The exhibition will take visitors through the vanished world of Brno cafes

|

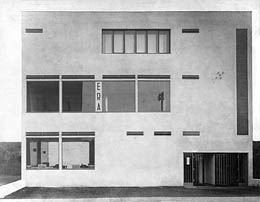

| Café Era in Černá Pole |

According to some sources, the coffee house tradition in Brno is several years older than in Prague. "The first café is said to have been established in the city as early as 1702 by a Turk named Achmet," said historian of Czech hospitality Karel Altman. It is said that the Viennese archbishop interceded for the Turk when granting the license. Cafés quickly multiplied, reaching their golden age in the late 19th century and during the First Republic. After the war and due to nationalization, many establishments disappeared, while others completely changed their purpose. More cafés ceased operations following privatizations in the 1990s, regrets museum director Pavel Ciprian.

The exhibition is not organized chronologically but by the locations where cafés were established. The first cafés grew in the historical city center, at Zelny trh (Vegetable Market), on Orlí Street, and around Jakubské Square. Another section is dedicated to parks and streets that urban planners created around the center after the city walls were demolished. The original Zeman café was located there, a landmark functionalist building in Brno that later had to give way to the construction of Janáček Theatre, and now a replica stands a bit further away. The last section captures cafés in the expanding bourgeois districts around the center of Brno.

The atmosphere in the cafés is suggested to visitors through reproductions of old postcards and photographs, accompanying texts, and other exhibits – tables, chairs, mannequins, printed materials, or coffee machines. Images primarily feature establishments that no longer exist. For example, the Savoy, which could seat up to a thousand visitors at once, the café of the Zemský House and Hotel Padowetz, or the famous Toman Café, located where Czech Street intersects with Freedom Square.

Altman recalls that in the past, people sought various types of cafés. Some were connected with restaurants, others with pastry shops and billiard halls. A special group consisted of night cafés, which replaced today's bars. While in the 19th century cafés were predominantly patronized by the social elite, after World War I, they also served the rising middle class. "Cafés on Czech and German corners also had different atmospheres," noted curator Lenka Kudělková.

The exhibition at Špilberk will run until April 20.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment