Ernst Wiesner in Great Britain

Insight into the life of Ernst Wiesner in the early years of his exile

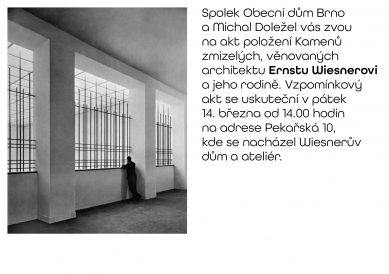

This article draws on a lecture that took place on August 31, 2024, as part of the Jewish culture festival Štetl Fest. At the same time, it is published on the occasion of laying the Stolpersteine for the Ernst Wiesner family in Brno, in front of the house at 10 Pekařská Street.

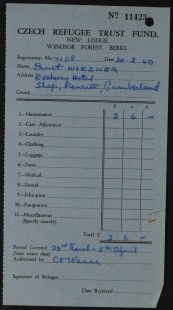

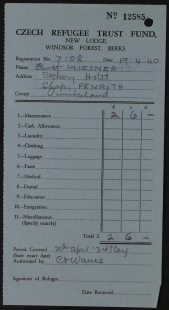

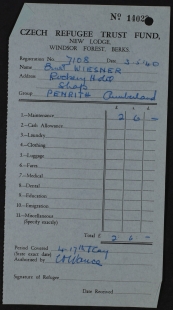

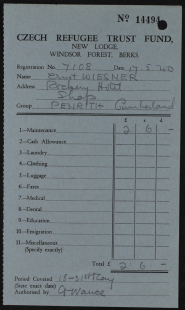

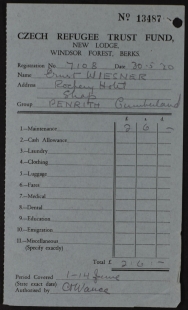

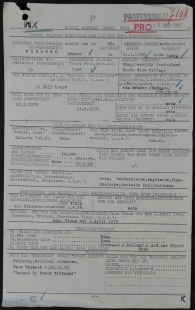

In the British National Archives, under catalogue number HO 334/359/22013, there is a file titled Wiesner Arnošt: British Subject. This file contains a total of 137 sheets, mostly made up of letters between Wiesner and the Czech Refugee Fund, as well as applications for maintenance, forms, several newspaper articles, etc., which can be dated from June 1939 to February 1941.

The oldest document stored here is a form from June 23, 1939, which Wiesner filled out for the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia. This is also the date of his registration in Britain as a Czechoslovak refugee, based on which he received registration number 7108. This official document contains a wealth of valuable information about the first months of Wiesner's exile.

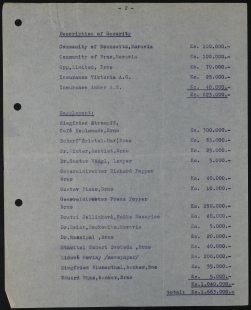

Wiesner stated in the document, among other things, his residence at 123 Eyre Court, Finchley, Rd. London N.W.8 – most likely one of his first addresses in Britain. He also stated that – at this time still – he had his own financial resources. He arrived in Britain – according to another of his later recollections – with £400 and primarily receivables in Poland, where he was projecting a factory for G. Schwabe in Bielsko. He also noted that he had assets and receivables in Czechoslovakia, which he later estimated for the British bank at 1,663,000 crowns.

In one of his later letters, he clarified the matter regarding his financial situation at the time of his arrival in Britain more specifically: “When asked whether I would need financial support, I refused. At that time, I was receiving regular amounts from Poland, where I had built factories, which allowed me to live in England. In addition, I already had two major contracts: a plan for a margarine factory and to build ten warehouses for a shoemaking industrialist in London by the end of 1939.”

In the registration form dated June 23, 1939, Wiesner cited the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) as a reference in Britain and listed his language skills as German, Czech, and French. In the comments, he noted that “he intended to work in England” and that the Royal Institute of British Architects submitted an application on his behalf, specifically mentioning the names Mr. Jordan and Mr. Edward Carter.

The mentioned Edward Carter was born in 1902. He was an important figure in promoting modernism in Britain, becoming the librarian at RIBA in 1930 and later the secretary of the RIBA Refugee Committee, which provided assistance to architects fleeing from Nazi-occupied countries in Europe.

When asked in the form what his future plans were, Wiesner briefly replied: “To stay in the United Kingdom”

Wiesner also indicated several important dates in the document that allow for reconstructing his first weeks and months in exile. He stated, for example, that on June 14, 1939, he registered at the Bow Street police station in London, where he was assigned a registration certificate with number 736 790, allowing him to stay in Britain. In addition to Ernst Wiesner, his brother Erwin Wiesner also made it to Britain, for whom the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia assigned registration number 5972.

Wiesner also noted that he arrived in the British Isles on March 28, 1939, specifically in Croydon in South London. By the time he filled out the form for the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia, Wiesner had already been in Britain for three months.

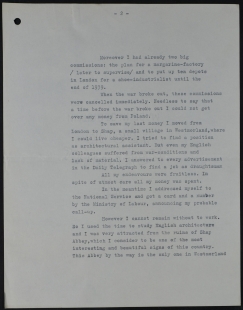

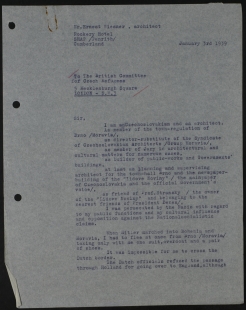

If Wiesner escaped from Brno on the day of the Nazi occupation, March 15, and arrived in London on March 28, then his journey to freedom lasted thirteen days. He described this dramatic journey in detail in a letter from January 3, 1940, to the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia with the following words: “When Hitler marched into Bohemia and Moravia, I had to flee from Brno immediately and took only one suit, a coat, and shoes with me. It was impossible for me to cross the Dutch border. Dutch officials refused passage through Holland to England. Before April 1, 1939, I was allowed as a Czechoslovak to cross the British borders without a visa. However, the Dutch officials said that I had overnight become a German citizen because Hitler – it was March 15 – had seized Czechoslovakia just a few hours earlier. Since I could not cross the Dutch border, I attempted to go to Belgium via Cologne and Aachen to get to England through Belgium.”

“Although I had a Belgian visa, Belgian border officials denied me passage. I had to return to Cologne. I hid in Cologne for two weeks. A foreigner, a Jew from Cologne, took me in, and I was allowed to stay for two weeks in his attic, which was terrible. After escaping several raids by foreigners, I attempted to walk from Aachen to Belgian territory two weeks later. After trying this three times unsuccessfully, one night in the rain and storm, I managed to cross the German border. However, I arrived in the Netherlands because I missed the route due to insufficient information. The Dutch officials sent me back to Germany, to the Gestapo. After a long process with the Gestapo about the purpose and destination of my journey, I told them that I was a former officer of the Austro-Hungarian army and gave them my word of honor that I had no money, luggage, or jewelry. I was then released.”

“I returned to Cologne, where I learned from my Dutch friends that I should try to cross the Belgian border another time. In case of being sent back again, I should contact the British Embassy in The Hague, which had been informed of the matter in the meantime. I tried again and succeeded.”

“Upon arriving in England, I approached the Royal Institute of British Architects /R.I.B.A./, which knew my name well from publications in English, American, and French magazines and based on my buildings in Czechoslovakia, which were visited by English architects in 1937. The Royal Institute (Mr. Jordan) offered to arrange my residence permit and work permit as an architect.”

After overcoming the challenging journey from Brno through Nazi Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium, Wiesner's first contact with exile can be considered relatively successful. Thanks to his European reputation and relationship with British architects, he obtained a work permit in Britain in August 1939 and was able to work as an architect there. He continued to receive financial income from the fees for building factories for G. Schwabe in Bielsko, and almost immediately received a commission in exile for the project and supervision of a margarine factory near Glasgow. Shortly thereafter, discussions also followed with the Czech shoemaking industrialist Baťa regarding a project for ten storage halls in London. The storage facilities for Baťa were to be built by the end of 1939.

The situation radically changed for Wiesner with the outbreak of World War II after September 1, 1939. Wiesner immediately lost his income from Poland, and the agreed contracts were also canceled.

Thus, from September 1939, Wiesner began to find himself in a very difficult economic situation. He decided to leave London and move to the countryside to, as he stated: “save the last of my money. London became too expensive. I wanted to try Edinburgh and Aberdeen (my Austrian friends live there) and find some work. I tried to find work in Kendal, Carlisle, and Penrith, towns in Westmorland and Cumberland. But very soon I realized the dire situation of all my English architect colleagues. All contracts are canceled, even for hospitals. I wrote to the Royal Institute of British Architects. They very much lamented it, but had no way to find a position or any work for me.”

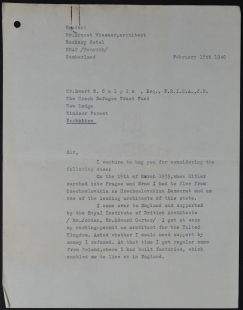

Similarly, he described this situation in a letter dated February 15, 1940, which he addressed to Ewart G. Culpin of the Czech Refugee Trust Fund: “To save my last money, I moved from London to Shap, a small village in Westmorland, where I could live more cheaply. I tried to find a position as an architectural assistant. I responded to every advertisement in the Daily Telegraph to find work as a draftsman. All my efforts were in vain. Despite my best care, all my money was spent.”

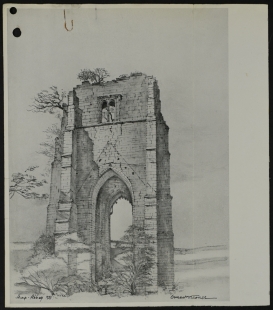

Wiesner thus left London and moved to the village of Shap in England, north of Leeds, where he lived at Rockery Hotel, Shap, Penrith, Cumberland. However, at that time he was out of any work and began to go into debt. Due to the lack of work and frustration, he undertook an interesting activity aimed at saving a local cultural monument. A few hundred meters from his new home were the remains of the Premonstratensian monastery from 1199, Shapp Abbey, which was dissolved in the 16th century and gradually fell into disrepair. Wiesner began to draw the fragments of the monastery and drew attention to its poor condition. He even launched a rescue operation aimed at its restoration.

“However, I cannot remain without work. I utilized this time to study English architecture and was very attracted to the ruins of Shap Abbey, which I consider one of the most interesting and beautiful features of this country. This abbey, by the way, is the only one in Westmorland and is in a state of disrepair, and every gust of wind could hasten its destruction. Therefore, I am trying to preserve this beautiful work of art.”

In another letter dated January 11, 1940, he described this effort: “I undertook this action with Shap Abbey because I find it unbearable not to be positive and active, and to appear here as an idle guest. Thus, of no use. Thanks to my attitude, I have also achieved intellectual success to a degree I never imagined: I have received recognition and interest from all sides. You see how the press follows my effectiveness and attributes it to Czechoslovak refugees. The Manchester Guardian now wants a study of the reconstruction of that building from me.”

Sometime soon after his arrival in the village of Shap, around the beginning of 1940, Wiesner's interest in the difficult situation focused on efforts to promote and restore the fragments of the Gothic monastery, which were also reported by the British press. The Gazette newspaper published an article on January 6, 1940, titled "URGENT NEED TO SAVE THE RUINS OF SHAP ABBEY" “The project to preserve the ruins of Shap Abbey, before they further deteriorate, was proposed by Mr. Ernest Wiesner, a Czechoslovak architect now living in Shap, who has gained significant support from various parts of Westmorland. Mr. Wiesner believes that this winter's storms may have such an impact on the already ominous cracks in the walls that if steps are not taken soon, the ancient monument may become irreparable. To raise funds, he had postcards and calendars printed from his own beautiful sketches for sale, and moreover, he voluntarily offered his architectural services if work were to begin.”

Wiesner indeed gained support for his activity from several local figures, but it is questionable how this effort to save the monastery developed further. Wiesner experienced, after the end of 1939 until the middle of 1940, probably the most challenging period, and in January 1940 he was forced to apply to the Czech Trust Fund for Refugees for financial support.

In a supplemental questionnaire dated February 10, 1940, for the Czech Trust Fund for Refugees, he answered the question of whether he had emigrated for racial or political reasons as follows: “From both a racial and political perspective as a democratic Czech and supporter of Beneš's party.” He further stated that he no longer had any financial resources and would like to obtain help in the form of a loan until he found employment.

The possibility of obtaining funds through the Czech Trust Fund, and applying for them, was likely prompted by Wiesner's friends. This is at least suggested by the way Wiesner himself requested aid, and also from a letter written by the former Austrian actress and emigrant Eva Schaffer.

On March 19, 1940, there was indeed internal communication within the Czech Trust Fund between Mrs. Lloyd and Mrs. Duncan-Jones, stating: “I received a letter from one of our refugees, Mrs. Eva Schaffer, about Mr. Wiesner. She writes: ‘My Czech friend, Mr. Ernest Wiesner, from Brno, a well-known architect who came to England shortly after March 15, 1939, also resides in Shap. He had to flee under very difficult and sad circumstances and was registered with the Czech Committee for Refugees, Mecklenburgh Square, in June 1939. He has never requested support. Now he is in a very, very desperate condition and is forced to incur debts.’

“Dr. Alfred Peres was so kind as to accept Mr. Ernest Wiesner's request for support to the Czech fund for refugees in Windsor. Mr. Wiesner, as far as I know, requested only a loan because he has a card from the Ministry of Labor, indicating that he is registered for National Service. Then Mr. Wiesner would like to repay the loan to the Czech Refugee Fund. This request was submitted on January 11, 1940, through Dr. Pres.”

I could clearly see how catastrophic a state Mr. Wiesner was living in; I ask you to consider his case and read his request from January 11, 1940.”

Following this internal communication within the Czech Trust Fund, they sent Wiesner a letter informing him of the approval of maintenance:

“Dear Mr. Wiesner,”

I am very sorry that your request for maintenance, submitted in January, has not yet been answered, but work in this office had been somewhat delayed due to illness.

We agree to provide you with maintenance, and I will send you a six-week allowance of £23 per week starting from early February.

I spoke with the head of the specialist department about job opportunities, and he thinks there is little chance of you finding work as an architect and believes your best chance would be as a drafting engineer. I would be pleased if you let me know if you already have any experience with this work or if you would like to retrain.”

Wiesner responded to this letter with gratitude:

“Dear Mrs. Duncan Jones,”

I received your letter dated March 13.

I can hardly express what I felt not only from the fact that you provided me with maintenance, which surely saved me from the worst, but also from how wonderfully it was offered.

Thank you very much.

Regarding your kind offer of a retraining course, I am very pleased with the opportunity offered.

The attached snippets of paper clearly show you what I am currently working on. I hope to complete this work with the help of H. M. Office of Works.

I would be very grateful to be able to complete this work.

With the help of the maintenance provided, I can continue my efforts to save this beautiful building from its destruction, which would be irreparable for English culture.

In any case, I will try to find work in my profession.

If that is not successful, I would appreciate a reminder of your kind offer of a retraining course.

With gratitude, Ernst Wiesner.”

In March 1940, Wiesner moved from his residence at Rockery Hotel in Shap to a new address, Shap South View Cottage, to be with Eva Schaffer. At the same time, Wiesner filled out another form for the Czech Trust Fund, in which he indicated, when asked if he wanted to emigrate further and, if so, where, “New Zealand and Canada.” It seems that compared to March 1939, when he arrived in Britain and stated he wanted to stay in Britain, his situation a year later was entirely different, and he was considering further emigration.

In addition to his effort to preserve the ruins of Shap Abbey, Wiesner, along with Eva Schaffer, organized several lectures on Czechoslovakia between February and May 1940. Eva Schaffer even established a Dramatic Society here, attempting to organize performances in Penrith and donate the proceeds to the British and Czech Red Cross. Wiesner informed the Czech Trust Fund about these activities:

“Dear Mrs. Duncan-Jones,”

I want to make my services available as soon as possible and would like to utilize them as much as I can. Even though I am over 50 years old, I do not think I am of no use in today's time… I am willing to undertake agricultural or forestry work or any administration according to my knowledge of Czech and German.

However, my only wish is to remain here and collaborate with Mrs. Eva Schaffer /reg. at the Czech Committee No. 391/, as I stay here in Shap with Mrs. Eva Schaffer. We have been friends for years. Moreover, Mrs. Schaffer has done secretarial and translation work for me.

Mrs. Eva Schaffer organizes lectures on Czechoslovakia throughout Westmorland to support the British and Czech Red Cross, for which I take care of the visual part. Perhaps there is an opportunity to provide these lectures in other parts of England to support the Red Cross. We cannot do much more in Westmorland.”

Given that the Czech Trust Fund is interested in forming groups for agricultural or forestry work, allow me to propose our cooperation with our best friends Mr. Erich Pohlmann and Mrs. Lotte Pohlmann, who now live here. Mr. and Mrs. Pohlmann, who belong to the Menne-Group, have been trying hard to become independent from the administration of the Czech Trust Fund and have managed to work as cooks in the Cornwall Hotel. Due to the growing aversion towards Germans and Austrians, they cannot find new positions, and I know they are in a desperate situation. Whether Mr. Erich Pohlmann enters the army or not, I feel we must take care of Mrs. Lotte Pohlmann, who is besides being a great cook, a skilled and modest worker.”

However, their activities did not meet with understanding at the Czech Trust Fund, and a few days later, Wiesner received the following response:

“Dear Mr. Wiesner,”

Thank you for your letter dated June 1. We would like to hear about the successful lectures you organized with Mrs. Schaffer to support the British and Czech Red Cross. However, it is currently not considered appropriate to continue these lectures. I have submitted both your names, as you requested, to the agricultural department for forestry work. They are likely to contact you soon.

As for Mr. and Mrs. Pohlmann, we have also heard from them, and we are considering their case.”

On the very day, both of them were indeed placed on the list of individuals designated for forestry work through internal communication.

Wiesner's difficult situation reached a climax by the fall of 1940. On July 26, 1940, he wrote the following:

“Dear Mrs. Duncan-Jones,”

fleeing from Czechoslovakia with one suit and one coat, I have no warm underwear or warm stockings or winter overalls. My hat is spoiled by the weather. Last winter was quite difficult. I am afraid my suit is quite worn and ragged.

Do you think it is possible to obtain a certain amount in addition to my weekly maintenance for the purchase of some things that I mostly need?

In the meantime, I have drawn six sketches of Westmorland, which I hope to sell in the near future for postcard printing. I hope to find companies that will be interested in purchasing these sketches. Once I manage to seal them, I will let you know how much I receive.

Additionally, I have produced a design for a coal-saving stove, which is twice as hot as an ordinary fireplace. Because I know how useful this could be for next winter, I am trying to contact a factory that would be interested in selling these easily assembled stoves.

I sincerely hope that I can succeed in becoming independent from the administration of the Committee.”

In November 1940, his maintenance was delayed, and Wiesner corresponded again with the Czech Trust Fund for Refugees in an effort to obtain his maintenance.

Moreover, in November 1940, Wiesner underwent two unpleasant police inspections, and there was a misunderstanding regarding the claim for maintenance. The Czech Trust Fund accused Wiesner of improperly appropriating maintenance for his brother Erwin. This matter personally affected Wiesner, and he responded as follows:

“As I mentioned in my letter of November 26 to Mrs. Lloyd, I had at that time two police inspections at South View Cottage. The police took all my documents and correspondence and kept them for more than 3 months. …

I am sure you will recognize that at this time, there may be ambiguities on both sides. There is no need to speak about forgery.

However, I fully understand your distrust. You certainly have your experiences. We are all strangers to you, and it is immensely difficult to distinguish between people.

From the very beginning, it has been difficult for me to be supported by the Trust Fund. You can trust me that I have done everything to achieve independence. All my efforts have been futile until recently. However, five weeks ago, the Cumberland and Westmorland County Council offered me a very good position. …

I hope I have clarified everything. Above all, I do not abuse your trust and kindness, which have saved me in times of trouble.”

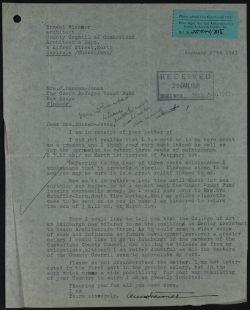

In early December 1940, Wiesner did indeed secure a job opportunity as an architectural assistant to the Cumberland County Council, with County architect John Haughan. On December 16, he was finally able to start work. The head constable of Westmorland and Cumberland, Philip T.B. Browne, was to help Wiesner, who drew the attention of the county council to him.

With the new job, Wiesner moved in December 1940 to the north, to the town of Carlisle, and lived at 4 Alfred Street North, Carlisle, Cumberland.

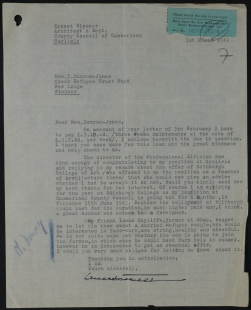

Sometime in January 1941, Wiesner received a job offer from the College of Art in Edinburgh, which offered him the position of senior assistant: “Since it would mean a wider range of work and influence on future developments, as well as a higher salary, I would like to go to Edinburgh if the members of the Cumberland County Council would be willing to release me from my commitments, although I doubt that as does everyone else. It seems that the county council members appreciate my work.”

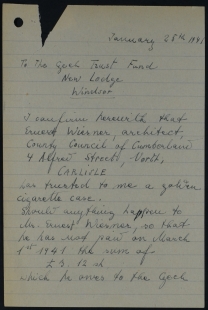

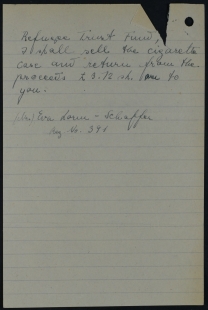

With the new employment, correspondence between the Czech Trust Fund for Refugees practically ended, and the archival file was thus exhausted. By March 1, 1941, Wiesner was to repay all his liabilities to the fund, for which he secured his gold cigarette case. On January 25, Eva Schaffer wrote: “I have been entrusted with the gold cigarette case. If anything happens to Mr. Ernst Wiesner, I am to pay the sum of £3 he owes to the Czech Refugee Fund by March 1, 1941.”

Wiesner worked at the county office in Cumberland until 1943, before moving back to London and starting to work for the Czechoslovak government in exile.

Michal Doležel

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.