JOSIP PLEČNIK / SKETCHES

Plečnik's Ljubljana in architectural sketches from the private collection of Damjan Prelovšek

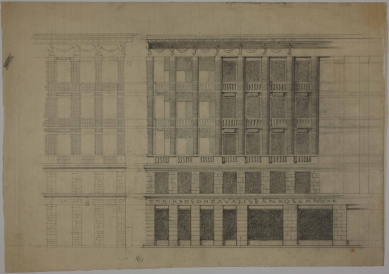

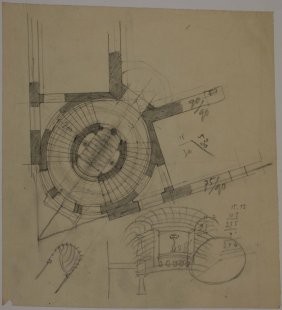

Original sketches and examples of furniture by the world-renowned Slovenian architect Josip Plečnik from the private collection of Dr. Damjan Prelovšek will be displayed from December 19, 2013, at the House of Art in Ostrava. The exhibition presents several architectural designs that Josip Plečnik devoted to his native Ljubljana, which mainly come from the period after he finished his work at Prague Castle. Drawing was the starting point for Plečnik's architecture. His natural ability for graphic expression was remarkable; with just a few small lines, he managed to convey the essence of his ideas. His admiration in this regard was also expressed by Le Corbusier. The exhibition will be opened on December 19, 2013, at 5:00 PM and will be accessible until February 16, 2014.

The exhibition presents several architectural designs that Josip Plečnik primarily dedicated to his native Ljubljana, mostly originating from the time after he completed his work at Prague Castle. It is definitely not a reminder of all the most important projects but rather a small showcase of what is found in the private collection of Dr. Damjan Prelovšek.

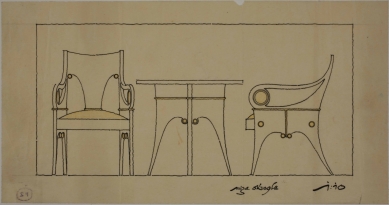

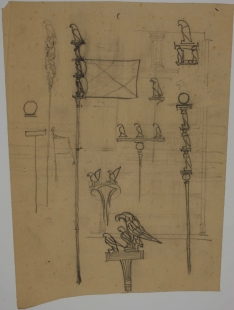

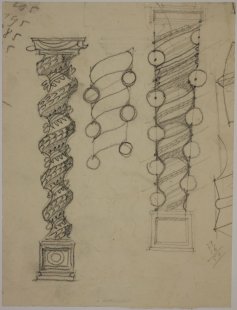

The exhibited drawings allow one to understand the method by which Josip Plečnik approached the design of his buildings or functional art objects, as a long series of sketches always preceded the final result. His natural ability for graphic expression, a trait so characteristic of his entire work, was remarkable. With just a few small strokes, he expressed the essence of his thoughts. These drawings were always a starting point for detailed work on implementation drawings and plans, which were drawn by his students under his careful supervision. A significant majority of the depicted objects were drawn to actual size and with all the details. Drawing was the starting point for Plečnik's architecture and the most important subject within his teaching. It began with exercises in drawing shadows using a technique called pencil rotation, and continued with rendering details of ancient buildings,

where Plečnik insisted on their precise execution. Thanks to such training, his students were often accepted into Le Corbusier's studio, as he greatly valued the high culture of their graphic expression

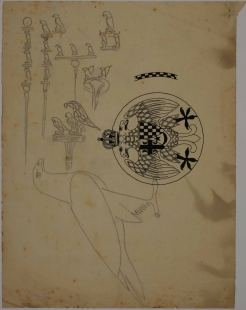

and referred to Plečnik as "le fameux dessinateur á la main tremblante". This was related to his way of controlling the line's direction through slight trembling of his hand. Plečnik exclusively used a pencil or an ink pen for drawing. Particularly interesting are his designs drawn in red ink, which thus significantly differ at first glance from the works of his assistants. Plečnik also partially colored his sketches so that the craftsmen understood correctly which materials should be used for the parts of the objects he designed. He was also able to draw in different perspectives, predominantly using cavalier perspective, and was admired for his natural ease in correctly choosing the scale of his sketches off the top of his head.

The exhibited drawings come from several sources and include some unrealized designs, such as the monument to the South Slavic king Alexander Karađorđević intended for the center of Ljubljana. The largest part is from the estate of the owner’s grandfather, Ing. Matka Prelovšek, who was the director of the city building authority and a long-time friend of Plečnik. Some sketches were purchased from the estate of Plečnik's first assistant, France Tomažič, and another part was also obtained from the estate of Plečnik's Czech student, Václav Ložek. Special thanks go to architect Miroslav Řepa, who contributed several drawings from the estate of his father, Karel Řepa, to this collection. He was the last Czech student of Plečnik, followed him to Ljubljana, and also finished his studies there.

In contrast, world experts evaluate Plečnik's work differently. It has been shown that the history of architecture in the 20th century cannot be defined so simply as it seemed until recently. In addition to the main functionalist current, there existed a handful of individuals such as the Swede Gunnar Asplund, the Greek Dimitris Pikionis, or the German Hans Döllgast, who went their own unconventional ways. Plečnik belongs to the same generation as Frank Lloyd Wright or Adolf Loos. He came from humble conditions in provincial Ljubljana and was a deeply religious artist like the Catalan Antoni Gaudí, fundamentally rather conservative. We can ask how it is possible that an architect with such a skeptical view of the new age of technological progress could bring anything positive to modern architecture? We must not forget that Plečnik was also an avant-garde author of one of the very first reinforced concrete churches. His study under Wagner, who had a more evolutionary than revolutionary approach to art, suited his nature and gave him everything he needed as an architect. The exceptionally gifted artist succeeded in adapting the classical art of antiquity to modern purposes through the Semperian theory of “cladding” (Bekleidungstheorie) of architecture without having to use the fashionable shapes of his time. He engaged with the basic themes of classical architecture, such as the relationship between ornament and structural support, the question of weight and support, proportions and rhythm, lighting of buildings, technologies of classical materials, and above all the question of how classical means can achieve maximum monumentality of a building. All of this is gaining interest again today and is becoming more relevant than ever. In an era that no longer recognizes any aesthetic norms, where everything is allowed in art, Plečnik's works act as a model example of eternal laws of beauty. When postmodernism was born in the late 1960s, many world architects traveled to Ljubljana and Prague to pay tribute to Plečnik. Everything they sought was already there, but in a more thoughtful and beautiful presentation. However, Plečnik is not a postmodernist. He cannot be easily classified into any stylistic current, but he could likely be considered a precursor of today’s renewed moderate regionalism. He was able to achieve maximum artistic expression through simple means. For example, he built his church on the Ljubljana marshes from the pipes of the city sewer system because there was no money for anything else.

Plečnik's works do not age and do not boast expensive execution. Their merit lies in a balanced concept, human scale, and perfect rhythm. They are multi-layered and interesting for anyone who seeks something additional in architecture while trying to understand its basic rules.

Damjan Prelovšek/ Ljubljana/ 2013

The exhibition presents several architectural designs that Josip Plečnik primarily dedicated to his native Ljubljana, mostly originating from the time after he completed his work at Prague Castle. It is definitely not a reminder of all the most important projects but rather a small showcase of what is found in the private collection of Dr. Damjan Prelovšek.

The exhibited drawings allow one to understand the method by which Josip Plečnik approached the design of his buildings or functional art objects, as a long series of sketches always preceded the final result. His natural ability for graphic expression, a trait so characteristic of his entire work, was remarkable. With just a few small strokes, he expressed the essence of his thoughts. These drawings were always a starting point for detailed work on implementation drawings and plans, which were drawn by his students under his careful supervision. A significant majority of the depicted objects were drawn to actual size and with all the details. Drawing was the starting point for Plečnik's architecture and the most important subject within his teaching. It began with exercises in drawing shadows using a technique called pencil rotation, and continued with rendering details of ancient buildings,

where Plečnik insisted on their precise execution. Thanks to such training, his students were often accepted into Le Corbusier's studio, as he greatly valued the high culture of their graphic expression

and referred to Plečnik as "le fameux dessinateur á la main tremblante". This was related to his way of controlling the line's direction through slight trembling of his hand. Plečnik exclusively used a pencil or an ink pen for drawing. Particularly interesting are his designs drawn in red ink, which thus significantly differ at first glance from the works of his assistants. Plečnik also partially colored his sketches so that the craftsmen understood correctly which materials should be used for the parts of the objects he designed. He was also able to draw in different perspectives, predominantly using cavalier perspective, and was admired for his natural ease in correctly choosing the scale of his sketches off the top of his head.

The exhibited drawings come from several sources and include some unrealized designs, such as the monument to the South Slavic king Alexander Karađorđević intended for the center of Ljubljana. The largest part is from the estate of the owner’s grandfather, Ing. Matka Prelovšek, who was the director of the city building authority and a long-time friend of Plečnik. Some sketches were purchased from the estate of Plečnik's first assistant, France Tomažič, and another part was also obtained from the estate of Plečnik's Czech student, Václav Ložek. Special thanks go to architect Miroslav Řepa, who contributed several drawings from the estate of his father, Karel Řepa, to this collection. He was the last Czech student of Plečnik, followed him to Ljubljana, and also finished his studies there.

Architect Josip (Jože) Plečnik and his significance for our time

Slovenian architect Josip Plečnik was born in Ljubljana in 1872, where he also died 85 years later. He did not excel in school, and it was therefore decided that he would be a successor to his father's carpentry craft in the future. Thanks to a state scholarship, he got to the industrial school in Štýrský Hradec, where he helped Professor Leopold Theyer as a draftsman for a ring road (circular city street). When his father died in 1892, Jože was still too young to take over his workshop, so he moved to Vienna, where he worked for two years in a carpentry factory. Although Plečnik had not yet completed secondary school, Otto Wagner accepted him into his studio at the Academy of Fine Arts based solely on two drawings that he brought along. However, he soon realized that he lacked fundamental technical knowledge related to architecture, which Wagner allowed him to catch up on thanks to his outstanding drawing talent, and three years later, Plečnik left school as one of the best students of his professor. He subsequently had a study stay in Italy and France, from which he returned for several months to Wagner's studio to work on the Vienna subway project. In 1900, he became independent, and at the beginning of his practice, he did not suffer from a lack of commissions. Three years later, he befriended the Viennese industrialist Johann Evangelista Zacherle, who became Plečnik's patron until he left for Prague. Thanks to Zacherle, he also entered the circles of leading Austrian Catholic intellectuals, which was crucial for his relationship with sacred architecture. His inability to make money ultimately forced him to leave Vienna, and at the urging of Jan Kotěra, his classmate from Wagner's school, he took a professorship at the Prague School of Applied Arts at the beginning of 1911, where he worked for the next ten years. After the end of World War I, artists from the Mánes Association nominated him for the position of architect of Prague Castle, which he formally held until 1935. President T. G. Masaryk greatly valued Plečnik because he managed to connect his architectural work with the essence of his philosophical teachings. The reconstruction of Prague Castle was simultaneously the artistic peak of the Slovenian artist. In 1921, Plečnik took a professorship at the newly opened University in Ljubljana. His friendship with Engineer Matko Prelovšek, the director of the city building authority, allowed him to transform Ljubljana from an Austrian provincial town into a remarkable Slovenian metropolis. He was also very active in the field of sacred architecture, which in his execution often exceeds the ideals of the Second Vatican Council. During the interwar period, Plečnik established a unique position in Slovenian architecture, which he soon lost after World War II. Because of his religious stance, he was more or less just tolerated by the new communist leaders, although they allowed him to at least build war memorials throughout Slovenia. After his death in 1957, Plečnik quickly fell into oblivion, and unfortunately, even today, his standing within the history of Slovenian architecture is not much better.In contrast, world experts evaluate Plečnik's work differently. It has been shown that the history of architecture in the 20th century cannot be defined so simply as it seemed until recently. In addition to the main functionalist current, there existed a handful of individuals such as the Swede Gunnar Asplund, the Greek Dimitris Pikionis, or the German Hans Döllgast, who went their own unconventional ways. Plečnik belongs to the same generation as Frank Lloyd Wright or Adolf Loos. He came from humble conditions in provincial Ljubljana and was a deeply religious artist like the Catalan Antoni Gaudí, fundamentally rather conservative. We can ask how it is possible that an architect with such a skeptical view of the new age of technological progress could bring anything positive to modern architecture? We must not forget that Plečnik was also an avant-garde author of one of the very first reinforced concrete churches. His study under Wagner, who had a more evolutionary than revolutionary approach to art, suited his nature and gave him everything he needed as an architect. The exceptionally gifted artist succeeded in adapting the classical art of antiquity to modern purposes through the Semperian theory of “cladding” (Bekleidungstheorie) of architecture without having to use the fashionable shapes of his time. He engaged with the basic themes of classical architecture, such as the relationship between ornament and structural support, the question of weight and support, proportions and rhythm, lighting of buildings, technologies of classical materials, and above all the question of how classical means can achieve maximum monumentality of a building. All of this is gaining interest again today and is becoming more relevant than ever. In an era that no longer recognizes any aesthetic norms, where everything is allowed in art, Plečnik's works act as a model example of eternal laws of beauty. When postmodernism was born in the late 1960s, many world architects traveled to Ljubljana and Prague to pay tribute to Plečnik. Everything they sought was already there, but in a more thoughtful and beautiful presentation. However, Plečnik is not a postmodernist. He cannot be easily classified into any stylistic current, but he could likely be considered a precursor of today’s renewed moderate regionalism. He was able to achieve maximum artistic expression through simple means. For example, he built his church on the Ljubljana marshes from the pipes of the city sewer system because there was no money for anything else.

Plečnik's works do not age and do not boast expensive execution. Their merit lies in a balanced concept, human scale, and perfect rhythm. They are multi-layered and interesting for anyone who seeks something additional in architecture while trying to understand its basic rules.

Damjan Prelovšek/ Ljubljana/ 2013

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment