Overgrown structure at Národní

Before long, a new shopping center will be built next to the Máj department store (today's TESCO) on Spálená Street. From an urbanist perspective, this is probably a good thing, as the large gap above the National Avenue metro station was created by the unnecessary demolition of several valuable historic buildings in the 1970s. However, there is another twist: the new construction intends to match the height of the neighboring Máj, which significantly exceeded the height of the surrounding roofs in its time. If this were a result of a well-thought-out urban planning intention, it would be acceptable. But it’s different - the original zoning conditions clearly specified the maximum allowable height for the new building, which has now been exceeded by six and a half meters, translating into an additional two to even three floors in total volume. An oversight? Probably not. Rather, it is a well-established strategy to push for the largest volume possible on the most lucrative plot in the city.

But let’s return to the beginning. Spálená Street has always been one of the liveliest shopping streets in New Town. In the bold visions of Charles IV, it was one of the coronation routes for Czech kings, along which the procession was meant to walk from Prague Castle to Vyšehrad. The character of this relatively narrow street, lined with tall and narrow medieval merchant houses, brought Spálená closer to the spirit of the lively neighboring Old Town than to the calm grandeur of the New Town of Karlov. Over the years, its facades changed, but the houses and the character remained. The liveliest section was exactly where today's gap is located, where until the 1970s stood a number of Gothic-Renaissance-Baroque houses that were hidden behind more recently renovated facades. Their demolition was, therefore, a much greater tragedy than it might seem at first glance - the character of the street was significantly altered, although the commercial activity remained due to the metro station and the new department store.

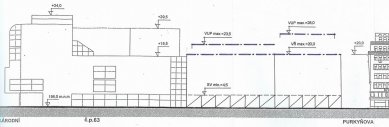

The new "little square," as the gap could be called after its modification, created a welcome open space in the midst of the tightly packed historic city. At the same time, it also "sucked away" all the energy that Spálená Street and, for that matter, the remaining originally had. To build or not to build? This question was very complicated; many people surely welcome the open space in the city out of principle and do not think much about its urban implications. Nevertheless, the new era solved the problem simply. The most lucrative plot in the city center above the busy metro station cannot be left empty - construction will occur here, the only question is what kind. Cases of vacant plots that have been thoughtlessly filled with the maximum possible volume are well known. Perhaps for this reason, the city took a responsible approach to the problem this time and organized a competition in 2001 to assess how large a building could stand here. Based on its outcome, the Department of Development of the City of Prague then issued zoning conditions, which clearly stated that the eaves of the building could reach the level of the eaves of the neighboring First Republic buildings, with the provision that there could be two receding floors above it, the second of which was meant as a potential dominant feature of the building. This would result in a building whose height (six above-ground floors plus two receding with terraces) exactly corresponds to the scale of the interwar commercial palaces, which today truly represent the visual "scale" of the tallest constructions in central Prague. Moreover, the main eaves of the new building would align with the height of the escalator hall of the Máj, which certainly coincidentally corresponds to the eaves of the opposite functionalist buildings. Simply put, the new building was supposed to fit dimensionally into its surroundings, to correct the excessive height of the upper part of Máj, and to sensitively create a new element in an urbanistically exceptionally complex environment.

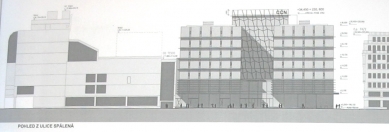

The investor behind the new construction became the company Copa of Mr. Sebastian Pawlowski, for whom the project was developed by the atelier Cigler - Marani Architects. His architectural concept was fundamentally very inventive. Instead of a large block, he proposed a system of independent "cubes," which delineate the sprawling plot and are connected in the middle by a central hall. Thus, a monolithic block would not arise, but a series of individual objects that could respond much better to the specific urban relationships of the individual parts of the new building. However, right from the start, the project had a significantly greater volume than the conditions allowed: the main eaves facing Spálená ended up two and a half (or rather three) typical floors higher, namely at the level of the main mass of the OD Máj, and the central part rose to the height of the highest rooftop addition of Máj, thus reaching the level of its hypothetical tenth floor when measured against the neighboring interwar building. This deviation from the approved conditions cannot certainly be labeled as merely cosmetic, as the entire volume of the construction thus increased by a fifth or even a quarter. The only one who repeatedly pointed out this striking fact was the National Heritage Institute. It rejected the project three times on the grounds that the zoning conditions are binding after all. The Department of Culture and Heritage Care of the Municipality ultimately decided without its consent, which unfortunately the pre-revolutionary heritage law allows, and so the construction faces no obstacles besides a few dissatisfied neighbors.

The entire case is very striking: wasn't it the city that issued these conditions five years ago? How is it possible that one department of the Municipality decides differently than another? Could it have something to do with the fact that the investor of the project, Sebastian Pawlowski, is also the new "landlord" of the Municipality, as he owns the neighboring building of the former Škodovy zavody, into which the entire Municipality is now moving? Nevertheless, from an architectural perspective, it does not matter who and why this change was allowed: the result is that on a very important site, instead of a measured building, another oversized colossus will rise, which the originally imaginative concept has turned into precisely those few extra floors.

Every city has its own scale, which should not be exceeded. The thesis that new and new floors can be continually added to buildings because this adds a "layer" of our time is purposeful and dangerous. On the contrary, the character of every city is closely linked to the building height, to the proportions of its streets, and to how visible historical landmarks like churches or public buildings still are. The interwar period reached the threshold of this "tolerance" in Prague, which fortunately manifested in rather strict regulations that no building in the center could exceed. Our time does not dwell much on such considerations, and when it does, it is evidently not taken very seriously. This is a very dangerous game: a few inappropriate interventions are enough, and the character of the city can change irreversibly. Moreover, this is not a battle between new and old architecture, as the new does not automatically mean "taller than the old," and the quality of a building is not measured by its volume. Quite the opposite is true - where purely economic considerations prevail, architecture must yield. A city that cannot distinguish quality architecture from commercial buildings is well on its way to losing itself.

But is this really what we want to do with Prague? If not, we should start caring about how the city intends to manage its architectural development. The reality is, however, grim: the urban plan is very general, and it is easy to change it purposefully; more detailed binding regulations, such as for eave height or building volume, do not exist, and moreover, there is no institution that could guarantee all this, as the municipal section of the development department has been downgraded from the originally strong and independent institution of the Chief Architect to a department without real powers. This has created the ideal space for investment adventures, such as the planned COPA Center next to Máj. Without systemic change, not much will change in the near future. Logically, the change should be initiated or at least carried out by municipal politicians: the problem, however, is that they are the ones most responsible for today's state of affairs. It might even seem that the lack of firm rules suits them. A vicious circle? In a way, yes, at least until someone or something disrupts this harmony of spheres. It is high time someone truly attempted to do that.

But let’s return to the beginning. Spálená Street has always been one of the liveliest shopping streets in New Town. In the bold visions of Charles IV, it was one of the coronation routes for Czech kings, along which the procession was meant to walk from Prague Castle to Vyšehrad. The character of this relatively narrow street, lined with tall and narrow medieval merchant houses, brought Spálená closer to the spirit of the lively neighboring Old Town than to the calm grandeur of the New Town of Karlov. Over the years, its facades changed, but the houses and the character remained. The liveliest section was exactly where today's gap is located, where until the 1970s stood a number of Gothic-Renaissance-Baroque houses that were hidden behind more recently renovated facades. Their demolition was, therefore, a much greater tragedy than it might seem at first glance - the character of the street was significantly altered, although the commercial activity remained due to the metro station and the new department store.

The new "little square," as the gap could be called after its modification, created a welcome open space in the midst of the tightly packed historic city. At the same time, it also "sucked away" all the energy that Spálená Street and, for that matter, the remaining originally had. To build or not to build? This question was very complicated; many people surely welcome the open space in the city out of principle and do not think much about its urban implications. Nevertheless, the new era solved the problem simply. The most lucrative plot in the city center above the busy metro station cannot be left empty - construction will occur here, the only question is what kind. Cases of vacant plots that have been thoughtlessly filled with the maximum possible volume are well known. Perhaps for this reason, the city took a responsible approach to the problem this time and organized a competition in 2001 to assess how large a building could stand here. Based on its outcome, the Department of Development of the City of Prague then issued zoning conditions, which clearly stated that the eaves of the building could reach the level of the eaves of the neighboring First Republic buildings, with the provision that there could be two receding floors above it, the second of which was meant as a potential dominant feature of the building. This would result in a building whose height (six above-ground floors plus two receding with terraces) exactly corresponds to the scale of the interwar commercial palaces, which today truly represent the visual "scale" of the tallest constructions in central Prague. Moreover, the main eaves of the new building would align with the height of the escalator hall of the Máj, which certainly coincidentally corresponds to the eaves of the opposite functionalist buildings. Simply put, the new building was supposed to fit dimensionally into its surroundings, to correct the excessive height of the upper part of Máj, and to sensitively create a new element in an urbanistically exceptionally complex environment.

The investor behind the new construction became the company Copa of Mr. Sebastian Pawlowski, for whom the project was developed by the atelier Cigler - Marani Architects. His architectural concept was fundamentally very inventive. Instead of a large block, he proposed a system of independent "cubes," which delineate the sprawling plot and are connected in the middle by a central hall. Thus, a monolithic block would not arise, but a series of individual objects that could respond much better to the specific urban relationships of the individual parts of the new building. However, right from the start, the project had a significantly greater volume than the conditions allowed: the main eaves facing Spálená ended up two and a half (or rather three) typical floors higher, namely at the level of the main mass of the OD Máj, and the central part rose to the height of the highest rooftop addition of Máj, thus reaching the level of its hypothetical tenth floor when measured against the neighboring interwar building. This deviation from the approved conditions cannot certainly be labeled as merely cosmetic, as the entire volume of the construction thus increased by a fifth or even a quarter. The only one who repeatedly pointed out this striking fact was the National Heritage Institute. It rejected the project three times on the grounds that the zoning conditions are binding after all. The Department of Culture and Heritage Care of the Municipality ultimately decided without its consent, which unfortunately the pre-revolutionary heritage law allows, and so the construction faces no obstacles besides a few dissatisfied neighbors.

The entire case is very striking: wasn't it the city that issued these conditions five years ago? How is it possible that one department of the Municipality decides differently than another? Could it have something to do with the fact that the investor of the project, Sebastian Pawlowski, is also the new "landlord" of the Municipality, as he owns the neighboring building of the former Škodovy zavody, into which the entire Municipality is now moving? Nevertheless, from an architectural perspective, it does not matter who and why this change was allowed: the result is that on a very important site, instead of a measured building, another oversized colossus will rise, which the originally imaginative concept has turned into precisely those few extra floors.

Every city has its own scale, which should not be exceeded. The thesis that new and new floors can be continually added to buildings because this adds a "layer" of our time is purposeful and dangerous. On the contrary, the character of every city is closely linked to the building height, to the proportions of its streets, and to how visible historical landmarks like churches or public buildings still are. The interwar period reached the threshold of this "tolerance" in Prague, which fortunately manifested in rather strict regulations that no building in the center could exceed. Our time does not dwell much on such considerations, and when it does, it is evidently not taken very seriously. This is a very dangerous game: a few inappropriate interventions are enough, and the character of the city can change irreversibly. Moreover, this is not a battle between new and old architecture, as the new does not automatically mean "taller than the old," and the quality of a building is not measured by its volume. Quite the opposite is true - where purely economic considerations prevail, architecture must yield. A city that cannot distinguish quality architecture from commercial buildings is well on its way to losing itself.

But is this really what we want to do with Prague? If not, we should start caring about how the city intends to manage its architectural development. The reality is, however, grim: the urban plan is very general, and it is easy to change it purposefully; more detailed binding regulations, such as for eave height or building volume, do not exist, and moreover, there is no institution that could guarantee all this, as the municipal section of the development department has been downgraded from the originally strong and independent institution of the Chief Architect to a department without real powers. This has created the ideal space for investment adventures, such as the planned COPA Center next to Máj. Without systemic change, not much will change in the near future. Logically, the change should be initiated or at least carried out by municipal politicians: the problem, however, is that they are the ones most responsible for today's state of affairs. It might even seem that the lack of firm rules suits them. A vicious circle? In a way, yes, at least until someone or something disrupts this harmony of spheres. It is high time someone truly attempted to do that.

Richard Biegel (written for the cultural weekly A2 - www.tydenika2.cz)

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

6 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Al Ciglerone

pav

04.09.06 08:42

to pav

Daniel John

04.09.06 05:54

Všechno je to podplacený

Jirka

04.09.06 05:04

další slon v porcelánu

robert

07.09.06 10:00

stojí za připomenutí

Vích

23.09.08 03:42

show all comments

Related articles

0

13.04.2010 | The builder of COPA Center on Národní třída is in insolvency proceedings

0

31.03.2010 | The construction of the Copa Center on Národní is standing still, the investor owes money to the archaeologists

0

16.07.2009 | At the end of July, an archaeological survey will begin at the Copa Center

0

24.10.2008 | Praha 1 will promote barrier-free access to the metro at Národní