Cycle on young Czech architecture in UKG - Vojtěch Sigmund

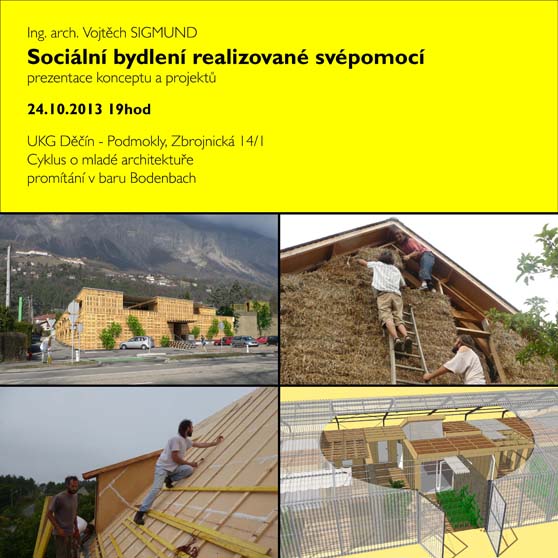

We invite you to the next installment of the series on young Czech architecture, which is taking place as part of the Stolen Gallery. Architect VOJTĚCH SIGMUND will present the topic of social housing realized through self-help. The exhibition with a lecture will take place this Thursday October 24 at 7 PM in Děčín Podmokly at the corner of Zbrojnická and Tržní Streets.

As always at UKG Děčín, the exhibition will be opened at the bulletin board, and the lecture will take place at the Bodenbach bar (about a 2-minute walk).

As always at UKG Děčín, the exhibition will be opened at the bulletin board, and the lecture will take place at the Bodenbach bar (about a 2-minute walk).

You can find more information about the exhibitions at UKG on our website.

Best regards, the SUA team

VOJTĚCH SIGMUND (*1981)

Social housing realized through self-help

Social problems in the Czech Republic are continually deepening. The number of people at risk of losing their housing or employment is rising. This reality brings with it a whole series of specific problems that need to be addressed. There is an urgent lack of state-supported housing. Commercial accommodations that currently provide housing for some groups of residents cannot, for various reasons, be a permanent solution. Living conditions in these accommodations are inadequate, and the costs of housing are disproportionately high. The state and municipalities should address this situation by building social housing. Another very current problem in the Czech Republic is the increasing number of people who are long-term unemployed. The idea of residents participating in the construction of supported housing therefore seems to be an appropriate solution. In addition to the newly created apartments, new jobs would be created, and the qualifications of the participating residents would be enhanced.

During my studies, I spent two years in Grenoble, France, where I faced an advanced stage of social problems. Both the school and our apartment were located in a suburb that ranks among the most dangerous places in France according to national statistics. Simply put, a ghetto. For example, students were often mugged leaving school in the evening hours, and the infamous French car burnings were a daily (nightly) occurrence. However, I also witnessed more serious incidents. There was a shooting in front of our house, leading to two deaths, as local drug gangs settled scores. Although the city is trying to improve the situation at the cost of massive investments, a solution is nowhere in sight and seems impossible. I understood how difficult it is to try to rectify a dire situation. How difficult it is to extinguish a fire at full power and how foolish it is to wait until such a fire breaks out instead of trying to prevent its occurrence. Everything indicates that this is precisely what is happening in the Czech Republic right now. We are waiting for a serious problem.

People at risk of social exclusion are sinking deeper into the spiral of poverty, and at the same time, society's antipathy towards certain groups of residents, especially Roma, is growing. I am deeply convinced that the current anti-Romani sentiment occurring in the Czech Republic is largely caused by the unresolved social problems. The seriousness of this social issue is reflected in numerous anti-Roma marches recently. The extreme manifestation of this social divide was, for example, the riots in Šluknov in 2011. Politicians appeared helpless. The disturbances in the Janov housing estate in Chomutov and in Šluknov have subsided, but the problem has not disappeared; the tension remains.

I realize that preventing the emergence of ghettos and social segregation is a very complex issue that engages a multitude of professions. As an architect by profession, I focus on promoting social housing as a tool to prevent the emergence of ghettos. I am surprised that only a fraction of architects in the Czech Republic address this issue. We do not have to look far for inspiration. In neighboring Austria, the construction of social housing is a widely utilized form of housing support. Exceptional projects are being developed there. It is true that our political representation ignores the need for social housing despite the fact that the European Union places significant importance on this issue. Architects are therefore waiting for an impulse from the state and are not trying to be the drivers of social change. But before the state reacts, it may be too late. That is why I am trying to devote myself to this issue, and as part of my doctoral studies at the FA CTU, I am developing the idea of social housing realized through self-help.

The fundamental idea of the participation of future residents in the construction of social housing is this: people at risk of social exclusion will gain not only housing but also work, improve their qualifications, and gain the feeling of achieving something. They can try collaboration with future neighbors, and they will likely value their newly acquired housing more. The residents of such housing should be people acutely at risk of social exclusion, especially the long-term unemployed, homeless individuals, those leaving institutional care and prisons, and people living in socially excluded Roma localities. Each group requires an individual approach, and it is also necessary to develop an individual project for each locality.

By involving these groups of residents in addressing the issue of social housing, the possibility of support from the public and, consequently, political representation is increased. They will not receive housing for free; they will work for it. The danger of this concept, which must not be overlooked, is the parallel with labor camps and the concept of forced labor. The idea of self-help-based social housing operates on the edge of moral acceptability. Therefore, it is crucial to strictly respect the voluntary participation in construction.

Social housing realized through self-help should have the following specifics:

(for clarity, they are divided into different areas)

1. Location in the city / Urbanism

It is advisable that the building be placed within a functioning urban or village structure. This measure supports the social inclusion of residents of social housing. On the other hand, placing these buildings on the outskirts of settlements or even outside of them leads to social segregation, which risks the emergence of ghettos.

This recommendation was not followed in the case of the so-called “Čunek’s hovels.” This was a media-highlighted case where families of rent defaulters were forced to relocate to the Poschlá residential complex on the outskirts of the city, which was newly built from residential and sanitary containers. The solution was criticized by the public ombudsman Otakar Motejl as “unconceptual and ineffective.” Currently, the Poschlá area can be referred to as a ghetto.

2. Scale of the building / Typology

The appropriate size of the building should be individually addressed for each project and locality. Unduly large buildings or residential complexes are more susceptible to the emergence of ghettos, which is undesirable for both the given municipality and the residents. The scale of the building should, in any case, respect the scale of the settlement structure into which the building will be inserted. Standalone family homes are not very suitable as they require larger plot areas and higher costs for building engineering networks.

3. Construction costs / Acquisition and operational

For residents of social housing, both acquisition costs and the operational costs of the building are vital. The largest part of operational costs is influenced by the energy demands of the building. For this reason, it is necessary to optimize energy consumption and to include energy savings in the design from the initial stages of project planning.

A prudent housing policy can be observed in neighboring Austria, where the number of new social housing units being built to passive standards (energy demand of less than 15 kWh/m2) is steadily increasing. In the Austrian federal state of Vorarlberg, new constructions of social housing must be built to passive standards by law.

4. Construction materials / Construction system

In general, it can be said that for the needs of self-help projects of social housing, construction techniques that require more human labor and less expensive construction materials are preferable. Conversely, more expensive and more sophisticated construction materials and technologies imply the need to use specialized companies with trained workers. An example of such a construction material is unburned clay. Another interesting option is the recycling of materials that are not primarily intended for building houses.

5. Use of self-help / Organization of construction

The choice of an appropriate level of resident participation in construction is crucial for the design. It is necessary to avoid extremes—i.e., to realize entire buildings through self-help or, conversely, not to utilize self-help at all. It is not possible to prove that the use of self-help construction technology reduces acquisition costs in all cases. On self-help construction sites, the risk of injury increases and the likelihood of poor-quality execution is higher. However, a significant benefit is the increase in the qualifications of self-help builders. We must also emphasize the positive psychological effect.

Under the current socio-economic conditions in the Czech Republic, there are at least two basic conceptual approaches:

A. Self-help reconstructions of neglected apartment buildings

An example is the self-help reconstruction of 14 apartments in the village of Dobrá Voda in Western Bohemia, which was carried out by the civic association Český západ in 2006. Professional work was performed by a construction company. Tenants participated in the following tasks: dismantling structures and plaster, transporting materials, securing the site, assisting construction work (painting, varnishing), and cleaning. The project was financed from a program for the removal of emergency situations in socially excluded Roma localities.

B. Self-help adaptations of prefabricated cells and their subsequent assembly by a professional company

So far, such a case has not been published in the Czech expert scene. In Britain, a new construction of 10 low-cost apartments built through self-help for young tenants was realized on Darwin Road in Tilbury. It involved a simple prefabricated wooden frame structure. Construction technique: training at a local technical university, work under supervision on the construction site, and manufacturing building components off-site.

The goal of my efforts is to create a manual for the construction of social housing realized through self-help. This manual could then serve for potential builders—i.e., for municipalities, non-profit organizations, or private companies. An inspiration for this manual is the handbook from the Agency for Social Inclusion in Roma localities titled: “Condition of employing 10% long-term unemployed in public contracts.” This condition was applied by the city of Most in four public contracts for the reconstruction of panel houses in the Chanov housing estate.

Vojtěch Sigmund, October 20, 2013

Best regards, the SUA team

|

VOJTĚCH SIGMUND (*1981)

Social housing realized through self-help

Social problems in the Czech Republic are continually deepening. The number of people at risk of losing their housing or employment is rising. This reality brings with it a whole series of specific problems that need to be addressed. There is an urgent lack of state-supported housing. Commercial accommodations that currently provide housing for some groups of residents cannot, for various reasons, be a permanent solution. Living conditions in these accommodations are inadequate, and the costs of housing are disproportionately high. The state and municipalities should address this situation by building social housing. Another very current problem in the Czech Republic is the increasing number of people who are long-term unemployed. The idea of residents participating in the construction of supported housing therefore seems to be an appropriate solution. In addition to the newly created apartments, new jobs would be created, and the qualifications of the participating residents would be enhanced.

During my studies, I spent two years in Grenoble, France, where I faced an advanced stage of social problems. Both the school and our apartment were located in a suburb that ranks among the most dangerous places in France according to national statistics. Simply put, a ghetto. For example, students were often mugged leaving school in the evening hours, and the infamous French car burnings were a daily (nightly) occurrence. However, I also witnessed more serious incidents. There was a shooting in front of our house, leading to two deaths, as local drug gangs settled scores. Although the city is trying to improve the situation at the cost of massive investments, a solution is nowhere in sight and seems impossible. I understood how difficult it is to try to rectify a dire situation. How difficult it is to extinguish a fire at full power and how foolish it is to wait until such a fire breaks out instead of trying to prevent its occurrence. Everything indicates that this is precisely what is happening in the Czech Republic right now. We are waiting for a serious problem.

People at risk of social exclusion are sinking deeper into the spiral of poverty, and at the same time, society's antipathy towards certain groups of residents, especially Roma, is growing. I am deeply convinced that the current anti-Romani sentiment occurring in the Czech Republic is largely caused by the unresolved social problems. The seriousness of this social issue is reflected in numerous anti-Roma marches recently. The extreme manifestation of this social divide was, for example, the riots in Šluknov in 2011. Politicians appeared helpless. The disturbances in the Janov housing estate in Chomutov and in Šluknov have subsided, but the problem has not disappeared; the tension remains.

I realize that preventing the emergence of ghettos and social segregation is a very complex issue that engages a multitude of professions. As an architect by profession, I focus on promoting social housing as a tool to prevent the emergence of ghettos. I am surprised that only a fraction of architects in the Czech Republic address this issue. We do not have to look far for inspiration. In neighboring Austria, the construction of social housing is a widely utilized form of housing support. Exceptional projects are being developed there. It is true that our political representation ignores the need for social housing despite the fact that the European Union places significant importance on this issue. Architects are therefore waiting for an impulse from the state and are not trying to be the drivers of social change. But before the state reacts, it may be too late. That is why I am trying to devote myself to this issue, and as part of my doctoral studies at the FA CTU, I am developing the idea of social housing realized through self-help.

The fundamental idea of the participation of future residents in the construction of social housing is this: people at risk of social exclusion will gain not only housing but also work, improve their qualifications, and gain the feeling of achieving something. They can try collaboration with future neighbors, and they will likely value their newly acquired housing more. The residents of such housing should be people acutely at risk of social exclusion, especially the long-term unemployed, homeless individuals, those leaving institutional care and prisons, and people living in socially excluded Roma localities. Each group requires an individual approach, and it is also necessary to develop an individual project for each locality.

By involving these groups of residents in addressing the issue of social housing, the possibility of support from the public and, consequently, political representation is increased. They will not receive housing for free; they will work for it. The danger of this concept, which must not be overlooked, is the parallel with labor camps and the concept of forced labor. The idea of self-help-based social housing operates on the edge of moral acceptability. Therefore, it is crucial to strictly respect the voluntary participation in construction.

Social housing realized through self-help should have the following specifics:

(for clarity, they are divided into different areas)

1. Location in the city / Urbanism

It is advisable that the building be placed within a functioning urban or village structure. This measure supports the social inclusion of residents of social housing. On the other hand, placing these buildings on the outskirts of settlements or even outside of them leads to social segregation, which risks the emergence of ghettos.

This recommendation was not followed in the case of the so-called “Čunek’s hovels.” This was a media-highlighted case where families of rent defaulters were forced to relocate to the Poschlá residential complex on the outskirts of the city, which was newly built from residential and sanitary containers. The solution was criticized by the public ombudsman Otakar Motejl as “unconceptual and ineffective.” Currently, the Poschlá area can be referred to as a ghetto.

2. Scale of the building / Typology

The appropriate size of the building should be individually addressed for each project and locality. Unduly large buildings or residential complexes are more susceptible to the emergence of ghettos, which is undesirable for both the given municipality and the residents. The scale of the building should, in any case, respect the scale of the settlement structure into which the building will be inserted. Standalone family homes are not very suitable as they require larger plot areas and higher costs for building engineering networks.

3. Construction costs / Acquisition and operational

For residents of social housing, both acquisition costs and the operational costs of the building are vital. The largest part of operational costs is influenced by the energy demands of the building. For this reason, it is necessary to optimize energy consumption and to include energy savings in the design from the initial stages of project planning.

A prudent housing policy can be observed in neighboring Austria, where the number of new social housing units being built to passive standards (energy demand of less than 15 kWh/m2) is steadily increasing. In the Austrian federal state of Vorarlberg, new constructions of social housing must be built to passive standards by law.

4. Construction materials / Construction system

In general, it can be said that for the needs of self-help projects of social housing, construction techniques that require more human labor and less expensive construction materials are preferable. Conversely, more expensive and more sophisticated construction materials and technologies imply the need to use specialized companies with trained workers. An example of such a construction material is unburned clay. Another interesting option is the recycling of materials that are not primarily intended for building houses.

5. Use of self-help / Organization of construction

The choice of an appropriate level of resident participation in construction is crucial for the design. It is necessary to avoid extremes—i.e., to realize entire buildings through self-help or, conversely, not to utilize self-help at all. It is not possible to prove that the use of self-help construction technology reduces acquisition costs in all cases. On self-help construction sites, the risk of injury increases and the likelihood of poor-quality execution is higher. However, a significant benefit is the increase in the qualifications of self-help builders. We must also emphasize the positive psychological effect.

Under the current socio-economic conditions in the Czech Republic, there are at least two basic conceptual approaches:

A. Self-help reconstructions of neglected apartment buildings

An example is the self-help reconstruction of 14 apartments in the village of Dobrá Voda in Western Bohemia, which was carried out by the civic association Český západ in 2006. Professional work was performed by a construction company. Tenants participated in the following tasks: dismantling structures and plaster, transporting materials, securing the site, assisting construction work (painting, varnishing), and cleaning. The project was financed from a program for the removal of emergency situations in socially excluded Roma localities.

B. Self-help adaptations of prefabricated cells and their subsequent assembly by a professional company

So far, such a case has not been published in the Czech expert scene. In Britain, a new construction of 10 low-cost apartments built through self-help for young tenants was realized on Darwin Road in Tilbury. It involved a simple prefabricated wooden frame structure. Construction technique: training at a local technical university, work under supervision on the construction site, and manufacturing building components off-site.

The goal of my efforts is to create a manual for the construction of social housing realized through self-help. This manual could then serve for potential builders—i.e., for municipalities, non-profit organizations, or private companies. An inspiration for this manual is the handbook from the Agency for Social Inclusion in Roma localities titled: “Condition of employing 10% long-term unemployed in public contracts.” This condition was applied by the city of Most in four public contracts for the reconstruction of panel houses in the Chanov housing estate.

Vojtěch Sigmund, October 20, 2013

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment