Archdiocesan Museum Olomouc

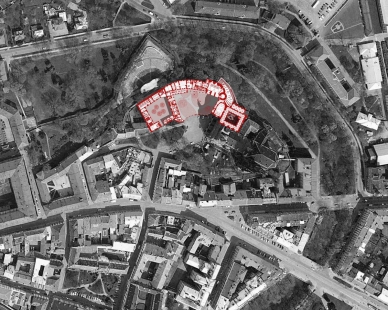

The Olomouc Castle, within which the Archdiocesan Museum was ceremoniously opened this June, was until recently present only in the past of the city, and thus more for historians than its residents. Therefore, it is often accompanied by the epithet former, both in the name of the national cultural monument - former Přemysl Castle - and in other naming variations. The slumber of the buildings and the Václav Square itself, where the museum is located, was disturbed only by occasional church festivities and limited tourist traffic around St. Wenceslas Church and the neighboring remnants of the Romanesque palace, Gothic cloister, and the reconstructed chapel of St. John the Baptist. (1) Despite this, the castle could leave an imprint on everyone's memory as an anomaly in the middle of a big city. Together with historian Jan Bistřický, we walked through the Heraldic Hall in the building of the former capitular deanery several times as part of the seminar Introduction to Auxiliary Historical Sciences, and with archaeologist Vít Dohnal, I dug for several summer weeks in the former carriage house, roughly where the reinforced concrete structure with a ramp is located today. In our spare moments, we curiously wandered through shabby corridors and peered into the mysterious rooms of this building - the palace that is used by Palacký University. It was a house turned toward memories, of which there were many in Olomouc shortly after the departure of Soviet troops. Only evening drawings of acts lent the building a certain piquancy, but the melancholic mood of the small-town Václav Square indulgently muted any extravagance, so even the students moved about in the spaces clouded by an undefined past somewhat more quietly than elsewhere.

Perhaps for these reasons, until recently, any mention of the Olomouc Castle was dismissed within an esoteric circle of people; after all, what did this castle represent in the eyes of the public? What did the remnant of the Romanesque palace with the Gothic cloister and half Gothic and half modern - historicizing chapel, or the baroque, antiquated buildings of the deanery, with their past glorious history, mean for the city? For visitors and many residents alike, it was a non-existent island, situated outside of this world.

The Archdiocesan Museum is an example of what can be achieved, in a good case, through a change of owner and intervention by a higher power in the form of a visit from John Paul II, when serious consideration finally began for such an institution. The nationalized buildings were returned to the Roman Catholic Church, with the local archbishopric still managing large collections of ecclesiastical art to this day. Additionally, there was an example of earlier museum usage of part of the deanery in the 1930s. Moreover, there was an initiative institution in the form of the local Museum of Art, which won a tender in 1997 to become the founding institution of the aforementioned museum.

The solution of how to turn the various buildings into a museum institution was not left to chance and local conditions, which was certainly a good thing. In 1998, an architectural competition was announced, and a group of architects was invited who clearly understood this matter as an artistic question of coexisting contemporary architecture and new designation with the historical site (Aleš Burian and Gustav Křivinka, Mikuláš Hulec, Vít Máslo, Josef Pleskot, Viktor Rudiš, Jan Šépka). Additionally, the submitted designs were evaluated by a representative commission (Chair Miroslav Masák, members Jiří Bureš, Tomáš Černoušek, Ladislav Daniel, Zdeněk Lukeš, Michal Sborwitz, Josef Štulc, Rostislav Švácha, Pavel Zatloukal), which is not common in our country to this day. Surprisingly, in Olomouc, this was the second major architectural competition that was ultimately taken to implementation, largely thanks to the director of the Museum of Art, Pavel Zatloukal, and other museum employees. (2)

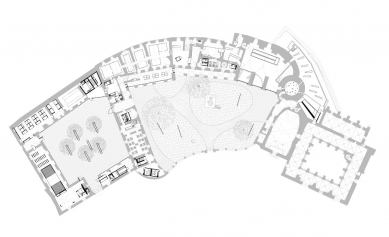

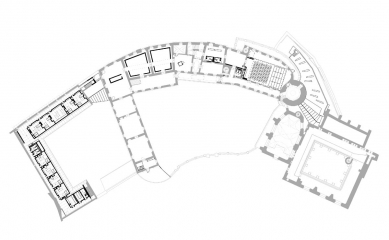

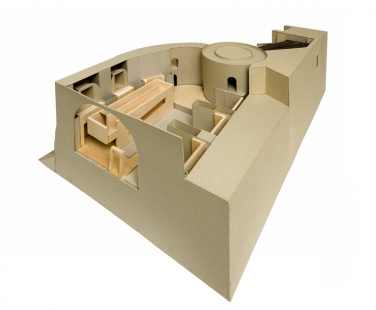

Noteworthy among the fifteen evaluated designs is the project by the AP studio of Josef Pleskot, awarded third prize, notable for its provocative entrance into the space of Václav Square, extending into the courtyard of the deanery and primarily into the economic yard, where the main exhibition hall of the museum was placed. The proposal was rejected partly because it radically addressed more than was required and beyond the capabilities of the client. On the other hand, it pointed out the limits of possibilities to approach the castle as an urban whole. The first prize was awarded to the team of Viktor and Martin Rudiš, proposing a passage between the deanery and the remnants of Zdik's Palace through a breakthrough in the Romanesque round tower, an intervention understood as unacceptable. The second prize went to the Brno team of Aleš Burian and Gustav Křivinka, inserting into the space of the curtain wall between the fortress and the deanery a passage in the form of an exhibition pavilion, rising above the existing wall with a band window along its entire length and dealing with the varying heights of the terrain using built-in stairs. The best result was ultimately awarded to the proposal by authors Petr Hájek, Tomáš Hradečný, and Jan Šépka (studio HŠH), who incorporated connecting ramps into the buildings and similarly inserted a connecting exhibition hall into the courtyard, yet with an exit to the Gothic cloister that does not exceed the medieval wall. From the beginning, it was pointed out that their approach draws lessons from the work of their teacher Emil Přikryl, especially from his Benedict Rejt Gallery in Lounech.

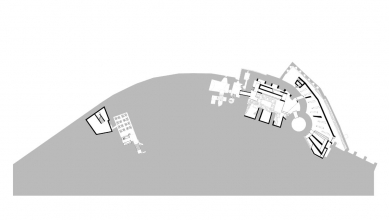

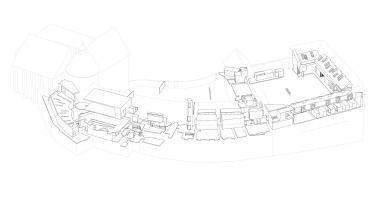

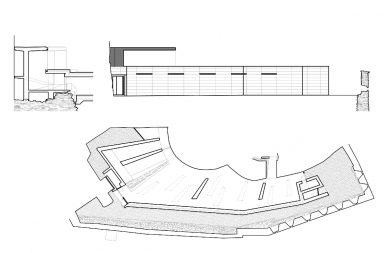

The authors wrote in the proposal justification about the "unrepeatability of the amalgamation of shapes ... developing around the organic line of the walls." They considered the circular tower with the chapel of St. Barbara as the focal point of the whole solution, reflected in the branching of slits arranged to naturally illuminate the exhibition spaces of the New Hall from above. Both outside and inside the historical buildings, they adhered to the idea of minimal interventions into the heritage substance of the objects, which, in an atmosphere inclined to a conservative approach to this monument, was positively received. Meanwhile, they considered the monuments as a repository of a structure composed of clearly differentiated new elements inserted into the historical constructions and spaces, materially based on the modernist trio: concrete, glass, metal. The commission then stated that: "The proposal is visually architecturally clean and stylistically defined in forms and materials… Sensitivity to the protection of the material substance of the monument is extraordinary and is expressed in the overall tone of the proposal." (3)

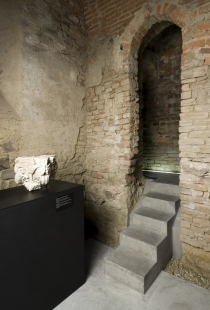

The first phase of the museum construction was completed in the summer of 2003 with the opening of its operational facilities, located in the buildings around the former economic yard of the deanery. For the professional public, this was an opportunity to see how the authors applied the idea of intervention into the historical environment through novelties, differentiated both materially and aesthetically, as indicated in the above-mentioned insertion of new architectural elements and complete spatial forms into historical constructions and spaces. The idea took on its final form of materially compact embedded boxes and containers. A showcase example is the expression "concrete" offices in the attic of the northern wing. Thus, the historical buildings retain a certain autonomy as spatial entities, where: "In the old shell, new steel and concrete organisms are scattered that may increase, decrease, or be replaced by another inner tissue for new life." (4)

Nothing changed this even with adjustments made to the original project based on construction-historical and archaeological research. Outwardly, these changes were most pronounced in the case of the connecting exhibition hall, called the New Hall. The original design had planned for the entire space of the courtyard to be filled from the walls of the capitular deanery to the fortress wall; however, in the end, the structure leaves a narrow passage between the wall and the inserted new form, highlighting both the medieval fortification and the insertion in the form of the concrete body with a terrace.

A similar approach was tested by studio HŠH in Olomouc during the reconstruction of Upper Square and its paving, where they preserved the diverse structure of historical origins, which they simply repaired and into which they introduced new elements in the form of furnishings or partial interventions (metal plates, city model). During this project, they experienced the provinciality of Olomouc when they encountered criticism from both parts of the public and from some politicians and representatives of heritage protection. They did not hesitate to express a certain skepticism about the acceptance their realization received: "The square is done; the cries are slowly fading - the city begins to reconcile with its square, repairing the fountains and columns, and starts to return to its slow Hanak tempo." This means, among other things, "killing space," based on an incapacity to use the public emptiness of the city and the living room with a repaired, past-imprinted carpet, as they pondered over the Upper Square issue in studio HŠH. (5)

In the case of the Archdiocesan Museum, as indicated by Petr Rezek and Rostislav Švácha in the texts on the occasion of the opening of the first phase, they seem to have successfully identified the basic framework for the overall intervention into historical objects. While Rezek thinks of the installation in connection with Scarpa as a reinterpretation of a work of art in a predominantly historical gallery and museum space, Švácha emphasizes the concept of the architectural line in Scarpa, meaning a unifying and simultaneously fundamental idea of the project that determines what and how should be done, altered, removed, or preserved to avoid deforming the architectural work directed at revitalizing the monument. (6)

As we walk through the rooms of the recently opened Olomouc museum, we can clearly recognize the aforementioned aspirations. The axis became the connection of the former capitular deanery with the remnants of Zdik's Palace, inserted with the New Hall in the courtyard, accessible via concrete ramps. This concrete insertion defines the shape of part of the basement, connected to the neighboring Gothic cellar. Even on the ground floor, some areas of the exhibition are dedicated to the presentation of the development of the building (the carriage house). The first floor is more modest from this perspective, which results from a greater degree of preservation of historical elements. Present custodians will properly instruct the visitor in this regard to wear the well-known "castle" slippers as they will traverse historical, albeit chronologically recent, interiors (the Heraldic Hall from the 19th century).

In terms of materials, it is the concrete walls, floors, and ceilings in the basement and ground floor that clearly delineate the present, which seems to levitate above or in the neighborhood of older constructions. Even the connecting concrete tunnel to the old cellar rooms feels naturally integrated, as though it had always been there. These vectors assist the visitor in independently navigating the tour. In the second phase, the principle of boxes or containers, organisms of the present, was similarly applied, if we adhere to the architects’ argument. This is evident in the service facilities - restrooms and cloakrooms. These are made of stainless steel, a relatively exclusive but unforgiving material. Unforgiving enough that I do not envy the staff the maintenance or service of these gems. It is basically "offensive" architecture, or architecture against "architecture," against functionality-oriented architecture, possibly in the authors' view of a primitive servility that could lead to an anonymous museum environment, thereby assigning a certain degree of anonymity to the exhibited works of art. It is precisely the interaction between the exclusivity of architecture and the exclusivity of works of art that offers a certain orientation in the value hierarchy of the applied architecture. Perhaps Pavel Zatloukal’s reaction to the resulting form of contemporary architectural intervention in the Archdiocesan Museum, as an architecture of "Narcissus with closed eyes" (Architect No. 9 / 2006), stems from the tension that arises between intentions, real possibilities, and acceptance of the final work.

But are not these shortcomings (or others of which I am unaware) among those elements of organisms, of which some will surely perish while other parts flourish? The same applies to the acute-angled and robust handles, glass railings, metal grips, "concrete" shelves, or scarcely openable skylights of the museum offices. Is everything wrong, or will users learn to coexist with it just as we will learn to coexist with that "architecture" whose only ambition is to serve? Or is this extravagance meant for fellow architects, the public, and the media? After all, that would not be worth the time, I tell myself. Instead, let us consider the museum of artworks in the context of their staging and the architecture subordinate to it. What kind of scene did the architects create here for works of art and what for visitors? Is the chosen approach effective?

The exhibited works of art did not arise for such a mode of presentation; they celebrated faith in God. They were often placed in different conditions that are, today, gone. Something of the monumentality is carried within the spaces treated in exposed concrete, formed of glass or black-painted sheets. The robustness of the elements and the material of the boxes indicates that we encounter something unusual here. Even the parade of Madonnas in the New Hall, made of concrete and lit from above by glass slits, feels so unreal, as if it were the dream of an art lover in delirium. The fragility of the sculptures of the High Middle Ages is reflected in the form of a filigree concrete shell.

To the superhuman dimension or ascetic position of the non-human aspect of this architecture might have pointed the authors' comment in the report on the completed first phase of construction. They wrote in it that in the case of the offices, they were inspired by monastic cells or prison cells. (7) Asceticism as a characteristic of a museum worker? Here, it will also be good to compare the entrance and the resulting integration after several years. However, let us return to the shaping of the museum's internal layout. Vertical communication between the ground floor and the first floor of the deanery is ensured by both stairs and an elevator. I think that the latter is too robust. I am not a technician, so I do not know whether necessity played a role in that, but the internal metal structure feels unnecessary to me. Rather, I would expect a lightness that is appropriate for the exhibited works of art.

The first floor primarily opens with an art gallery organized into two rooms in the form of containers, cleaved in the enfilade line. On the walls of the containers, interpreted as having metal elements without color - i.e., black, the paintings are hung similarly to a classical gallery. The insertion is set back from the wall, thus allowing for air circulation around the walls; I am left to wonder how the paintings will fare. A textile cabinet has also been shaped into the form of a container in the Heraldic Hall, distinguished by its decor from the other exhibition rooms. Glass found its use in the form of delicate walls for paintings or sculptures or in the form of dematerialized pedestals and showcases. Compared to these achievements, the halls on the ground floor for temporary exhibitions feel somewhat awkward. Especially the panels made of perforated sheet metal create disturbing optical effects.

The beams of glass slits on the terrace above the New Hall allude to a completely differently arranged exhibition. They are not only directed at the deanery building with the tower and the chapel of St. Barbara; it is not merely external symbolism. At the level of the ground floor of the tower, illuminated glass cylinders display monstrances and chalices, arranged into a planetary system of a kind of trine (three monstrances) surrounded by chalices. The installation faithfully adheres to the exhibition of the work of Jože Plečnik from 1996 at Prague Castle when the chalices he designed in glass and light-illuminated tubes created an unforgettable magical atmosphere.

Although the former deanery has not changed much in appearance from Václav Square except for the colonnade closed with large glass panes, part of the railing of the Mozart Wing terrace, or the doors, new elements entered the courtyard of the former deanery in the form of large glass panels with manipulated images of the exhibited works of art and metal benches with steel mesh, which, as far as I can judge, are not very comfortable for lounging. Only from the balcony can one examine in detail the recessed concrete terrace of the medieval well in the middle of the courtyard. The new architecture thus acquired a restrained form from the square through transparent glass, a concrete pedestal for the statue, or movable furnishings. The architectural line of the design, viewed from this perspective, sank into the organism itself. Its last expression became the arrangement of the exhibition made accessible in September in the chapel of St. John the Baptist. However, the showcase concept and installation of the group of Christ on the Mount of Olives is not as convincing as other parts of the museum. Experience will show how this exclusive architecture is able to cope with everyday operations. It will also show whether the deliberate "ruthlessness" or severity of this architecture will be cushioned by a "merciful" cushioning, as in the case of the concrete bench at the museum cloakroom. In this context, we can find a parallel, albeit unconstructed, in the recent past. In the competition proposal for the extension of the Old Town Hall in Prague (1987), Emil Přikryl suggested that the councilors would be able to see directly from the meeting room the sculpture of Jan Hus and the Týn Church. These moral appeals were to be emphasized by "ruthless" haptic perception. In the meeting room, concrete tables and benches were planned so that the elected representatives would not enjoy the power too much. It is worth considering to whom and how the concrete benches in the case of the Archdiocesan Museum are intended.

According to the outcome of this experiment, a decision will likely be made on how the profile of other parts of the museum will look - particularly the rehabilitation of the Gothic cloister. Perhaps this will also lead to a thorough fulfillment of the ideas of architect Jan Sokol, which would be in the order of the applied architectural line of restoration of this part of the national cultural monument of the former Olomouc castle.

Notes:

AUTHOR'S REPORT

The complex of the Archdiocesan Museum is realized based on the winning design from the architectural competition from 1998. The competition was announced by the Museum of Art in Olomouc, which succeeded in the tender for the construction and establishment of the Archdiocesan Museum. The Archdiocesan Museum is located in the complex of the so-called Přemysl Castle - a national cultural monument. The buildings of the Romanesque bishopric, capitular deanery, and economic yard collectively create a composite of forms that radiate along the organic line of the walls. The design respected all preserved styles from Romanesque to the twentieth century. The reconstructed and restored collation of the original structures includes new interventions that are reduced to elements functionally and operationally necessary. The new objects are clearly differentiated from the original constructions and pass through the interior and exterior of the entire complex. Three materials supporting the contrasting atmosphere - new versus old: concrete, steel, and glass - were used in their creation. The original "old" structures have been restored to their pure form, while the "new" ones are permeated with a system of modern functions and technologies. The most prominent new intervention into the established structure of the monument is the proposed operational linking of the capitular deanery and the bishop's palace, formed as an embedded reinforced concrete object, hidden behind the wall on the courtyard terrace. Another significant volume is the social hall. Like all added new elements, the social hall is concentrated into one object, including construction and technology. An important component is the movable partition, which allows fine-tuning of the hall's acoustics (for spoken word, theatre, chamber music, cinema) and simultaneously creates various scenographic configurations. The other inserted elements are positioned for the service operations of the museum. In the old shell are scattered new steel and concrete organisms that may increase, decrease, or be replaced by another internal tissue for new life.

Technology

An independent issue was the technical solutions of several elements that are commonly placed in new constructions within walls or on walls. Since our goal was to rehabilitate the historical object as much as possible, we tried to concentrate these technical elements solely into the new constructions. Because much of the historical floors had not survived, it was possible to place most of the technology into the floors of the new structures, which are mainly made of casted concrete. Not only is there underfloor heating within them, but also a collector with backbone distribution of installations. On the upper floor, where valuable inlaid floors were found, heating is provided via heating channels in the window jambs. The lighting of the whole museum is designed in a similar manner.

Exhibition Fund

The character of the installation in the exhibition section of the museum is also in accordance with the architectural concept, where new objects and inserted elements are clearly separated from the original volumes of the historical building. Thanks to the stylistic diversity of the entire complex, it was possible to install exhibits in a related environment. This means that Romanesque and Gothic elements are placed in Romanesque and Gothic spaces. Baroque exhibits have been placed on the second floor in baroque halls. The basement mainly contains more massive opaque elements. In contrast, the exhibition on the first floor is designed to be lighter, more translucent, and strives to well present both the exhibits and not disturb the richly decorated and complex baroque interiors. An exception is made for two rooms housing the art gallery. Black boxes are installed within them to allow the presentation of a large number of paintings from the respective period. On the ground floor is a separate exhibition of the treasury, where tubes made from seamless steel pipes with safety glass have been designed. Another distinct section is short-term exhibitions. Following the entrance spaces, variable panels made of perforated sheet metal have been installed in four rooms, allowing for various configurations according to the exhibition's character. The only element firmly connected to the concrete floor is the light ramp.

The architectural concept of the Archdiocesan Museum is defined by these 10 principles:

A car full of intellectuals set off from Prague in anticipation of nothing but pleasant things. The destination - the festive opening of the Archdiocesan Museum in Olomouc. The persistent rain only amplified the increasing frustration from the clerical-military atmosphere of Olomouc. Before entering St. Wenceslas Square, a campaign vehicle from a local candidate for KDU/ČSL "coincidentally" parked there.

In front of the museum stood a crowd dressed for Sunday, similar to what I last saw in Jireš's Rodáci, the clergy shaking hands in all directions, the humid air saturated with the wine yeast of an improvised market. For the first time, I did not feel among the black-robed men as if I were among my own. On the stage, there was a farce about Mozart, followed by the main organizer and head of the museum, Dr. Zatloukal, Archbishop Graubner, and the ephemeral Minister of Culture. The dramaturgy of the ceremony transformed the visitors of the museum's opening into voters. Victors, those who managed to wrest their architecture in this local reality, who formulated theses that contrasted with the fidgeting atmosphere of a drowsy mentality clearly, loudly, and without fear, stood in the crowd. Paradoxically, they were not anxious or awkward.

I think it was Tadao Ando who said that if the genius loci is to be readable, it needs to be animated and provoked with inventive inputs. HŠH did not fear entering. Their contemporary architectural language penetrates the past with vigor. In this spontaneous act, the present appears even more precise and the past even more charming. Both actors enjoy this erotic discharge immensely, as does the viewer, who does not lose track of which part belongs to whom for even a moment. The erotic tension is further heightened by the installation of decadent fetishes of the Christian cult, dominated by the sadomasochistic symbol of the religion of love - the scene of martyrdom and crucifixion. But it is not porn; neither the present nor the past lose their dignity in this relationship.

The only obscene aspect is the color of our museums and galleries; grumpy, sputtering, or exalted old ladies (in Germany, I have not met a custodian over 40, perhaps due to high unemployment).

But even that did not spoil my extraordinary experience. Nevertheless, I apologize to HŠH for not discussing "their" museum on the way back to Prague. We were relentlessly occupied with considerations about the social significance and identity of the architect. I must admit that the opening ceremony deeply touched my professional ego.

The fact that the results of architectural work are usually presented by traders, politicians, a subret or chosen superslut has always seemed to me a manifestation of developers' limitations. Sure, there's nothing like amusing people, but why distract attention from the essence of the matter? Is there something in contemporary architecture that people recoil from? Does the architect bear some stigma that necessitates keeping him hidden from the public? And above all, will this strange state ever change when even Dr. Zatloukal, whose profession is to deal with the results of artists' work, does not consider it essential to present the key actors of an eight-year creative struggle during the presentation of the final result? Who, according to him, is actually the architect?

About Completely Green Tea or Modern Architecture in Olomouc

During the festive opening of the museum, it poured like from a watering can. So, we hid in the nearest café. A peaceful doze in the cozy room was interrupted only by the owner's astonishment over the tea order: "Green? Like completely green?" And with a shrug of the shoulders at such novelties, she brought rosehip.

The aforementioned anecdote illustrates Olomouc's tradition of rejecting contemporary architecture. We were therefore quite curious to see how team HŠH would manage to break this tradition and build upon their previous realizations. The result did not disappoint us. The tour again became the massacre we regularly experience with realizations by these Prague colleagues. We traversed the spaces of the museum, absorbing its concept, and like Alice in Wonderland, we tried to understand initially incomprehensible things with enchantment. How are full-glass exhibition showcases constructed without visible construction? How is it possible to acquire occupancy for such a beautifully atypical elevator for the disabled? In what way does the variable acoustics of the lecture hall function? What do users say about the glass surfaces of the railings, exposed concrete, and minimalist restrooms? How is all this possible - in Olomouc and at a normal fee?

HŠH does not tackle the issue of whether God is in the detail or beyond it. They profess and practice a holistic approach to creation. They consider every part of the project and construction - from concept to the last handle - as an opportunity for expression and solve it with the same degree of engagement and integrity that has no comparison in our country. And so, in slight depression and with eyes rolling, we reflect during the return journey on the magic that allows for realizing such demanding and quality architecture. We suspect the massive help of Professor Zatloukal. However, it is entirely unclear to us how it is possible to devote so much time and energy to all the atypical details of the construction while still keeping the studio afloat. To partially align ourselves with this mirror setup, we suspect our colleagues from HŠH are secretly funded by some clandestine fund for the support of contemporary architecture, which allows them to be completely economically independent of fees. But even such pseudo-explanation does not satisfy us. Only at dusk, just before Brno, do we come up with a miraculous solution: we need more buildings from HŠH. That will be better for us and for them too.

Perhaps for these reasons, until recently, any mention of the Olomouc Castle was dismissed within an esoteric circle of people; after all, what did this castle represent in the eyes of the public? What did the remnant of the Romanesque palace with the Gothic cloister and half Gothic and half modern - historicizing chapel, or the baroque, antiquated buildings of the deanery, with their past glorious history, mean for the city? For visitors and many residents alike, it was a non-existent island, situated outside of this world.

The Archdiocesan Museum is an example of what can be achieved, in a good case, through a change of owner and intervention by a higher power in the form of a visit from John Paul II, when serious consideration finally began for such an institution. The nationalized buildings were returned to the Roman Catholic Church, with the local archbishopric still managing large collections of ecclesiastical art to this day. Additionally, there was an example of earlier museum usage of part of the deanery in the 1930s. Moreover, there was an initiative institution in the form of the local Museum of Art, which won a tender in 1997 to become the founding institution of the aforementioned museum.

The solution of how to turn the various buildings into a museum institution was not left to chance and local conditions, which was certainly a good thing. In 1998, an architectural competition was announced, and a group of architects was invited who clearly understood this matter as an artistic question of coexisting contemporary architecture and new designation with the historical site (Aleš Burian and Gustav Křivinka, Mikuláš Hulec, Vít Máslo, Josef Pleskot, Viktor Rudiš, Jan Šépka). Additionally, the submitted designs were evaluated by a representative commission (Chair Miroslav Masák, members Jiří Bureš, Tomáš Černoušek, Ladislav Daniel, Zdeněk Lukeš, Michal Sborwitz, Josef Štulc, Rostislav Švácha, Pavel Zatloukal), which is not common in our country to this day. Surprisingly, in Olomouc, this was the second major architectural competition that was ultimately taken to implementation, largely thanks to the director of the Museum of Art, Pavel Zatloukal, and other museum employees. (2)

Noteworthy among the fifteen evaluated designs is the project by the AP studio of Josef Pleskot, awarded third prize, notable for its provocative entrance into the space of Václav Square, extending into the courtyard of the deanery and primarily into the economic yard, where the main exhibition hall of the museum was placed. The proposal was rejected partly because it radically addressed more than was required and beyond the capabilities of the client. On the other hand, it pointed out the limits of possibilities to approach the castle as an urban whole. The first prize was awarded to the team of Viktor and Martin Rudiš, proposing a passage between the deanery and the remnants of Zdik's Palace through a breakthrough in the Romanesque round tower, an intervention understood as unacceptable. The second prize went to the Brno team of Aleš Burian and Gustav Křivinka, inserting into the space of the curtain wall between the fortress and the deanery a passage in the form of an exhibition pavilion, rising above the existing wall with a band window along its entire length and dealing with the varying heights of the terrain using built-in stairs. The best result was ultimately awarded to the proposal by authors Petr Hájek, Tomáš Hradečný, and Jan Šépka (studio HŠH), who incorporated connecting ramps into the buildings and similarly inserted a connecting exhibition hall into the courtyard, yet with an exit to the Gothic cloister that does not exceed the medieval wall. From the beginning, it was pointed out that their approach draws lessons from the work of their teacher Emil Přikryl, especially from his Benedict Rejt Gallery in Lounech.

The authors wrote in the proposal justification about the "unrepeatability of the amalgamation of shapes ... developing around the organic line of the walls." They considered the circular tower with the chapel of St. Barbara as the focal point of the whole solution, reflected in the branching of slits arranged to naturally illuminate the exhibition spaces of the New Hall from above. Both outside and inside the historical buildings, they adhered to the idea of minimal interventions into the heritage substance of the objects, which, in an atmosphere inclined to a conservative approach to this monument, was positively received. Meanwhile, they considered the monuments as a repository of a structure composed of clearly differentiated new elements inserted into the historical constructions and spaces, materially based on the modernist trio: concrete, glass, metal. The commission then stated that: "The proposal is visually architecturally clean and stylistically defined in forms and materials… Sensitivity to the protection of the material substance of the monument is extraordinary and is expressed in the overall tone of the proposal." (3)

The first phase of the museum construction was completed in the summer of 2003 with the opening of its operational facilities, located in the buildings around the former economic yard of the deanery. For the professional public, this was an opportunity to see how the authors applied the idea of intervention into the historical environment through novelties, differentiated both materially and aesthetically, as indicated in the above-mentioned insertion of new architectural elements and complete spatial forms into historical constructions and spaces. The idea took on its final form of materially compact embedded boxes and containers. A showcase example is the expression "concrete" offices in the attic of the northern wing. Thus, the historical buildings retain a certain autonomy as spatial entities, where: "In the old shell, new steel and concrete organisms are scattered that may increase, decrease, or be replaced by another inner tissue for new life." (4)

Nothing changed this even with adjustments made to the original project based on construction-historical and archaeological research. Outwardly, these changes were most pronounced in the case of the connecting exhibition hall, called the New Hall. The original design had planned for the entire space of the courtyard to be filled from the walls of the capitular deanery to the fortress wall; however, in the end, the structure leaves a narrow passage between the wall and the inserted new form, highlighting both the medieval fortification and the insertion in the form of the concrete body with a terrace.

A similar approach was tested by studio HŠH in Olomouc during the reconstruction of Upper Square and its paving, where they preserved the diverse structure of historical origins, which they simply repaired and into which they introduced new elements in the form of furnishings or partial interventions (metal plates, city model). During this project, they experienced the provinciality of Olomouc when they encountered criticism from both parts of the public and from some politicians and representatives of heritage protection. They did not hesitate to express a certain skepticism about the acceptance their realization received: "The square is done; the cries are slowly fading - the city begins to reconcile with its square, repairing the fountains and columns, and starts to return to its slow Hanak tempo." This means, among other things, "killing space," based on an incapacity to use the public emptiness of the city and the living room with a repaired, past-imprinted carpet, as they pondered over the Upper Square issue in studio HŠH. (5)

In the case of the Archdiocesan Museum, as indicated by Petr Rezek and Rostislav Švácha in the texts on the occasion of the opening of the first phase, they seem to have successfully identified the basic framework for the overall intervention into historical objects. While Rezek thinks of the installation in connection with Scarpa as a reinterpretation of a work of art in a predominantly historical gallery and museum space, Švácha emphasizes the concept of the architectural line in Scarpa, meaning a unifying and simultaneously fundamental idea of the project that determines what and how should be done, altered, removed, or preserved to avoid deforming the architectural work directed at revitalizing the monument. (6)

As we walk through the rooms of the recently opened Olomouc museum, we can clearly recognize the aforementioned aspirations. The axis became the connection of the former capitular deanery with the remnants of Zdik's Palace, inserted with the New Hall in the courtyard, accessible via concrete ramps. This concrete insertion defines the shape of part of the basement, connected to the neighboring Gothic cellar. Even on the ground floor, some areas of the exhibition are dedicated to the presentation of the development of the building (the carriage house). The first floor is more modest from this perspective, which results from a greater degree of preservation of historical elements. Present custodians will properly instruct the visitor in this regard to wear the well-known "castle" slippers as they will traverse historical, albeit chronologically recent, interiors (the Heraldic Hall from the 19th century).

In terms of materials, it is the concrete walls, floors, and ceilings in the basement and ground floor that clearly delineate the present, which seems to levitate above or in the neighborhood of older constructions. Even the connecting concrete tunnel to the old cellar rooms feels naturally integrated, as though it had always been there. These vectors assist the visitor in independently navigating the tour. In the second phase, the principle of boxes or containers, organisms of the present, was similarly applied, if we adhere to the architects’ argument. This is evident in the service facilities - restrooms and cloakrooms. These are made of stainless steel, a relatively exclusive but unforgiving material. Unforgiving enough that I do not envy the staff the maintenance or service of these gems. It is basically "offensive" architecture, or architecture against "architecture," against functionality-oriented architecture, possibly in the authors' view of a primitive servility that could lead to an anonymous museum environment, thereby assigning a certain degree of anonymity to the exhibited works of art. It is precisely the interaction between the exclusivity of architecture and the exclusivity of works of art that offers a certain orientation in the value hierarchy of the applied architecture. Perhaps Pavel Zatloukal’s reaction to the resulting form of contemporary architectural intervention in the Archdiocesan Museum, as an architecture of "Narcissus with closed eyes" (Architect No. 9 / 2006), stems from the tension that arises between intentions, real possibilities, and acceptance of the final work.

But are not these shortcomings (or others of which I am unaware) among those elements of organisms, of which some will surely perish while other parts flourish? The same applies to the acute-angled and robust handles, glass railings, metal grips, "concrete" shelves, or scarcely openable skylights of the museum offices. Is everything wrong, or will users learn to coexist with it just as we will learn to coexist with that "architecture" whose only ambition is to serve? Or is this extravagance meant for fellow architects, the public, and the media? After all, that would not be worth the time, I tell myself. Instead, let us consider the museum of artworks in the context of their staging and the architecture subordinate to it. What kind of scene did the architects create here for works of art and what for visitors? Is the chosen approach effective?

The exhibited works of art did not arise for such a mode of presentation; they celebrated faith in God. They were often placed in different conditions that are, today, gone. Something of the monumentality is carried within the spaces treated in exposed concrete, formed of glass or black-painted sheets. The robustness of the elements and the material of the boxes indicates that we encounter something unusual here. Even the parade of Madonnas in the New Hall, made of concrete and lit from above by glass slits, feels so unreal, as if it were the dream of an art lover in delirium. The fragility of the sculptures of the High Middle Ages is reflected in the form of a filigree concrete shell.

To the superhuman dimension or ascetic position of the non-human aspect of this architecture might have pointed the authors' comment in the report on the completed first phase of construction. They wrote in it that in the case of the offices, they were inspired by monastic cells or prison cells. (7) Asceticism as a characteristic of a museum worker? Here, it will also be good to compare the entrance and the resulting integration after several years. However, let us return to the shaping of the museum's internal layout. Vertical communication between the ground floor and the first floor of the deanery is ensured by both stairs and an elevator. I think that the latter is too robust. I am not a technician, so I do not know whether necessity played a role in that, but the internal metal structure feels unnecessary to me. Rather, I would expect a lightness that is appropriate for the exhibited works of art.

The first floor primarily opens with an art gallery organized into two rooms in the form of containers, cleaved in the enfilade line. On the walls of the containers, interpreted as having metal elements without color - i.e., black, the paintings are hung similarly to a classical gallery. The insertion is set back from the wall, thus allowing for air circulation around the walls; I am left to wonder how the paintings will fare. A textile cabinet has also been shaped into the form of a container in the Heraldic Hall, distinguished by its decor from the other exhibition rooms. Glass found its use in the form of delicate walls for paintings or sculptures or in the form of dematerialized pedestals and showcases. Compared to these achievements, the halls on the ground floor for temporary exhibitions feel somewhat awkward. Especially the panels made of perforated sheet metal create disturbing optical effects.

The beams of glass slits on the terrace above the New Hall allude to a completely differently arranged exhibition. They are not only directed at the deanery building with the tower and the chapel of St. Barbara; it is not merely external symbolism. At the level of the ground floor of the tower, illuminated glass cylinders display monstrances and chalices, arranged into a planetary system of a kind of trine (three monstrances) surrounded by chalices. The installation faithfully adheres to the exhibition of the work of Jože Plečnik from 1996 at Prague Castle when the chalices he designed in glass and light-illuminated tubes created an unforgettable magical atmosphere.

Although the former deanery has not changed much in appearance from Václav Square except for the colonnade closed with large glass panes, part of the railing of the Mozart Wing terrace, or the doors, new elements entered the courtyard of the former deanery in the form of large glass panels with manipulated images of the exhibited works of art and metal benches with steel mesh, which, as far as I can judge, are not very comfortable for lounging. Only from the balcony can one examine in detail the recessed concrete terrace of the medieval well in the middle of the courtyard. The new architecture thus acquired a restrained form from the square through transparent glass, a concrete pedestal for the statue, or movable furnishings. The architectural line of the design, viewed from this perspective, sank into the organism itself. Its last expression became the arrangement of the exhibition made accessible in September in the chapel of St. John the Baptist. However, the showcase concept and installation of the group of Christ on the Mount of Olives is not as convincing as other parts of the museum. Experience will show how this exclusive architecture is able to cope with everyday operations. It will also show whether the deliberate "ruthlessness" or severity of this architecture will be cushioned by a "merciful" cushioning, as in the case of the concrete bench at the museum cloakroom. In this context, we can find a parallel, albeit unconstructed, in the recent past. In the competition proposal for the extension of the Old Town Hall in Prague (1987), Emil Přikryl suggested that the councilors would be able to see directly from the meeting room the sculpture of Jan Hus and the Týn Church. These moral appeals were to be emphasized by "ruthless" haptic perception. In the meeting room, concrete tables and benches were planned so that the elected representatives would not enjoy the power too much. It is worth considering to whom and how the concrete benches in the case of the Archdiocesan Museum are intended.

According to the outcome of this experiment, a decision will likely be made on how the profile of other parts of the museum will look - particularly the rehabilitation of the Gothic cloister. Perhaps this will also lead to a thorough fulfillment of the ideas of architect Jan Sokol, which would be in the order of the applied architectural line of restoration of this part of the national cultural monument of the former Olomouc castle.

Martin Strakoš

Notes:

- The history of Olomouc Castle, the Romanesque palace, and the method of heritage restoration see Pavel Michna - Miloslav Pojsl, The Romanesque Palace at Olomouc Castle. Archaeology and Heritage Restoration. Museum and Local History Society in Brno. Brno 1988; National Cultural Monument Přemyslovský Palace in Olomouc. I. Guide - II. Exhibition Catalogue. Regional Local History Museum - Regional Gallery of Visual Arts in Olomouc. Olomouc 1988. The current state of knowledge is summarized in the publication Archdiocesan Museum in Olomouc - Guide. Museum of Art in Olomouc. Olomouc 2006.

- Competition - Archdiocesan Museum in Olomouc, Architect XLV (I), 1999, No. 3, pp. 57-63.

- From the jury's evaluation, Architect XLV (I), 1999, No. 3, pp. 60.

- Author's report, Architect IL (V), 2003, No. 9, pp. 26.

- Hájek Petr - Šépka Jan: City, Space, and Life, Building 9., 2002, pp. 58.

- See Petr Rezek: On the subject of installations: Carlo Scarpa as an example. Rostislav Švácha: Elevation of a monument by modern architecture, both Architect IL (V), 2003, No. 9, pp. 24-25 and 36.

- 7. see note No. 4, p. 27

AUTHOR'S REPORT

The complex of the Archdiocesan Museum is realized based on the winning design from the architectural competition from 1998. The competition was announced by the Museum of Art in Olomouc, which succeeded in the tender for the construction and establishment of the Archdiocesan Museum. The Archdiocesan Museum is located in the complex of the so-called Přemysl Castle - a national cultural monument. The buildings of the Romanesque bishopric, capitular deanery, and economic yard collectively create a composite of forms that radiate along the organic line of the walls. The design respected all preserved styles from Romanesque to the twentieth century. The reconstructed and restored collation of the original structures includes new interventions that are reduced to elements functionally and operationally necessary. The new objects are clearly differentiated from the original constructions and pass through the interior and exterior of the entire complex. Three materials supporting the contrasting atmosphere - new versus old: concrete, steel, and glass - were used in their creation. The original "old" structures have been restored to their pure form, while the "new" ones are permeated with a system of modern functions and technologies. The most prominent new intervention into the established structure of the monument is the proposed operational linking of the capitular deanery and the bishop's palace, formed as an embedded reinforced concrete object, hidden behind the wall on the courtyard terrace. Another significant volume is the social hall. Like all added new elements, the social hall is concentrated into one object, including construction and technology. An important component is the movable partition, which allows fine-tuning of the hall's acoustics (for spoken word, theatre, chamber music, cinema) and simultaneously creates various scenographic configurations. The other inserted elements are positioned for the service operations of the museum. In the old shell are scattered new steel and concrete organisms that may increase, decrease, or be replaced by another internal tissue for new life.

Technology

An independent issue was the technical solutions of several elements that are commonly placed in new constructions within walls or on walls. Since our goal was to rehabilitate the historical object as much as possible, we tried to concentrate these technical elements solely into the new constructions. Because much of the historical floors had not survived, it was possible to place most of the technology into the floors of the new structures, which are mainly made of casted concrete. Not only is there underfloor heating within them, but also a collector with backbone distribution of installations. On the upper floor, where valuable inlaid floors were found, heating is provided via heating channels in the window jambs. The lighting of the whole museum is designed in a similar manner.

Exhibition Fund

The character of the installation in the exhibition section of the museum is also in accordance with the architectural concept, where new objects and inserted elements are clearly separated from the original volumes of the historical building. Thanks to the stylistic diversity of the entire complex, it was possible to install exhibits in a related environment. This means that Romanesque and Gothic elements are placed in Romanesque and Gothic spaces. Baroque exhibits have been placed on the second floor in baroque halls. The basement mainly contains more massive opaque elements. In contrast, the exhibition on the first floor is designed to be lighter, more translucent, and strives to well present both the exhibits and not disturb the richly decorated and complex baroque interiors. An exception is made for two rooms housing the art gallery. Black boxes are installed within them to allow the presentation of a large number of paintings from the respective period. On the ground floor is a separate exhibition of the treasury, where tubes made from seamless steel pipes with safety glass have been designed. Another distinct section is short-term exhibitions. Following the entrance spaces, variable panels made of perforated sheet metal have been installed in four rooms, allowing for various configurations according to the exhibition's character. The only element firmly connected to the concrete floor is the light ramp.

The architectural concept of the Archdiocesan Museum is defined by these 10 principles:

- Respect for the authenticity of individual historical units and their details.

- Minimization of new interventions.

- The principle of inserting new elements clearly differentiated from old parts.

- Limitation of materials for new elements to three basic ones - concrete, metal, glass - a clear motto that runs throughout the exhibition, including exteriors.

- Respect and support for the hierarchy of existing entrances to the complex.

- New functional uses of existing objects are proposed with regard to their spatial limits.

- The connection between the capitular deanery and the Romanesque bishopric refers to the existing urban solution and does not overshadow the circular tower from a northern view.

- The connection is used not only as communication but also as a pathway - an exhibition.

- Inner courtyards and yards are conceived as a whole and unified by the materials used (grass, stone paving, concrete).

- Exhibitions, with the exception of the first floor of the Romanesque bishopric, are barrier-free.

Premiere Without a Director

Have you ever been to a movie premiere where they presented everyone but the director? Well, listen to my story.A car full of intellectuals set off from Prague in anticipation of nothing but pleasant things. The destination - the festive opening of the Archdiocesan Museum in Olomouc. The persistent rain only amplified the increasing frustration from the clerical-military atmosphere of Olomouc. Before entering St. Wenceslas Square, a campaign vehicle from a local candidate for KDU/ČSL "coincidentally" parked there.

In front of the museum stood a crowd dressed for Sunday, similar to what I last saw in Jireš's Rodáci, the clergy shaking hands in all directions, the humid air saturated with the wine yeast of an improvised market. For the first time, I did not feel among the black-robed men as if I were among my own. On the stage, there was a farce about Mozart, followed by the main organizer and head of the museum, Dr. Zatloukal, Archbishop Graubner, and the ephemeral Minister of Culture. The dramaturgy of the ceremony transformed the visitors of the museum's opening into voters. Victors, those who managed to wrest their architecture in this local reality, who formulated theses that contrasted with the fidgeting atmosphere of a drowsy mentality clearly, loudly, and without fear, stood in the crowd. Paradoxically, they were not anxious or awkward.

I think it was Tadao Ando who said that if the genius loci is to be readable, it needs to be animated and provoked with inventive inputs. HŠH did not fear entering. Their contemporary architectural language penetrates the past with vigor. In this spontaneous act, the present appears even more precise and the past even more charming. Both actors enjoy this erotic discharge immensely, as does the viewer, who does not lose track of which part belongs to whom for even a moment. The erotic tension is further heightened by the installation of decadent fetishes of the Christian cult, dominated by the sadomasochistic symbol of the religion of love - the scene of martyrdom and crucifixion. But it is not porn; neither the present nor the past lose their dignity in this relationship.

The only obscene aspect is the color of our museums and galleries; grumpy, sputtering, or exalted old ladies (in Germany, I have not met a custodian over 40, perhaps due to high unemployment).

But even that did not spoil my extraordinary experience. Nevertheless, I apologize to HŠH for not discussing "their" museum on the way back to Prague. We were relentlessly occupied with considerations about the social significance and identity of the architect. I must admit that the opening ceremony deeply touched my professional ego.

The fact that the results of architectural work are usually presented by traders, politicians, a subret or chosen superslut has always seemed to me a manifestation of developers' limitations. Sure, there's nothing like amusing people, but why distract attention from the essence of the matter? Is there something in contemporary architecture that people recoil from? Does the architect bear some stigma that necessitates keeping him hidden from the public? And above all, will this strange state ever change when even Dr. Zatloukal, whose profession is to deal with the results of artists' work, does not consider it essential to present the key actors of an eight-year creative struggle during the presentation of the final result? Who, according to him, is actually the architect?

Jaroslav Wertig (written for the magazine ARCHITEKT 9/2006)

About Completely Green Tea or Modern Architecture in Olomouc

During the festive opening of the museum, it poured like from a watering can. So, we hid in the nearest café. A peaceful doze in the cozy room was interrupted only by the owner's astonishment over the tea order: "Green? Like completely green?" And with a shrug of the shoulders at such novelties, she brought rosehip.The aforementioned anecdote illustrates Olomouc's tradition of rejecting contemporary architecture. We were therefore quite curious to see how team HŠH would manage to break this tradition and build upon their previous realizations. The result did not disappoint us. The tour again became the massacre we regularly experience with realizations by these Prague colleagues. We traversed the spaces of the museum, absorbing its concept, and like Alice in Wonderland, we tried to understand initially incomprehensible things with enchantment. How are full-glass exhibition showcases constructed without visible construction? How is it possible to acquire occupancy for such a beautifully atypical elevator for the disabled? In what way does the variable acoustics of the lecture hall function? What do users say about the glass surfaces of the railings, exposed concrete, and minimalist restrooms? How is all this possible - in Olomouc and at a normal fee?

HŠH does not tackle the issue of whether God is in the detail or beyond it. They profess and practice a holistic approach to creation. They consider every part of the project and construction - from concept to the last handle - as an opportunity for expression and solve it with the same degree of engagement and integrity that has no comparison in our country. And so, in slight depression and with eyes rolling, we reflect during the return journey on the magic that allows for realizing such demanding and quality architecture. We suspect the massive help of Professor Zatloukal. However, it is entirely unclear to us how it is possible to devote so much time and energy to all the atypical details of the construction while still keeping the studio afloat. To partially align ourselves with this mirror setup, we suspect our colleagues from HŠH are secretly funded by some clandestine fund for the support of contemporary architecture, which allows them to be completely economically independent of fees. But even such pseudo-explanation does not satisfy us. Only at dusk, just before Brno, do we come up with a miraculous solution: we need more buildings from HŠH. That will be better for us and for them too.

Antonín Novák (written for the magazine ARCHITEKT 9/2006)

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment