All designs exploit the constructive possibilities of reinforced concrete to the utmost. They have flat or hipped roofs, cantilevered terraces, and excellent modern layouts. The buildings have bare walls with only open openings; simple geometric shapes; a complete rejection of all decor and a beautiful mass proportion. Of his executed works, the villa from 1916 was reproduced. Its main idea is again constructive; the floor plan combines (in the English manner) all rooms around a hall in the manner of large bay windows. The building has no central walls; all structures are supported by only a few slender pillars. An interesting article by Julien

*) L’esprit nouveau No. 6.

**) L’esprit nouveau No. 17: Le chemin des ânes, le chemin des hommes.

***) L’esprit nouveau No. 6: Wasmuth’s Monatshefte Jahrgang VII., Heft 3-4.

Caron, the accompanying illustration. I will quote only a sample: The formation of shapes in space can only occur through construction. The calculation must guide great architecture; today’s financial, constructive, and technical means provide greater possibilities than in earlier times.

Without full mastery of the qualities of the constructor, the engineer, an architect cannot fully utilize their creative ability. The spirit of truth and the spirit of feeling, refinement, are linked and must work simultaneously from the very choice of location. An artist must not be content with being merely a repairman of the engineer’s work. The artist and scientist in a single person must create simultaneously, but this combination of such diverse talents creates the main cause of the immense difficulty of architecture. Such minds are rare; a person is usually either an engineer, or, driven by feeling, only a decorator; however, none of them is an architect. Architectural conception has the nature of all formative conceptions: it inevitably needs truth (order, construction) and then feeling (a certain lyricism); in architecture, where the necessities of need are pushed to extremes, the problem is further complicated.

Contemporary architecture wanders, which is the fatal consequence of the disruption between opinions deriving from both the intrinsic origin of architecture, i.e., everything that stems from purpose, from construction, derived from disciplined material, and the development of society, as well as from the great constants of formative values, which are eternal because they always and exclusively depend on light and proportion. An example is cited of a window, which must have certain distances and dimensions for a plastic resonance with other windows, with the overall facade; but its proportions and location must also agree with the practical conditions, so foreign to plasticity. It must fulfill a determined function. Creating an organism of high values both plastic and practical is a problem not only for the engineer but also for the architect. The works of architecture are like music; they act directly and with a greater force than works, for example, of painting (which act physically through the reactions they cause). This is the main effect of content; the latter joins: lighting, colors, decor, which is the last. Nowadays architecture is said to be only in decor; the floor plan is just a dull appendage. Reinforced concrete has brought great freedom; but like every freedom, it also brings strict rules, requiring discipline; while allowing the use of large spaces, it imposes precise calculations.

Among Le Corbusier-Saugnier’s collaborators, one should mention Tony Garnier. His project for a garden city in a shared large garden, houses of bare, strict architecture, was reproduced in L’esprit nouveau.

In Art et Décoration*) an article by H. M. Magne appeared in 1919 with numerous, interesting illustrations of bold reinforced concrete structures of industrial enterprises that sprang up in France during the war. Their strict, austere appearance and the boldness of their conception make them in fact the first great realization, at least to a certain extent; works of a new aesthetic. H. M. Magne writes in the article: “As our war was a war of truth, humanity, liberation, so our art must be rational. Our houses, factories, public buildings must be hygienic, comfortable; for it is humane to provide everyone with maximum well-being. We want everything around us to contribute to the art, because the cult of beauty is the best liberation of intellect.” “A new art is being born that will be able to measure itself with the old, because it places all sources of truth in the service of the ideal.” A number of factories and engineering works are reproduced, including: the bridge in Noisiel of reinforced concrete (Saulnier, Moisant, Muller), the power plant in Saint-Ouen (from 1919) with an interesting appearance, reinforced concrete structures, the electrolytic factory in Asnières (from 1918), the workshops of the arsenal in Roanne (from 1917, Boussiron), new docks in Le Havre (from 1918, Andaud, Grandury, Grieu), photographed only the grandiose interior dimensions and impressions, the factory in Caen (from 1918, Freyssinet and Limourin), and finally an attempt at concrete architecture of commerce (architect M. Agache), which, however, is not on par with the aforementioned appearances. There is also an illustration of a concrete “serial house” (Ch. H. Besnard, André Godard), a type manufactured in a factory.

I would like to mention one more work: the design of the memorial to the fallen (Le monument de le tranchée des baïonnettes) by André Ventre, a modern work. Paul Vitry writes in the accompanying article: “In the material and their proportions lies the effect of this architecture. He managed to find a monumental expression that is spontaneously created by material and thought.”14 The work, with the simplest artistic means, devoid of any decor, makes a powerful impact.

It is appropriate, at least partially, to present the opinion expressed by Paul Westheim about modern French architecture.**) We will mention only its most essential parts. He notes that the general impression of French architecture, as much as can be gained from a short visit, is that there is no movement analogous to the so-called new German movement in France until now, even though smaller groups have been organized, like the one recently organized by

*) Year 1914 —19 “L'architecture et les materiaux nouveaux."

**) Wasmuths Monatshefte für Baukunst. Year VII., No. 3—4. “Architektur in Frankreich”.

Dervaux, Léon Bayard and others (from Van and “Quelques Archnecies”)*). This can be explained by the fact that all architectural creation in France is strongly rooted in tradition. There is no sensational upheaval resulting in what nonetheless ultimately is the new German movement. This has protected French architecture from much. It has not entirely succumbed to the individualism that in Germany has been exacerbated by the parvenu mindset of official and unofficial builders. Some see nothing unbearable in having their house built just like their neighbors both to the right and to the left, and as it was done before. With a sense of tact and distance, which has never been lost in France, everyone aligns themselves in the street line. The uniform facade of the block, which in our (in Germany) Walter Curt Behrendt preached as a reform necessity, was not only a program for the Rivoli class, but it seems that it permanently defines the entire image of Paris. Paris remains the most magnificent example of urban construction. Thus, there was no chaos and wildness in France, nor was there the movement that arose in Germany against that wildness.

It seems that in France we have reached the point where conventionality is merely conventionality, where its vital forces do not grow, and it is in increasing contradiction with the needs and foundations of existence of the time. Thus, representative of this situation is Le Corbusier-Saugnier. He cannot (P. W.) be labeled as the leader of a movement, although he possesses to a completely extraordinary degree the qualities of a leader, but there is still not, at least in France, a movement.

Le Corbusier-Saugnier also did not have the opportunity to practically realize his ideas to a vast extent. This is closely related to the fact that today in France there are fewer opportunities for construction than in Germany. Businesses are bad, there is an economic crisis that continues to increase, which also catastrophically depresses the prices of works. Everything that Le Corbusier-Saugnier has created (including a single villa) are designs; pursuing this path is against the French tradition, whereas it belongs to the German one. Among the opinions explaining the movement of purism, Paul Westheim cites, among others, from Jeanneret's works and André Lhote: “The last stage of perfect unchangeable form of the object is the "Standard-Ding". Gradable niceties can create objects of superhuman strength (motors). All engineering creation is consciously and fundamentally tied to rational thinking, clarity of purpose, precision, and economy. “Standard” is the highest goal of the engineer. Architectural creation is, however, reactionary, burdened with outdated ideas, saturated with obsolete, decorative elements. There is a glorification of technical thinking and creation. Today is the time of construction. He writes that in Germany the beauty of engineering form is no discovery.

Van de Velde pointed out twenty years ago the beauty of engineering form. He also recalls Loos and quotes the Russian Mesnil: “Fanatical admiration of the machine is altogether futuristic and arises from the pre-industrialized civilization brought by capitalism in its last phase of development and its consequence, materialism in a non-philosophical sense. Italian futurists are more logical than Tatlin when they marry nationalist imperialism and love for war for the sake of war. The pyrotechnic poems of Marinetti resonate completely with the quintessence of Tatlin's machines.”

In response to Le Corbusier-Saugnier’s views, he also quotes Pölzig’s statements.**) Le Corbusier-Saugnier is said to know, as he expressed in conversation, that the ideas he advocates were not unknown in Germany, but the Germans are said to have quickly diluted them; a certain part of architects, the so-called art-industrial ones—have arrived at hollow forms. Theoretically radical, but in practice otherwise. He emphasizes that Le Corbusier-Saugnier does not merely remain in the plains of pure utilitarian form. He does not want to be satisfied only with what the engineer has created as a technical necessity. He wants more. He wants to create. To create as an artist. An engineer creates a Standard when he finds the least intrusive, most usable, economical solution for a specific purpose. Le Corbusier-Saugnier wants architecture, he wants visual appearance, he wants what cubist painters want, who rely on spirit, logic, mathematical laws: he wants harmony of fundamental shape values.

The impetus for this article was recent expressions of representatives of modern efforts in Dutch, German, and French architecture. Its aim was not to provide a complete historical overview of the development of modern architecture in these nations, but to indicate the development of opinions from the first programs to the mentioned expressions, to hint at the paths taken and what principles have determined and determine it. In doing so, the opinions of American Frank Lloyd Wright were also mentioned for their relevance to the mentioned topics and for their significant influence on Europe.

Fifteen to twenty years of the mentioned development is an effort towards spiritualizing programs that were initially too rationalistic and an effort to find parallel paths with modern painting and sculpture. The paths to this have so far diverged significantly. The feeling of today's era seems to be returning to the principles that founded modern

*) According to private reports, Temporal organizes: “Guilde du bâtiment”. Also the Franco-American Society for Urban Construction.

**) See No. 7 “Stavby”; Opinions on modern architecture I.

architecture, but in a transferred, higher, spiritual sense. In a time of great turmoil and confusion in our architecture, there is certainly a felt need to look into the grand, world stage, to overlook the paths taken there, so that our relation to European feeling may be sensed.

Among the efforts of other nations, which had a considerable influence on the beginnings of a fundamentally unified modern movement in the three mentioned nations, the English efforts deserve the greatest attention. Not only the previously mentioned “Arts and Crafts” movement, as a catalyst, but also the ways of applying tradition in modern English architecture and a certain romanticism of this entire movement had a significant influence on Europe, perhaps partly positively by indicating possibilities, but also partly negatively. The English works on the problem of city building, their solutions for garden cities, and all their reform housing efforts are of great importance for the overall development of modern architecture. All of this would require special studies. There are also known efforts, albeit scattered, among Finns, Danes, Swedes, Italians, and some followers of Wright in America. And certainly, a fruitful study would be the tracing of revival efforts in architecture, even if still weak among South Slavs, Poles, and Russians.

Today's efforts in modern architecture, whether Dutch or French, are certainly not a reaction, a return to the times of H. P. Berlage, but a deepening of those earlier ideas and principles and their implementation in harmony with the shape feeling of the time. It is evident that what characterizes modern architecture in foreign nations cannot simply be adopted by us, even if many conditions of today's life are also similar to ours; nevertheless, differing circumstances and ways of life, different climates and materials, even different levels of artistic feeling, require different creations, even for the same principles. For example, take flat roofs of residential buildings or the question: bare or plastered walls.

The developmental line of Czech modern architecture is not straight; historicalism and romanticism, folk art, and foreign influences in this sense affect its deviations. It seems that this developmental line is not only straightening out abroad but also among us. Post-war romanticism is subsiding. The new significant social tasks are primarily those that occupy the hearts and minds of architects. All previous efforts among us primarily took on an individual form, with their multiplication, relations, and rhythm; but the fundamental principles of modern architecture remained aside. Perhaps this time of development enriches the forming possibilities of the future and perhaps it had to be traversed; but it is necessary to set a great goal and pursue it along a large, straight line. And the encouragement and first step to this must also be a look into the world and the study of the development of modern architecture within it. And Czech architecture need not fear that it will lose its own character if it wishes to align with foreign countries; if it has strong personalities, the national character of their work will manifest itself without compulsion.

When a year ago the magazine “Stavba” was being named, it was simultaneously thought of as its program. “Stavba” not only as a completed work but also as creation. Constructive, not decorative art, concurrent with the world's sense of the time, based on modern science, modern construction, and the formative feeling of modern man was the content of this program; art alive, real life, and for life; art not glued onto old schemes but creating boldly, courageously in a new spirit, as bold and courageous as today’s technique, new works for a new era and for new people.

Interesting are the practical tips in the “Manuel de l’habitation”: *) “Design a large hall instead of all salons! Don’t undress in the bedroom! Design a dressing room! Place the kitchen to prevent odors! Use practical furniture, not decorative! Wall cabinets will save space. Put only a few paintings on the walls, but good ones! Store your collections in cabinets (as valuable items). Teach your children that a house is only livable when it has plenty of light, clean, bare walls, and parquet floors! To maintain cleanliness, throw away your oriental carpets and upholstery! Think of the economy of your gestures, orders, and ideas! Praise much smaller rooms than those in which your parents housed you! etc.

Even in urban construction, Le Corbusier-Saugnier promotes his views. In an article**) he opposes curved streets, glorified by Camillo Sitte, which have their origins in the Middle Ages. Thus, picturesque beauty was combined with the rules of urban life. Germany has established entire quarters based on this aesthetics (for there was no other question than aesthetics). In the age of automobiles, this is paradoxical. The modern city lives by laws; practical regulations for waste disposal, sidewalks, carriageways, etc. Every circulation requires laws. This is healthy for the city’s soul. The curve is ruinous, difficult, paralyzing. One must have the courage to admire cities with straight streets in America. A straight street is moral and noble. Examples include the layouts of Antwerp from the 17th century, Paris, Minneapolis, and Washington.

From the works of Le Corbusier-Saugnier, we must mention his ***) designs for housing colonies, slaughterhouse designs, several villas, a terrace house quarter, and a proposal for a million-person city. All designs exploit the constructive possibilities of reinforced concrete to the utmost. They have flat or hipped roofs, cantilevered terraces, and excellent modern layouts. The buildings have bare walls with only open openings; simple geometric shapes; a complete rejection of all decor and a beautiful mass proportion. Of his executed works, the villa from 1916 was reproduced. Its main idea is again constructive; the floor plan combines (in the English manner) all rooms around a hall in the manner of large bay windows. The building has no central walls; all structures are supported by only a few slender pillars. An interesting article by Julien

*) L’esprit nouveau No. 6.

**) L’esprit nouveau No. 17: Le chemin des ânes, le chemin des hommes.

***) L’esprit nouveau No. 6: Wasmuth’s Monatshefte Jahrgang VII., Heft 3-4.

Caron, the accompanying illustration. I will quote only a sample: The formation of shapes in space can only occur through construction. The calculation must guide great architecture; today’s financial, constructive, and technical means provide greater possibilities than in earlier times.

Without full mastery of the qualities of the constructor, the engineer, an architect cannot fully utilize their creative ability. The spirit of truth and the spirit of feeling, refinement, are linked and must work simultaneously from the very choice of location. An artist must not be content with being merely a repairman of the engineer’s work. The artist and scientist in a single person must create simultaneously, but this combination of such diverse talents creates the main cause of the immense difficulty of architecture. Such minds are rare; a person is usually either an engineer, or, driven by feeling, only a decorator; however, none of them is an architect. Architectural conception has the nature of all formative conceptions: it inevitably needs truth (order, construction) and then feeling (a certain lyricism); in architecture, where the necessities of need are pushed to extremes, the problem is further complicated.

Contemporary architecture wanders, which is the fatal consequence of the disruption between opinions deriving from both the intrinsic origin of architecture, i.e., everything that stems from purpose, from construction, derived from disciplined material, and the development of society, as well as from the great constants of formative values, which are eternal because they always and exclusively depend on light and proportion. An example is cited of a window, which must have certain distances and dimensions for a plastic resonance with other windows, with the overall facade; but its proportions and location must also agree with the practical conditions, so foreign to plasticity. It must fulfill a determined function. Creating an organism of high values both plastic and practical is a problem not only for the engineer but also for the architect. The works of architecture are like music; they act directly and with a greater force than works, for example, of painting (which act physically through the reactions they cause). This is the main effect of content; the latter joins: lighting, colors, decor, which is the last. Nowadays architecture is said to be only in decor; the floor plan is just a dull appendage. Reinforced concrete has brought great freedom; but like every freedom, it also brings strict rules, requiring discipline; while allowing the use of large spaces, it imposes precise calculations.

Among Le Corbusier-Saugnier’s collaborators, one should mention Tony Garnier. His project for a garden city in a shared large garden, houses of bare, strict architecture, was reproduced in L’esprit nouveau.

In Art et Décoration*) an article by H. M. Magne appeared in 1919 with numerous, interesting illustrations of bold reinforced concrete structures of industrial enterprises that sprang up in France during the war. Their strict, austere appearance and the boldness of their conception make them in fact the first great realization, at least to a certain extent; works of a new aesthetic. H. M. Magne writes in the article: “As our war was a war of truth, humanity, liberation, so our art must be rational. Our houses, factories, public buildings must be hygienic, comfortable; for it is humane to provide everyone with maximum well-being. We want everything around us to contribute to the art, because the cult of beauty is the best liberation of intellect.” “A new art is being born that will be able to measure itself with the old, because it places all sources of truth in the service of the ideal.” A number of factories and engineering works are reproduced, including: the bridge in Noisiel of reinforced concrete (Saulnier, Moisant, Muller), the power plant in Saint-Ouen (from 1919) with an interesting appearance, reinforced concrete structures, the electrolytic factory in Asnières (from 1918), the workshops of the arsenal in Roanne (from 1917, Boussiron), new docks in Le Havre (from 1918, Andaud, Grandury, Grieu), photographed only the grandiose interior dimensions and impressions, the factory in Caen (from 1918, Freyssinet and Limourin), and finally an attempt at concrete architecture of commerce (architect M. Agache), which, however, is not on par with the aforementioned appearances. There is also an illustration of a concrete “serial house” (Ch. H. Besnard, André Godard), a type manufactured in a factory.

I would like to mention one more work: the design of the memorial to the fallen (Le monument de le tranchée des baïonnettes) by André Ventre, a modern work. Paul Vitry writes in the accompanying article: “In the material and their proportions lies the effect of this architecture. He managed to find a monumental expression that is spontaneously created by material and thought.”14 The work, with the simplest artistic means, devoid of any decor, makes a powerful impact.

It is appropriate, at least partially, to present the opinion expressed by Paul Westheim about modern French architecture.**) We will mention only its most essential parts. He notes that the general impression of French architecture, as much as can be gained from a short visit, is that there is no movement analogous to the so-called new German movement in France until now, even though smaller groups have been organized, like the one recently organized by

*) Year 1914 —19 “L'architecture et les materiaux nouveaux."

**) Wasmuths Monatshefte für Baukunst. Year VII., No. 3—4. “Architektur in Frankreich”.

Dervaux, Léon Bayard and others (from Van and “Quelques Archnecies”)*). This can be explained by the fact that all architectural creation in France is strongly rooted in tradition. There is no sensational upheaval resulting in what nonetheless ultimately is the new German movement. This has protected French architecture from much. It has not entirely succumbed to the individualism that in Germany has been exacerbated by the parvenu mindset of official and unofficial builders. Some see nothing unbearable in having their house built just like their neighbors both to the right and to the left, and as it was done before. With a sense of tact and distance, which has never been lost in France, everyone aligns themselves in the street line. The uniform facade of the block, which in our (in Germany) Walter Curt Behrendt preached as a reform necessity, was not only a program for the Rivoli class, but it seems that it permanently defines the entire image of Paris. Paris remains the most magnificent example of urban construction. Thus, there was no chaos and wildness in France, nor was there the movement that arose in Germany against that wildness.

It seems that in France we have reached the point where conventionality is merely conventionality, where its vital forces do not grow, and it is in increasing contradiction with the needs and foundations of existence of the time. Thus, representative of this situation is Le Corbusier-Saugnier. He cannot (P. W.) be labeled as the leader of a movement, although he possesses to a completely extraordinary degree the qualities of a leader, but there is still not, at least in France, a movement.

Le Corbusier-Saugnier also did not have the opportunity to practically realize his ideas to a vast extent. This is closely related to the fact that today in France there are fewer opportunities for construction than in Germany. Businesses are bad, there is an economic crisis that continues to increase, which also catastrophically depresses the prices of works. Everything that Le Corbusier-Saugnier has created (including a single villa) are designs; pursuing this path is against the French tradition, whereas it belongs to the German one. Among the opinions explaining the movement of purism, Paul Westheim cites, among others, from Jeanneret's works and André Lhote: “The last stage of perfect unchangeable form of the object is the "Standard-Ding". Gradable niceties can create objects of superhuman strength (motors). All engineering creation is consciously and fundamentally tied to rational thinking, clarity of purpose, precision, and economy. “Standard” is the highest goal of the engineer. Architectural creation is, however, reactionary, burdened with outdated ideas, saturated with obsolete, decorative elements. There is a glorification of technical thinking and creation. Today is the time of construction. He writes that in Germany the beauty of engineering form is no discovery.

Van de Velde pointed out twenty years ago the beauty of engineering form. He also recalls Loos and quotes the Russian Mesnil: “Fanatical admiration of the machine is altogether futuristic and arises from the pre-industrialized civilization brought by capitalism in its last phase of development and its consequence, materialism in a non-philosophical sense. Italian futurists are more logical than Tatlin when they marry nationalist imperialism and love for war for the sake of war. The pyrotechnic poems of Marinetti resonate completely with the quintessence of Tatlin's machines.”

In response to Le Corbusier-Saugnier’s views, he also quotes Pölzig’s statements.**) Le Corbusier-Saugnier is said to know, as he expressed in conversation, that the ideas he advocates were not unknown in Germany, but the Germans are said to have quickly diluted them; a certain part of architects, the so-called art-industrial ones—have arrived at hollow forms. Theoretically radical, but in practice otherwise. He emphasizes that Le Corbusier-Saugnier does not merely remain in the plains of pure utilitarian form. He does not want to be satisfied only with what the engineer has created as a technical necessity. He wants more. He wants to create. To create as an artist. An engineer creates a Standard when he finds the least intrusive, most usable, economical solution for a specific purpose. Le Corbusier-Saugnier wants architecture, he wants visual appearance, he wants what cubist painters want, who rely on spirit, logic, mathematical laws: he wants harmony of fundamental shape values.

The impetus for this article was recent expressions of representatives of modern efforts in Dutch, German, and French architecture. Its aim was not to provide a complete historical overview of the development of modern architecture in these nations, but to indicate the development of opinions from the first programs to the mentioned expressions, to hint at the paths taken and what principles have determined and determine it. In doing so, the opinions of American Frank Lloyd Wright were also mentioned for their relevance to the mentioned topics and for their significant influence on Europe.

Fifteen to twenty years of the mentioned development is an effort towards spiritualizing programs that were initially too rationalistic and an effort to find parallel paths with modern painting and sculpture. The paths to this have so far diverged significantly. The feeling of today's era seems to be returning to the principles that founded modern

*) According to private reports, Temporal organizes: “Guilde du bâtiment”. Also the Franco-American Society for Urban Construction.

**) See No. 7 “Stavby”; Opinions on modern architecture I.

architecture, but in a transferred, higher, spiritual sense. In a time of great turmoil and confusion in our architecture, there is certainly a felt need to look into the grand, world stage, to overlook the paths taken there, so that our relation to European feeling may be sensed.

Among the efforts of other nations, which had a considerable influence on the beginnings of a fundamentally unified modern movement in the three mentioned nations, the English efforts deserve the greatest attention. Not only the previously mentioned “Arts and Crafts” movement, as a catalyst, but also the ways of applying tradition in modern English architecture and a certain romanticism of this entire movement had a significant influence on Europe, perhaps partly positively by indicating possibilities, but also partly negatively. The English works on the problem of city building, their solutions for garden cities, and all their reform housing efforts are of great importance for the overall development of modern architecture. All of this would require special studies. There are also known efforts, albeit scattered, among Finns, Danes, Swedes, Italians, and some followers of Wright in America. And certainly, a fruitful study would be the tracing of revival efforts in architecture, even if still weak among South Slavs, Poles, and Russians.

Today's efforts in modern architecture, whether Dutch or French, are certainly not a reaction, a return to the times of H. P. Berlage, but a deepening of those earlier ideas and principles and their implementation in harmony with the shape feeling of the time. It is evident that what characterizes modern architecture in foreign nations cannot simply be adopted by us, even if many conditions of today's life are also similar to ours; nevertheless, differing circumstances and ways of life, different climates and materials, even different levels of artistic feeling, require different creations, even for the same principles. For example, take flat roofs of residential buildings or the question: bare or plastered walls.

The developmental line of Czech modern architecture is not straight; historicalism and romanticism, folk art, and foreign influences in this sense affect its deviations. It seems that this developmental line is not only straightening out abroad but also among us. Post-war romanticism is subsiding. The new significant social tasks are primarily those that occupy the hearts and minds of architects. All previous efforts among us primarily took on an individual form, with their multiplication, relations, and rhythm; but the fundamental principles of modern architecture remained aside. Perhaps this time of development enriches the forming possibilities of the future and perhaps it had to be traversed; but it is necessary to set a great goal and pursue it along a large, straight line. And the encouragement and first step to this must also be a look into the world and the study of the development of modern architecture within it. And Czech architecture need not fear that it will lose its own character if it wishes to align with foreign countries; if it has strong personalities, the national character of their work will manifest itself without compulsion.

When a year ago the magazine “Stavba” was being named, it was simultaneously thought of as its program. “Stavba” not only as a completed work but also as creation. Constructive, not decorative art, concurrent with the world's sense of the time, based on modern science, modern construction, and the formative feeling of modern man was the content of this program; art alive, real life, and for life; art not glued onto old schemes but creating boldly, courageously in a new spirit, as bold and courageous as today’s technique, new works for a new era and for new people.

source: Stavba I, pp. 210-214

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment