Reconstruction of the Schwarzenberg and Salm Palace for the collections of the National Gallery

17 December 2004 - 13 February 2005

Internet Café of the Trade Fair Palace, Dukelských hrdinů 47, Prague 7

Publisher

Petr Šmídek

02.01.2005 08:40

Petr Šmídek

02.01.2005 08:40

Josep Lluís Mateo

Alena Šrámková

Ladislav Lábus

Roman Koucký

mateo arquitectura

Šrámková architekti, s.r.o.

Lábus AA

Roman Koucký architektonická kancelář

In the summer of last year, the most media-covered event in the field of architectural competitions took place. However, it was a invited and non-anonymous single-round affair, to which Norman Foster from England and Tadao Ando from Japan were invited. It is a fact that the first prize wouldn't even cover a monthly salary for a nanny abroad, let alone the time of renowned architects. One of them ultimately decided to take a chance on pure charity and participated. Domestic offices also didn’t have it easy. In almost all cases, these were also educators from Prague’s CTU, who used the competition conditions as a theme for students' semester projects, which tackled the task with more vitality (you can see for yourself at exhibitions held throughout the FA CTU). The goal of the competition was to find the most operationally and architecturally suitable concept for the entrance object, which includes functions necessary for entering gallery spaces while simultaneously serving as the information center for the National Gallery. The presentation showcases the individual competition proposals in the context of the project for the reconstruction of the Schwarzenberg and Salm palaces and the final proposal.

Jury: B. Fanta, M. Knížák, K. Kobosil, J. Sapák, V. Šlapeta, M. Tajč, V. Vlnas

Reviewed proposals: Roman Koucký, Ladislav Lábus, Josep Lluís Mateo, Alena Šrámková

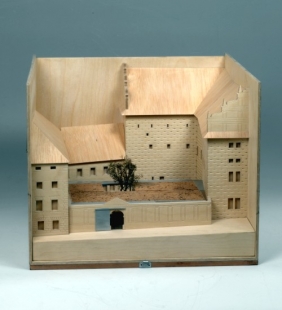

Alena Šrámková. Like all proposals, this one has only a slight impact on the overall form and texture of Hradčanského náměstí, which is given by the scale of the task and the fact that it remains hidden behind a wall. Compared to others, it seems even more introspective, as the main "service" space is immersed at the level of the basements. However, an architectural event does take place at the courtyard floor level, but it is restrained and concentrated into several accents of a smaller scale. The final expression springs from a strong sense and from the conviction that the predominant part of the architecture is prescribed by the existing morphology of the surrounding walls. The spare, minor architectural elements then connect to this prevailing order in "complete harmony" and complete the expression into a resonating whole. This impression can be characterized as a "hall under the open sky." The old facades act as walls, and the rest is dressed by new spare elements. The author herself called the space "the garden of architectural elements." The relationship between the new and the old seems balanced; one does not subordinate to the other. Function. All services are located in the central space in the basement beneath the courtyard. The advantage of the small refined courtyard (the hall under the open sky) has, however, an unfortunate counterbalance. The visitor, who is supposed to be served, will receive the first services, the first real opportunities to wait or directly to rest, only after taking an indirect path via stairs through the glass tower at the focal point of the courtyard. Then it seems that the principle endowed with undeniable architectural attractiveness suffers in utility from certain discomfort. If there is a weakness in the proposal, it is this aspect. However, once the visitor is at the basement level, the arrangement of services, although ideally indicated, is structured into logical connections. Heritage strategy. It may be overly accommodating, not only respecting but also actively protecting those elements of the surroundings that deserve it relatively little. Uncovering archaeological fragments, although it may look accommodating at first glance, can also be a source of conflicts. It is known that part of heritage doctrines prefers indifference to archaeological objects over uncovering, researching, and exhibiting. Construction. It is conservative and not eccentric. It will certainly not raise unresolvable questions.

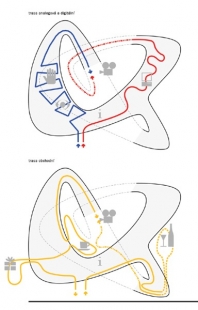

Roman Koucký. The author proposed, in his own words, a house-non-house, an infinite space that rises and falls. He created a very original, highly emotive concept of "flowing" space touching the surrounding buildings at four points. He filled the courtyard with a structure - a "gem" and a garden. The main concept of the house as a sign is supported by glass facades printed with drapery patterns and the wavy landscape of a Chinese garden. The basic operational requirements of the investor are fulfilled by the author. The design graphically addresses the entrance wall from the side of Hradčanského náměstí. This solution has been disputed from the standpoint of heritage protection. Structural solution. It is also original. The floor and ceiling slab is connected by a load-bearing steel-glass shell, which ventilates the entire structure and makes it self-supporting. The jury sees these points as problematic: although the building optically fills the entire courtyard, there is no clear and sufficiently large space for visitors immediately upon entry. The solution features an extreme length of glazed facades. This will have an impact particularly when heating and air conditioning the building during normal operations. The glass walls overlap each other, creating an interesting imaginary layering. However, the graphics on the glass, in our opinion, do not contribute to the simplicity and clear orientation for visitors. The garden solution is also expressive in the spirit of the proposal. The undulating terrain does not correspond with the Renaissance concept of the surrounding palaces. The Chinese garden appears inappropriate for the given environment. Comments on the proposal. The accentuation of greenery is controversial, especially the retention of the existing tree and the atrium of the proposed object was questioned. The connection of the roof to neighboring objects looks appealing, but it will be technically demanding; the functional connection of both palaces at the level of the first floor seems non-conflicting and meets operational requirements. The proposal is cultivated and, from the investor's perspective, offers possibilities for expansion into the underground.

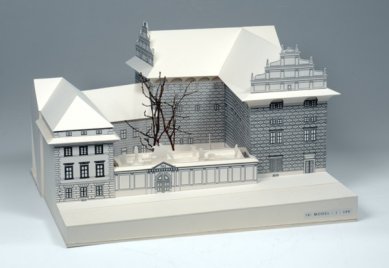

Ladislav Lábus. The proposal occupies about a third of the area designated for the courtyard. The building is positioned behind the enclosure wall and is directly accessible via the main entrance. A lower part attached to the Schwarzenberg Palace was designed by the author for a cloakroom. The ceiling of this lower section serves as a terrace and entrance to the Schwarzenberg Palace as well as access to the ramp leading from the terrace over the main building. The terrace should serve as a lookout for visitors to Hradčanského náměstí. It is architecturally enhanced by free sculptures, which would be partially visible from the outside. The surface of both structures and the courtyard paving are uniformly executed from sandstone slabs. The courtyard paving is lowered to the level of the ground floor at the connecting building. The floor of the entrance hall is two steps lower compared to the external terrain. In this hall, a ticket office and information center are located. Accesses from the hall lead to the basement, ground floor, and first floor of the Salm palace. Above the cloakroom ceiling is the entrance to the Schwarzenberg Palace. An asymmetrical arch supporting the external ramp is featured in the interior of the hall. The ceiling of the hall consists of reinforced concrete beams with a slab. The surface of the slab is to be gilded. The proposal meets operational conditions, but the created space does not match the requirements of the client in terms of size. Additionally, the architectural solution is unnecessarily historicizing. The uniform cladding of façades and courtyard paving with sandstone slabs can be considered inappropriate. The placement of sculptures on the terrace of the main building is unattainable, both in terms of scale and the fact that the NG does not own such sculptures.

History of Hradčanského náměstí

The vast area of today’s square is based on the space that formed the moat in front of Prague Castle and its outer fortifications. It likely already had today’s area upon the establishment of Hradčany in 1320, although its appearance was significantly different. Initially, modest burgher and later canon houses crouched along its perimeter, and thus the most pronounced dominant was the church of St. Benedict. Gradually, the square's image transformed, and the former Lobkowicz, now Schwarzenberg Palace, was the first to change the character of the space. Other palaces gradually appeared on the square: Griespeck’s, later reconstructed into the Archbishop's Palace in the Renaissance, and at the opposite corner, the Martinický, which was raised by one floor at the beginning of the 17th century. Next to the Lobkowicz Palace, a palatial type house emerged at the corner. In the 17th century, Prague Castle received a significant counterbalance in the building of the Thun Palace, later the Tuscan Palace, which was designed by Jean Baptiste Mathey, who also oversaw another reconstruction of the Archbishop's Palace. Not long before, the church of St. Benedict had been overshadowed by a barnabit college when viewed from the square. Only during the reign of Maria Theresa did the Castle finally undergo modifications, which had so far been separated from the square by a moat and a series of unevenly high buildings. It wasn't until 1755 that today’s honor court with grid gates was created, giving Hradčanského náměstí its final meaning. This was not changed even by later park arrangements of the space, which slightly diminished the monumentality of the Marian plague column, completed in 1736.

Until the construction of the Salm Palace, the southern part of Hradčanského náměstí appeared as the least organized. Between the palatial town and the massive building of the neighboring Schwarzenberg Palace, there were even a number of small agricultural buildings that certainly did not add to the dignity of the square. Although the construction of the connecting wall, which enclosed these unsightly spaces, took place simultaneously with the construction of the Salm Palace, its appearance was subsequently strongly altered. From the neoclassical solution, only the entrance edicule in Doric style has survived to this day; the wall was raised and architecturalized only sometime towards the end of the 19th century.

The National Gallery at Hradčanského náměstí

In 1955, the first proposal for the expansion of the National Gallery's headquarters in Prague at Hradčanského náměstí was developed. The justification for this proposal stated:

“The buildings around Hradčanského náměstí must be given a new content of high cultural values of national and international scale. This new content will be the National Gallery in Prague, collecting prominent works of national and world fine art."

It was expected that the canonical houses along the entire northern side of the square, along with the Martinický, Tuscan, and Trčka palaces, would be utilized for the National Gallery.

This ambitious plan was scrutinized from various angles in the following more than ten years. Individual objects were measured, historically investigated, exhibitions were considered, an economic analysis was performed, and a timeline was drafted. Other options were reviewed, for example, in 1962, the Salm Palace appeared among the possible objects suitable for displaying 19th-century art. The following year, the first architectural study was developed for it (K. Kunca). A design from 1967 aims to create a single unit from the canonical houses and the Sternberg Palace (V. Hilský and O. Jurenka). In 1968, the so-called House of Pages in Kanovnická Street was also considered for either the needs of the Oriental collection or the architecture collection (J. Čermák). As late as 1969, materials were gathered for a comprehensive study on the utilization of the entire Hradčanského náměstí (J. Hlavatý, K. Kunca), but then all work on the subject stopped. Most of the objects which were considered for the National Gallery gradually took on different functions with different users.

Only after 2001 did the National Gallery in Prague proactively express interest in asserting itself more significantly at Hradčanského náměstí. Initially, it acquired the Schwarzenberg Palace and subsequently the Salm Palace.

History of the Palaces

Salm (small Schwarzenberg) Palace

(No. 186/IV, Hradčany, Hradčanského náměstí 1)

The building of palatial type was created as a Neoclassical new building between 1800 and 1811. It arose on the site of small houses occupied by castle officials from the lower nobility, which were later merged into larger noble houses. Its position had long enticed the construction of a more extensive building. Karl Ignác of Sternberg wanted to build a palace here according to the project by the Baroque architect Carlo Fontana. He also sent plans of the existing buildings. The famous Roman architect did prepare the plans, but they were never executed. The reconstruction was carried out only by Archbishop Vilem Florentan, Prince Sal-Salm, who acquired the dilapidated houses in 1796. By 1811, he had a palace built according to the plans of his architect František Pávíček (Pawitschek). The Prague Archbishop is said to have built this object as an apartment building with natural apartments for his officials, but they would be truly high-standard, even luxurious apartments, where many rooms are connected through enfilades into a vast suite. The palace building has, according to the French manner, a small forecourt (cour d’honor), closed off from the square only by a massive grid with grid doors.

Schwarzenberg (Lobkowicz) Palace

(No. 185/IV, Hradčany, Hradčanského náměstí 2)

The construction of the palace, commissioned by Jan the Younger of Lobkowicz, likely began shortly after 1542, after the devastating fire of Malá Strana and Hradčany. The palace was completed before 1567, as shown by the date preserved on the sgraffito rustication, which is now hidden in the neighboring building. The building was most likely designed by the Wallachian architect Agostino Galli. The Lobkowicz family lost the palace in 1594 when Jiří of Lobkowicz was condemned for offending Emperor Rudolf II, losing his property. The palace was briefly owned by Petr Vok of Rosenberg; after his death, it was held by Jan Jiří of Švamberk and ended up in the ownership of the Eggenbergs through the White Mountain confiscations. A larger modification took place only in 1710 under Jan Kristián of Eggenberg, when the original staircase was removed and a new representative one was built in its place. After the death of Jan Kristián, the palace was inherited by Adam František of Schwarzenberg. Between 1871 and 1890, several modern interventions were made to the palace: the sgraffito was restored, the roof was covered with slate, and a neo-Renaissance enclosing wall facing Hradčanského náměstí was built according to the design of Josef Schulze. (The current form of the sgraffiti is from the years 1955-57).

Since its inception, the palace has had a significant influence on the panorama of Hradčany; even at the time of construction, the building had an impressive size and represented one of the most powerful Czech noble families with dignity. The demanding builder also matched the design of the building with a large dance hall (or feast hall) that, due to its elevation, necessitated the first use of a mezzanine in the Czech environment. With today’s three-winged layout, the builder did not originally plan; the construction was meant to be closed off with another wing towards Hradčanského náměstí.

Petr Šmídek

Jury: B. Fanta, M. Knížák, K. Kobosil, J. Sapák, V. Šlapeta, M. Tajč, V. Vlnas

Reviewed proposals: Roman Koucký, Ladislav Lábus, Josep Lluís Mateo, Alena Šrámková

Jury Statements:

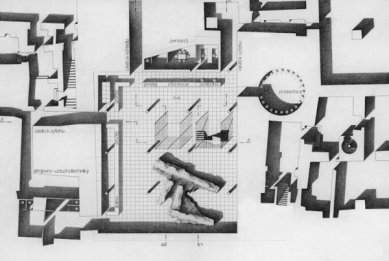

Josep L. Mateo. The entrance object is not a "house" in the true sense - the space defined vertically by the Schwarzenberg and Salm palaces is only bordered horizontally by a roof deliberately distanced from the facades. The diversity of height levels of the palaces and the courtyard terrain is abstractly rewritten by the author into a topographic floor through ramps and stairs allowing non-conflicting connections between the palaces. The ingenious structure of the roofing does not weaken the fresh and simultaneously lapidary concept - flowing space, minimum interventions into the historical building structure. A significant feature of the proposal is the use of greenery - the principle of the "hidden garden", a vegetation layer of the roof, respecting the existing tree (walnut). From the perspective of heritage protection, the concept is founded correctly, with reservations about the entry from Hradčanského náměstí - the sliding surface of the gate is an adequate sign of entrance architecturally, but from the viewpoint of heritage protection, it has been disputed. Conversely, the break in the wall at the corner by the Schwarzenberg palace is non-conflicting from the perspective of heritage protection - an optical connection of the entrance square is desirable and attractive. The proposal is highly refined, devoid of gestural excesses; it is characterized by an surprisingly consistent understanding of the site. Comments on the proposal. The accentuation of greenery is, in the opinion of the jury, controversial, especially the retention of the existing tree in the atrium of the proposed object was questioned. The connection of the roof to neighboring objects is striking, but technically demanding. Access to the cloakroom located in the basement of the Salm palace via an underground passage at Hradčanského náměstí will require securing the existing wall. The functional connection of both palaces at the level of the first floor is non-conflicting and meets operational requirements. The proposal is cultivated in execution; from the investor's perspective, it additionally offers reserves for expansion into the basement of the courtyard.Alena Šrámková. Like all proposals, this one has only a slight impact on the overall form and texture of Hradčanského náměstí, which is given by the scale of the task and the fact that it remains hidden behind a wall. Compared to others, it seems even more introspective, as the main "service" space is immersed at the level of the basements. However, an architectural event does take place at the courtyard floor level, but it is restrained and concentrated into several accents of a smaller scale. The final expression springs from a strong sense and from the conviction that the predominant part of the architecture is prescribed by the existing morphology of the surrounding walls. The spare, minor architectural elements then connect to this prevailing order in "complete harmony" and complete the expression into a resonating whole. This impression can be characterized as a "hall under the open sky." The old facades act as walls, and the rest is dressed by new spare elements. The author herself called the space "the garden of architectural elements." The relationship between the new and the old seems balanced; one does not subordinate to the other. Function. All services are located in the central space in the basement beneath the courtyard. The advantage of the small refined courtyard (the hall under the open sky) has, however, an unfortunate counterbalance. The visitor, who is supposed to be served, will receive the first services, the first real opportunities to wait or directly to rest, only after taking an indirect path via stairs through the glass tower at the focal point of the courtyard. Then it seems that the principle endowed with undeniable architectural attractiveness suffers in utility from certain discomfort. If there is a weakness in the proposal, it is this aspect. However, once the visitor is at the basement level, the arrangement of services, although ideally indicated, is structured into logical connections. Heritage strategy. It may be overly accommodating, not only respecting but also actively protecting those elements of the surroundings that deserve it relatively little. Uncovering archaeological fragments, although it may look accommodating at first glance, can also be a source of conflicts. It is known that part of heritage doctrines prefers indifference to archaeological objects over uncovering, researching, and exhibiting. Construction. It is conservative and not eccentric. It will certainly not raise unresolvable questions.

Roman Koucký. The author proposed, in his own words, a house-non-house, an infinite space that rises and falls. He created a very original, highly emotive concept of "flowing" space touching the surrounding buildings at four points. He filled the courtyard with a structure - a "gem" and a garden. The main concept of the house as a sign is supported by glass facades printed with drapery patterns and the wavy landscape of a Chinese garden. The basic operational requirements of the investor are fulfilled by the author. The design graphically addresses the entrance wall from the side of Hradčanského náměstí. This solution has been disputed from the standpoint of heritage protection. Structural solution. It is also original. The floor and ceiling slab is connected by a load-bearing steel-glass shell, which ventilates the entire structure and makes it self-supporting. The jury sees these points as problematic: although the building optically fills the entire courtyard, there is no clear and sufficiently large space for visitors immediately upon entry. The solution features an extreme length of glazed facades. This will have an impact particularly when heating and air conditioning the building during normal operations. The glass walls overlap each other, creating an interesting imaginary layering. However, the graphics on the glass, in our opinion, do not contribute to the simplicity and clear orientation for visitors. The garden solution is also expressive in the spirit of the proposal. The undulating terrain does not correspond with the Renaissance concept of the surrounding palaces. The Chinese garden appears inappropriate for the given environment. Comments on the proposal. The accentuation of greenery is controversial, especially the retention of the existing tree and the atrium of the proposed object was questioned. The connection of the roof to neighboring objects looks appealing, but it will be technically demanding; the functional connection of both palaces at the level of the first floor seems non-conflicting and meets operational requirements. The proposal is cultivated and, from the investor's perspective, offers possibilities for expansion into the underground.

Ladislav Lábus. The proposal occupies about a third of the area designated for the courtyard. The building is positioned behind the enclosure wall and is directly accessible via the main entrance. A lower part attached to the Schwarzenberg Palace was designed by the author for a cloakroom. The ceiling of this lower section serves as a terrace and entrance to the Schwarzenberg Palace as well as access to the ramp leading from the terrace over the main building. The terrace should serve as a lookout for visitors to Hradčanského náměstí. It is architecturally enhanced by free sculptures, which would be partially visible from the outside. The surface of both structures and the courtyard paving are uniformly executed from sandstone slabs. The courtyard paving is lowered to the level of the ground floor at the connecting building. The floor of the entrance hall is two steps lower compared to the external terrain. In this hall, a ticket office and information center are located. Accesses from the hall lead to the basement, ground floor, and first floor of the Salm palace. Above the cloakroom ceiling is the entrance to the Schwarzenberg Palace. An asymmetrical arch supporting the external ramp is featured in the interior of the hall. The ceiling of the hall consists of reinforced concrete beams with a slab. The surface of the slab is to be gilded. The proposal meets operational conditions, but the created space does not match the requirements of the client in terms of size. Additionally, the architectural solution is unnecessarily historicizing. The uniform cladding of façades and courtyard paving with sandstone slabs can be considered inappropriate. The placement of sculptures on the terrace of the main building is unattainable, both in terms of scale and the fact that the NG does not own such sculptures.

History of Hradčanského náměstí

The vast area of today’s square is based on the space that formed the moat in front of Prague Castle and its outer fortifications. It likely already had today’s area upon the establishment of Hradčany in 1320, although its appearance was significantly different. Initially, modest burgher and later canon houses crouched along its perimeter, and thus the most pronounced dominant was the church of St. Benedict. Gradually, the square's image transformed, and the former Lobkowicz, now Schwarzenberg Palace, was the first to change the character of the space. Other palaces gradually appeared on the square: Griespeck’s, later reconstructed into the Archbishop's Palace in the Renaissance, and at the opposite corner, the Martinický, which was raised by one floor at the beginning of the 17th century. Next to the Lobkowicz Palace, a palatial type house emerged at the corner. In the 17th century, Prague Castle received a significant counterbalance in the building of the Thun Palace, later the Tuscan Palace, which was designed by Jean Baptiste Mathey, who also oversaw another reconstruction of the Archbishop's Palace. Not long before, the church of St. Benedict had been overshadowed by a barnabit college when viewed from the square. Only during the reign of Maria Theresa did the Castle finally undergo modifications, which had so far been separated from the square by a moat and a series of unevenly high buildings. It wasn't until 1755 that today’s honor court with grid gates was created, giving Hradčanského náměstí its final meaning. This was not changed even by later park arrangements of the space, which slightly diminished the monumentality of the Marian plague column, completed in 1736.

Until the construction of the Salm Palace, the southern part of Hradčanského náměstí appeared as the least organized. Between the palatial town and the massive building of the neighboring Schwarzenberg Palace, there were even a number of small agricultural buildings that certainly did not add to the dignity of the square. Although the construction of the connecting wall, which enclosed these unsightly spaces, took place simultaneously with the construction of the Salm Palace, its appearance was subsequently strongly altered. From the neoclassical solution, only the entrance edicule in Doric style has survived to this day; the wall was raised and architecturalized only sometime towards the end of the 19th century.

The National Gallery at Hradčanského náměstí

In 1955, the first proposal for the expansion of the National Gallery's headquarters in Prague at Hradčanského náměstí was developed. The justification for this proposal stated:

“The buildings around Hradčanského náměstí must be given a new content of high cultural values of national and international scale. This new content will be the National Gallery in Prague, collecting prominent works of national and world fine art."

It was expected that the canonical houses along the entire northern side of the square, along with the Martinický, Tuscan, and Trčka palaces, would be utilized for the National Gallery.

This ambitious plan was scrutinized from various angles in the following more than ten years. Individual objects were measured, historically investigated, exhibitions were considered, an economic analysis was performed, and a timeline was drafted. Other options were reviewed, for example, in 1962, the Salm Palace appeared among the possible objects suitable for displaying 19th-century art. The following year, the first architectural study was developed for it (K. Kunca). A design from 1967 aims to create a single unit from the canonical houses and the Sternberg Palace (V. Hilský and O. Jurenka). In 1968, the so-called House of Pages in Kanovnická Street was also considered for either the needs of the Oriental collection or the architecture collection (J. Čermák). As late as 1969, materials were gathered for a comprehensive study on the utilization of the entire Hradčanského náměstí (J. Hlavatý, K. Kunca), but then all work on the subject stopped. Most of the objects which were considered for the National Gallery gradually took on different functions with different users.

Only after 2001 did the National Gallery in Prague proactively express interest in asserting itself more significantly at Hradčanského náměstí. Initially, it acquired the Schwarzenberg Palace and subsequently the Salm Palace.

History of the Palaces

Salm (small Schwarzenberg) Palace

(No. 186/IV, Hradčany, Hradčanského náměstí 1)

The building of palatial type was created as a Neoclassical new building between 1800 and 1811. It arose on the site of small houses occupied by castle officials from the lower nobility, which were later merged into larger noble houses. Its position had long enticed the construction of a more extensive building. Karl Ignác of Sternberg wanted to build a palace here according to the project by the Baroque architect Carlo Fontana. He also sent plans of the existing buildings. The famous Roman architect did prepare the plans, but they were never executed. The reconstruction was carried out only by Archbishop Vilem Florentan, Prince Sal-Salm, who acquired the dilapidated houses in 1796. By 1811, he had a palace built according to the plans of his architect František Pávíček (Pawitschek). The Prague Archbishop is said to have built this object as an apartment building with natural apartments for his officials, but they would be truly high-standard, even luxurious apartments, where many rooms are connected through enfilades into a vast suite. The palace building has, according to the French manner, a small forecourt (cour d’honor), closed off from the square only by a massive grid with grid doors.

Schwarzenberg (Lobkowicz) Palace

(No. 185/IV, Hradčany, Hradčanského náměstí 2)

The construction of the palace, commissioned by Jan the Younger of Lobkowicz, likely began shortly after 1542, after the devastating fire of Malá Strana and Hradčany. The palace was completed before 1567, as shown by the date preserved on the sgraffito rustication, which is now hidden in the neighboring building. The building was most likely designed by the Wallachian architect Agostino Galli. The Lobkowicz family lost the palace in 1594 when Jiří of Lobkowicz was condemned for offending Emperor Rudolf II, losing his property. The palace was briefly owned by Petr Vok of Rosenberg; after his death, it was held by Jan Jiří of Švamberk and ended up in the ownership of the Eggenbergs through the White Mountain confiscations. A larger modification took place only in 1710 under Jan Kristián of Eggenberg, when the original staircase was removed and a new representative one was built in its place. After the death of Jan Kristián, the palace was inherited by Adam František of Schwarzenberg. Between 1871 and 1890, several modern interventions were made to the palace: the sgraffito was restored, the roof was covered with slate, and a neo-Renaissance enclosing wall facing Hradčanského náměstí was built according to the design of Josef Schulze. (The current form of the sgraffiti is from the years 1955-57).

Since its inception, the palace has had a significant influence on the panorama of Hradčany; even at the time of construction, the building had an impressive size and represented one of the most powerful Czech noble families with dignity. The demanding builder also matched the design of the building with a large dance hall (or feast hall) that, due to its elevation, necessitated the first use of a mezzanine in the Czech environment. With today’s three-winged layout, the builder did not originally plan; the construction was meant to be closed off with another wing towards Hradčanského náměstí.

Information NG

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment