|

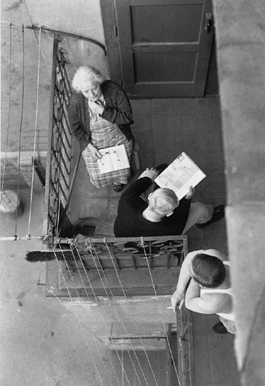

| Dolní Žižkov, photo Karel Cudlín |

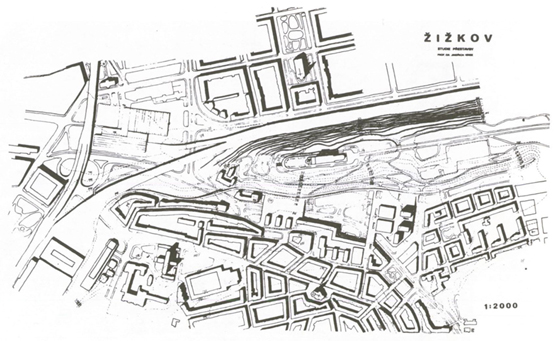

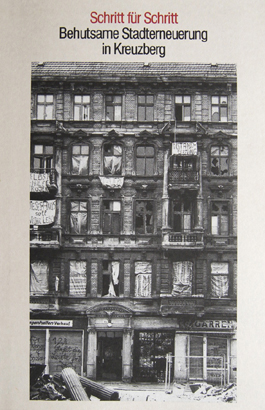

The premises, variants, and solutions to this controversial urban task are illustrated at the exhibition with models of the area, planning documentation, photographs, and texts. Archiweb has decided to bring the topic closer through an interview with architect Ivo Oberstein, which will be published alongside other texts in the spring in a publication that will further develop the topic of the exhibition. The editorial selection by Jiří Horský will include interviews with architects who participated in the Žižkov reconstruction, as well as an article by urbanist Jan Sedlák or sociologist Jiří Musil, along with interviews with "nameless" residents – whether forcibly deported or those who resisted the pressures of the time...

However, some of the texts can be found today on the pages of several "newspapers" in the pub U asanace, which is one of the spaces in the Gallery under the Town Hall (Municipality of Prague 3, Havlíčkovo náměstí 9), where the exhibition runs until January 28, 2010.