LAGOS - CITY OF TOMORROW

|

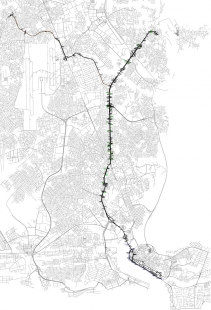

Lagos is a city of 13 million without a map, without a street network, without discernible urban planning. The only urban structure is embodied in the transport infrastructure of highways, corridors, and spaghetti junctions - complicated multi-level urban trajectories.

One street map can be obtained at the reception of the Sheraton Hotel, schematic and imprecise. Google Earth also does not display Lagos in any detailed manner, revealing only the clear outline of the city surrounded by the sea and an adjacent lagoon. A visitor thus arrives in the city without the opportunity to orient themselves in advance, to create a mental map of the place.

The absence of planned urbanism has resulted in the separation of transportation arteries and corridors (planned in the 1970s) from the physical city (a constantly changing organic structure). An example of "dematerialized" transport is the Third Mainland Bridge - an impressive engineering bridge structure physically detached from the land, located in the lagoon on stilts. The transport curve winding from north to south without connection to the structure and level of the city. The criterion for forming the curve is speed and the contour of Metropolitan Lagos - these are the determinants of form. The need for smooth transportation results in one of the most congested roads in the city, primarily due to the impossibility of diverging into the city's structure, turning off, or merging, thus dissipating.

|

The Lagos "network" serves as the megacity's lungs. They concentrate most of the energy fluctuating between weaker sections and energy-packed nodes. These nodes shift and change according to traffic conditions, time of day, day of the week, random events, violence, or traffic accidents. Variances in speeds, methods of overtaking and undercutting, directions of pedestrian paths characterize the microcosm of the city. The unexpected becomes commonplace.

The number of people whose livelihoods depend on transportation routes exceeds the number of motor vehicles. One cannot exist without the other. Transportation corridors concentrate Lagos's trading culture. The trading culture is based on a complicated hierarchy dependent on social status and gender. The result is various levels of commercial utilization of transportation routes - from "portable" trading dominated by young men, boys, children, to "static" shops along the roadway primarily operated by women, often settled on medians. Selling while caring for a baby tied to the chest or back is, as the hardest form of trade, the fate of many Lagos women. Breastfeeding and trading in the midst of a six-lane traffic artery go hand in hand. Trade in Lagos is overly dependent on the problematic traffic situation.

|

Danfos are a frequent and easy target for local gangs (Area boys) - youth mafia groups that control public transport in individual city areas. They do not allow competitors among themselves and do not like photographers. They are armed and often, in collaboration with drunk drivers, rob innocent passengers. A famous phrase they shout just before committing a robbery is: "One Chance." Danfos have the same nickname among Lagos residents.

This is transportation for the poorest, with no pre-established fare prices and no guarantee of delivery. Prices fluctuate depending on traffic peaks and demand. Traffic peaks surprisingly do not have regular intervals as in Europe but change continually, often illogically regarding passengers' daily directions (for example, traveling to the business center on Lagos Island in the morning and back in the evening is not a rule). Danfo fare prices can change and differ for the same distance by up to 100 percent. At the same time, this fascinating free market with prices allows transportation for the poorest residents - if they manage to negotiate a lower price.

|

Lagos public transport is a showcase of all that is worst. Safety is the main issue. Public transport forms a stark contrast to the individual transport of the city's wealthy inhabitants. The most common private car is the Toyota Avensis. Shiny expensive cars seem magically unscathed by the local transport reality - everything from Ferraris to Hummers reflects Nigeria's rediscovered wealth - black gold.

"Lagos is the city of tomorrow"....."We believe in Lagos" - these are a few phrases I hear from Makinde Ogunleye, the head of the Lagos Urban Development Department. In the city planning office, a shabby ground-floor building without air conditioning, where power frequently goes out and there are no computers, optimism prevails. The city is aware of its mega-problems and is beginning to address them (see the first attempts at model cities Ikeja, Apapa, Victoria Island in R. Koolhaas's book Content - published by Taschen), or at least pretends to solve them. Without air conditioning, progress is slow.

Political will is key for Lagos - "sincerity and purpose," says Mr. Ogunleye. Before the May state elections, there is a lot at stake, and the development afterward is uncertain.

There are said to be two urban studies: the Lagos Metropolitan Area Masterplan and the Lagos State Regional Plan. We were unable to obtain copies. Mr. Ogunleye lent his only copy to someone, and that person did not return it.

Lagos is a city of 13 million without a map, and it seems that it will remain so for some time.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

5 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

lagos/koolhaas

kruh

25.03.07 05:56

Film

Pavel Nasadil

26.03.07 02:10

otazka

ales sedivec

26.03.07 07:54

e-shop

Jan Kratochvíl

26.03.07 07:03

Film

Pavel Nasadil

27.03.07 08:30

show all comments