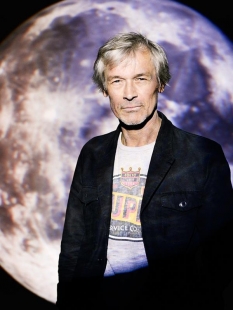

Architect Petr Stolín was born on June 25, 1958, in Svitavy. After graduating from high school in Liberec and Brno, he studied at the Faculty of Architecture at the Brno University of Technology from 1978 to 1983. Later, he worked in the studio of Pavel Švancer at Stavoprojekt Liberec and at SIAL under Karel Hubáček. Since 1993, he has been engaged in independent architectural practice. He often collaborates on projects with his brother, sculptor, and conceptual artist Jan Stolín. Since 2015, he has been running a joint studio called CUBE LOVE with Alena Mičeková, based in the experimental house ZEN in Liberec.