Store with Retti Candles

Hollein's Shop "Retti" in Vienna

The 32-year-old architect Hans Hollein was awarded the highest architecture prize, the Reynolds Memorial Award 1966, endowed with $25,000, for his design of a small candle shop in Vienna. The international jury of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), responsible for granting the award, expressed its support for the Viennese architect, even though his project was one of the smallest among the 67 projects considered. The jury believed it to be one of the most significant achievements in the field of architecture.As a result of this decision, Hollein's shop Retti was published in the Viennese magazine Bau (Vol. 1966, No. 3), and photos of it were featured in several other global architectural reviews.

Members of the student scientific circle at the Department of Theory and History of Architecture of the Faculty of Civil Engineering at CTU in Prague have been dealing with the questions of creation of "the Third Generation" * for some time, and their recent focus has primarily been on Vienna with its interesting group around the magazine Bau.

An exhibition titled “Appeal,” which began at the Faculty of Civil Engineering in Prague in March 1967, aimed to familiarize the public with the theoretical views of one of the members of this group, Günther Feuerstein. Feuerstein's interesting manifesto “Architecture: Provocation” articulates three postulates of the new movement: architecture as magical space, as a symbol, as provocation.

The essence of Feuerstein’s thoughts can be described as an effort to restore architecture as an art form. It must be understood that this is not a return to pre-functionalist positions but a constructive effort for new artistic experiences in architecture.

To illuminate these efforts, a method of demonstrating them on a specific object was chosen. This work was preceded by reflections on the specificity of architecture as a visual art. The result of these reflections is the understanding of architecture as visual art, whose specificity and goal is space. Such an understanding of the artwork in the field of architecture then demands that we focus on questions of space during analysis. We are aware that the violation of one of the fundamental conditions of structural analysis—ignorance of the object from autopsy—can be justified only by the fact that no one will likely take on this task in the near future, and that there are very few people in our architectural community who know the object from autopsy.

When we observe the relationship of the urban space**, which is co-created by the Retti shop, and the internal (rather, internal) space of the shop, it is clear that there is no superiority of one over the other, but that both are equal. The internal spaces and the urban space are formed according to their own principles. The overall coherence of the work does not particularly manifest itself at this level. It manifests itself at a second level through connection.

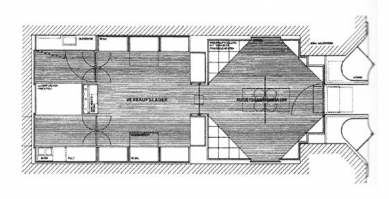

The entire shop is essentially a system of spaces connected to the emphasized depth axis, which is the hallway leading from the entrance into the depth of the building block. This creates a view from the street deep into the space, intentionally undisturbed optically, optically concluded, but perceptible only from a few axial positions. The connection here occurs not only in the optical plane but also in the material plane, which remains unchanged and is the same on the portal*** as inside: shiny, anodized aluminum sheet. Compositionally interesting is that none of the spaces is superior to another, so one cannot infer the shape of the space that will follow from the shape of the portal. The shop portal is a smooth, shiny, opaque surface, which creates a sense of curiosity, even an almost investigative passion. This is amplified by the contrast with the completely glazed neighboring shops, where the compositional intent is an unobstructed view from the street inside, whereas at Retti shop, the visitor is first confronted with a shiny, opaque surface, which does not even hint at what is happening behind it. The only informants about the purpose of the shop are two small showcases, each holding only one candle, turned provocatively towards passersby. To the passerby walking down the street, the only view into the deep shop is limited by the axial area of the narrow entrance hallway. This allows the viewer to see just enough of the shop's interior to spark a desire to enter, to see more.

There are no advertisements or brightly shining neon signs; there is only one word on the wall of the small hallway cutting into the portal: Retti. In red. We suspect that here we stand face to face with provocation. Everything is the opposite of what we are used to. The provocation here seems to be a breach of the scheme, a scheme that seemed to have reached a "civilizational level," a standard. Meanwhile, this scheme has become soulless through its constant repetition. And Hollein's shop directly exposes its neighbors to this soullessness.

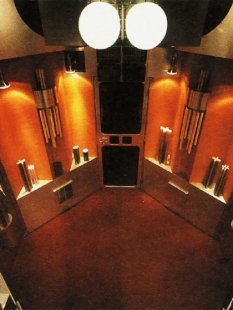

Let us turn our attention to the internal space! What is indeed striking is its area. The total area occupied by the shop is 21 m², the floor area is incredibly small: 14 m². Under certain conditions, such a space would feel cramped, psychologically unbearable. It seems that a certain crampedness would accompany any arrangement. Nevertheless, the internal space does not feel cramped, but rather ceremonial, even monumental. The shiny surface of the walls made of anodized aluminum does not allow for precise focus of the eye on its relatively large homogeneous surfaces. The reflection of displayed objects and the interestingly designed lighting fixture creates the impression of a space vaguely defined, larger than it actually is—and due to its octagonal shape, the reflection on individual walls changes at different speeds with each movement of the viewer.

This concept, supported and shaped by the layout (the narrow hallway suddenly expands into the octagonal exhibition space, which again narrows into the hallway, and then connects to the square sales area, which also serves as a storage), evokes a kind of "pulsation" of space. The space is thus dynamic, even though its dynamism is of a different kind than that of baroque spaces. The feeling of movement in the space, which in baroque space is evoked by the contour lines of spaces, mostly curves of higher than second degree, is here generated by the vague definition of the space through shiny surfaces, the reflections of which, changing with each step, enlarge the actual space and at the same time do not allow us to grasp it clearly and at once.

Perpendicular to the depth axis, Hollein places two mirrors of the same dimensions, facing each other. In the small exhibition octagon, a direct axis is created. The mutual reflections of the reflections lead, in fact, to an apparent repetition of the octagonal exhibition space "behind the mirrors" to infinity. Perpendicular to the depth axis, the real space is "broken by mirrors" into an imaginary space. In contrast to the vague and confusing reflections of the walls, this space is clearly observable and even subjects the viewer to its absurd laws by depicting them in a full sequence toward the vanishing point with diminishing figures. The visible space is observable but inaccessible.

Before the mirrors, several candles are displayed; thanks to the mirrors, we see them from behind as well. This is actually not necessary, as they are perfectly symmetrical, the same from all sides; only their real effectiveness is multiplied by a series of reflections. Others then hang suspended by their wicks, exactly how a candle we use can never be secured. Now we also clearly realize that the entire space is made of synthetic materials and shiny, anodized aluminum. The wax candles are the only "organic," natural material. And their solitude as a natural material in this space is clearly apparent. This is about utilizing the principle of contrast. The connection that the candles create with the space has a taste of absurdity.

Let us note after this observation once again the view through the hallway into the building. What we see at that moment when we pass by the keyhole-like entrance to the shop is not its interior. We see it and actually do not see it: the surfaces that delineate it remain hidden from us. We will see only one thing: a large rectangular showcase with an opalescent back wall, illuminated from an indirect source, and in it several candles, which, being illuminated, appear flat. As we walk down the hallway towards them, we increasingly perceive their inner structure, which resembles the years of wood: longitudinal lines that are the boundaries of individual layers formed during gradual soaking in wax. However, that is an impression up close. From the street, it appears no less strongly, almost attractively: it is calm. Duration, immovable within itself. A fixed point. Here, Hollein utilizes another excellent contrast: we move through a busy shopping street, neon lights restlessly flickering, and suddenly for a brief moment we glimpse, deep within the building, at the end of the loophole-like hallway, a magically glowing showcase. Motion and calm. Here on the street there is movement and perception of the surface of things, which rearrange so quickly that they cannot be well focused on, while on the other side, inside, there is calm and rather than the surface of things, we perceive their inner structure and thus their essence...

The hallway through which we enter leads directly, but halfway through it unexpectedly expands (see the comparison of internal and urban space) into the octagon of the exhibition space. Its quasispherical form suggests that it is a crossroads, albeit an unexpected one. The depth axis of movement here intersects with an imaginary axis. And the intersection is marked by spheres of lighting fixtures.

Here the space itself, by expanding into the octagon, compels us to stop and orient ourselves. It serves as a sort of focal point of the composition: Depth axis - on one side the bustle of the commercial center, the surfaces of things - on the other side calmness, permanence, contemplation of the structure of things, their essence. Multiplicity and uniqueness.

From multiplicity to uniqueness, from surface to essence, from movement to calm, is this not the path of human life?

And the transverse axis, composed of mirrors: imagination - reality - imagination. Is there no imagination without reality and how poor would reality be if it lacked imagination; the focal point of the space, the octagon, would lose all its internal logic, which justifies its existence.

The further continuation of the depth axis leads us into the sales area and thus to the showcase, which was our goal. The journey here ends, but this space simultaneously embodies why this whole work has a real relationship to reality, which might seem almost degrading in the astonishing depth of this artistic creation. However, it is not. In its conception, it represents something that completes the entire composition. It is not a shop as we know it. There is no counter, nor are there the characteristic signs of a self-service store. There is no storage space. The store is the storage itself. Thus, both the seller and the buyer are and must be in one space. And both entered it equally. Both have the same access to the goods. Therefore, the human relationships they establish are based on who they are as people. The architect tried to ensure that neither of them had an advantage.

As we leave the shop, we have the goods packed in wrappers that evoke in our memories the vision of the shop. Silver foil with red letters "Retti" and the brand logo. This is also the work of the architect. Silver is the color of the shop, the color of large surfaces made of anodized aluminum sheets. The shape of the brand logo is also the shape of the cutout of the portal. It is a symbol that has merged with the work.

What does it actually mean? Is it perhaps a big P, a letter that corresponds to our "R" in the Greek alphabet? Perhaps. For the inhabitants of Vienna, it now conveys the same meaning as the word Retti. In fact, it is the same sign as the signs of Chinese writing. It represents one word and as such can only be communicated through the subject. It is a convention. To anyone who does not know what it means, it does not convey anything specific. That it is a corporate brand becomes evident only from the context. Its choice had a purely subjective nature. However, it cannot be claimed that it does not captivate us in and of itself, by its shape. In fact, we can say even more: it is a sign formed by the composition of two symmetrically arranged, according to the vertical axis, symbolic elements that are also of a sign-like nature in themselves. And the outline of the whole is just as interesting and attention-grabbing as each of the two elements. This connection has resulted in a form that is definitely better capable of independent existence than its elements. It is more enclosed; its center of gravity lies at the center of the area defined by it, on the axis of symmetry, unlike the elements, which do not have an axis of symmetry, and their center of gravity lies not far from their perimeter.

Let us now investigate the elements of this sign! Why did Hollein choose them? Did he not use them in some other project of his? Yes, they can clearly be traced, for example, in the “city” project from 1962. Here they are part of the node of urban communications, Hollein's bold vision of future urbanism. They appear in a different configuration, but still in a symmetrical pair. One could expect that if we had more material on Hollein’s works, we would encounter them even more frequently. From the history of architecture, we know of several cases where a certain geometric element of a sign-like nature troubled significant creators throughout their lives. I mention, by chance, the sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt, Santini's star, and the labyrinth of Le Corbusier. Ultimately, one could point out the similarity of properties between graphical and verbal signs and recall that it almost always happens that some word pronounced completely by chance capturing us immediately with its sound aspect and compels us to constant repetition or stuns us with its absurdity.

It seems that in most of these cases, one can point out an interesting study by S. Freud "Memories of Childhood of Leonardo da Vinci" while searching for their genesis. Freud here employs it to explain the subconscious and shows its role in artistic creation.

* The new generation that enters the history of architecture at the end of the 1950s brings a reversal in the existing development. In 1964, when the already famous book by Sigfried Giedion was published for the first time in German (originally Space, Time, Architecture, Harvard University Press 1941, now: Raum, Zeit, Architektur, Otto Mainer Verlag, Ravensberg 1964), enriched with a new chapter "Jörn Utzon und die Dritte Generation," the new movement in modern architecture received its name: the “Third Generation” movement.

** The concept of urban space arises from the understanding that architecture is “the art of space” (as opposed to sculpture, which is “the art of matter”); space is its goal. But it is not only about interior space. Every architectural work helps define spaces externally, as they are (or should be) intentionally conceived by the architect to a greater or lesser extent, and we refer to these as urban spaces. We perceive these spaces as wholes and individual buildings that define or organize them; we essentially perceive them through these spaces. For we always perceive each individual object in relation to the urban space, and that is precisely what gives authentic perception an advantage over photography, which is unable to capture these relationships in their fullness.

*** The word portal here is used to denote that part of the shop that co-creates urban space, the exterior part here. The choice of this term was prompted by the fact that the shop does not actually have a display window; it is a smooth aluminum surface that frames the entrance to the shop.

Author: Petr Vaďura

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment