Between technique and art lies the secret

interview with Daniel Libeskind

|

| photo: Tomasz Tom Kulbowski |

Daniel Libeskind: I never intended to become an architect. It was assumed that I would be a musician because I was somewhat of a child prodigy – I played the accordion so well that I was awarded a prestigious scholarship from the America-Israel Cultural Foundation (AICF). I still keep a review of my performance at the Tel Aviv concert hall, where I played with young Itzhak Perlman.

I have always loved drawing as well, and the limitations of the accordion became increasingly apparent. So I spent more and more time drawing. I became a fanatical admirer of the pencil. I traced a series of drawings of Hasidic weddings; I drew buildings, landscapes, and political cartoons. When we moved to New York, I enrolled in a technical drawing course at a Bronx high school and enjoyed it immensely. On the days I had class, I would wake up at five in the morning and couldn't wait for it. After school, I did my homework on the way home so that I could dedicate the rest of the day to honing my drawing skills. I drew obsessively late into the night until my fingers started to stiffen.

My drawing passion worried my mother. "You want to be a kumštýř? Do you want to end up hungry somewhere in an attic and not have enough money to buy a pencil? Is that the life you want?" she once asked directly. I argued that there are successful artists too! Like Andy Warhol. Warhol? For every Warhol, there are a thousand waiters without a dime. Become an architect. Architecture is a craft and also a form of art." And then she said something that would warm any architect's heart: "In architecture, you can always do art as well, but in art, you cannot do architecture. You kill two birds with one stone."

|

D. L.: The name was chosen for us by my grandfather Chaim. Chaim came from the poorest family of Orthodox Jews. He had to choose a surname in adulthood during the census when he was already living in Lodz with his wife and children. Until then, like most poor Jews from the countryside, he only carried his father's name, just like my father was known as Nachman ben Chaim – Nachman, son of Chaim. When my grandfather had to choose, he decided on the name Libeskind, which was his nickname – "dear child." When registering his name with the authorities, he intentionally dropped the letter e from the German word lieb so that his name would not be seen as German, but unmistakably Jewish – Libeskind.

Your grandfather chose nicely, in most photographs you smile sweetly, you write in your book that you are an optimist, yet you often have to fight hard for your projects. Your wife Nina is certainly a great support to you, having revived the nearly doomed project of the Jewish Museum in Berlin. She must be a very strong personality.

D. L.: My wife comes from a remarkable family, the Lewises. You don't mess with the Lewises. Her father David Lewis was a poor Russian Jew who landed in Canada around 1911 or 1912, received a scholarship to the Oxford Rhodes School, and returned to Canada, where he became one of its most progressive politicians. He founded and led the New Democratic Party (NDP) and was a parliamentary member until the 1970s. Nina's brother Stephen was the leader of the NDP in Ontario and was active in the province's legislature and later became Canada's ambassador to the United Nations. He now works in Africa as the Secretary-General's special envoy for the fight against HIV/AIDS. Her brother Michael and her sister – twin Janet are also politically active. Nina herself managed political campaigns; she simply has progressive politics in her blood.

|

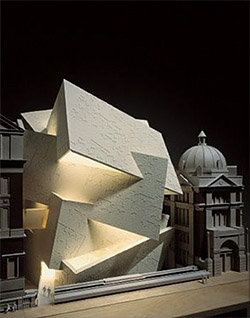

D. L.: I am not a deconstructivist; on the contrary, I believe in construction. When the Victorians built the museum 150 years ago, they did not decide on something that was in fashion 150 years before them, in the Georgian period. Victorians were brave and revolutionary, even shocking. They constructed a contemporary building. I designed the same. Just look at the outer walls of the building. You will find sculptures of visionaries and revolutionaries – Christopher Wren, John Barry, John Soane. Each had their eccentricities, but they were not stuck-in-the-mud traditionalists. If we keep looking back, we will condemn London to a nostalgic existence without perspective.

Your detractors, however, were not deterred.

D. L.: No, they asked me what the word harmony means to me. They wanted to know how my crystal tower, clad in special ceramics, would harmoniously connect with the charming yet shabby old museum. I replied that differences are harmonious. Mozart's harmonies differ from Bach's, which again differ from Copland's, and those are completely different from the harmonies of an infinite number of contemporary composers. And yet they can all appear together as parts of a single musical program, and often do.

Which architects would you like to have such a common "musical" program with?

D. L.: I really like Jean Nouvel; he is an elegant and intelligent man, an architect of high-tech in European terms. He became famous for his construction of the Arab World Institute, standing on the banks of the Seine in Paris. Its light-responsive façade looks like the irises of many eyes. I also admire Zaha Hadid. The last time I saw her, she had a shiny gold handbag in the shape of a butt, formed from some expensive material, almost unrecognizable from the real one. Zaha has her own bold style. For this woman originally from Iraq, living in a world that is still almost exclusively male, it is not always easy to be an architect. However, she has a rich imagination, stays true to her ideals, and is obsessed with her ideas – and it works, she is successful. It is surprising that a male perspective still prevails in architecture. But just like in many other areas, change is happening here too, and the result will be a transformation of architecture itself, as women will clothe it with their own experiences and bring new perspectives into it.

|

D. L.: You can be a melancholic musician and compose in minor keys. You can be a writer with a tragic view of the world or a filmmaker obsessed with the theme of despair. However, you cannot be an architect and also be a pessimist. Architecture, by its very nature, is an optimistic profession; at no point in your journey must you stop believing that two-dimensional drawings will result in real three-dimensional buildings. Even before millions of dollars and years of people’s lives are invested, you must know with absolute certainty that all that money and effort is worth it and that what will emerge will be a source of your pride and that it will outlive you. Ultimately, architecture is thus built on faith.

My architecture, which is often overtly expressive, makes some critics nervous, as many of them feel safer in an antiseptic world where emotions are kept in check and buildings are treated exclusively aesthetically.

Since the beginnings of modernism, buildings have been designed to show the world their neutral face, immune to expression. The goal is to create objective, not subjective architecture. But the truth is that no architecture, no matter how hard it tries to be neutral, can truly be neutral. Le Corbusier claimed that "a house is a machine for living in," but even if you live in a perfectly minimalist loft with white walls, it is still an expression of your personality, and thus no neutral space.

Thank you for the interview.

Alena Mizerová

translated by B. Kučerová and K. Tlachová

|

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment