House of Cultural Living in Prague, questions of the relationship between architectural ideas and commercial practice

Every conversation, especially every meaningful dialogue about a department store like the House of Living Culture at Budějovická Square in Prague (design project 1968/9 - 1971, realization 1972-1980), will take place - whether we like it or not - on the grid of "the claim to preserve valuable solitaires" from the 60s and 70s of the twentieth century. These realizations are today documents of construction and architectural tradition, and a careful, cultivated relationship to them becomes a testimony - evidence of the maturity of society. Thirty and forty years ago, they opposed the normalization of construction and architectural unification, exceeded contemporary standards, brought architecturally valuable solutions, and after these decades of successful operation, "service" is subjected to new operational requirements and aspirations. Therefore, they urgently demand not only extensive financial investments into long-neglected maintenance (often threatening the lifespan of parts of the building), but also necessary reconstructions that would open the object for new demands in "the society of mass consumption".

We are witnessing efforts for "sustainable and cultivated" reconstruction. Let's explain what the content of such adjectives is. What does the architect pursue and what is his responsibility? He is responsible for the architectural idea embodied in the building, he is responsible for the choice of materials, he is responsible for the operation of the object. What does this responsibility mean? That the architectural idea will not suppress the operation and the operation will not suppress the idea. And that is "the matter at hand."

The monumental object of Věra Machoninová is a realization of such ideas and the "House of Living Culture" was successful in its everyday "service" to customers for this reason. It should be noted that the building was not constructed as "a commercial building" but as an exhibition area for the presentation of Czechoslovak furniture products. Like a showroom – that was the assignment. There was to be a completely different atmosphere than in an ordinary department store. On individual floors, "living spaces" were presented freely, while remaining maximally clear and functional. The visitor was deliberately guided through all the floors but could always easily orient himself, knew where he was, and how to get out. The delivery of selected goods was then on the lowest floor, linked to the underground parking and the metro entrance. One of the basic questions is then - is such a radical change in usage - from an exhibition concept to a department store - "embedded" in a successful outcome?

Already in the early nineties, changes occurred. There was to be a commercial use of both storage basements, directly accessible from the metro passage. Similar to the department store Kotva and Má, this transformation should also include a large grocery store. The architect designed, in coordination with the investor, a temporary placement of this supermarket in the third, vestibule floor – at the bottom of the interior atrium. However, this solution was then - presumably due to its connection to the outdoor parking - designated by the new owner as final.

Meanwhile, into this unique atrium, one of the basic ideas of this building was petrified – a generous open stair courtyard, accessible from the vestibule at street level, with impressive views into the floors. "Space develops from within here" and that had and has nothing to do with "the obsolescence of the interior of socialist commerce". Changes in the width of escalators, changes in color, the expansion of "sales areas", etc. - may be necessary, all this and much more is possible, but through careful adaptation, careful reconstruction, these interventions only become legitimate when they respect and follow the architectural idea.

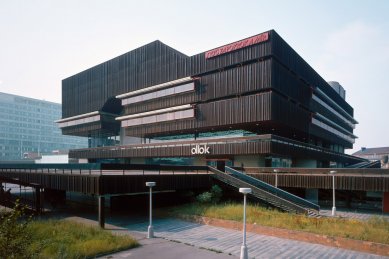

Another radical intervention that manifested in the exterior is the loss of its "levitation" - by modifying its silhouette. The cantilevering of the upper mass over the ground floor has been removed by moving the outer glazed wall to the perimeter of the building and then expanding "gastro operation" with building structures outside the outline of the building without any discernible architectural intention.

The current pressure to maximize the use of every square meter, the need to respond to increased customer and goods movement is an undeniable fact of ongoing "consumer harvests", just as the effort to offer higher comfort, a new pleasant climate (hence "lightening" of buildings from past decades of the 20th century) - all of this is legitimate. But demanding in its implementation. Demanding financially, demanding also for architecturally sensitive solutions that cannot be reduced to "maximization," "remodeling" and "revitalization" and to measuring achieved quality by the number of customers. Just for the fact that architecture petrifies values that go beyond the axiological horizon of "consumer harvests" in which retail chains operate - and with them characteristically the vocabulary of M. Velfl. In the reconstruction of these objects, the architectural idea succumbs to the current operational needs - and K. Křížová, O. Beneš, D. Karasová, and others pointed this out.

Regarding the copyright of architect V. Machoninová, the owner of the purchased painting surely does not paint his new idea over it due to a change in taste. The author, his unmistakable "handwriting" is respected – the same we could expect towards the architect and the ideas embodied in this building. And who else should at least from a purely professional perspective co-evaluate when it concerns a necessary spatial concept or a secondary solution to which an alternative can be found.

The architect clearly expressed her view on the question of "copyrights": "… it (copyright) is not an advantage, it is primarily a responsibility" - after all, a good architect perceives the relationship to his work much more as a commitment. The question arises - what will the Atmofix used on the facade do – pre-ventilated sheet metal with exceptionally specific properties that require openness and aeration if we cover it long-term with advertising banners? A separate chapter is the specific application of copyright in the preparation and realization of reconstruction. The architect, affirming the documentation with his stamp, did not address or negotiate with Ms. Machoninová, for the reason: "… so as not to be influenced", which is a fundamental contradiction with the applicable regulations of the Czech Chamber of Architects.

As for the example of a successful reconstruction of a commercial object from the sixties to seventies, among the best, we can consider the ongoing reconstruction of the interiors of the OD Kotva. Here we feel a tie to the strengths of the original architectural concept and its adaptation to the present day – an open layout extending to the display window, the openness of the interior space where the supporting structure stands out and a clear view across the full depth of the building.

The DBK department store is a telling testimony of the time in which it was created and was turned towards the future by its qualities - both should be protected and preserved – the original realization and the style in which this object was built cannot be dismissed as "conformity to the period" (M. Velfl). The point is that with "maximization of functions," "maximization of sales areas," and "revitalization," in short, successful realization of currently valid business strategies, we must not trivialize, we must not demolish the architectural idea.

In conclusion: at DBK, it has been possible to preserve its architectural essence, which is certainly a significant merit of the current owner. Further adjustments - that would align the architectural idea with function and allow its further development into the future - are still open.

We are witnessing efforts for "sustainable and cultivated" reconstruction. Let's explain what the content of such adjectives is. What does the architect pursue and what is his responsibility? He is responsible for the architectural idea embodied in the building, he is responsible for the choice of materials, he is responsible for the operation of the object. What does this responsibility mean? That the architectural idea will not suppress the operation and the operation will not suppress the idea. And that is "the matter at hand."

The monumental object of Věra Machoninová is a realization of such ideas and the "House of Living Culture" was successful in its everyday "service" to customers for this reason. It should be noted that the building was not constructed as "a commercial building" but as an exhibition area for the presentation of Czechoslovak furniture products. Like a showroom – that was the assignment. There was to be a completely different atmosphere than in an ordinary department store. On individual floors, "living spaces" were presented freely, while remaining maximally clear and functional. The visitor was deliberately guided through all the floors but could always easily orient himself, knew where he was, and how to get out. The delivery of selected goods was then on the lowest floor, linked to the underground parking and the metro entrance. One of the basic questions is then - is such a radical change in usage - from an exhibition concept to a department store - "embedded" in a successful outcome?

Already in the early nineties, changes occurred. There was to be a commercial use of both storage basements, directly accessible from the metro passage. Similar to the department store Kotva and Má, this transformation should also include a large grocery store. The architect designed, in coordination with the investor, a temporary placement of this supermarket in the third, vestibule floor – at the bottom of the interior atrium. However, this solution was then - presumably due to its connection to the outdoor parking - designated by the new owner as final.

Meanwhile, into this unique atrium, one of the basic ideas of this building was petrified – a generous open stair courtyard, accessible from the vestibule at street level, with impressive views into the floors. "Space develops from within here" and that had and has nothing to do with "the obsolescence of the interior of socialist commerce". Changes in the width of escalators, changes in color, the expansion of "sales areas", etc. - may be necessary, all this and much more is possible, but through careful adaptation, careful reconstruction, these interventions only become legitimate when they respect and follow the architectural idea.

Another radical intervention that manifested in the exterior is the loss of its "levitation" - by modifying its silhouette. The cantilevering of the upper mass over the ground floor has been removed by moving the outer glazed wall to the perimeter of the building and then expanding "gastro operation" with building structures outside the outline of the building without any discernible architectural intention.

The current pressure to maximize the use of every square meter, the need to respond to increased customer and goods movement is an undeniable fact of ongoing "consumer harvests", just as the effort to offer higher comfort, a new pleasant climate (hence "lightening" of buildings from past decades of the 20th century) - all of this is legitimate. But demanding in its implementation. Demanding financially, demanding also for architecturally sensitive solutions that cannot be reduced to "maximization," "remodeling" and "revitalization" and to measuring achieved quality by the number of customers. Just for the fact that architecture petrifies values that go beyond the axiological horizon of "consumer harvests" in which retail chains operate - and with them characteristically the vocabulary of M. Velfl. In the reconstruction of these objects, the architectural idea succumbs to the current operational needs - and K. Křížová, O. Beneš, D. Karasová, and others pointed this out.

Regarding the copyright of architect V. Machoninová, the owner of the purchased painting surely does not paint his new idea over it due to a change in taste. The author, his unmistakable "handwriting" is respected – the same we could expect towards the architect and the ideas embodied in this building. And who else should at least from a purely professional perspective co-evaluate when it concerns a necessary spatial concept or a secondary solution to which an alternative can be found.

The architect clearly expressed her view on the question of "copyrights": "… it (copyright) is not an advantage, it is primarily a responsibility" - after all, a good architect perceives the relationship to his work much more as a commitment. The question arises - what will the Atmofix used on the facade do – pre-ventilated sheet metal with exceptionally specific properties that require openness and aeration if we cover it long-term with advertising banners? A separate chapter is the specific application of copyright in the preparation and realization of reconstruction. The architect, affirming the documentation with his stamp, did not address or negotiate with Ms. Machoninová, for the reason: "… so as not to be influenced", which is a fundamental contradiction with the applicable regulations of the Czech Chamber of Architects.

As for the example of a successful reconstruction of a commercial object from the sixties to seventies, among the best, we can consider the ongoing reconstruction of the interiors of the OD Kotva. Here we feel a tie to the strengths of the original architectural concept and its adaptation to the present day – an open layout extending to the display window, the openness of the interior space where the supporting structure stands out and a clear view across the full depth of the building.

The DBK department store is a telling testimony of the time in which it was created and was turned towards the future by its qualities - both should be protected and preserved – the original realization and the style in which this object was built cannot be dismissed as "conformity to the period" (M. Velfl). The point is that with "maximization of functions," "maximization of sales areas," and "revitalization," in short, successful realization of currently valid business strategies, we must not trivialize, we must not demolish the architectural idea.

In conclusion: at DBK, it has been possible to preserve its architectural essence, which is certainly a significant merit of the current owner. Further adjustments - that would align the architectural idea with function and allow its further development into the future - are still open.

Ondřej Beneš, Oldřich Ševčík, Pavel Směták | 29.1.2011

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment