<wide-screen-cinema> in Uherské Hradiště</wide-screen-cinema>

The realization of the cinema in Uherské Hradiště is the result of extensive study work on dual-purpose buildings. The construction aimed to verify the principle on which this unique concept is based and the potential for broader application within the country.

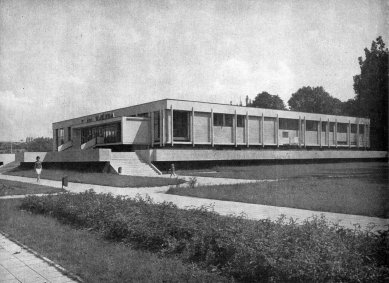

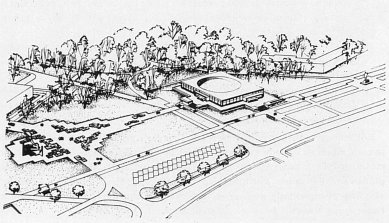

The building is designed as a widescreen 35 mm cinema for 550 viewers. It is located in a central, prominent position and, along with the adjacent museum, sports hall, and mature park, creates a cultural and recreational space in the city.

The operation of the cinema is designed unidirectionally, excluding the crossing of visitor movement, and includes, besides the cinema hall itself, a waiting hall, interspersed dressing rooms, sanitary facilities, a buffet, and an administrative part with a caretaker's apartment, an office, staff changing rooms, a doctor's office, and other auxiliary rooms.

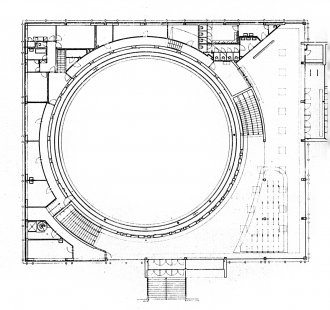

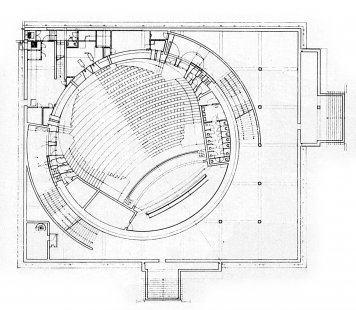

The acoustic shape of the amphitheater seating of the cinema is inscribed within a circumferential reinforced concrete cylinder, which is covered by a dome with a span of 27 m. The dome is mounted on a sloped circumferential ring, thus creating an acoustic profile for the ceiling. Technically, the construction of the dome was challenging, transmitting the prescribed loads to the pre-stressed base ring. For the dome formwork, site-cast reinforced concrete segments in the shape of wedges, 12 m long and 4 cm thick, were used. The building is equipped with dual climate control, sanitation, and electrical installations.

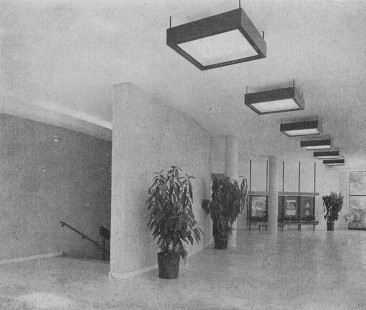

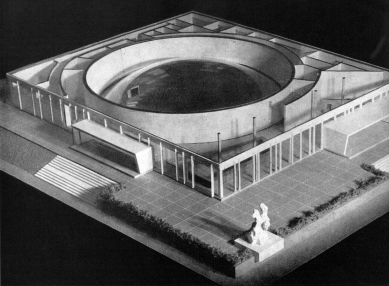

The entrance area is designed in a rectangular plan with glazed perimeter entrance walls, allowing a view of the exterior but also of the hall’s ceiling, which is covered in grass and planted. The entrance area is surrounded by terraces, part of which will be used as a summer café. Below the cinema's waiting hall, there is a dance wine cellar for 80 people, whose interiors are currently being completed. Along with the building, park arrangements for the adjacent space have been designed, which are now being adjusted for the Slovácko festivities in 1970.

Cinema Hvězda was ceremonially opened on Friday, October 6, 1967, with the screening of the film Marketa Lazarová by František Vláčil. The construction of the cinema took place from 1965 to 1968. The built-up space is approximately 10,000 m³.

Currently, the rough construction of a cinema in Prostějov is underway, which is designed on the same principle as the cinema in Uherské Hradiště.

In a significant number of our attempts at architecture, which I characterize as the confusion of the last decade, the new building of Cinema Hvězda in Uherské Hradiště stands out as an atypical phenomenon. Because it is not photogenic and does not limit itself to providing material for several more images in popular picture books about the new Czechoslovakia, it is unlikely to captivate even those readers who base their judgments solely on the superficial interest of the building. Its depth lies somewhere completely different. From the very beginning, it forces every visitor to acknowledge the incompleteness of any of their judgments. The persistent “but” appears immediately upon first encounter and is the hook of the matter, what prevents one from turning away and leaving with the blissful feeling of having so decisively ended a tour that seems a waste of time. That “but,” present at every step, ultimately surpasses all that seems easily dismissible at first glance and simultaneously evokes respect for the author and for that quality of his that could be called conscious freedom. Not the freedom caused by external circumstances or privileges, not the freedom of power and the violent manipulation of materials or structures, but the freedom of spirit that knows how to transcend the deficiencies of previous possibilities by surpassing them.

Cinema Hvězda stands on a small rise at the edge of the park, visible from the most vibrant urban intersection. Its regularity of square plan – dictatorial in its right angles and repetitive in detail – sharply contrasts with the carelessness of the old park and surrounding buildings. Only a corner of green grass between the intersection and the road has succumbed to the dictates of the new building and has been constrained by right-angled intersecting pathways. The building’s facades continue in a composed, almost classical pedantry throughout the entire exterior but do so with elegant rhythm, inventively utilizing what seems to be very limited possibilities of this principle. The alphabet of the building's shapes seems almost textbook familiar, with no exotic elements, no convoluted composition, yet it is felt that its elements are composed lightly and elegantly.

The presented staircase, emphasized entrance, and especially the fact that we approach the building along the axis, in the extended central crossbar of the building's square outline, reassure us of that classical impression. The building manifests itself in its outline, frontally. Our gaze penetrates through the glass facade into the foyer, coming to rest on the blue cylindrical wall that forms its backdrop. Automatically, we superimpose the axis along which we enter the interior as its axis of symmetry. The entrance to the building assures us that our calculations are incorrect. Several facts (entrances to the auditorium, outlining the foyer) show that the interior layout is symmetrically unusual: it follows the diagonal. And the resulting impression: surprise; and in a building externally so static, an unexpected feeling of spatial torsion is introduced into the foyer, bringing an element of intriguing tension. At first, it seems as if the inner cylindrical wall has been rotated into an originally unintended position under the influence of some mysterious twisting, along with the entire core of the layout. Thus, a whimsicality. But the realization that this rotation leads to a new, unexpected diagonal symmetry once again reassures us, albeit on a higher plane, of the complete intentionality of this act.

The blue cylindrical wall is pierced by a series of small windows. If we expected to find auxiliary spaces of the cinema hall or the hall itself behind them, we would be very mistaken. They lead to a peculiar, round atrium, shallow and spacious. However, it is not a normal atrium, flat, clear, with a water surface and pathways. Immediately from the base of the wall, the terrain rises and describes the surface of a spherical dome, which is almost as high as the outer walls of the atrium. Large stones, grass, and an approximately thick layer of clay. The hall is not here. It is a peculiar, absurd atrium; the viewer, who expected a hall based on experience, is surprised and again shaken in their seemingly confident judgment. The dome of the underground hall is, in relation to the exterior and its rectilinearity, undoubtedly an unexpected element.

Access to the actual hall is via two symmetrical staircases that follow the outline of the blue cylindrical wall. The hall itself is very wide, rather steeply descending from the amphitheater, set within a horseshoe-shaped outline (behind its outer walls, we feel additional spaces). The surface of the ceiling – a concrete vault – resembles anything but a simple spherical dome. Spatially, the hall is very pleasant and contrasts with its atypical shaping and the material deficiencies that again remind us of the sad state of our construction industry. Its location in the basement, undoubtedly requiring considerable earthworks, somewhat contradicts the assumption that this is merely the result of the arbitrary wish of an architect who hid a rather bulky concrete dome in the atrium just to avoid violating the austere prismatic eloquence of the building’s outer outline.

The construction still conceals something from us, something that can’t be revealed by mere exploration, something that still, as an unknown, influences its spatial formation.

Only the construction drawings speak a clearer language.

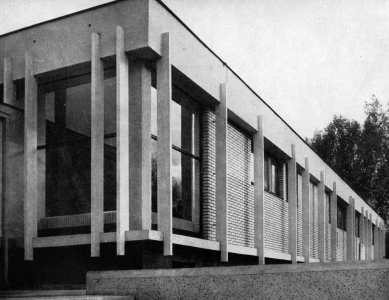

The core of the building is a massive cylinder of reinforced concrete that supports a reinforced concrete vault in the shape of a tilted spherical dome. This underground space is capable of withstanding dynamic effects (shocks) of the pressure wave and the high temperatures of the thermal wave from an atomic explosion. More than a meter layer of soil protects the dome. The tilt of the dome’s axis corresponds to the acoustic requirements of the interior space, as dictated by its peaceful use, as a cinema hall. During the concrete pouring of the dome, 12 shell segments in the shape of wedges were used as lost formwork, placed around the perimeter and on a temporary central column, and on them the reinforcement was laid, and the thick reinforced concrete dome was poured. The spaces between the horseshoe-shaped outer wall of the hall and the outer cylindrical wall are filled with sanitary and air conditioning equipment, which, when the armored doors to the hall are closed, forms its essential equipment. The floor in front of the doors to the hall rises slightly; it is removable and conceals the mechanism of the armored closure. The foyer and adjacent spaces on both floors are already exclusively single-purpose areas, serving the cinema and the newly established wine cellar; they have a lightweight reinforced concrete structure. The fillings made of white cement bricks, which create both "rear" facades, have an elegant effect, while both entrance facades are glazed.

Thus, a cinema and an atomic shelter or more aptly put, a cinema within an atomic shelter. This is what the construction of this building attests to. Yet even upon careful examination, an uninformed viewer cannot identify that second, unusual function of this building.

The author of the building developed 15 variants of using this shelter for social purposes during peacetime, but it is hard to imagine that any of them could match the suitability of the one realized.

If one understands that this is a cinema, but not just a cinema, one derives twice the pleasure from the bright foyer, which is penetrated by the surrounding park and city, yet which is also somewhat elevated above its surroundings, thus imparting clarity and graspability to everything outside. But even here, there is something more than just a mere contrast to the self-contained hall (the heaviness of the walls and its "shelterness" are hardly felt), it is also a confrontation with the free and vast space of the exterior, into which the eye can penetrate unobstructed through the two glazed walls and the atrium on the other side, appearing behind the small windows in the blue cylindrical wall. An atrium that is strange, contemplative, absurd, and above all, self-contained. It contains something of the strange mystery of the circle and is the exact opposite of that world outside and a premonition of that world below, the world of the hall and the shelter. Seemingly clear, from a distance simple and unisonous melody of the outer impression grows into a polyphonic counterpoint upon acquaintance with the interior spaces.

In this, the new cinema in Uherské Hradiště is an outstanding work. It erases the raw gloom of the concrete shelter without diminishing its seriousness and cautionary call. It humanizes the grim symbol of our time and serves this significant investment for entirely non-military purposes.

The building is designed as a widescreen 35 mm cinema for 550 viewers. It is located in a central, prominent position and, along with the adjacent museum, sports hall, and mature park, creates a cultural and recreational space in the city.

The operation of the cinema is designed unidirectionally, excluding the crossing of visitor movement, and includes, besides the cinema hall itself, a waiting hall, interspersed dressing rooms, sanitary facilities, a buffet, and an administrative part with a caretaker's apartment, an office, staff changing rooms, a doctor's office, and other auxiliary rooms.

The acoustic shape of the amphitheater seating of the cinema is inscribed within a circumferential reinforced concrete cylinder, which is covered by a dome with a span of 27 m. The dome is mounted on a sloped circumferential ring, thus creating an acoustic profile for the ceiling. Technically, the construction of the dome was challenging, transmitting the prescribed loads to the pre-stressed base ring. For the dome formwork, site-cast reinforced concrete segments in the shape of wedges, 12 m long and 4 cm thick, were used. The building is equipped with dual climate control, sanitation, and electrical installations.

The entrance area is designed in a rectangular plan with glazed perimeter entrance walls, allowing a view of the exterior but also of the hall’s ceiling, which is covered in grass and planted. The entrance area is surrounded by terraces, part of which will be used as a summer café. Below the cinema's waiting hall, there is a dance wine cellar for 80 people, whose interiors are currently being completed. Along with the building, park arrangements for the adjacent space have been designed, which are now being adjusted for the Slovácko festivities in 1970.

Cinema Hvězda was ceremonially opened on Friday, October 6, 1967, with the screening of the film Marketa Lazarová by František Vláčil. The construction of the cinema took place from 1965 to 1968. The built-up space is approximately 10,000 m³.

Currently, the rough construction of a cinema in Prostějov is underway, which is designed on the same principle as the cinema in Uherské Hradiště.

In a significant number of our attempts at architecture, which I characterize as the confusion of the last decade, the new building of Cinema Hvězda in Uherské Hradiště stands out as an atypical phenomenon. Because it is not photogenic and does not limit itself to providing material for several more images in popular picture books about the new Czechoslovakia, it is unlikely to captivate even those readers who base their judgments solely on the superficial interest of the building. Its depth lies somewhere completely different. From the very beginning, it forces every visitor to acknowledge the incompleteness of any of their judgments. The persistent “but” appears immediately upon first encounter and is the hook of the matter, what prevents one from turning away and leaving with the blissful feeling of having so decisively ended a tour that seems a waste of time. That “but,” present at every step, ultimately surpasses all that seems easily dismissible at first glance and simultaneously evokes respect for the author and for that quality of his that could be called conscious freedom. Not the freedom caused by external circumstances or privileges, not the freedom of power and the violent manipulation of materials or structures, but the freedom of spirit that knows how to transcend the deficiencies of previous possibilities by surpassing them.

Cinema Hvězda stands on a small rise at the edge of the park, visible from the most vibrant urban intersection. Its regularity of square plan – dictatorial in its right angles and repetitive in detail – sharply contrasts with the carelessness of the old park and surrounding buildings. Only a corner of green grass between the intersection and the road has succumbed to the dictates of the new building and has been constrained by right-angled intersecting pathways. The building’s facades continue in a composed, almost classical pedantry throughout the entire exterior but do so with elegant rhythm, inventively utilizing what seems to be very limited possibilities of this principle. The alphabet of the building's shapes seems almost textbook familiar, with no exotic elements, no convoluted composition, yet it is felt that its elements are composed lightly and elegantly.

The presented staircase, emphasized entrance, and especially the fact that we approach the building along the axis, in the extended central crossbar of the building's square outline, reassure us of that classical impression. The building manifests itself in its outline, frontally. Our gaze penetrates through the glass facade into the foyer, coming to rest on the blue cylindrical wall that forms its backdrop. Automatically, we superimpose the axis along which we enter the interior as its axis of symmetry. The entrance to the building assures us that our calculations are incorrect. Several facts (entrances to the auditorium, outlining the foyer) show that the interior layout is symmetrically unusual: it follows the diagonal. And the resulting impression: surprise; and in a building externally so static, an unexpected feeling of spatial torsion is introduced into the foyer, bringing an element of intriguing tension. At first, it seems as if the inner cylindrical wall has been rotated into an originally unintended position under the influence of some mysterious twisting, along with the entire core of the layout. Thus, a whimsicality. But the realization that this rotation leads to a new, unexpected diagonal symmetry once again reassures us, albeit on a higher plane, of the complete intentionality of this act.

The blue cylindrical wall is pierced by a series of small windows. If we expected to find auxiliary spaces of the cinema hall or the hall itself behind them, we would be very mistaken. They lead to a peculiar, round atrium, shallow and spacious. However, it is not a normal atrium, flat, clear, with a water surface and pathways. Immediately from the base of the wall, the terrain rises and describes the surface of a spherical dome, which is almost as high as the outer walls of the atrium. Large stones, grass, and an approximately thick layer of clay. The hall is not here. It is a peculiar, absurd atrium; the viewer, who expected a hall based on experience, is surprised and again shaken in their seemingly confident judgment. The dome of the underground hall is, in relation to the exterior and its rectilinearity, undoubtedly an unexpected element.

Access to the actual hall is via two symmetrical staircases that follow the outline of the blue cylindrical wall. The hall itself is very wide, rather steeply descending from the amphitheater, set within a horseshoe-shaped outline (behind its outer walls, we feel additional spaces). The surface of the ceiling – a concrete vault – resembles anything but a simple spherical dome. Spatially, the hall is very pleasant and contrasts with its atypical shaping and the material deficiencies that again remind us of the sad state of our construction industry. Its location in the basement, undoubtedly requiring considerable earthworks, somewhat contradicts the assumption that this is merely the result of the arbitrary wish of an architect who hid a rather bulky concrete dome in the atrium just to avoid violating the austere prismatic eloquence of the building’s outer outline.

The construction still conceals something from us, something that can’t be revealed by mere exploration, something that still, as an unknown, influences its spatial formation.

Only the construction drawings speak a clearer language.

The core of the building is a massive cylinder of reinforced concrete that supports a reinforced concrete vault in the shape of a tilted spherical dome. This underground space is capable of withstanding dynamic effects (shocks) of the pressure wave and the high temperatures of the thermal wave from an atomic explosion. More than a meter layer of soil protects the dome. The tilt of the dome’s axis corresponds to the acoustic requirements of the interior space, as dictated by its peaceful use, as a cinema hall. During the concrete pouring of the dome, 12 shell segments in the shape of wedges were used as lost formwork, placed around the perimeter and on a temporary central column, and on them the reinforcement was laid, and the thick reinforced concrete dome was poured. The spaces between the horseshoe-shaped outer wall of the hall and the outer cylindrical wall are filled with sanitary and air conditioning equipment, which, when the armored doors to the hall are closed, forms its essential equipment. The floor in front of the doors to the hall rises slightly; it is removable and conceals the mechanism of the armored closure. The foyer and adjacent spaces on both floors are already exclusively single-purpose areas, serving the cinema and the newly established wine cellar; they have a lightweight reinforced concrete structure. The fillings made of white cement bricks, which create both "rear" facades, have an elegant effect, while both entrance facades are glazed.

Thus, a cinema and an atomic shelter or more aptly put, a cinema within an atomic shelter. This is what the construction of this building attests to. Yet even upon careful examination, an uninformed viewer cannot identify that second, unusual function of this building.

The author of the building developed 15 variants of using this shelter for social purposes during peacetime, but it is hard to imagine that any of them could match the suitability of the one realized.

If one understands that this is a cinema, but not just a cinema, one derives twice the pleasure from the bright foyer, which is penetrated by the surrounding park and city, yet which is also somewhat elevated above its surroundings, thus imparting clarity and graspability to everything outside. But even here, there is something more than just a mere contrast to the self-contained hall (the heaviness of the walls and its "shelterness" are hardly felt), it is also a confrontation with the free and vast space of the exterior, into which the eye can penetrate unobstructed through the two glazed walls and the atrium on the other side, appearing behind the small windows in the blue cylindrical wall. An atrium that is strange, contemplative, absurd, and above all, self-contained. It contains something of the strange mystery of the circle and is the exact opposite of that world outside and a premonition of that world below, the world of the hall and the shelter. Seemingly clear, from a distance simple and unisonous melody of the outer impression grows into a polyphonic counterpoint upon acquaintance with the interior spaces.

In this, the new cinema in Uherské Hradiště is an outstanding work. It erases the raw gloom of the concrete shelter without diminishing its seriousness and cautionary call. It humanizes the grim symbol of our time and serves this significant investment for entirely non-military purposes.

Petr Vaďura

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment