Conversation with Buchner Bründler Architects

Source

Ing. arch. Karolína Kripnerová

Ing. arch. Karolína Kripnerová

Publisher

Petr Šmídek

23.02.2019 10:00

Petr Šmídek

23.02.2019 10:00

Czech Republic

České Budějovice

Daniel Buchner

Andreas Bründler

Buchner Bründler Architekten

On the occasion of the opening of the exhibition Constellations - Correlations at the House of Art in České Budějovice, we had the opportunity to ask a few questions to the main representatives of the Swiss studio Buchner Bründler on February 14, 2019. The interview with Andreas Bründler and Daniel Buchner for archiweb.cz was conducted by Karolína Kripnerová. During the half-hour debate, the discussion touched on the status of architecture in Swiss society, their relationship with previous masters, and construction opportunities in a city shaped by H&deM.

Your way of thinking about architecture seems close to Aldo Rossi, who viewed the city as a guardian of the past and the memory of humanity. On the other hand, the direction of your dialogue with the environment is quite radical and experimental. How do you combine these two tendencies in your buildings?

Our approach is based on the history of the office, where for the first five years we focused mainly on smaller private projects. These building tasks required us to focus more on the specific design than on the urban context. Most of the time, these were houses on the outskirts of cities or in rural settings. Of course, the context is important, but in these projects, it was not the main focus; it served more as a backdrop. Thus, we asked ourselves, what can be designed on a specific site? How can we read and understand the place?

The works created by Aldo Rossi are still present in Switzerland and have certainly influenced us, although we are not a generation directly after him. However, the architecture we create is not dictated by Rossi's theory. We do not feel that we should create the city with another "clean cut." On the contrary, designing for us means the possibility of creating architectural impulses. We see the city in a broader context than just the classical linear – let’s say Rossi's style. Nevertheless, context is essential for us, and we work with it, as can be seen here at the exhibition. The exhibited objects have, in fact, been decontextualized and placed in a new environment, which allowed for the emergence of new relationships.

Among other things, you are also the authors of the reconstruction of the St. Alban hostel in Basel, where quality architecture and design are made accessible to people with otherwise limited incomes. Is this a general trend in Switzerland to make quality architecture widely available?

Yes, that is an absolute necessity! Quality does not mean that it is expensive; quality means being aware of values and architectural themes. The St. Alban hostel is a building with a long history. It was built around 1860 as a textile manufactory and was a modern building for its time: it had a clear, clean structure with a linear light guide. In the 1980s, it was converted into a hostel. We created a third layer of the project, which developed the previous two. A fundamental aspect for us was the new orientation of the building so that it became accessible not only from the back but also from the street side, which is oriented towards the Rhine and the city. Thus, we gave the building a new face. Of course, the financial resources were limited, but that was actually an advantage: we had to concentrate on what was essential. I think we succeeded very well, also because we architects had the project completely under control.

In Switzerland, the architect traditionally plays a key role, leading the project, having it under control, and also being responsible for it. In this project, the central role of the architect was successful, thanks to dialogue with the client and their trust in us. Respect for traditions, which is prevalent in Swiss society, is also important. Projects begin with a competition, where we carefully familiarize ourselves with the history of the building, define what the object needs, and also what challenges and opportunities the reconstruction presents. It is a very intensive process. In this case, the entire project lasted about three years.

At the turn of the millennium, theorists introduced the term Swissbox, to which Swiss architects immediately objected, but the generation of that time was indeed united by simple forms, which were later abandoned, although the emphasis on material and craftsmanship remained. Can you clarify, from an internal perspective, what the essence of Swiss architecture is?

I probably won’t tell you any definition of Swiss architecture, but there are certain processes typical of Switzerland that lead to the creation of architecture. I can say that over the last century, a culture has developed in which important buildings are built by architects, and that is embedded in the consciousness of the population, as is the importance of architecture.

One important tool has become competitions. In the case of public contracts, significant people are included in the dialogue and decision-making. And this process of competition guarantees that we achieve quality and the best solution.

This is also related to the fact that Switzerland is a very densely populated country. Yes, we have completely uninhabited mountains, but outside of them, human activity is evident everywhere; it is an urban landscape. When I traveled by train from Prague to České Budějovice, I saw almost only forests and nature – that is unimaginable in Switzerland! There is almost no place left without traces of settlement. And what does that mean? With what we have left, we must handle it with the utmost caution. We are aware of the scarcity of resources and the value of what remains and what we have at our disposal.

And for that reason, important societal discourse arises: what can we do with it? What should we design and build?

And the second aspect is the role of the architect, who traditionally has the role of project leader. They control all processes, including the budget, leading to the realization of the building. They are in close contact with suppliers and the investor, selecting and deciding in a way that achieves quality. This also creates a high awareness of quality.

What is your relationship with the Swiss-born one of the greatest architects of the past century, Le Corbusier?

I would say he is as present as Aldo Rossi. Perhaps even more so. The themes he dealt with—free facade or fluid floor plan, and other modernist ideas—also appear in our projects.

Equally important are materials in Le Corbusier's work, primarily concrete, and plasticity – the sculptural quality of the works. He transforms simple construction means that are normally used only purposefully, achieving high quality with them.

And what do we dislike about him? Apart from the Weber Gallery in Zurich, we admire everything! I must say that unfortunately, I haven’t seen many of his works. However, they are certainly monuments in the history of architecture. Even though most of it is communicated through books, unless you go to India, Chandigarh, studying his projects develops you and brings you new ideas.

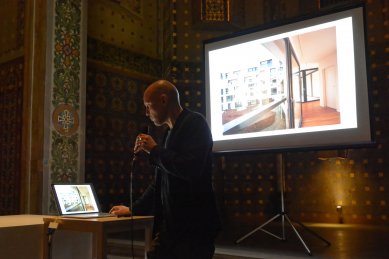

Your lecture in Prague last year was titled Mutations. The current exhibition in České Budějovice is titled Constellations - Correlations. In what sense do you choose these words?

It is teamwork based on discussion. We brought together ideas for this space, worked with the documentation, and with the place itself. Here it is a white box, a neutral space for art. We decided to focus solely on the two-dimensional medium – photography. These "grow" from the ground, are connected to the earth and wall, thus creating a new space. We did not want to do a didactic presentation: four or five rooms mean four or five projects; on the contrary, we worked with surprise and developed the fact that architecture displayed in the gallery is decontextualized. By mixing projects and surprising installations, new relationships emerged, new perspectives, new correlations between projects, and new insights. Developing a specific theme is our way of working.

During your visit to Prague last year, you had at least a partial opportunity to familiarize yourself with contemporary Czech architecture. Have any Czech names or buildings remained in your memories?

Yes, one building stuck with me, it was fantastic! It is the extension of the opera from the 1970s; I unfortunately don't remember the author's name (New Stage of the National Theatre, note by the editor). It is a building completely made of glass. The extension creates a pleasant, quiet square and leads to an interesting dialogue with the neoclassical opera building. I read about it – I realize that the project must have been controversial, but I find it amazing.

I had seen cubists before, but the precise work of Plečnik at the Castle was new to me. There is much more, but those names! For instance, the hexagonal shopping center (OD Kotva, note by the editor), that was exciting!

This is probably a frequently asked question and too personal, so we ask it almost at the end of our interview.

What does sustainability mean to you?

For us, it means creating buildings that remain interesting and durable even after their initial phase of use. And therefore, it is important for us to maintain high quality; that is the guarantee of longevity. It is also important for us to be aware that not everything needs to be necessarily new, but we should carefully consider what might still serve or simply needs to be restored. There is a lot of discussion about various parameters, and also about the energy aspect of the design. We have an ambivalent attitude toward that; we believe that an emphasis on technology diverts attention from architectural themes. And I think this needs correction so that the discussion can return to the essential topics of architecture.

Our approach is based on the history of the office, where for the first five years we focused mainly on smaller private projects. These building tasks required us to focus more on the specific design than on the urban context. Most of the time, these were houses on the outskirts of cities or in rural settings. Of course, the context is important, but in these projects, it was not the main focus; it served more as a backdrop. Thus, we asked ourselves, what can be designed on a specific site? How can we read and understand the place?

The works created by Aldo Rossi are still present in Switzerland and have certainly influenced us, although we are not a generation directly after him. However, the architecture we create is not dictated by Rossi's theory. We do not feel that we should create the city with another "clean cut." On the contrary, designing for us means the possibility of creating architectural impulses. We see the city in a broader context than just the classical linear – let’s say Rossi's style. Nevertheless, context is essential for us, and we work with it, as can be seen here at the exhibition. The exhibited objects have, in fact, been decontextualized and placed in a new environment, which allowed for the emergence of new relationships.

Among other things, you are also the authors of the reconstruction of the St. Alban hostel in Basel, where quality architecture and design are made accessible to people with otherwise limited incomes. Is this a general trend in Switzerland to make quality architecture widely available?

Yes, that is an absolute necessity! Quality does not mean that it is expensive; quality means being aware of values and architectural themes. The St. Alban hostel is a building with a long history. It was built around 1860 as a textile manufactory and was a modern building for its time: it had a clear, clean structure with a linear light guide. In the 1980s, it was converted into a hostel. We created a third layer of the project, which developed the previous two. A fundamental aspect for us was the new orientation of the building so that it became accessible not only from the back but also from the street side, which is oriented towards the Rhine and the city. Thus, we gave the building a new face. Of course, the financial resources were limited, but that was actually an advantage: we had to concentrate on what was essential. I think we succeeded very well, also because we architects had the project completely under control.

In Switzerland, the architect traditionally plays a key role, leading the project, having it under control, and also being responsible for it. In this project, the central role of the architect was successful, thanks to dialogue with the client and their trust in us. Respect for traditions, which is prevalent in Swiss society, is also important. Projects begin with a competition, where we carefully familiarize ourselves with the history of the building, define what the object needs, and also what challenges and opportunities the reconstruction presents. It is a very intensive process. In this case, the entire project lasted about three years.

At the turn of the millennium, theorists introduced the term Swissbox, to which Swiss architects immediately objected, but the generation of that time was indeed united by simple forms, which were later abandoned, although the emphasis on material and craftsmanship remained. Can you clarify, from an internal perspective, what the essence of Swiss architecture is?

I probably won’t tell you any definition of Swiss architecture, but there are certain processes typical of Switzerland that lead to the creation of architecture. I can say that over the last century, a culture has developed in which important buildings are built by architects, and that is embedded in the consciousness of the population, as is the importance of architecture.

One important tool has become competitions. In the case of public contracts, significant people are included in the dialogue and decision-making. And this process of competition guarantees that we achieve quality and the best solution.

This is also related to the fact that Switzerland is a very densely populated country. Yes, we have completely uninhabited mountains, but outside of them, human activity is evident everywhere; it is an urban landscape. When I traveled by train from Prague to České Budějovice, I saw almost only forests and nature – that is unimaginable in Switzerland! There is almost no place left without traces of settlement. And what does that mean? With what we have left, we must handle it with the utmost caution. We are aware of the scarcity of resources and the value of what remains and what we have at our disposal.

And for that reason, important societal discourse arises: what can we do with it? What should we design and build?

And the second aspect is the role of the architect, who traditionally has the role of project leader. They control all processes, including the budget, leading to the realization of the building. They are in close contact with suppliers and the investor, selecting and deciding in a way that achieves quality. This also creates a high awareness of quality.

What is your relationship with the Swiss-born one of the greatest architects of the past century, Le Corbusier?

I would say he is as present as Aldo Rossi. Perhaps even more so. The themes he dealt with—free facade or fluid floor plan, and other modernist ideas—also appear in our projects.

Equally important are materials in Le Corbusier's work, primarily concrete, and plasticity – the sculptural quality of the works. He transforms simple construction means that are normally used only purposefully, achieving high quality with them.

And what do we dislike about him? Apart from the Weber Gallery in Zurich, we admire everything! I must say that unfortunately, I haven’t seen many of his works. However, they are certainly monuments in the history of architecture. Even though most of it is communicated through books, unless you go to India, Chandigarh, studying his projects develops you and brings you new ideas.

Your lecture in Prague last year was titled Mutations. The current exhibition in České Budějovice is titled Constellations - Correlations. In what sense do you choose these words?

It is teamwork based on discussion. We brought together ideas for this space, worked with the documentation, and with the place itself. Here it is a white box, a neutral space for art. We decided to focus solely on the two-dimensional medium – photography. These "grow" from the ground, are connected to the earth and wall, thus creating a new space. We did not want to do a didactic presentation: four or five rooms mean four or five projects; on the contrary, we worked with surprise and developed the fact that architecture displayed in the gallery is decontextualized. By mixing projects and surprising installations, new relationships emerged, new perspectives, new correlations between projects, and new insights. Developing a specific theme is our way of working.

During your visit to Prague last year, you had at least a partial opportunity to familiarize yourself with contemporary Czech architecture. Have any Czech names or buildings remained in your memories?

Yes, one building stuck with me, it was fantastic! It is the extension of the opera from the 1970s; I unfortunately don't remember the author's name (New Stage of the National Theatre, note by the editor). It is a building completely made of glass. The extension creates a pleasant, quiet square and leads to an interesting dialogue with the neoclassical opera building. I read about it – I realize that the project must have been controversial, but I find it amazing.

I had seen cubists before, but the precise work of Plečnik at the Castle was new to me. There is much more, but those names! For instance, the hexagonal shopping center (OD Kotva, note by the editor), that was exciting!

This is probably a frequently asked question and too personal, so we ask it almost at the end of our interview.

What does sustainability mean to you?

For us, it means creating buildings that remain interesting and durable even after their initial phase of use. And therefore, it is important for us to maintain high quality; that is the guarantee of longevity. It is also important for us to be aware that not everything needs to be necessarily new, but we should carefully consider what might still serve or simply needs to be restored. There is a lot of discussion about various parameters, and also about the energy aspect of the design. We have an ambivalent attitude toward that; we believe that an emphasis on technology diverts attention from architectural themes. And I think this needs correction so that the discussion can return to the essential topics of architecture.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment