Hendrik P. Berlage: The Development of Modern Architectural Art in the Netherlands

Presented at the Society of Architects in Prague, on October 3, 1924

Source

Časopis Styl, ročník V. (X. 1924-25), str. 93-96

Časopis Styl, ročník V. (X. 1924-25), str. 93-96

Publisher

Tisková zpráva

15.08.2013 10:10

Tisková zpráva

15.08.2013 10:10

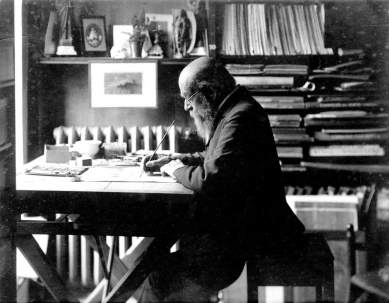

Hendrik Petrus Berlage

Whoever wants to understand the development of Dutch architecture in connection with the development of art in other countries must go back to the 1950s of the last century. A brief overview is sufficient.

In those years, it is possible to speak calmly about the decline of art as a social phenomenon, and even those who would want to judge it from an individualist perspective cannot deny that art is not the cause of the social world of thought, but that art is a result of the contemporary cultures.

This holds true for architecture especially. For in architectural art, in architectural monuments, artistic tendencies manifest themselves more faithfully than in written books; they manifest directly. This world of thought, this thought mood also manifests itself in furniture; the decorative arts belong to fine arts, and whenever we speak of fine art, we mean a broader concept, not just architecture.

The style of life and artistic style are expressions of the same ideology that first manifests itself in dual culture, in the unifying idea, which subsequently becomes characteristic of a society in a certain period.

If we look at the ideology of the 1950s, we observe the most powerful and noticeable democratization; the bourgeois, civic life gains supremacy over the aristocratic elements, which had been dominant until then. Hand in hand with this phenomenon, we can trace the beginnings of individualization. Therefore, we find that in those years, one could not yet speak of a fundamental style that would serve for aesthetic expressions, that all-pervading force that we have become accustomed to calling social ideology.

The transitional period of the 1950s led builders to seek, and they began the revival of Greek style, introducing Neo-Greek style—as it was called—which followed after the Empire style from the time of the French Empire and the time when the idea of imperial governance had strengthened so much after 1815. All attempts at reviving classicism failed; they were merely a reflection of a temporary and transitional fondness for Greek culture and Greek art.

What followed were remnants of all possible styles; only the one was missing that would be the style of its time. It was a complete cultural impossibility for that era to create a distinct style.

From this magical cauldron of architecture, two phenomena came to light. Firstly, there is the effort to adhere to national Renaissance and to adapt it to contemporary times.

Secondly, others sought salvation in medieval art, for it manifested the spirit of the Central European man in a distinctive and peculiar way. This developmental line was actually only a Renaissance interrupted, but not culminated. The Renaissance was a deviation, not a development.

This idea was nothing characteristically Dutch. Similar conclusions were drawn across Europe; only it can be said that in the Netherlands the ground was favorable for this understanding.

The Dutch national Renaissance was locally tinted; it took on certain solid features in the Netherlands. A major role was played by the building material, brick, which has been used in the Netherlands since ancient times. In the seventeenth century, it was combined with marble, resulting in a construction style that was appealing and became characteristic.

The medieval style essentially had constructive elements that are very close to the qualities that form the foundation of modern art. The development of medieval art went hand in hand with philosophical thinking: to work, to think, and to act rationally. This is the exact opposite of the Renaissance, which places greater emphasis on ornamentation, having a decorative character.

The development and penetration of new rationalistic methods was primarily contributed to by the development of industry, the development of machinery, which the constructing artist today relies on. The Renaissance of northern European countries differs from the southern European Renaissance because it developed with the help of medieval elements. The Middle Ages with guilds, trading houses, and societies contributed in a distinctive way to the development of architectural art. Additionally, the circumstance that French influences—France is after all the cradle of medieval art—backed by the influence of French political power, gained predominance and were willingly accepted, especially in the Netherlands (where French influence and political power operated fully until 1813). In addition to Empire influences, southern European construction traditions and the influence of southern European art also operated in the Netherlands. The gifted Viollet-le-Duc, this apostle of modern art, warned in vain, cried in vain; his voice remained the voice of a prophet crying in the wilderness.

It would be an unnatural phenomenon if the spirit of the time did not manifest itself in architectural art. How did modern art arise? Many are inclined to say it happened spontaneously. Once the spirit emerges, it develops rapidly; those who do not recognize that something can be the cause of new development do not explain anything. Those who oppose rationalism display reactionism.

One cannot construct without change according to old artistic forms. That would be unnatural.

Building a modern department store in the style of the temple of Athena Palladia would be sheer nonsense. It would be a construction delusion. Also, the use of modern materials has its special demands.

The mistake is revealed mainly in the inability to create something of its own, something new in the old footsteps. Copying is not art.

Such a mistake was actually committed already in the Renaissance, which anticipated wonders from the "rebirth" of ancient Roman art. Against the ancient Roman Colosseum, the Renaissance building actually represents a step back, not a step forward.

Only from Gothic can new art arise and develop. Construction is an eternal element. Constructing is an eternal element. The outer artistic form is a temporary, fleeting phenomenon.

This was not realized by the 1950s, nor was it realized by architecture. From misunderstanding arose mistakes, and from mistakes true art cannot be born. The Renaissance could only rely on ornament. The appreciation of beauty was neglected precisely because the essence of architectural art was forgotten.

In England at that time, for the first time, there was a rebellion against the understanding of art in the old way. This step was enthusiastically welcomed. The first attempts were merely latent, dormant art waiting for the magician who would bring it to life.

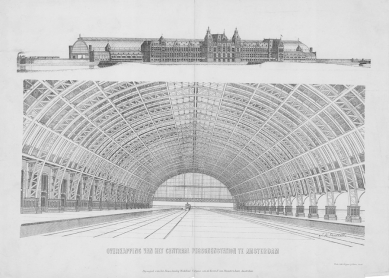

Such a person was in the Netherlands architect Cuypers, old Cuypers, who acknowledged the conclusions of Viollet-le-Duc and attempted to realize his ideas.

Cuypers began the fight against pseudo-Renaissance. The struggle was relatively easy since the Renaissance lacked a major builder in the Netherlands who would have defended it.

Cuypers easily triumphed and laid the foundations for a new Dutch architectural art. It was called rationalist art at its initial stages.

This art only developed with the development of other art. Although Gothic forms were applied with understanding and individuality, the constructions were still very complex, the artistic form was still overloaded, whereas the modern artistic ideal seeks simplicity. Therefore, Cuypers' art was still too eclectic. Only in England did they get a bit further, but in their great enthusiasm for guild work and their strong opposition to machine work, still preferring manual labor, they clung too much to medieval forms, even regarding ornamentation.

After literary propaganda, modern art first came to light in typographical processing; we can speak of book art, and only then did it lead to the execution of small subjects, then to furniture, and finally the new idea also revived architectural art. If we compare construction with other arts, we recognize that construction regularly lingers the longest on old traditions. This can be easily explained by the socially material character of the age.

The growth of architectural art in the Netherlands was hastened with particular fervor. Just as Erasmus of Rotterdam hastened the development of the old Renaissance with his writings, his book "In Praise of Folly," so too was new art elevated by literary propaganda. The only difference is that this time it was the artists themselves who conducted the propaganda; no scholars assisted them. Designers and typographers cared for new ornamental decoration in books, for new ornament in general, and soon small sculptures also appeared.

In the Netherlands, they understood that architectural art can only develop in a continuous stylistic development. Only under such conditions does painting and sculpture art develop as well, for it must be influenced by architectural ideas. But let us honestly say that we are still far from this ideal. For the apotheosis of individualism, the cause of spiritual fragmentation, the unsettling of the spirit is reflected, as is natural, in today's art.

It is remarkable how, to an increased extent, it is difficult to get Dutch spirits to cooperate at all. This is clearly spoken of by the extreme differences in architecture, which is still based on a unifying spirit. To foreigners, this fact must be very striking. Foreigners reached the conviction earlier that a unifying spirit is necessary in architecture. And this difference does not stand out in observing details, but from the overall first impression. Attention to individual details complicates and distorts the impression.

New ideas on applied art objects first manifested themselves. This was evidenced by the exhibition in Turin.

In terms of the form characteristic of modern ornament, it should be emphasized that geometric ornament prevails. From a stylistic perspective, it comes closest to architecture in general. For a draftsman can adorn buildings with such ornament, while he cannot with a naturalistic ornament. Also, if we consider this perspective, we come to the conviction that an impressionistic work cannot be applied in architecture as a decoration for walls. This notion of the unity of the stylistic concept has already penetrated in the Netherlands to such an extent that even an artistic work that has nothing to do with architecture takes on a linear character. This holds true for the works of many painters and sculptors. This is evidence not only of growth but also of misunderstanding, distorting the architectural idea.

At the same time, new shapes of furniture were proposed. The first attempts grew from the ground of a modern architectural organism, from architectural art. For furniture is essentially a work of construction. From all this, it must become clear how the architecture of the nineteenth century transgressed the principles of constructiveness and how new art is a reaction against its mistakes. Gothic pointed the way to modern art. As a result of all this, we must also understand modern decorative arts quite differently. The foundations for it were laid by Viollet-le-Duc: “que toute forme, qui n'est pas ordonnée par la structure, doit être repoussée“, every form that is not dictated by structure must be disregarded.

These basic assumptions require not only to maintain constructive relationships but also to pay attention to them in ornamental decoration.

With a rationalist understanding of the building as a whole goes hand in hand rational use and utilization of materials. Builders have already adapted to these demands. For technique is worthless if it dares to adopt unnatural forms and shapes.

The result of all these considerations led to the creation and manufacture of furniture with straight lines just like everything that new architectural art has newly discovered. For furniture that is bent in all directions, even if it is externally a piece of cabinet art, is in reality only an artistic perversion.

These ideas have guided Dutch art since 1890. This year can be considered as the starting point of new ideas.

In it, the difference between art in northern and southern European countries is already indicated.

Art in northern Europe adheres to constructive principles to a greater extent, it regards them actually a priori, to some extent even with passion. Southern European art adheres to constructive principles only secondarily, à posteriori; thus, it does not really regard them, since the old strong decorative tradition venerates artistic form above construction.

This international difference in artistic understanding manifests itself especially in Belgium. There lives a double people, and according to the barriers of nationality, one can trace the boundary of differences in northern European versus southern European art. The local modern art expresses itself in the endeavor for logical construction without forgetting artistic form. Thus, art in Belgium somewhat lacks expressive power, although otherwise it is held very high on the artistic point. Whereas modern architectural art expresses itself primarily through expressive power.

The Netherlands occupies a special place among other northern countries in Europe today. Perhaps this can be explained by the position it occupied during the historical Renaissance. Does not the ancient strong cultural and artistic character manifest itself at every new opportunity?

And this is always related to the fact that every renewal of an artistic form is actually only apparent, that it is merely a new transformation of what has existed eternally and consists of only a few elements.

Furniture thus gained new forms. After it came household ceramics. It naturally followed that here too it began with small items, a series of which ended with the rural house. This was the case in England, it was the case in the Netherlands, in accordance with a culture in which the house for one family is the basis of development in architectural art. Hence, the intimate civic nature of architectural art in both countries is explained, which eventually manifested itself in monumental public buildings.

The construction of modern Dutch houses develops gradually and quite in connection with furniture construction. Furniture is constructed according to simple logic under signs of clear attempts for beautiful effects and a harmonious impression of largeness. For architectural art is the art of mastering mass. Line has only a relative value. It is a matter of having the artistic form correspond; effect does not need to be considered. It sounds like a paradox, but does the construction not create its greatest impact under the moonlight, when all details disappear? And when the mass speaks solely?

Therefore, the space, which is the goal of architectural creation, must be kept in the simplest forms possible. The most essential manifestation of the new architectural art is that it has overcome the old ornament. And this is the new in today's architectural art. In this lies the strength of new architectural art.

The task of construction remains to be as modest as possible in its requirements. Any overloading with decorations is out of place. Excessive decorative quality signifies weakness in architecture. Some architects even exaggerate this. According to them, true modern architectural art begins where any ornamentation ceases.

To realize such architectural ornament is very easy in the Netherlands, because the construction material traditionally used in the Netherlands suits this very well. Brick ornamentation therefore adheres fully to the entirety of the building and its construction. Young Dutch architects have achieved real wonders here, and modern Dutch art can be considered typical construction with bricks, conducted with particular taste.

Since 1890, Dutch art has been developing ever higher, overcoming both individualistic and reactionary positions. It also defends itself against external influences, and defending against them is the most difficult task. It has been beneficial for Dutch architecture that an independent construction industry has developed in the Netherlands, which did not decline even in wartime.

After the rural house, after the farmhouse, which sometimes gained considerable dimensions, came the house in the city, so different from the rural in both dimensions and types. And after the civic house, public buildings followed. The great importance for the development of architecture is the effort to construct popular housing, garden cities, and finally large residential blocks in urban areas.

The "Woningswet" law was also beneficial for Dutch architecture, which allowed cities the authority to expropriate land according to approved urban plans and for appraisal prices. Cities were obliged to develop urban plans, thereby preventing speculation, the government provided the necessary capital under guaranteed interest rates, which are ensured by municipalities and associations that care for the construction of social housing. This benefited architectural art, and it experiences an apotheosis from the regulation that the development of plans for social housing was not left to entrepreneurs but to gifted architects.

Thus, constructing human residences was once again brought to the forefront of architectural culture, which leads to the construction of monumental buildings, monumental construction work, which is not and has never been the basis of architectural art, but its consequence.

We also begin to concern ourselves with the question of urban construction, and the happy consequence of this is that plans are assigned to architects who are not in the service of municipalities. This prevents these plans from being created only with regard to bureaucratic employment. The city thus becomes the final synthesis of art and an artistic work in the highest sense of the word.

In this way, a very fortunate foundation has been established in the Netherlands, from which architectural art grows, not only in large but also in small cities.

Everywhere new residences arise, new neighborhoods both working-class and middle-class, garden neighborhoods appear where you will find family houses and extensive blocks that significantly differ from previous designs. One cannot deny that this is a sign of a deeper understanding of beauty than was understood a few years ago when dry, not only sober reasoning dictated the tone of public architecture.

The capital has taken the lead in these endeavors. It has provided an example by allowing non-official builders and architects to develop urban plans. The buildings are then undertaken partly by the city, partly by building societies and cooperatives, as well as by private builders who designed them.

Two things have greatly contributed to elevating architectural taste. Firstly, so-called "schoonheidscommissie" (beauty commissions) have already been established in every larger city for years, artistic commissions, as we might loosely translate. The commission assesses the plans submitted and has an advisory voice regarding the appearance of the proposed projects. However, it cannot reject plans.

The second fortunate circumstance is that today's Netherlands has a number of young architects, talented architects, who feel called to dedicate themselves primarily to the construction of residential buildings. Thus, streets of an entirely new type are emerging, less restless than the old, where the individualism of architects was too strongly expressed.

It is becoming increasingly apparent that it is necessary to bring artistic guidance into construction, so that today’s age, characterized by excessive individualism to the point of hyper-individualism, can bring harmony into the endeavors of strong personalities, so that the image of the city takes on a certain unifying character starting from the project.

The beginnings of this have already been laid, but we will not reach the desired goal so soon. For there are artists who must be brought to a unifying perspective, though not to a mass perspective. The Amsterdam city council holds the view that a certain uniform perspective must be achieved, and that all such attempts and endeavors must be supported to this end. Many difficulties and resistance must still be overcome, which is understandable, for nothing is easier than creating a different, new artistic perspective, a new sense of art. This cannot be prescribed; it must be prepared in such a way that we find pleasure in it.

It can calmly be said that in our days, the Netherlands has a newly developing architectural art, and without the flavor of chauvinism, it can be stated that the Netherlands is one of the few countries where artistic architectural consequences have become a necessity, an indispensable necessity of artistic feeling.

Besides old materials, entirely new materials are utilized appropriately according to the new perspective.

Dutch experts themselves resist the thought that the Netherlands is the only country in Europe that has a national modern architecture today. This is asserted by some Dutch artists and art connoisseurs, and they are reinforced in this opinion by foreigners.

In the Netherlands, several currents have emerged in a relatively short time that have alternated in exerting influences on architectural art. These currents run parallel—concurrent with other artistic currents, as can be observed. From rationalism, they transition into cubism, futurism, and expressionism, not to mention dadaism.

This development cannot be compared with developments from previous eras because it differs in pace, and the environment in which this change occurs also differs.

This speaks of great tension in society; it speaks of great spiritual tension and effort, which no one can deny. The cause arising from today’s position in society and what emerges from it for culture is one and the same.

It can be inferred that the development of architectural art in general and the development of architectural art in the Netherlands will undergo several different phases before we reach a certain stabilization in which a new tradition could arise. What we currently observe in the Netherlands has a transitional nature; for now, we cannot speak of anything else, but it is certainly preparing the future of Dutch architectural art.

It has already been indicated that a certain stability, a certain establishment in art presupposes the stability of social views, and we are still far from that today. Certainly, one day we will reach this stability, and then a new temple will be built, which will be a synthesis arising from the general social idea. However, we primarily need a great deal of patience, patience, and again patience.

In those years, it is possible to speak calmly about the decline of art as a social phenomenon, and even those who would want to judge it from an individualist perspective cannot deny that art is not the cause of the social world of thought, but that art is a result of the contemporary cultures.

This holds true for architecture especially. For in architectural art, in architectural monuments, artistic tendencies manifest themselves more faithfully than in written books; they manifest directly. This world of thought, this thought mood also manifests itself in furniture; the decorative arts belong to fine arts, and whenever we speak of fine art, we mean a broader concept, not just architecture.

The style of life and artistic style are expressions of the same ideology that first manifests itself in dual culture, in the unifying idea, which subsequently becomes characteristic of a society in a certain period.

If we look at the ideology of the 1950s, we observe the most powerful and noticeable democratization; the bourgeois, civic life gains supremacy over the aristocratic elements, which had been dominant until then. Hand in hand with this phenomenon, we can trace the beginnings of individualization. Therefore, we find that in those years, one could not yet speak of a fundamental style that would serve for aesthetic expressions, that all-pervading force that we have become accustomed to calling social ideology.

The transitional period of the 1950s led builders to seek, and they began the revival of Greek style, introducing Neo-Greek style—as it was called—which followed after the Empire style from the time of the French Empire and the time when the idea of imperial governance had strengthened so much after 1815. All attempts at reviving classicism failed; they were merely a reflection of a temporary and transitional fondness for Greek culture and Greek art.

What followed were remnants of all possible styles; only the one was missing that would be the style of its time. It was a complete cultural impossibility for that era to create a distinct style.

From this magical cauldron of architecture, two phenomena came to light. Firstly, there is the effort to adhere to national Renaissance and to adapt it to contemporary times.

Secondly, others sought salvation in medieval art, for it manifested the spirit of the Central European man in a distinctive and peculiar way. This developmental line was actually only a Renaissance interrupted, but not culminated. The Renaissance was a deviation, not a development.

This idea was nothing characteristically Dutch. Similar conclusions were drawn across Europe; only it can be said that in the Netherlands the ground was favorable for this understanding.

The Dutch national Renaissance was locally tinted; it took on certain solid features in the Netherlands. A major role was played by the building material, brick, which has been used in the Netherlands since ancient times. In the seventeenth century, it was combined with marble, resulting in a construction style that was appealing and became characteristic.

The medieval style essentially had constructive elements that are very close to the qualities that form the foundation of modern art. The development of medieval art went hand in hand with philosophical thinking: to work, to think, and to act rationally. This is the exact opposite of the Renaissance, which places greater emphasis on ornamentation, having a decorative character.

The development and penetration of new rationalistic methods was primarily contributed to by the development of industry, the development of machinery, which the constructing artist today relies on. The Renaissance of northern European countries differs from the southern European Renaissance because it developed with the help of medieval elements. The Middle Ages with guilds, trading houses, and societies contributed in a distinctive way to the development of architectural art. Additionally, the circumstance that French influences—France is after all the cradle of medieval art—backed by the influence of French political power, gained predominance and were willingly accepted, especially in the Netherlands (where French influence and political power operated fully until 1813). In addition to Empire influences, southern European construction traditions and the influence of southern European art also operated in the Netherlands. The gifted Viollet-le-Duc, this apostle of modern art, warned in vain, cried in vain; his voice remained the voice of a prophet crying in the wilderness.

It would be an unnatural phenomenon if the spirit of the time did not manifest itself in architectural art. How did modern art arise? Many are inclined to say it happened spontaneously. Once the spirit emerges, it develops rapidly; those who do not recognize that something can be the cause of new development do not explain anything. Those who oppose rationalism display reactionism.

One cannot construct without change according to old artistic forms. That would be unnatural.

Building a modern department store in the style of the temple of Athena Palladia would be sheer nonsense. It would be a construction delusion. Also, the use of modern materials has its special demands.

The mistake is revealed mainly in the inability to create something of its own, something new in the old footsteps. Copying is not art.

Such a mistake was actually committed already in the Renaissance, which anticipated wonders from the "rebirth" of ancient Roman art. Against the ancient Roman Colosseum, the Renaissance building actually represents a step back, not a step forward.

Only from Gothic can new art arise and develop. Construction is an eternal element. Constructing is an eternal element. The outer artistic form is a temporary, fleeting phenomenon.

This was not realized by the 1950s, nor was it realized by architecture. From misunderstanding arose mistakes, and from mistakes true art cannot be born. The Renaissance could only rely on ornament. The appreciation of beauty was neglected precisely because the essence of architectural art was forgotten.

In England at that time, for the first time, there was a rebellion against the understanding of art in the old way. This step was enthusiastically welcomed. The first attempts were merely latent, dormant art waiting for the magician who would bring it to life.

Such a person was in the Netherlands architect Cuypers, old Cuypers, who acknowledged the conclusions of Viollet-le-Duc and attempted to realize his ideas.

Cuypers began the fight against pseudo-Renaissance. The struggle was relatively easy since the Renaissance lacked a major builder in the Netherlands who would have defended it.

Cuypers easily triumphed and laid the foundations for a new Dutch architectural art. It was called rationalist art at its initial stages.

This art only developed with the development of other art. Although Gothic forms were applied with understanding and individuality, the constructions were still very complex, the artistic form was still overloaded, whereas the modern artistic ideal seeks simplicity. Therefore, Cuypers' art was still too eclectic. Only in England did they get a bit further, but in their great enthusiasm for guild work and their strong opposition to machine work, still preferring manual labor, they clung too much to medieval forms, even regarding ornamentation.

After literary propaganda, modern art first came to light in typographical processing; we can speak of book art, and only then did it lead to the execution of small subjects, then to furniture, and finally the new idea also revived architectural art. If we compare construction with other arts, we recognize that construction regularly lingers the longest on old traditions. This can be easily explained by the socially material character of the age.

The growth of architectural art in the Netherlands was hastened with particular fervor. Just as Erasmus of Rotterdam hastened the development of the old Renaissance with his writings, his book "In Praise of Folly," so too was new art elevated by literary propaganda. The only difference is that this time it was the artists themselves who conducted the propaganda; no scholars assisted them. Designers and typographers cared for new ornamental decoration in books, for new ornament in general, and soon small sculptures also appeared.

In the Netherlands, they understood that architectural art can only develop in a continuous stylistic development. Only under such conditions does painting and sculpture art develop as well, for it must be influenced by architectural ideas. But let us honestly say that we are still far from this ideal. For the apotheosis of individualism, the cause of spiritual fragmentation, the unsettling of the spirit is reflected, as is natural, in today's art.

It is remarkable how, to an increased extent, it is difficult to get Dutch spirits to cooperate at all. This is clearly spoken of by the extreme differences in architecture, which is still based on a unifying spirit. To foreigners, this fact must be very striking. Foreigners reached the conviction earlier that a unifying spirit is necessary in architecture. And this difference does not stand out in observing details, but from the overall first impression. Attention to individual details complicates and distorts the impression.

New ideas on applied art objects first manifested themselves. This was evidenced by the exhibition in Turin.

In terms of the form characteristic of modern ornament, it should be emphasized that geometric ornament prevails. From a stylistic perspective, it comes closest to architecture in general. For a draftsman can adorn buildings with such ornament, while he cannot with a naturalistic ornament. Also, if we consider this perspective, we come to the conviction that an impressionistic work cannot be applied in architecture as a decoration for walls. This notion of the unity of the stylistic concept has already penetrated in the Netherlands to such an extent that even an artistic work that has nothing to do with architecture takes on a linear character. This holds true for the works of many painters and sculptors. This is evidence not only of growth but also of misunderstanding, distorting the architectural idea.

At the same time, new shapes of furniture were proposed. The first attempts grew from the ground of a modern architectural organism, from architectural art. For furniture is essentially a work of construction. From all this, it must become clear how the architecture of the nineteenth century transgressed the principles of constructiveness and how new art is a reaction against its mistakes. Gothic pointed the way to modern art. As a result of all this, we must also understand modern decorative arts quite differently. The foundations for it were laid by Viollet-le-Duc: “que toute forme, qui n'est pas ordonnée par la structure, doit être repoussée“, every form that is not dictated by structure must be disregarded.

These basic assumptions require not only to maintain constructive relationships but also to pay attention to them in ornamental decoration.

With a rationalist understanding of the building as a whole goes hand in hand rational use and utilization of materials. Builders have already adapted to these demands. For technique is worthless if it dares to adopt unnatural forms and shapes.

The result of all these considerations led to the creation and manufacture of furniture with straight lines just like everything that new architectural art has newly discovered. For furniture that is bent in all directions, even if it is externally a piece of cabinet art, is in reality only an artistic perversion.

These ideas have guided Dutch art since 1890. This year can be considered as the starting point of new ideas.

In it, the difference between art in northern and southern European countries is already indicated.

Art in northern Europe adheres to constructive principles to a greater extent, it regards them actually a priori, to some extent even with passion. Southern European art adheres to constructive principles only secondarily, à posteriori; thus, it does not really regard them, since the old strong decorative tradition venerates artistic form above construction.

This international difference in artistic understanding manifests itself especially in Belgium. There lives a double people, and according to the barriers of nationality, one can trace the boundary of differences in northern European versus southern European art. The local modern art expresses itself in the endeavor for logical construction without forgetting artistic form. Thus, art in Belgium somewhat lacks expressive power, although otherwise it is held very high on the artistic point. Whereas modern architectural art expresses itself primarily through expressive power.

The Netherlands occupies a special place among other northern countries in Europe today. Perhaps this can be explained by the position it occupied during the historical Renaissance. Does not the ancient strong cultural and artistic character manifest itself at every new opportunity?

And this is always related to the fact that every renewal of an artistic form is actually only apparent, that it is merely a new transformation of what has existed eternally and consists of only a few elements.

Furniture thus gained new forms. After it came household ceramics. It naturally followed that here too it began with small items, a series of which ended with the rural house. This was the case in England, it was the case in the Netherlands, in accordance with a culture in which the house for one family is the basis of development in architectural art. Hence, the intimate civic nature of architectural art in both countries is explained, which eventually manifested itself in monumental public buildings.

The construction of modern Dutch houses develops gradually and quite in connection with furniture construction. Furniture is constructed according to simple logic under signs of clear attempts for beautiful effects and a harmonious impression of largeness. For architectural art is the art of mastering mass. Line has only a relative value. It is a matter of having the artistic form correspond; effect does not need to be considered. It sounds like a paradox, but does the construction not create its greatest impact under the moonlight, when all details disappear? And when the mass speaks solely?

Therefore, the space, which is the goal of architectural creation, must be kept in the simplest forms possible. The most essential manifestation of the new architectural art is that it has overcome the old ornament. And this is the new in today's architectural art. In this lies the strength of new architectural art.

The task of construction remains to be as modest as possible in its requirements. Any overloading with decorations is out of place. Excessive decorative quality signifies weakness in architecture. Some architects even exaggerate this. According to them, true modern architectural art begins where any ornamentation ceases.

To realize such architectural ornament is very easy in the Netherlands, because the construction material traditionally used in the Netherlands suits this very well. Brick ornamentation therefore adheres fully to the entirety of the building and its construction. Young Dutch architects have achieved real wonders here, and modern Dutch art can be considered typical construction with bricks, conducted with particular taste.

Since 1890, Dutch art has been developing ever higher, overcoming both individualistic and reactionary positions. It also defends itself against external influences, and defending against them is the most difficult task. It has been beneficial for Dutch architecture that an independent construction industry has developed in the Netherlands, which did not decline even in wartime.

After the rural house, after the farmhouse, which sometimes gained considerable dimensions, came the house in the city, so different from the rural in both dimensions and types. And after the civic house, public buildings followed. The great importance for the development of architecture is the effort to construct popular housing, garden cities, and finally large residential blocks in urban areas.

The "Woningswet" law was also beneficial for Dutch architecture, which allowed cities the authority to expropriate land according to approved urban plans and for appraisal prices. Cities were obliged to develop urban plans, thereby preventing speculation, the government provided the necessary capital under guaranteed interest rates, which are ensured by municipalities and associations that care for the construction of social housing. This benefited architectural art, and it experiences an apotheosis from the regulation that the development of plans for social housing was not left to entrepreneurs but to gifted architects.

Thus, constructing human residences was once again brought to the forefront of architectural culture, which leads to the construction of monumental buildings, monumental construction work, which is not and has never been the basis of architectural art, but its consequence.

We also begin to concern ourselves with the question of urban construction, and the happy consequence of this is that plans are assigned to architects who are not in the service of municipalities. This prevents these plans from being created only with regard to bureaucratic employment. The city thus becomes the final synthesis of art and an artistic work in the highest sense of the word.

In this way, a very fortunate foundation has been established in the Netherlands, from which architectural art grows, not only in large but also in small cities.

Everywhere new residences arise, new neighborhoods both working-class and middle-class, garden neighborhoods appear where you will find family houses and extensive blocks that significantly differ from previous designs. One cannot deny that this is a sign of a deeper understanding of beauty than was understood a few years ago when dry, not only sober reasoning dictated the tone of public architecture.

The capital has taken the lead in these endeavors. It has provided an example by allowing non-official builders and architects to develop urban plans. The buildings are then undertaken partly by the city, partly by building societies and cooperatives, as well as by private builders who designed them.

Two things have greatly contributed to elevating architectural taste. Firstly, so-called "schoonheidscommissie" (beauty commissions) have already been established in every larger city for years, artistic commissions, as we might loosely translate. The commission assesses the plans submitted and has an advisory voice regarding the appearance of the proposed projects. However, it cannot reject plans.

The second fortunate circumstance is that today's Netherlands has a number of young architects, talented architects, who feel called to dedicate themselves primarily to the construction of residential buildings. Thus, streets of an entirely new type are emerging, less restless than the old, where the individualism of architects was too strongly expressed.

It is becoming increasingly apparent that it is necessary to bring artistic guidance into construction, so that today’s age, characterized by excessive individualism to the point of hyper-individualism, can bring harmony into the endeavors of strong personalities, so that the image of the city takes on a certain unifying character starting from the project.

The beginnings of this have already been laid, but we will not reach the desired goal so soon. For there are artists who must be brought to a unifying perspective, though not to a mass perspective. The Amsterdam city council holds the view that a certain uniform perspective must be achieved, and that all such attempts and endeavors must be supported to this end. Many difficulties and resistance must still be overcome, which is understandable, for nothing is easier than creating a different, new artistic perspective, a new sense of art. This cannot be prescribed; it must be prepared in such a way that we find pleasure in it.

It can calmly be said that in our days, the Netherlands has a newly developing architectural art, and without the flavor of chauvinism, it can be stated that the Netherlands is one of the few countries where artistic architectural consequences have become a necessity, an indispensable necessity of artistic feeling.

Besides old materials, entirely new materials are utilized appropriately according to the new perspective.

Dutch experts themselves resist the thought that the Netherlands is the only country in Europe that has a national modern architecture today. This is asserted by some Dutch artists and art connoisseurs, and they are reinforced in this opinion by foreigners.

In the Netherlands, several currents have emerged in a relatively short time that have alternated in exerting influences on architectural art. These currents run parallel—concurrent with other artistic currents, as can be observed. From rationalism, they transition into cubism, futurism, and expressionism, not to mention dadaism.

This development cannot be compared with developments from previous eras because it differs in pace, and the environment in which this change occurs also differs.

This speaks of great tension in society; it speaks of great spiritual tension and effort, which no one can deny. The cause arising from today’s position in society and what emerges from it for culture is one and the same.

It can be inferred that the development of architectural art in general and the development of architectural art in the Netherlands will undergo several different phases before we reach a certain stabilization in which a new tradition could arise. What we currently observe in the Netherlands has a transitional nature; for now, we cannot speak of anything else, but it is certainly preparing the future of Dutch architectural art.

It has already been indicated that a certain stability, a certain establishment in art presupposes the stability of social views, and we are still far from that today. Certainly, one day we will reach this stability, and then a new temple will be built, which will be a synthesis arising from the general social idea. However, we primarily need a great deal of patience, patience, and again patience.

Translated by R. Vonka

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.