Public Space in the Era of Real Capitalism

Interview with Terezie Nekvindová and Pavel Karous

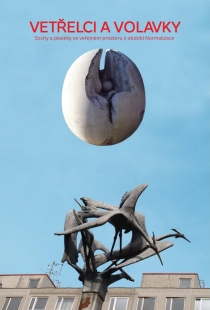

Artworks intended for the decoration of architecture or public spaces have existed since antiquity. In Czechoslovakia, during the existence of the socialist state, this production was supported by law; a certain percentage of the building's budget had to go towards the creation of a work of art. During the "golden sixties," many quality works were created. During the normalization period, this practice continued, mostly through the realizations of official authors who had a better chance of securing financially rewarding work. However, less prominent authors also obtained commissions, sneakily incorporating themes from their free creation into them. This led to the creation of many quality realizations, especially in newly established housing estates and around public buildings. Since 1989, there has been a systematic destruction of these works, due to vandalism and the trade in precious metals, but also because of the society's and politicians' indifference to public space. This has resulted in irreversible losses that are not adequately replaced by newly emerging art. One of the initiatives that documents, popularizes, and aims to protect realizations from the 70s and 80s of the 20th century is the project Aliens and Herons by Pavel Karous, with whom we present an interview.

Your project Aliens and Herons aims to document, popularize, and protect sculptures in public space from the normalization era. When and why did you start it?

Four years ago I started photographing sculptures that interested me and creating an archive from them. I approached the work more seriously two years ago. With the creation of a website and filming a documentary for Czech Television, we can now speak of a project. I am a sculptor, so naturally, I am interested in sculptures, additionally, I am attracted to the aesthetic outputs of dictatorship. Everyone knows Soviet avant-garde, Italian futurism, but few realize that in the Czech Republic we have the aesthetic output of another dictatorship right under our noses. More than the 50s, I enjoy the normalization period; it is not so clear-cut, we cannot easily differentiate between good and bad. The spectrum is much wider, and some individuals oscillate from one end to the other. Naturally, I come from the generation of Husák's children, so for me, it is also a way of understanding my parents' lives and a certain nostalgia for childhood.

Is the term dictatorship too strong for the normalization?

The project is defined by the years 1968 and 1989, thus roughly by the arrival and withdrawal of Soviet troops and the change in cultural policy related to these changes. The country was occupied, which is a certain manifestation of dictatorship.

How do you define the official art of that time for yourself?

An artist working on a commission for architecture is dependent on financial support and always has to adapt to the client a bit. Since antiquity, public sculpture has expressed the idea of its time, just like architecture. In the 50s, soldiers and collective farmers were created, whereas in normalization, there are minimum such plastics. Only the top officials shared lucrative commissions for Lenins and Gottwalds among themselves. Otherwise, it's a flood of tired modernity that can express socialist ideals but does not depict overtly political themes. Figurative creation predominates with themes of work, sport, family, and romantic life, or there are abstract decorative works inspired by flora, fauna, or modern technology. The authors, in the vast majority, resisted the imprecisely defined socialist realism.

The project title comes from the typology you created based on the study of public sculpture. How did you categorize these sculptures?

I approach sculptures like a mushroom picker; I collect them and categorize them by species. During normalization, there was only one client, the officially controlled Union of Czech Fine Artists. That's why these works are often similar. It’s like there’s only one advertising agency in capitalism. Artists constantly adapted to the same taste, which was often reactionary. The commissioners who decided on the selections were mostly a generation older than the authors. Thus, things can easily be categorized, or they can be created according to morphologies of various columns. This is pleasant for the “collector.” We named the species based on folk sayings. When someone photographs or films sculptures in housing estates, locals become curious. They may ask in surprise: “Are you photographing those cocoons?” If people give familiar names to objects, even derogatory ones, it proves that they function in public space. It can be a landmark, a meeting place, and at the same time, it contributes to the genius loci. We collect these “urban legends” when mapping plastics. For instance, Lost the Keys, those are the melancholic girls in a squat, or Hip Bones of Mammoths, those are concrete or asbestos-cement climbing structures for children made by modernist sculptors when they wanted to express complete abstraction. These sculptures made of convex and concave shapes are undoubtedly inspired by the English sculptor Henry Moore, who in turn drew inspiration from bones and sea debris. His inspiration thus circles back in the intuitively chosen name. Triffids, those sculptures are named after the sci-fi Day of the Triffids, which was published here in 1972. The book is about mutated carnivorous plants bullying the remnants of a blinded population. We use this name for the Brussels vertical fountains inspired by flora, which are topped with chalices.

Are they, for example, the kinetic plastics of Jiří Novák?

Yes, Novák is a typical “triffidist.” He himself loved sci-fi, so that inspiration may not be coincidental. The last are Aliens and Herons. The name for Aliens came from the sci-fi film Alien from 1979 and denotes egg-shaped forms influenced mainly by Constantin Brancusi. For example, works by Eva Kmentová, but the main breeding grounds of Aliens were the studios of František Pacík, Jaroslav Vacek, and Milan Vácha. These eggs were the best way to preserve the abstraction of the 60s while also meeting the assignment—idea of new life, spring, etc. It can be slightly justified that the socialist idea is contained in the sculpture while one can carve out the ideal shape.

And what about Herons?

The obsession with placing herons in housing estates began with Vincenc Vingler when he made an abstract sculpture of a water bird for the fountain of our pavilion at Expo 58. The fountain naturally implies a water surface, which calls for a water bird. You avoid the human figure, and thus also any connections with socialist realism, while simultaneously fulfilling the requirement for descriptiveness. Moreover, birds with their aerodynamics and elegance are a very appealing theme for sculptors. Thus arose a flood of flamingos and herons before every elementary school or kindergarten. Unfortunately, due to a complete lack of interest from responsible authorities, these sculptures are disappearing; due to their subtle execution, they are easily theft-prone: a flamingo stands on one leg, so it can easily be twisted off. Until recently, densely populated herons have disappeared in twenty years. After the revolution, no one pressured the raw material collection points, so most of these sculptures are now melted down.

You refer to the sculptures in architecture as ambiguously “4% art,” why?

The building law then required all state construction projects to allocate 1–4% of the construction budget for artistic solutions. The four percent art was mildly pejorative at that time. Sculptors outside of the official sphere mocked these commissions; at least that's how Čestmír Suška from the Stubborn Ones remembers normalization, even though he also occasionally got similar jobs.

In some countries where there was no socialism, the connection between art and architecture was also legally supported. Today, the need for state intervention is reassessed; there is debate whether it should be done or not.

Chicago had a similar law, which was not state but municipal. Within that framework, alongside a flood of average commercial plastics, there were also works by minimalists. In every era, 99% of things are produced that are a product of their time and do not survive the time of their creation. However, if support is lacking, none will be produced. After the 90s and 2000s, almost nothing will remain in Prague except for Anna Chromy's work at the Estates Theatre or Ley Vivot's at Senovážné Square. These underperforming but productive sculptors usually offer their works to the municipality for free. Officials choose the sculptures, not urban planners, architects, artists, or curators. It is thus decided by people with legal or economic education; it's like if I were to decide about Prague's water management. The decoration of cities with artworks is a tradition since antiquity. To think that the free hand of the capital market and maximum land exploitation will solve something for us is nonsense. No private investor is interested in the visual functionality of public space. Investment goes into interior design because it makes money, but public space has no support.

What is the situation like in Western Europe?

I don’t follow it in detail, but it surely cannot be worse than here. The period from 1968–1989 and from 1989 until now are temporally two identical periods. During normalization, there were hundreds of realizations compared to the period after. And a certain percentage of them are objectively quality works. I am, of course, a madman, so I like everything, but the works of Karel Malich, Stanislav Kolíbal, Eva Kmentová, Jiří Novák, Hugo Demartini, Kurt Gebauer, or even the generation of Stubborn Ones from the late 80s have universally defendable value. When these two two-decade periods are one day assessed—only in a narrow perspective of visual art in public space, our era of "real capitalism" has dramatically lost.

It seems that today the only bright exception is Liberec thanks to the initiative of Ivona Raimannová.

Fortunately, there are swallows here. The civic association Spacium, which Ivona Raimannová leads, has been successfully placing contemporary sculptures in the public space of Liberec for several years, which is surprising because Liberec otherwise manifests as a very uncultured, corrupt city dominated by the Syner company, where quality architecture is being demolished. But in this regard, it manages to create an exposition of contemporary art in Liberec. People encounter art naturally without having to step into a stone gallery. In Brno, the director of the House of Arts, Rostislav Koryčánek, organizes Sculptures in the Streets, some realizations remain in the city permanently. This year’s edition was curated by Karel Císař, who proclaims radical conceptual creation, which demonstrates the progressiveness and courage of the organizer. Another good example is Litomyšl, where the public space is excellently managed. An example can be the outdoor exhibition by Aleš Veselý from two years ago, where in collaboration with Josef Pleskot he filled the entire city with his monumental sculptures. The association Za Opavu is also active. Thanks to them, we can today admire the works of Kurt Gebauer or František Skála in the city. Conversely, the situation in Prague is discouraging—except for the great Memento mori by Krištof Kintera, installed under the Nuselský Bridge a month ago. However, this realization was tolerated rather than supported by the city district.

Are you working on your project alone?

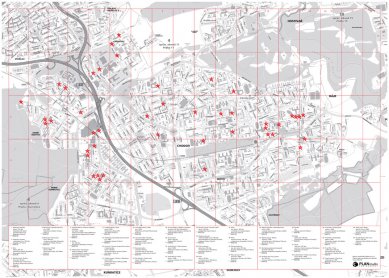

So far, I have done everything myself, out of enthusiasm and with minimal financial support. Recently, together with two friends, we established a civic association. Historian Veronika Dospělová will take care of the art historical work: archives, retrieval, verification, etc. Then I sought an architect or urban planner and a lawyer who specializes in copyright law—that is the only legally enforceable protection. Marek Dolejš ideally combines both. We are not aiming for a museum to be created here. The city must evolve, but every time public space is revitalized, it should be done better than what it replaces. To relocate a plastic and replace it with a parking lot or other commercial use is not an improvement of public space for me, but its colonization by capitalism.

How are you doing with the specific protection of individual sculptures?

So far, there have been a few such cases. We were almost the happiest when we managed to save the sculpture Dálky by Jiří Novák in the Novodvorská parterre through a petition campaign and media coverage. The Prague 4 district did not account for this exceptional realization from the end of the 60s during its revitalization, and thanks to this activity, we managed to reverse this decision. We were supported by the National Heritage Institute, the Architects' Club, the management of the AAAD, AVU, etc. Everyone agreed that the sculpture made for the excellent housing estate by Aleš Bořkovec and Vladimír Ježek belongs in that place, and if it were placed in a repository, it would lose its function. The sculptor collaborated closely with the architects at the time of creation, so it fits ideally in proportions. I would like Prague 4 to reconsider the urbanism around it, attempt to remove the nonsensical pitched roofs on panel buildings and the insulation, and return the gray color scheme. It would be good to realize that a third of the population in the Czech Republic lives in housing estates, and thus places where public space has succeeded should not be overlooked. Jiří Novák, a pioneer of kinetic sculpture in our country, unfortunately did not live to see the outcome of the fight to preserve his work. He was not on friendly terms with communism; therefore he did not have many realizations, and in the last ten years, about three of his realizations were removed in Prague 4, which is painful to watch for a man over eighty who knows he will not create new plastics—not only because of his age but also due to the current lack of opportunities.

Many contemporary artists work with the aesthetics of the 70s and 80s. Why is this period interesting to you?

I studied under Marián Karl, who belongs generationally to this time. Our generation is influenced by people who grew up on minimalism and non-constructivist tendencies. In my free work, I address the relationship between geometry and human society; I am attracted to the aesthetics of dictatorship; I draw inspiration from utilitarian architecture, the design of transport, agricultural, or military machines. Geometry is a language in which society can be described. Normalization is extremely visually interesting for my generation, which attended elementary school during the revolution. The buildings were gray, thus sculpture-like. The visual results of early capitalism, where houses are covered with advertisements, glitter, or styrofoam facades in ice cream colors, must irritate any sensitive aesthetician. We are reaping the fruits of normalization today. In normalization, even the most humble combine harvester had strong aesthetic qualities as it still stemmed from the 60s and the First Republic. Every milk packaging looked like a primitively understood Bauhaus motif. I understand that people who suffered in some way during the regime associate this aesthetic with a period of adversity, but we have the right to view this era from a bird's-eye perspective and say that the work with the visual aspect was interesting and of quality.

However, you refer to the plastics you watch as normalization plastics, which is rather a political designation.

I do not perceive normalization solely in connection with politics; I regard it as a designation of a certain stage. Karel Gott is a pop singer, but he can also be normalization. When someone makes a comic about the heydrichiada, they cannot avoid the swastika, but that does not mean they are a fascist. When I defend a work in the office from destruction, I am usually hit in the face with whether I am a communist. I was born in 1979 and did not even attend the Pioneer. I would like to ask that person in return what they did before 1989. My project is non-political.

In what way is your project artistic?

In addition to mapping sculptures, we do projects that we call Strassenkunst. We intervene in sculptures with temporary actions to draw attention to them. For instance, there was an action for the New Stage of the National Theatre, where we temporarily interfered with the sculpture The Birth of Culture by Josef Malejovský from 1982 for about three months. When we photographed the sculpture, the skateboarders who rode around there said to us: “Oh, you are photographing chewing gum?” And indeed, that sculpture looks like chewing gum as if Otto Gutfreund had inhaled toluene for twenty years. So I wrapped the sculpture in pink glue and modeled it into the shape of a giant piece of chewing gum. After all, chewing gum stuck to the sidewalk is also a symbol of public space for me. Or in Folimanka, based on “revitalization,” the plastics of Bohumil Zemánek and Jaroslav Hladký were removed. The municipality was not able to say why this happened and where the sculptures are today, even though millions were spent on revitalization. So we enlarged photos of those sculptures to their original size, glued them on particleboard, and cut out their silhouettes. We then placed these props back at their original locations. Hladký had Prkýnkář from 1982 here, possibly the first skateboard sculpture in the world. It was a very refined piece, a figure with a helmet, pads, and a skateboard; it looked very robotic and futuristic, the base of the sculpture was a U-ramp. Bohumil Zemánek, who made sculptures of fat bureaucrats and was persecuted by the regime for it, here had a humorous group of children who whistle at each other and flirt together. I remember that sculpture as a small child; we climbed on it, and the children had the same proportions as us. It was my first encounter with sculpture, and probably not just for me. I lament that such a sculpture disappears during the revitalization for which there are funds. The remaining sculpture, Gymnast by Václav Frydecký, avoided this madness, so we created, with the author's consent, a protective plexiglass bumper zone for it for three months.

Are you planning to expand your interest outside of Prague, potentially to other periods or other artistic genres?

No, not directly, but any enthusiast who comes across aliens or herons in their town can submit it themselves through a form in our database. We are not the only ones; for instance, some city districts in Prague also monitor sculptures in their territory; Prague 11 has a great database, for example.

Your site is also in English; have you received any feedback from abroad? Do you collaborate with similar projects elsewhere?

Last year, Stephan Strsembski, a curator from Bonn, included me in an exhibition about altruism, where he presented Czech art created out of joy and enthusiasm. Thanks to that, a few people from Germany reached out to me. Americans also contact me because it is something unusual, even strange for them. I regret that I do not have contact with anyone from the former Soviet satellite states. I know that there is a project in Poland that focuses on herons, but it is not solely focused on sculptures.

Are you already functioning as an “institution”? Can anyone turn to you if a sculpture is at risk?

Unintentionally, I am starting to change into an activist, but that is not close to me. I am better at making mischief than officially communicating with authorities. But it’s great that people turn to me. I can help draft a petition, mention it in the media.

What sort of misconduct is happening right now?

There are plenty of such occurrences, for instance, when they removed an eight-meter Brussels relief Nature and Creation by Jaroslav Vacek from the Plamínková Elementary School in Prague 4 in the course of insulating the building by progressively cutting it and dropping it from a height to the ground. As a mockery, they painted a basketball on the façade and claimed it was a full-fledged replacement. Another conceptual removal in Prague 4 occurred at another elementary school, where about a nine-meter relief by Zdeněk Šimek met its demise. It is terrifying to me that the project is signed by an architect who has an education from ČVUT and he doesn’t even understand the quality of execution. I could go on for a long time—removals of Hugo Demartini, Jiří Novák, and Karel Bečvář in the Barrandov housing estate, etc. There are hundreds of such cases in Prague! The justification is often that it is “communist junk,” but then it turns out that the owners are rather lazy to maintain the sculptures and do not bother to find out what kind of sculpture it is. Citizens of Ústí nad Labem are currently fighting for the preservation of the sculpture Labe by Karel Kronych, which stands in front of a department store by Růžena Žertová. The sculpture corresponds with the façade of the building, but the owner of the department store wants to remove it for the sake of garages. Nowadays, there is no money for new realizations; there was back then. The owner does not realize that he is discarding something that will attract tourists in twenty years. Baroque sculptures were also created in a time that is very controversial; according to Jirásek, it was a time of darkness. Those sculptures were ideological tools, symbols of violent re-Catholicization, yet no one doubts that they belong in today's cities.

So, is insulation currently the biggest problem for reliefs?

It is primarily poor revitalization of housing architecture. The culprits are therefore not only thieves of precious metals and hooligans. The main problem is vulgar commercialization of public space, which is facilitated by corruption, and a crucial role is played by insufficient vision in the field of urbanism. Thus, some officials participate in the devaluation of public space hand in hand with vandals.

Don’t some sculptures also end up in the gardens of private individuals?

I hope that is the case, that somewhere at Orlík all those destroyed Malichs, Sýkoras, etc. are. On the other hand, I am afraid that someone might really start speculating with this cultural heritage. But I know for sure that most of the works ended up under jackhammers, often they were not even portable. For example, in Suchdol, there was a monumental five-meter realization by Karel Malich. At a time when his pastels are being bought for hundreds of thousands in private collections, his giant sculpture, which everyone could come and see, is being destroyed.

Shouldn’t the argumentation then change and speak primarily about the financial value of these plastics?

But this is public space, where everything serves everyone; no one has an interest in that...

Pavel Karous (*1979) graduated from the AAAD in Prague, where he currently works as an assistant professor at Rony Plesl's Glass Studio. He initiated the project Aliens and Herons, which aims to document, protect, and popularize sculptures in public space from the 70s and 80s of the 20th century.

More information at www.vetrelciavolavky.cz and www.pavelkarous.cz.

Film by Rozálie Kohoutová (2008) for Czech Television - here.

Four years ago I started photographing sculptures that interested me and creating an archive from them. I approached the work more seriously two years ago. With the creation of a website and filming a documentary for Czech Television, we can now speak of a project. I am a sculptor, so naturally, I am interested in sculptures, additionally, I am attracted to the aesthetic outputs of dictatorship. Everyone knows Soviet avant-garde, Italian futurism, but few realize that in the Czech Republic we have the aesthetic output of another dictatorship right under our noses. More than the 50s, I enjoy the normalization period; it is not so clear-cut, we cannot easily differentiate between good and bad. The spectrum is much wider, and some individuals oscillate from one end to the other. Naturally, I come from the generation of Husák's children, so for me, it is also a way of understanding my parents' lives and a certain nostalgia for childhood.

Is the term dictatorship too strong for the normalization?

The project is defined by the years 1968 and 1989, thus roughly by the arrival and withdrawal of Soviet troops and the change in cultural policy related to these changes. The country was occupied, which is a certain manifestation of dictatorship.

How do you define the official art of that time for yourself?

An artist working on a commission for architecture is dependent on financial support and always has to adapt to the client a bit. Since antiquity, public sculpture has expressed the idea of its time, just like architecture. In the 50s, soldiers and collective farmers were created, whereas in normalization, there are minimum such plastics. Only the top officials shared lucrative commissions for Lenins and Gottwalds among themselves. Otherwise, it's a flood of tired modernity that can express socialist ideals but does not depict overtly political themes. Figurative creation predominates with themes of work, sport, family, and romantic life, or there are abstract decorative works inspired by flora, fauna, or modern technology. The authors, in the vast majority, resisted the imprecisely defined socialist realism.

The project title comes from the typology you created based on the study of public sculpture. How did you categorize these sculptures?

I approach sculptures like a mushroom picker; I collect them and categorize them by species. During normalization, there was only one client, the officially controlled Union of Czech Fine Artists. That's why these works are often similar. It’s like there’s only one advertising agency in capitalism. Artists constantly adapted to the same taste, which was often reactionary. The commissioners who decided on the selections were mostly a generation older than the authors. Thus, things can easily be categorized, or they can be created according to morphologies of various columns. This is pleasant for the “collector.” We named the species based on folk sayings. When someone photographs or films sculptures in housing estates, locals become curious. They may ask in surprise: “Are you photographing those cocoons?” If people give familiar names to objects, even derogatory ones, it proves that they function in public space. It can be a landmark, a meeting place, and at the same time, it contributes to the genius loci. We collect these “urban legends” when mapping plastics. For instance, Lost the Keys, those are the melancholic girls in a squat, or Hip Bones of Mammoths, those are concrete or asbestos-cement climbing structures for children made by modernist sculptors when they wanted to express complete abstraction. These sculptures made of convex and concave shapes are undoubtedly inspired by the English sculptor Henry Moore, who in turn drew inspiration from bones and sea debris. His inspiration thus circles back in the intuitively chosen name. Triffids, those sculptures are named after the sci-fi Day of the Triffids, which was published here in 1972. The book is about mutated carnivorous plants bullying the remnants of a blinded population. We use this name for the Brussels vertical fountains inspired by flora, which are topped with chalices.

Are they, for example, the kinetic plastics of Jiří Novák?

Yes, Novák is a typical “triffidist.” He himself loved sci-fi, so that inspiration may not be coincidental. The last are Aliens and Herons. The name for Aliens came from the sci-fi film Alien from 1979 and denotes egg-shaped forms influenced mainly by Constantin Brancusi. For example, works by Eva Kmentová, but the main breeding grounds of Aliens were the studios of František Pacík, Jaroslav Vacek, and Milan Vácha. These eggs were the best way to preserve the abstraction of the 60s while also meeting the assignment—idea of new life, spring, etc. It can be slightly justified that the socialist idea is contained in the sculpture while one can carve out the ideal shape.

And what about Herons?

The obsession with placing herons in housing estates began with Vincenc Vingler when he made an abstract sculpture of a water bird for the fountain of our pavilion at Expo 58. The fountain naturally implies a water surface, which calls for a water bird. You avoid the human figure, and thus also any connections with socialist realism, while simultaneously fulfilling the requirement for descriptiveness. Moreover, birds with their aerodynamics and elegance are a very appealing theme for sculptors. Thus arose a flood of flamingos and herons before every elementary school or kindergarten. Unfortunately, due to a complete lack of interest from responsible authorities, these sculptures are disappearing; due to their subtle execution, they are easily theft-prone: a flamingo stands on one leg, so it can easily be twisted off. Until recently, densely populated herons have disappeared in twenty years. After the revolution, no one pressured the raw material collection points, so most of these sculptures are now melted down.

You refer to the sculptures in architecture as ambiguously “4% art,” why?

The building law then required all state construction projects to allocate 1–4% of the construction budget for artistic solutions. The four percent art was mildly pejorative at that time. Sculptors outside of the official sphere mocked these commissions; at least that's how Čestmír Suška from the Stubborn Ones remembers normalization, even though he also occasionally got similar jobs.

In some countries where there was no socialism, the connection between art and architecture was also legally supported. Today, the need for state intervention is reassessed; there is debate whether it should be done or not.

Chicago had a similar law, which was not state but municipal. Within that framework, alongside a flood of average commercial plastics, there were also works by minimalists. In every era, 99% of things are produced that are a product of their time and do not survive the time of their creation. However, if support is lacking, none will be produced. After the 90s and 2000s, almost nothing will remain in Prague except for Anna Chromy's work at the Estates Theatre or Ley Vivot's at Senovážné Square. These underperforming but productive sculptors usually offer their works to the municipality for free. Officials choose the sculptures, not urban planners, architects, artists, or curators. It is thus decided by people with legal or economic education; it's like if I were to decide about Prague's water management. The decoration of cities with artworks is a tradition since antiquity. To think that the free hand of the capital market and maximum land exploitation will solve something for us is nonsense. No private investor is interested in the visual functionality of public space. Investment goes into interior design because it makes money, but public space has no support.

What is the situation like in Western Europe?

I don’t follow it in detail, but it surely cannot be worse than here. The period from 1968–1989 and from 1989 until now are temporally two identical periods. During normalization, there were hundreds of realizations compared to the period after. And a certain percentage of them are objectively quality works. I am, of course, a madman, so I like everything, but the works of Karel Malich, Stanislav Kolíbal, Eva Kmentová, Jiří Novák, Hugo Demartini, Kurt Gebauer, or even the generation of Stubborn Ones from the late 80s have universally defendable value. When these two two-decade periods are one day assessed—only in a narrow perspective of visual art in public space, our era of "real capitalism" has dramatically lost.

It seems that today the only bright exception is Liberec thanks to the initiative of Ivona Raimannová.

Fortunately, there are swallows here. The civic association Spacium, which Ivona Raimannová leads, has been successfully placing contemporary sculptures in the public space of Liberec for several years, which is surprising because Liberec otherwise manifests as a very uncultured, corrupt city dominated by the Syner company, where quality architecture is being demolished. But in this regard, it manages to create an exposition of contemporary art in Liberec. People encounter art naturally without having to step into a stone gallery. In Brno, the director of the House of Arts, Rostislav Koryčánek, organizes Sculptures in the Streets, some realizations remain in the city permanently. This year’s edition was curated by Karel Císař, who proclaims radical conceptual creation, which demonstrates the progressiveness and courage of the organizer. Another good example is Litomyšl, where the public space is excellently managed. An example can be the outdoor exhibition by Aleš Veselý from two years ago, where in collaboration with Josef Pleskot he filled the entire city with his monumental sculptures. The association Za Opavu is also active. Thanks to them, we can today admire the works of Kurt Gebauer or František Skála in the city. Conversely, the situation in Prague is discouraging—except for the great Memento mori by Krištof Kintera, installed under the Nuselský Bridge a month ago. However, this realization was tolerated rather than supported by the city district.

Are you working on your project alone?

So far, I have done everything myself, out of enthusiasm and with minimal financial support. Recently, together with two friends, we established a civic association. Historian Veronika Dospělová will take care of the art historical work: archives, retrieval, verification, etc. Then I sought an architect or urban planner and a lawyer who specializes in copyright law—that is the only legally enforceable protection. Marek Dolejš ideally combines both. We are not aiming for a museum to be created here. The city must evolve, but every time public space is revitalized, it should be done better than what it replaces. To relocate a plastic and replace it with a parking lot or other commercial use is not an improvement of public space for me, but its colonization by capitalism.

How are you doing with the specific protection of individual sculptures?

So far, there have been a few such cases. We were almost the happiest when we managed to save the sculpture Dálky by Jiří Novák in the Novodvorská parterre through a petition campaign and media coverage. The Prague 4 district did not account for this exceptional realization from the end of the 60s during its revitalization, and thanks to this activity, we managed to reverse this decision. We were supported by the National Heritage Institute, the Architects' Club, the management of the AAAD, AVU, etc. Everyone agreed that the sculpture made for the excellent housing estate by Aleš Bořkovec and Vladimír Ježek belongs in that place, and if it were placed in a repository, it would lose its function. The sculptor collaborated closely with the architects at the time of creation, so it fits ideally in proportions. I would like Prague 4 to reconsider the urbanism around it, attempt to remove the nonsensical pitched roofs on panel buildings and the insulation, and return the gray color scheme. It would be good to realize that a third of the population in the Czech Republic lives in housing estates, and thus places where public space has succeeded should not be overlooked. Jiří Novák, a pioneer of kinetic sculpture in our country, unfortunately did not live to see the outcome of the fight to preserve his work. He was not on friendly terms with communism; therefore he did not have many realizations, and in the last ten years, about three of his realizations were removed in Prague 4, which is painful to watch for a man over eighty who knows he will not create new plastics—not only because of his age but also due to the current lack of opportunities.

Many contemporary artists work with the aesthetics of the 70s and 80s. Why is this period interesting to you?

I studied under Marián Karl, who belongs generationally to this time. Our generation is influenced by people who grew up on minimalism and non-constructivist tendencies. In my free work, I address the relationship between geometry and human society; I am attracted to the aesthetics of dictatorship; I draw inspiration from utilitarian architecture, the design of transport, agricultural, or military machines. Geometry is a language in which society can be described. Normalization is extremely visually interesting for my generation, which attended elementary school during the revolution. The buildings were gray, thus sculpture-like. The visual results of early capitalism, where houses are covered with advertisements, glitter, or styrofoam facades in ice cream colors, must irritate any sensitive aesthetician. We are reaping the fruits of normalization today. In normalization, even the most humble combine harvester had strong aesthetic qualities as it still stemmed from the 60s and the First Republic. Every milk packaging looked like a primitively understood Bauhaus motif. I understand that people who suffered in some way during the regime associate this aesthetic with a period of adversity, but we have the right to view this era from a bird's-eye perspective and say that the work with the visual aspect was interesting and of quality.

However, you refer to the plastics you watch as normalization plastics, which is rather a political designation.

I do not perceive normalization solely in connection with politics; I regard it as a designation of a certain stage. Karel Gott is a pop singer, but he can also be normalization. When someone makes a comic about the heydrichiada, they cannot avoid the swastika, but that does not mean they are a fascist. When I defend a work in the office from destruction, I am usually hit in the face with whether I am a communist. I was born in 1979 and did not even attend the Pioneer. I would like to ask that person in return what they did before 1989. My project is non-political.

In what way is your project artistic?

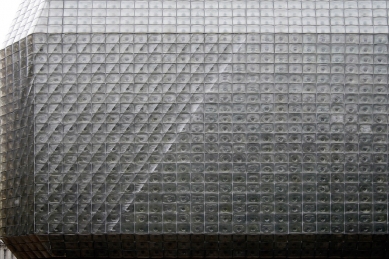

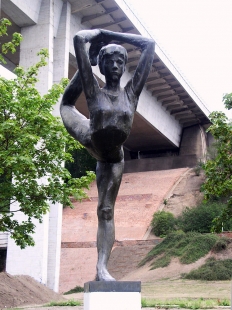

In addition to mapping sculptures, we do projects that we call Strassenkunst. We intervene in sculptures with temporary actions to draw attention to them. For instance, there was an action for the New Stage of the National Theatre, where we temporarily interfered with the sculpture The Birth of Culture by Josef Malejovský from 1982 for about three months. When we photographed the sculpture, the skateboarders who rode around there said to us: “Oh, you are photographing chewing gum?” And indeed, that sculpture looks like chewing gum as if Otto Gutfreund had inhaled toluene for twenty years. So I wrapped the sculpture in pink glue and modeled it into the shape of a giant piece of chewing gum. After all, chewing gum stuck to the sidewalk is also a symbol of public space for me. Or in Folimanka, based on “revitalization,” the plastics of Bohumil Zemánek and Jaroslav Hladký were removed. The municipality was not able to say why this happened and where the sculptures are today, even though millions were spent on revitalization. So we enlarged photos of those sculptures to their original size, glued them on particleboard, and cut out their silhouettes. We then placed these props back at their original locations. Hladký had Prkýnkář from 1982 here, possibly the first skateboard sculpture in the world. It was a very refined piece, a figure with a helmet, pads, and a skateboard; it looked very robotic and futuristic, the base of the sculpture was a U-ramp. Bohumil Zemánek, who made sculptures of fat bureaucrats and was persecuted by the regime for it, here had a humorous group of children who whistle at each other and flirt together. I remember that sculpture as a small child; we climbed on it, and the children had the same proportions as us. It was my first encounter with sculpture, and probably not just for me. I lament that such a sculpture disappears during the revitalization for which there are funds. The remaining sculpture, Gymnast by Václav Frydecký, avoided this madness, so we created, with the author's consent, a protective plexiglass bumper zone for it for three months.

Are you planning to expand your interest outside of Prague, potentially to other periods or other artistic genres?

No, not directly, but any enthusiast who comes across aliens or herons in their town can submit it themselves through a form in our database. We are not the only ones; for instance, some city districts in Prague also monitor sculptures in their territory; Prague 11 has a great database, for example.

Your site is also in English; have you received any feedback from abroad? Do you collaborate with similar projects elsewhere?

Last year, Stephan Strsembski, a curator from Bonn, included me in an exhibition about altruism, where he presented Czech art created out of joy and enthusiasm. Thanks to that, a few people from Germany reached out to me. Americans also contact me because it is something unusual, even strange for them. I regret that I do not have contact with anyone from the former Soviet satellite states. I know that there is a project in Poland that focuses on herons, but it is not solely focused on sculptures.

Are you already functioning as an “institution”? Can anyone turn to you if a sculpture is at risk?

Unintentionally, I am starting to change into an activist, but that is not close to me. I am better at making mischief than officially communicating with authorities. But it’s great that people turn to me. I can help draft a petition, mention it in the media.

What sort of misconduct is happening right now?

There are plenty of such occurrences, for instance, when they removed an eight-meter Brussels relief Nature and Creation by Jaroslav Vacek from the Plamínková Elementary School in Prague 4 in the course of insulating the building by progressively cutting it and dropping it from a height to the ground. As a mockery, they painted a basketball on the façade and claimed it was a full-fledged replacement. Another conceptual removal in Prague 4 occurred at another elementary school, where about a nine-meter relief by Zdeněk Šimek met its demise. It is terrifying to me that the project is signed by an architect who has an education from ČVUT and he doesn’t even understand the quality of execution. I could go on for a long time—removals of Hugo Demartini, Jiří Novák, and Karel Bečvář in the Barrandov housing estate, etc. There are hundreds of such cases in Prague! The justification is often that it is “communist junk,” but then it turns out that the owners are rather lazy to maintain the sculptures and do not bother to find out what kind of sculpture it is. Citizens of Ústí nad Labem are currently fighting for the preservation of the sculpture Labe by Karel Kronych, which stands in front of a department store by Růžena Žertová. The sculpture corresponds with the façade of the building, but the owner of the department store wants to remove it for the sake of garages. Nowadays, there is no money for new realizations; there was back then. The owner does not realize that he is discarding something that will attract tourists in twenty years. Baroque sculptures were also created in a time that is very controversial; according to Jirásek, it was a time of darkness. Those sculptures were ideological tools, symbols of violent re-Catholicization, yet no one doubts that they belong in today's cities.

So, is insulation currently the biggest problem for reliefs?

It is primarily poor revitalization of housing architecture. The culprits are therefore not only thieves of precious metals and hooligans. The main problem is vulgar commercialization of public space, which is facilitated by corruption, and a crucial role is played by insufficient vision in the field of urbanism. Thus, some officials participate in the devaluation of public space hand in hand with vandals.

Don’t some sculptures also end up in the gardens of private individuals?

I hope that is the case, that somewhere at Orlík all those destroyed Malichs, Sýkoras, etc. are. On the other hand, I am afraid that someone might really start speculating with this cultural heritage. But I know for sure that most of the works ended up under jackhammers, often they were not even portable. For example, in Suchdol, there was a monumental five-meter realization by Karel Malich. At a time when his pastels are being bought for hundreds of thousands in private collections, his giant sculpture, which everyone could come and see, is being destroyed.

Shouldn’t the argumentation then change and speak primarily about the financial value of these plastics?

But this is public space, where everything serves everyone; no one has an interest in that...

Pavel Karous (*1979) graduated from the AAAD in Prague, where he currently works as an assistant professor at Rony Plesl's Glass Studio. He initiated the project Aliens and Herons, which aims to document, protect, and popularize sculptures in public space from the 70s and 80s of the 20th century.

More information at www.vetrelciavolavky.cz and www.pavelkarous.cz.

Film by Rozálie Kohoutová (2008) for Czech Television - here.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

10 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

snad mohu pomoci

Jan Sommer

08.08.11 12:07

výborné, ale

Vích

08.08.11 10:22

...Mno,...

šakal

09.08.11 10:07

>> Vích

gallina-scripsit

09.08.11 10:01

fáze

Jiří Schmidt

09.08.11 11:51

show all comments