Architect Jan Dvořák is an exemplary example

Miroslav Pavel

The three-part exhibition Unwanted Heritage. Architect Jan Dvořák (1925-1998) can be viewed until July 2nd at Špilberk Castle, Villa Tugendhat, and the cultural space PRAHA. The unifying theme is the life and work of architect Jan Dvořák, which is interpreted differently in each space, highlighting the complexity of our (non)acceptance of architecture that emerged in the socialist era. At first glance, the exhibition aligns with the numerous current activities fighting for the rights of "Socialist architecture," but it goes much further, eventually eluding them. The concept does not originate from the past, but from the present, which, after seeing the exhibition, does not seem much better or different than the era before the Velvet Revolution.

The impetus for creating the exhibition was the generous bequest of the architect's estate from his wife, Nina Dvořáková, to the Department of the History of Architecture of the City Museum of Brno. The challenging task of processing this extensive and largely unaddressed collection was undertaken by architecture historian Šárka Svobodová together with invited experts.

The core part of the trilogy Unwanted Heritage consists of the exhibition at Špilberk Castle, which is divided into eleven chapters. The first and largest surprise awaits in the antechamber, where a multimedia installation of Dvořák's unrealized design for the southern part of the Brno city center from 1993 is located. A three-dimensional color animation based on black-and-white drawings and sketches confidently frees the visitor from the expectations of a typical exhibition that pathetically looks back at the past. There seems to be no more lively topic in Brno than the South Center and the relocation of the main train station. The intertwining, sometimes romantically naive, visualizations offer a confrontation of his visions with the contemporary canon of architecture and urbanism. At the same time, they evoke urgent questions about what has changed in the 24 years since his proposals and how the city has progressed in the preparations for the revitalization of the area.

Entrance to the actual exhibition symbolically expresses our relationship with the cultural heritage of the socialist era. The floor is paved with drawings of Dvořák's works, covered by clear plexiglass. As a result, visitors have no choice but to trample and possibly dirty his legacy. Fortunately, it is protected by an almost invisible and fragile force. The curatorial selection of works was focused on exceptional pieces directly associated with the city of Brno or characteristic of Dvořák's work (Internát India, research institutes, Snaha, Hotel Myslivna, community centers, and typical details). Thanks to them, visitors can quickly form a framework understanding of the architect's artistic vocabulary, which is further examined in other parts of the exhibition. An engaging conclusion to this rapid introduction is a video montage featuring interviews with Dvořák's family and collaborators. The expectedly positive, albeit sometimes bitterly realistic, testimonies from the wife and colleagues conclude with a sincere conversation with the son, who, as the only non-professional witness, debates the dogmatic protection of not only his father's but generally socialist architectural monuments. He is the voice of the lay public, which still hesitates over their qualities and their right to exist.

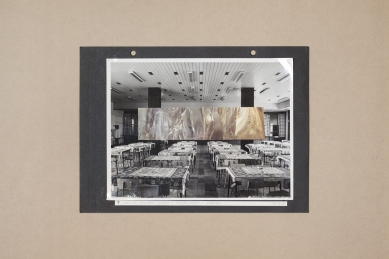

Jan Dvořák was not only an architect but also a sculptor, and with his designs (as he had to, given the requirements of the time), he collaborated with several artists of his choosing. These aspects are primarily addressed in two exhibitions. The cultural house in Práče presents the first of them. Dvořák first used the concept of a cantilevered folded reinforced concrete roof, which he repeated in other cultural houses with minor changes and adjustments to the floor plan. This showcase of projects highlights not only the architect's unique, almost sculptural handwriting but also the hardships of socialist construction, where every project was limited by the supplies and offers available in the then-construction market. His distinctive authorship was thus something exceptional, or at least it was almost a superhuman task. Dvořák's designs navigated this environment deftly and managed to extract the maximum from limited possibilities. However, he was not alone. A high degree of diplomacy toward the regime and innovation had to be demonstrated by all architects who did not want to remain trapped in the claws of Stavoprojekt and national planning. The limited production of the time is also referenced by the exhibition creators themselves, who placed the second exhibition, focusing on the artistic component of Dvořák's portfolio, on mass-produced kitchen countertops. The intimidating structure of the panels carries the visualization of the artistic decoration of the Dukovany Nuclear Power Plant and Internát India, which have practically not survived to this day. The installation clearly contrasts mass production with unique artistic elements, these two components, which formed inseparable parts of construction during socialism. It was left to the architect to find the balance between them and the highest possible aesthetic sense. It remains a question of how well they succeeded and to what extent people became accustomed to these elements. Just as over time, you will appreciate the playful and creative nature of the panel installation, so too have mass-produced products simply become witnesses of the time and icons of the then-production.

The change in aesthetic values after the Velvet Revolution is evident in the next part of the exhibition, which delves deeply into the current state of Dvořák's works. The striking large-format photograph of the Research Institute of Rolling Bearings in Brno-Komárov captures the deplorable condition of the building, which is literally covered with advertisements from the roof to the entrance lobby and has undergone numerous nonsystematic and non-authorial modifications. By being isolated from the local context and positioned in the gallery spaces, its despair and degradation are further highlighted. Even the most beautiful and quality project loses its identity in the battle with the commercial element. This is not solely a weakness of socialist architecture; it is just subjected to it more often, as it is supposedly ugly by nature. However, its enhancement need not be a priori malicious intent. This is also demonstrated by the video installation about the Funeral Ceremony Hall in Vrbno pod Pradědem. This project was halted during construction due to the change in the political regime. It was completed only in 2013, but without the author's contribution and without referring to the original documentation. The completion, financed by the city, was carried out in the spirit of DIY and folk taste. Thus, there are exactly two components that in the socialist era replaced the lack of anything beautiful and distinctive. In this case, however, they were brought about by good intentions and contempt for the role of the architect. It should be emphasized that the exhibition itself does not evaluate this process but merely provides testimony. Similarly, in the case of the video interview with architect Martin Rudiš, whose studio replaced the Snaha building on Lidická Street in Brno with their residence Lužánky. Although his studio sought to preserve the original building, Snaha had to yield to new urban functions and aesthetic demands.

The conclusion of the exhibition at Špilberk Castle features a video about Hotel Myslivna. At first glance, it presents a relaxed and pleasant probe into the current state of this once-prominent hotel. Numerous original elements mix with modern interventions, yet it still does not lose its identity. The sobering realization comes when the viewer understands that what is being presented is in fact a silent epitaph. The hotel is likely to face the same fate as the Karlovy Vary Thermal Hotel, the station in Havířov, and Bystřice pod Hostýnem, and when it is at its worst, similarly to the now dying Transgas or the vanished Hotel Praha.

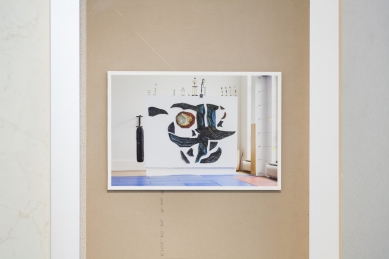

The second part of the exhibition Unwanted Heritage in the cultural space PRAHA transfers the theme of socialist planning and production into the present day. Students from the Faculty of Architecture at VUT in Brno, David Helešic and Marek Svoboda, studied the principles and logic of the mechanism of European funds and subsidies in the Czech Republic. Based on their findings, they predicted the requirements of municipalities and chose one of them for their experiment. They utilized Dvořák's concept of a cantilevered folded reinforced concrete roof of cultural houses as a standardized element, and with its help, they designed a new sports hall. The result, besides the exhibition itself, is the success of a project that may indeed be realized. A project based on principles we reject, but it was simply necessary to translate it into the current language for us to understand it.

The final, third part of the exhibition titled Replication is located in the spaces of Villa Tugendhat. The location was not chosen randomly. Architect Jan Dvořák was one of the active initiators of the repair and protection of this now national cultural monument. The modest exhibition in the villa's basement maps Dvořák's dedication and the complicated behind-the-scenes of the restoration. Unfortunately, this part of the exhibition trilogy is the weakest. Not in content, but in formal aspects, where even interesting photographs, plans, and sketches are not sufficiently self-sufficient for the viewer to reinterpret them without assistance and any description. However, if the viewer takes the effort to read the quality accompanying brochure, they might find their way through the exhibition.

The three-part exhibition Unwanted Heritage. Architect Jan Dvořák (1925-1998) is a comprehensive excursion into the past and a sincere examination of the present. Its author, Šárka Svobodová, managed to find a neutral position while providing a lively and accessible format that offers ample arguments for forming one's own opinion. It is a very challenging task to draw conclusions about an entire era of socialist architecture based on one example. However, architect Jan Dvořák serves as a good and exemplary example in the then vocabulary. His work certainly lacks artistic quality and does not belong to the ordinary average. However, he is not its ultimate representative either. Dvořák was a capable architect who tried to extract the maximum from what was available. Just as an architect today navigates between the investor, the client, the contractor, and legislative restrictions. However, this is not about legitimizing a monstrous regime or searching for its positives. It is about looking at architecture itself, which is merely an innocent witness of the time. An innocent yet significantly important one. It cannot defend itself; it can only tell about our past and remind us of true values.

Miroslav Pavel

Institute of Theory and History of Architecture FA CTU

The impetus for creating the exhibition was the generous bequest of the architect's estate from his wife, Nina Dvořáková, to the Department of the History of Architecture of the City Museum of Brno. The challenging task of processing this extensive and largely unaddressed collection was undertaken by architecture historian Šárka Svobodová together with invited experts.

The core part of the trilogy Unwanted Heritage consists of the exhibition at Špilberk Castle, which is divided into eleven chapters. The first and largest surprise awaits in the antechamber, where a multimedia installation of Dvořák's unrealized design for the southern part of the Brno city center from 1993 is located. A three-dimensional color animation based on black-and-white drawings and sketches confidently frees the visitor from the expectations of a typical exhibition that pathetically looks back at the past. There seems to be no more lively topic in Brno than the South Center and the relocation of the main train station. The intertwining, sometimes romantically naive, visualizations offer a confrontation of his visions with the contemporary canon of architecture and urbanism. At the same time, they evoke urgent questions about what has changed in the 24 years since his proposals and how the city has progressed in the preparations for the revitalization of the area.

Entrance to the actual exhibition symbolically expresses our relationship with the cultural heritage of the socialist era. The floor is paved with drawings of Dvořák's works, covered by clear plexiglass. As a result, visitors have no choice but to trample and possibly dirty his legacy. Fortunately, it is protected by an almost invisible and fragile force. The curatorial selection of works was focused on exceptional pieces directly associated with the city of Brno or characteristic of Dvořák's work (Internát India, research institutes, Snaha, Hotel Myslivna, community centers, and typical details). Thanks to them, visitors can quickly form a framework understanding of the architect's artistic vocabulary, which is further examined in other parts of the exhibition. An engaging conclusion to this rapid introduction is a video montage featuring interviews with Dvořák's family and collaborators. The expectedly positive, albeit sometimes bitterly realistic, testimonies from the wife and colleagues conclude with a sincere conversation with the son, who, as the only non-professional witness, debates the dogmatic protection of not only his father's but generally socialist architectural monuments. He is the voice of the lay public, which still hesitates over their qualities and their right to exist.

Jan Dvořák was not only an architect but also a sculptor, and with his designs (as he had to, given the requirements of the time), he collaborated with several artists of his choosing. These aspects are primarily addressed in two exhibitions. The cultural house in Práče presents the first of them. Dvořák first used the concept of a cantilevered folded reinforced concrete roof, which he repeated in other cultural houses with minor changes and adjustments to the floor plan. This showcase of projects highlights not only the architect's unique, almost sculptural handwriting but also the hardships of socialist construction, where every project was limited by the supplies and offers available in the then-construction market. His distinctive authorship was thus something exceptional, or at least it was almost a superhuman task. Dvořák's designs navigated this environment deftly and managed to extract the maximum from limited possibilities. However, he was not alone. A high degree of diplomacy toward the regime and innovation had to be demonstrated by all architects who did not want to remain trapped in the claws of Stavoprojekt and national planning. The limited production of the time is also referenced by the exhibition creators themselves, who placed the second exhibition, focusing on the artistic component of Dvořák's portfolio, on mass-produced kitchen countertops. The intimidating structure of the panels carries the visualization of the artistic decoration of the Dukovany Nuclear Power Plant and Internát India, which have practically not survived to this day. The installation clearly contrasts mass production with unique artistic elements, these two components, which formed inseparable parts of construction during socialism. It was left to the architect to find the balance between them and the highest possible aesthetic sense. It remains a question of how well they succeeded and to what extent people became accustomed to these elements. Just as over time, you will appreciate the playful and creative nature of the panel installation, so too have mass-produced products simply become witnesses of the time and icons of the then-production.

The change in aesthetic values after the Velvet Revolution is evident in the next part of the exhibition, which delves deeply into the current state of Dvořák's works. The striking large-format photograph of the Research Institute of Rolling Bearings in Brno-Komárov captures the deplorable condition of the building, which is literally covered with advertisements from the roof to the entrance lobby and has undergone numerous nonsystematic and non-authorial modifications. By being isolated from the local context and positioned in the gallery spaces, its despair and degradation are further highlighted. Even the most beautiful and quality project loses its identity in the battle with the commercial element. This is not solely a weakness of socialist architecture; it is just subjected to it more often, as it is supposedly ugly by nature. However, its enhancement need not be a priori malicious intent. This is also demonstrated by the video installation about the Funeral Ceremony Hall in Vrbno pod Pradědem. This project was halted during construction due to the change in the political regime. It was completed only in 2013, but without the author's contribution and without referring to the original documentation. The completion, financed by the city, was carried out in the spirit of DIY and folk taste. Thus, there are exactly two components that in the socialist era replaced the lack of anything beautiful and distinctive. In this case, however, they were brought about by good intentions and contempt for the role of the architect. It should be emphasized that the exhibition itself does not evaluate this process but merely provides testimony. Similarly, in the case of the video interview with architect Martin Rudiš, whose studio replaced the Snaha building on Lidická Street in Brno with their residence Lužánky. Although his studio sought to preserve the original building, Snaha had to yield to new urban functions and aesthetic demands.

The conclusion of the exhibition at Špilberk Castle features a video about Hotel Myslivna. At first glance, it presents a relaxed and pleasant probe into the current state of this once-prominent hotel. Numerous original elements mix with modern interventions, yet it still does not lose its identity. The sobering realization comes when the viewer understands that what is being presented is in fact a silent epitaph. The hotel is likely to face the same fate as the Karlovy Vary Thermal Hotel, the station in Havířov, and Bystřice pod Hostýnem, and when it is at its worst, similarly to the now dying Transgas or the vanished Hotel Praha.

The second part of the exhibition Unwanted Heritage in the cultural space PRAHA transfers the theme of socialist planning and production into the present day. Students from the Faculty of Architecture at VUT in Brno, David Helešic and Marek Svoboda, studied the principles and logic of the mechanism of European funds and subsidies in the Czech Republic. Based on their findings, they predicted the requirements of municipalities and chose one of them for their experiment. They utilized Dvořák's concept of a cantilevered folded reinforced concrete roof of cultural houses as a standardized element, and with its help, they designed a new sports hall. The result, besides the exhibition itself, is the success of a project that may indeed be realized. A project based on principles we reject, but it was simply necessary to translate it into the current language for us to understand it.

The final, third part of the exhibition titled Replication is located in the spaces of Villa Tugendhat. The location was not chosen randomly. Architect Jan Dvořák was one of the active initiators of the repair and protection of this now national cultural monument. The modest exhibition in the villa's basement maps Dvořák's dedication and the complicated behind-the-scenes of the restoration. Unfortunately, this part of the exhibition trilogy is the weakest. Not in content, but in formal aspects, where even interesting photographs, plans, and sketches are not sufficiently self-sufficient for the viewer to reinterpret them without assistance and any description. However, if the viewer takes the effort to read the quality accompanying brochure, they might find their way through the exhibition.

The three-part exhibition Unwanted Heritage. Architect Jan Dvořák (1925-1998) is a comprehensive excursion into the past and a sincere examination of the present. Its author, Šárka Svobodová, managed to find a neutral position while providing a lively and accessible format that offers ample arguments for forming one's own opinion. It is a very challenging task to draw conclusions about an entire era of socialist architecture based on one example. However, architect Jan Dvořák serves as a good and exemplary example in the then vocabulary. His work certainly lacks artistic quality and does not belong to the ordinary average. However, he is not its ultimate representative either. Dvořák was a capable architect who tried to extract the maximum from what was available. Just as an architect today navigates between the investor, the client, the contractor, and legislative restrictions. However, this is not about legitimizing a monstrous regime or searching for its positives. It is about looking at architecture itself, which is merely an innocent witness of the time. An innocent yet significantly important one. It cannot defend itself; it can only tell about our past and remind us of true values.

Miroslav Pavel

Institute of Theory and History of Architecture FA CTU

This article is supported by the SGS CTU grant SGS15/220/OHK1/3T/15 (The Formation of Modern Architecture by Public Interest and Changing Lifestyles, researcher Miroslav Pavel)

photo: Zdeněk Porcal (Studio Flusser) | www.studioflusser.com

photo: Zdeněk Porcal (Studio Flusser) | www.studioflusser.com

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment