Crematoria in Interwar Czechoslovakia

|

History and Development of the Architectural Type

Pardubice - An Attempt at the First Czech Crematorium

Crematoria in Ostrava, Nymburk, Most, and Plzeň

Brno - An Attempt at a New Architectural Type

Disputes Over the Prague Crematorium

Arnošt Wiesner – On the Construction of a Crematorium (1928)

History and Ideological Content of the Architectural Type of Crematorium

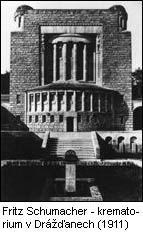

The driving force behind the cremation movement, which became an important element of organized associations of cremation advocates and their international cooperation, must be sought in the European national movement of the years 1850-70. The wave of romanticism also influenced the first types of crematoria; for example, in Italy after the unification of the country, they often mimicked the model of the ancient temple, while in Great Britain they were built in the neo-Gothic sacred style. For the first time, German authorities began to intervene in the development of these buildings, requiring builders and architects to ensure that the new architectural type did not conform to sacred architecture. As a result, several successful projects emerged in Germany, such as the crematorium in Dresden (1911) by Fritz Schumacher.

|

Architectural Development of the Crematorium

The concept of the internal architectural space of crematoria evolved from three types: the ancient temple, the single-nave basilica, and the central sacred structure. The first built crematorium in Milan copied the enclosed inner space of the ancient temple. The core of the building was not the ceremonial hall but the cremation chamber, with a waiting room on the right side and a mortuary chamber on the left. The ceremonial hall was replaced by an open columned space reminiscent of the peristyle of ancient temples. The spatial arrangement of the crematorium in Milan was soon criticized, as the bereaved almost became witnesses to the cremation. In the future, builders sought to ensure that in order to maintain dignity, each crematorium contained a ceremonial hall, bringing this type of construction closer to a Christian temple or chapel. The central inner space of the building became the ceremonial hall with an elevated choir platform above the entrance or over the catafalque. Initially, around the hall were grouped only the waiting room and a priest's room; later, additional rooms were added (office, urn distribution, etc.). The catafalque placed against the entrance to the ceremonial hall served to display the coffin, which after the ceremony would move into the back rooms—here, the furnace and other technical rooms were located. The cremation chamber was designed either at the level of the ceremonial hall or underground. The first furnaces resembled gas retorts but had an opening for air access. The later type—the refractory generator heating, invented by engineer B. Siemens in 1878—was the most widespread, with engineer R. Schneider's furnace from 1892 becoming a refinement of this type. Coking heating was later replaced in the 1930s by illuminating gas according to a patent from the American company Surface Combustion Co.

Efforts to Build a Czech Crematorium in the Territory of Austria-Hungary

The rigorous Habsburg monarchy, relying on the Catholic Church, was not inclined towards the construction of crematoria, yet did not prevent citizens from having deceased bodies cremated in crematoria outside its territory. On the ground of Austria-Hungary, the society Die Flamme was established in 1885, which then spurred the formation of a society in Bohemia. An exceptional figure in the history of the Czech cremation movement was Vojtěch Náprstek—he became a member of the city council of Prague in 1881 and, among other things, advocated for the legalization of optional cremation. In 1883 and again in 1888, he proposed building a crematorium in Prague. The society that would specifically address this matter was founded by another figure—Prague city hygienist MUDr. Jindřich Záhoř. The activity of the Society for the Cremation of Corpses primarily revolved around promoting cremation through lectures and publishing, thus preparing the ground for a new organization that began to focus on the practical side of the issue.

|

After the XIV. World Congress of Free Thought held in Prague in 1907, a separate section of this association, the Crematorium - Society for the Cremation of the Dead, was established in 1909. The close connection with the anarchistically oriented Free Thought leaves no doubt that in the beginning it was not just about promoting the ideas of modern cremation. Evidence of this can be the very personality of the theater director Jaroslav Kvapil, then the chairman of the society (a member of the anti-Habsburg resistance, a mobster, the grandmaster of the Jan Ámos Komenský lodge, etc.). After the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic, Kvapil became a member of the Constituent Assembly, where he advocated for the legalization of cremation (the so-called "LEX KVAPIL" approved in 1919).

The period before World War I includes an ideational competition for a new cemetery proposal in Prague from 1912, which also considered the construction of a crematorium. (5) The first prize in the competition was awarded to Richard Knight Klenka from Vlastimil. Among the most advanced projects were those of modernists Jaroslav Rössler, Antonín Engle, and Otakar Novotný. However, this otherwise generous plan again fell through. From 1912 also comes Hofman's project for Ďáblice, which likely included an expressionistically designed crematorium. However, due to a lack of funds, only the wall and the side gate (1912-14) from the entire project were implemented.

In 1919, Ing. František Mencl (1879-1960) became the second chairman of the society, a building adviser to the capital city of Prague and an expert in bridge construction. His path to the society also led through Free Thought. His presence brought into the cremation movement a renowned construction specialist who oversaw almost every competition and project. He wrote professional articles and papers on the architecture of crematoria, and in 1919 published the document European Crematoria, where he published all available information about this building type. He came up with a plan for the systematic construction of Czech crematoria based on loans to communities at lower interest. He took care of organizing public exhibitions and lectured throughout the republic, also being one of the initiators of the international organization, which was established under the name International Cremation Federation in London.

Liberec - The First Crematorium in Czechoslovakia

|

The Liberec crematorium, located on an elevated plateau above the city, embodies primarily the romantic imperial German ideals in its architecture. The romantic idea, capturing the character of the building, already appears in the location and the name of the project Feuerburg. The Fire Castle, which drew inspiration from the victorious eagle, was to rise on Mount Monstransberg like an indomitable fortress. The entire concept of the crematorium was conceived by the architect in a solemn and symbolic manner. The building still captivates with its massive entrance featuring two monumentally Egyptian columns and abstracted figures of guardians on both sides, reminiscent of drawings of the guardians of a fantastic castle from Kotěra's illustration for The Tale of the Black Knight (1902). Bitzan's guardians of the temple are more like tombstones than sculptures. Half of their bodies are concealed by shields with animalistic symbols in a circle: owl, snake, lion, eagle. The guardians’ wings are stylized into the shape of birds—eagles—the symbol of the German Empire, the attribute of strength and victory. The same elements can be found on the architecturally much more interesting Dresden crematorium by Fritz Schumacher.

1) Helmut Weihsmann, Das Rote Wien: Sozialdemokratische Architektur und Kommunalpolitik, 1919-1934, Vienna 1985, p. 243.

2) Markéta Svobodová, Architectural Development of Sacred Buildings of the Czechoslovak Hussite Church in the 20s - 40s of the 20th Century, in: SYNESIS. Proceedings of the Mikulov Center for European Culture, vol. 2., Brno 2006.

3) Jan Nekvasil, Prague Crematoria and Cremation in General, Prague 1946.

4) The crematorium project of the Society for the Cremation of Corpses in: AA NTM estate of Pavel Janák, fund 85, no. 2/6.

5) Critique of the whole competition in: Otakar Novotný, Style IV, 1912, p. 283.

6) F. Rüchter, Fire Hall - Urn Grove in Reichenberg, Reichenberg 1928. - Project and plans of the crematorium archived in: SOA Liberec, sign. K/2.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

3 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Krematorium Karlovy Vary

M.Rund

18.01.07 10:14

Díky

Jan Kratochvíl

18.01.07 11:53

Link na přidaný článek o kreamatoriu K.Vary

M.Rund

24.01.07 12:54

show all comments