Toyo Ito and Mutsuro Sasaki - symbiosis of architecture and construction

It is not easy to write about other cultures. Especially for a Central European who would like to bring news of architectural events in faraway Japan. After all, there are equally interesting buildings or examples of cooperation between engineers and architects in our neighborhood. In the city above the Thames, names such as Cecil Balmond 1), Hanif Kara, or Jane Wernick are currently active. All of these engineers teach at prestigious architectural schools and participate in projects by world-renowned creators. Or one only needs to look into the rich European past and recall figures like Ove Arup 2), Peter Rice, or Edmond Happold.

It is natural for people to seek new possibilities and discover things that are still unknown. After a decade full of architectural excesses and extravagances, public attention is beginning to turn to Japanese skill in achieving impressive results with minimal means, which do not disturb and only slightly protrude from their surroundings. It is also interesting how people around the world strive to achieve the same results through different means. For example, the idea of geometric abstraction is understood linearly in the European context, while Japanese traditional notions of abstraction use curved shapes. Similarly, our understanding of symmetry contrasts with the Japanese asymmetrical aesthetics.3) These differing views demonstrate that there is more than one correct solution. Japanese culture is so distant from us that the solutions to similar problems will not differ in mere trifles.

Japanese cities appear to Europeans as undifferentiated, neutral, and constantly changing compact forms that can grow in any direction at any time without any restrictions. Due to frequent earthquakes, the Japanese culture lacks the idea of solid and massive architecture designed to endure as long as possible. Buildings are demolished and replaced with new forms and functions within short periods of just twenty years. Thus, Japanese cities change continuously without losing their basic concept: a neutral and fragmentary system with no reference points except for the communication and transportation system.4) Toyo Ito compares Tokyo to a system of microchips that only share intangible fluidity and the fact that it is created from many layers.5)

The work of Toyo Ito perhaps best captures the essence of Japanese cities based on a neutral underlying system to which any architectural work can be applied. Ito's denial of forms, vagueness, and transparency are much closer to the mentality of Japanese cities than the clearly defined and provocative buildings by Arata Isozaki or Tadao Ando. Kenneth Frampton wrote in the late 1970s that it would be mistaken to consider Ito a populist and that instead, we should appreciate the subtle sensitivity expressed in his works.6) Frampton's words still hold true today and may even be more relevant in current times.

Koji Taki, a Japanese philosopher and longtime friend of Ito, points out that Ito was one of the few architects capable of recognizing that architecture arises from societal experiences in connection with technology, and the architect is the person capable of translating these diverse elements into new spatial models.7) Taki further enumerates five chapters from Calvino's book American Lectures 8) (lightness, speed, precision, visibility, diversity) that strikingly resemble the concepts employed by Ito when describing his own architectural explorations.

The complexity of the contemporary Japanese world is perhaps best encapsulated in the joint work of architect Toyo Ito and his chief engineer Mutsuro Sasaki. The significance of this engineer is attested to by the publication and exhibition dedicated to him earlier this year at the prestigious London school Architectural Association. Toyo Ito even claims that his architectural thinking changed thanks to him.9) The approach to contemporary Japanese architecture surprisingly benefits most from the involvement of static engineer Matsuro Sasaki. A list of his collaborations features the most significant names from all three generations of architects: the representative of classic postmodernism Arata Isozaki, the most distinguished representative of contemporary Japanese architecture Toyo Ito, and from the emerging generation, Ryue Nishizawa.10)

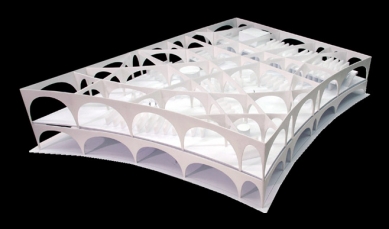

Many consider Toyo Ito to be the most innovative Japanese architect of today. His office, established as early as 1971, has come up with a whole range of interesting projects, but the media center in Sendai is considered a turning point in his career, for which Mutsuro Sasaki was invited due to the complexity of the construction. As initial inspiration, the architect used floating seaweed. When Sasaki received the first sketches of the competition proposal, he was impressed by the architect's vision but also worried about the unrealizability of the entire project. From a drawing where several asymmetrical tubes support thin ceiling panels, the engineer ultimately created thirteen unique grid structures of tubes supporting seven forty-centimeter square ceilings with a side of 50 meters. Never before had anything like this been realized. However, one could jokingly say that such performance from Sasaki is expected each time. Each of his designs is nothing short of a small engineering revolution. Sasaki replaces traditional empirical methods with new types of shape analyses utilizing principles of evolution and self-organization found in living beings. By employing the ESO computational method (advanced evolutionary structure optimization), the form is subsequently adjusted to create rational structural shapes 11). Through recurring nonlinear analyses, one begins to perceive the organic development of the construction form in its entire structure based on the relationship between its shape and automatic response. The resulting architecture dissolves and flows in the construction environment – it is a 'flowing structure'.12)

Two years ago, Akihisa Hirata wrote an article for the Japanese magazine a+u.13) In it, he described the way of working in Ito's studio, where he had the opportunity to spend several months as an intern. Ito had no trouble working simultaneously on two diametrically different projects. The Tokyo department store Tod's and the cultural forum in Ghent, Belgium, both utilized reinforced concrete as the main load-bearing structure, but while the first project worked with a linear motif of an abstracted crown of a tree transferred into the surface area of a load-bearing shell, the second design was formed by a complex spatial structure based on curves of several degrees and amorphous shapes.

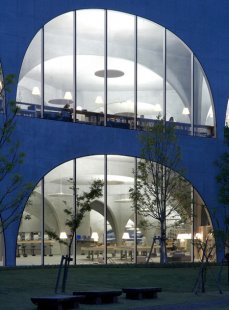

This article follows two current examples of buildings that emerged from the collaboration of architect Toyo Ito with engineer Mutsuro Sasaki. The bold concrete structures of the Tama university library and the crematorium in Kakamigahara were also developed in approximately the same period, and their authors chose the same material for the load-bearing structure, but again, these realizations differ greatly. This only confirms the words of Andrea Maffei that it is difficult to categorize Ito into any precise and firm stream of thought. His main intention is not to explore a single direction or create his own formal "style" that he would then use everywhere. His research begins with careful observation of the consumerist Japanese society and interpreting its social context.14)

Notes:

1) Extensive information about the court engineer of Rem Koolhaas can be found in Petr Šmídek: Cecil Balmond - beyond conventional engineering, Stavba 2/2007 p. 76-79

2) The story of a man who left behind an engineering empire with more than 9,000 employees can be found in Peter Jones: Ove Arup: Masterbuilder of Twentieth Century, Yale University Press, New Haven 2006

3) This difference is specifically described by the recently deceased Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa in his project for the extension of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where he reacted in his own language to G.T. Rietveld's modernist building.

4) Andrea Maffei: Toyo Ito, the Works, Electa, Milan 2001, p.9-18, ISBN 1-904313-01-9

5) Toyo Ito: Architecture in a Simulated City, Kenchiku Bunka, 12/1991

6) Kenneth Frampton: The New Wave of Japanese Architecture, Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, 1978

7) Koji Taki: Architecture is No Longer “Architecture“ in A. Maffei: T. Ito works, projects, writings, Milan 2001, p.19-25

8) Italo Calvino: American Lectures: Six Notes for the Next Millennium, Prostor 1999, ISBN 80-7260-006-0

9) “I realize that my architectural thinking changed immediately once we engaged you to work on Sendai.” T. Ito in: Mutsuro Sasaki: Morphogenesis of Flux Structure

10) Just last year, Sasaki has participated in these projects of SANAA: Novartis office building in Basel, glass pavilion for the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, or The New New Museum in New York, which will open on December 1, 2007.

11) Jeff M. Hammond: Mutsuro Sasaki: Flux Structure, Metropolis Tokyo, article 589

12) Mutsuro Sasaki: Morphogenesis of Flux Structure, AA, London 2006, ISBN 978-1-902902-57-9

13) Akihisa Hirata: Ghent and TOD’S: Coincidence of Opposites, a+u 417, 06/2005

14) Andrea Maffei: Toyo Ito, the Works, Electa, Milan 2001, p.9

It is natural for people to seek new possibilities and discover things that are still unknown. After a decade full of architectural excesses and extravagances, public attention is beginning to turn to Japanese skill in achieving impressive results with minimal means, which do not disturb and only slightly protrude from their surroundings. It is also interesting how people around the world strive to achieve the same results through different means. For example, the idea of geometric abstraction is understood linearly in the European context, while Japanese traditional notions of abstraction use curved shapes. Similarly, our understanding of symmetry contrasts with the Japanese asymmetrical aesthetics.3) These differing views demonstrate that there is more than one correct solution. Japanese culture is so distant from us that the solutions to similar problems will not differ in mere trifles.

Japanese cities appear to Europeans as undifferentiated, neutral, and constantly changing compact forms that can grow in any direction at any time without any restrictions. Due to frequent earthquakes, the Japanese culture lacks the idea of solid and massive architecture designed to endure as long as possible. Buildings are demolished and replaced with new forms and functions within short periods of just twenty years. Thus, Japanese cities change continuously without losing their basic concept: a neutral and fragmentary system with no reference points except for the communication and transportation system.4) Toyo Ito compares Tokyo to a system of microchips that only share intangible fluidity and the fact that it is created from many layers.5)

The work of Toyo Ito perhaps best captures the essence of Japanese cities based on a neutral underlying system to which any architectural work can be applied. Ito's denial of forms, vagueness, and transparency are much closer to the mentality of Japanese cities than the clearly defined and provocative buildings by Arata Isozaki or Tadao Ando. Kenneth Frampton wrote in the late 1970s that it would be mistaken to consider Ito a populist and that instead, we should appreciate the subtle sensitivity expressed in his works.6) Frampton's words still hold true today and may even be more relevant in current times.

Koji Taki, a Japanese philosopher and longtime friend of Ito, points out that Ito was one of the few architects capable of recognizing that architecture arises from societal experiences in connection with technology, and the architect is the person capable of translating these diverse elements into new spatial models.7) Taki further enumerates five chapters from Calvino's book American Lectures 8) (lightness, speed, precision, visibility, diversity) that strikingly resemble the concepts employed by Ito when describing his own architectural explorations.

The complexity of the contemporary Japanese world is perhaps best encapsulated in the joint work of architect Toyo Ito and his chief engineer Mutsuro Sasaki. The significance of this engineer is attested to by the publication and exhibition dedicated to him earlier this year at the prestigious London school Architectural Association. Toyo Ito even claims that his architectural thinking changed thanks to him.9) The approach to contemporary Japanese architecture surprisingly benefits most from the involvement of static engineer Matsuro Sasaki. A list of his collaborations features the most significant names from all three generations of architects: the representative of classic postmodernism Arata Isozaki, the most distinguished representative of contemporary Japanese architecture Toyo Ito, and from the emerging generation, Ryue Nishizawa.10)

Many consider Toyo Ito to be the most innovative Japanese architect of today. His office, established as early as 1971, has come up with a whole range of interesting projects, but the media center in Sendai is considered a turning point in his career, for which Mutsuro Sasaki was invited due to the complexity of the construction. As initial inspiration, the architect used floating seaweed. When Sasaki received the first sketches of the competition proposal, he was impressed by the architect's vision but also worried about the unrealizability of the entire project. From a drawing where several asymmetrical tubes support thin ceiling panels, the engineer ultimately created thirteen unique grid structures of tubes supporting seven forty-centimeter square ceilings with a side of 50 meters. Never before had anything like this been realized. However, one could jokingly say that such performance from Sasaki is expected each time. Each of his designs is nothing short of a small engineering revolution. Sasaki replaces traditional empirical methods with new types of shape analyses utilizing principles of evolution and self-organization found in living beings. By employing the ESO computational method (advanced evolutionary structure optimization), the form is subsequently adjusted to create rational structural shapes 11). Through recurring nonlinear analyses, one begins to perceive the organic development of the construction form in its entire structure based on the relationship between its shape and automatic response. The resulting architecture dissolves and flows in the construction environment – it is a 'flowing structure'.12)

Two years ago, Akihisa Hirata wrote an article for the Japanese magazine a+u.13) In it, he described the way of working in Ito's studio, where he had the opportunity to spend several months as an intern. Ito had no trouble working simultaneously on two diametrically different projects. The Tokyo department store Tod's and the cultural forum in Ghent, Belgium, both utilized reinforced concrete as the main load-bearing structure, but while the first project worked with a linear motif of an abstracted crown of a tree transferred into the surface area of a load-bearing shell, the second design was formed by a complex spatial structure based on curves of several degrees and amorphous shapes.

This article follows two current examples of buildings that emerged from the collaboration of architect Toyo Ito with engineer Mutsuro Sasaki. The bold concrete structures of the Tama university library and the crematorium in Kakamigahara were also developed in approximately the same period, and their authors chose the same material for the load-bearing structure, but again, these realizations differ greatly. This only confirms the words of Andrea Maffei that it is difficult to categorize Ito into any precise and firm stream of thought. His main intention is not to explore a single direction or create his own formal "style" that he would then use everywhere. His research begins with careful observation of the consumerist Japanese society and interpreting its social context.14)

Written for the magazine Beton 5/2007, p. 62-65

Notes:

1) Extensive information about the court engineer of Rem Koolhaas can be found in Petr Šmídek: Cecil Balmond - beyond conventional engineering, Stavba 2/2007 p. 76-79

2) The story of a man who left behind an engineering empire with more than 9,000 employees can be found in Peter Jones: Ove Arup: Masterbuilder of Twentieth Century, Yale University Press, New Haven 2006

3) This difference is specifically described by the recently deceased Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa in his project for the extension of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where he reacted in his own language to G.T. Rietveld's modernist building.

4) Andrea Maffei: Toyo Ito, the Works, Electa, Milan 2001, p.9-18, ISBN 1-904313-01-9

5) Toyo Ito: Architecture in a Simulated City, Kenchiku Bunka, 12/1991

6) Kenneth Frampton: The New Wave of Japanese Architecture, Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, 1978

7) Koji Taki: Architecture is No Longer “Architecture“ in A. Maffei: T. Ito works, projects, writings, Milan 2001, p.19-25

8) Italo Calvino: American Lectures: Six Notes for the Next Millennium, Prostor 1999, ISBN 80-7260-006-0

9) “I realize that my architectural thinking changed immediately once we engaged you to work on Sendai.” T. Ito in: Mutsuro Sasaki: Morphogenesis of Flux Structure

10) Just last year, Sasaki has participated in these projects of SANAA: Novartis office building in Basel, glass pavilion for the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, or The New New Museum in New York, which will open on December 1, 2007.

11) Jeff M. Hammond: Mutsuro Sasaki: Flux Structure, Metropolis Tokyo, article 589

12) Mutsuro Sasaki: Morphogenesis of Flux Structure, AA, London 2006, ISBN 978-1-902902-57-9

13) Akihisa Hirata: Ghent and TOD’S: Coincidence of Opposites, a+u 417, 06/2005

14) Andrea Maffei: Toyo Ito, the Works, Electa, Milan 2001, p.9

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment