Vila Tugendhat

The architectural historian Wolf Tegethoff designated the Tugendhat villa together with the Robie House by Frank Lloyd Wright, Steiner House by Adolf Loos, and Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier as key works of modern architecture. His appreciation for the Tugendhat villa stemmed primarily from the free interplay of space and Mies’s formal clarity.

During the 19th century, Brno became the center of textile production in what was then Austria-Hungary. The development of industry also led to a growth in Brno's population, which prompted the construction of new suburbs, including Černá Pole, where the Tugendhat villa is located. The favorable location of Černá Pole relative to the city center and its topographical advantages quickly led to the establishment of one of Brno's prestigious villa districts. The southern slopes above the city park Lužánky, with a beautiful view of the center of Brno, soon became covered with villas. Around the year 1900, a villa in the Art Nouveau style was built at the foot of the southern slope for the Löw-Beer family. When, in 1928, Greta, the daughter of industrialist Löw-Beer, remarried another industrialist, Fritz Tugendhat, she received as a dowry the upper part of the land above the Löw-Beer villa. The preparation for the construction of a new residence could begin; the couple had already contacted the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe through art historian Eduard Fuchs during their stay in Berlin in 1927. The young couple admired the neoclassical house of Eduard Fuchs that Mies was designing. During a visit to the architect, the couple viewed the project for the German pavilion at the World Fair in Barcelona, and Mrs. Tugendhat was so taken with the new style that nothing prevented Mies from traveling to Brno.

Mies arrived in Brno in September 1928 and was captivated by the plot. He immediately began working on the villa project, and by the end of the year, a design already existed that implemented the ideas of the Barcelona pavilion. The construction was realized from July 1929 to the end of 1930, and the Tugendhats moved into the villa in December 1930. The architect's original concerns about possible poor execution of the building were dismissed by the dozen Moravian construction companies that realized the villa under the direction of the Brno construction firm Moritz and Arthur Eisler.

The Brno Tugendhat villa is based in its concept on the ideas of Mies’s Barcelona pavilion from 1927. Informed by Dutch plasticism, Mies created his unmistakable handwriting based on the unity of space, whose flow is restricted only by individual architectural elements mostly executed in the highest quality materials and details.

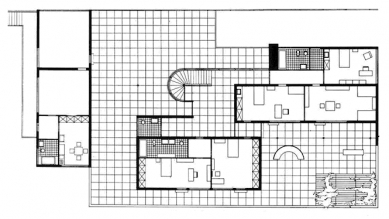

Access to the house is possible from the northern side from Černopolní Street. The relatively unattractive street façade is broken by a direct entrance to the terrace with a magnificent view of the historical center of Brno. The inviting curve of the milk glass leads the visitor into the entrance foyer with a travertine floor, ebony built-in cabinets, and plaster finishes. Even in this space, Mies indicates to us that he is a master of detail (as he used to say - "God is in the details"). Although he does not use many materials, he does so with a generosity that is unique to him. Technical finesse, from the height of the doors to the handrail of the railing, is timeless and enchanting. The Tugendhat villa is proof of the necessity of technical education for an architect. Returning to the entrance foyer, we find that the upper floor of the villa is occupied by the family members' bedrooms with hygienic facilities. The rooms have direct access to the outdoor terrace. From the foyer, one can descend to the lower floor, which is largely filled with a living area comprising a living room, dining room, study, library, and occasionally a home cinema. The living space of the lower floor plays the most important role in the contribution of the Tugendhat villa to the history of world architecture. The central elements of the space are the onyx partition wall and the originally makassar segment that defines the dining area. The southern wall is entirely glazed, allowing for the complete recess of three mega windows into the lower floor. The space not only flows within the interior of the villa but also unites the interior with the exterior. The height level of the living floor and the garden prevents complete merging; however, the feeling of freedom is further enhanced. I do not know whether Mies studied the principles of Feng Shui, but in any case, when you stand in the living room and look into the garden, you understand how the phoenix flies away.

A significant part of the villa consists of technical facilities and service areas. Technical equipment for heating, air conditioning, etc. fills the entire lowest floor, while the service areas occupy a separate part of the house adjacent to the garage and kitchen.

The Tugendhat villa is a top-notch example of extremely comfortable living that impresses even after 70 years. Mies’s timeless concept has dazzled many architects, and it can be stated without scruple that the Tugendhat villa is his landmark work that secured him immortality. Thank goodness it was realized in Brno.

Fritz Tugendhat originally wanted to study medicine, but ultimately he also became involved in the family textile business. As not a particularly gifted businessman, he was more interested in the technical side of things and designing fabrics. In 1928, he married Greta, née Löw-Beer, in Berlin; she came from an even wealthier Jewish entrepreneurial family involved in sugar and distillery industries. Originally, she owned the land on which the young couple decided to build a modern house.

The Tugendhats approached the renowned German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, whose work art-loving Greta Tugendhat had familiarized herself with while living in Berlin. "I really wished to have a modern spacious house with clear and simple shapes. My husband was horrified by rooms full of figurines and doilies, as he knew them from his childhood,” she said. After viewing the plot with its beautiful view of Brno, the architect accepted the commission and created a unique building, Mies’s most important pre-war work.

The Tugendhats moved into the villa in 1930 with their sons Ernest and Herbert and Hanna, Greta's daughter from her first marriage. However, they did not have long to enjoy their new home; after eight years, they had to leave the country due to the growing Nazi threat. The family made it to Venezuela through Switzerland in 1941, where daughters Ruth and Daniela were born. The villa was first confiscated by the Gestapo, then post-war, Soviet soldiers briefly inhabited it, after which it was nationalized.

It served as a dance school and operated as a rehabilitation exercise facility for children. It was not until 1981 that the building underwent its first repairs, preparing it for a historical moment – in 1992, the agreement on the division of Czechoslovakia was signed there. Since 2001, it has been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List, and between 2010 and 2012, it underwent a sensitive reconstruction. Fritz Tugendhat, who died in 1958 in Switzerland, never visited it again; Greta was there twice in the late 1960s.

During the 19th century, Brno became the center of textile production in what was then Austria-Hungary. The development of industry also led to a growth in Brno's population, which prompted the construction of new suburbs, including Černá Pole, where the Tugendhat villa is located. The favorable location of Černá Pole relative to the city center and its topographical advantages quickly led to the establishment of one of Brno's prestigious villa districts. The southern slopes above the city park Lužánky, with a beautiful view of the center of Brno, soon became covered with villas. Around the year 1900, a villa in the Art Nouveau style was built at the foot of the southern slope for the Löw-Beer family. When, in 1928, Greta, the daughter of industrialist Löw-Beer, remarried another industrialist, Fritz Tugendhat, she received as a dowry the upper part of the land above the Löw-Beer villa. The preparation for the construction of a new residence could begin; the couple had already contacted the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe through art historian Eduard Fuchs during their stay in Berlin in 1927. The young couple admired the neoclassical house of Eduard Fuchs that Mies was designing. During a visit to the architect, the couple viewed the project for the German pavilion at the World Fair in Barcelona, and Mrs. Tugendhat was so taken with the new style that nothing prevented Mies from traveling to Brno.

Mies arrived in Brno in September 1928 and was captivated by the plot. He immediately began working on the villa project, and by the end of the year, a design already existed that implemented the ideas of the Barcelona pavilion. The construction was realized from July 1929 to the end of 1930, and the Tugendhats moved into the villa in December 1930. The architect's original concerns about possible poor execution of the building were dismissed by the dozen Moravian construction companies that realized the villa under the direction of the Brno construction firm Moritz and Arthur Eisler.

The Brno Tugendhat villa is based in its concept on the ideas of Mies’s Barcelona pavilion from 1927. Informed by Dutch plasticism, Mies created his unmistakable handwriting based on the unity of space, whose flow is restricted only by individual architectural elements mostly executed in the highest quality materials and details.

Access to the house is possible from the northern side from Černopolní Street. The relatively unattractive street façade is broken by a direct entrance to the terrace with a magnificent view of the historical center of Brno. The inviting curve of the milk glass leads the visitor into the entrance foyer with a travertine floor, ebony built-in cabinets, and plaster finishes. Even in this space, Mies indicates to us that he is a master of detail (as he used to say - "God is in the details"). Although he does not use many materials, he does so with a generosity that is unique to him. Technical finesse, from the height of the doors to the handrail of the railing, is timeless and enchanting. The Tugendhat villa is proof of the necessity of technical education for an architect. Returning to the entrance foyer, we find that the upper floor of the villa is occupied by the family members' bedrooms with hygienic facilities. The rooms have direct access to the outdoor terrace. From the foyer, one can descend to the lower floor, which is largely filled with a living area comprising a living room, dining room, study, library, and occasionally a home cinema. The living space of the lower floor plays the most important role in the contribution of the Tugendhat villa to the history of world architecture. The central elements of the space are the onyx partition wall and the originally makassar segment that defines the dining area. The southern wall is entirely glazed, allowing for the complete recess of three mega windows into the lower floor. The space not only flows within the interior of the villa but also unites the interior with the exterior. The height level of the living floor and the garden prevents complete merging; however, the feeling of freedom is further enhanced. I do not know whether Mies studied the principles of Feng Shui, but in any case, when you stand in the living room and look into the garden, you understand how the phoenix flies away.

A significant part of the villa consists of technical facilities and service areas. Technical equipment for heating, air conditioning, etc. fills the entire lowest floor, while the service areas occupy a separate part of the house adjacent to the garage and kitchen.

The Tugendhat villa is a top-notch example of extremely comfortable living that impresses even after 70 years. Mies’s timeless concept has dazzled many architects, and it can be stated without scruple that the Tugendhat villa is his landmark work that secured him immortality. Thank goodness it was realized in Brno.

The Tugendhat family did not enjoy their famous Brno villa for long

The Brno functionalist villa, built by textile entrepreneur Fritz Tugendhat in the late 1920s, has been on the UNESCO World Heritage List since December 14, 2001, as the eleventh Czech monument. This unique house, designed by the famous architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, is considered a building that set new standards for modern living and is one of the fundamental works of world modern architecture. However, its original owners did not enjoy the villa for long, as they had to flee from the Nazis at the end of the 1930s.Fritz Tugendhat originally wanted to study medicine, but ultimately he also became involved in the family textile business. As not a particularly gifted businessman, he was more interested in the technical side of things and designing fabrics. In 1928, he married Greta, née Löw-Beer, in Berlin; she came from an even wealthier Jewish entrepreneurial family involved in sugar and distillery industries. Originally, she owned the land on which the young couple decided to build a modern house.

The Tugendhats approached the renowned German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, whose work art-loving Greta Tugendhat had familiarized herself with while living in Berlin. "I really wished to have a modern spacious house with clear and simple shapes. My husband was horrified by rooms full of figurines and doilies, as he knew them from his childhood,” she said. After viewing the plot with its beautiful view of Brno, the architect accepted the commission and created a unique building, Mies’s most important pre-war work.

The Tugendhats moved into the villa in 1930 with their sons Ernest and Herbert and Hanna, Greta's daughter from her first marriage. However, they did not have long to enjoy their new home; after eight years, they had to leave the country due to the growing Nazi threat. The family made it to Venezuela through Switzerland in 1941, where daughters Ruth and Daniela were born. The villa was first confiscated by the Gestapo, then post-war, Soviet soldiers briefly inhabited it, after which it was nationalized.

It served as a dance school and operated as a rehabilitation exercise facility for children. It was not until 1981 that the building underwent its first repairs, preparing it for a historical moment – in 1992, the agreement on the division of Czechoslovakia was signed there. Since 2001, it has been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List, and between 2010 and 2012, it underwent a sensitive reconstruction. Fritz Tugendhat, who died in 1958 in Switzerland, never visited it again; Greta was there twice in the late 1960s.

(Czech Press Agency, 13.12.2021)

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Vila Tugendhat Brno- turistická známka No. 1625

AKompas

11.10.08 04:49

show all comments